Eighty years ago, the inaugural Cannes Film Festival was abandoned after a single, unofficial screening. It's now the most glamorous cinema event outside the Oscars and there's only one place for Cinema Paradiso to be and that's on La Croisette.

Publicists and the paparazzi have done their level best to turn Cannes into one big photo opportunity. For all the frolics and scandals that have taken place at the French Riviera resort over the last eight decades, however, the festival manages to turn the media spotlight away from the latest blockbusters for a few days each spring and provides a vital showcase for the best in world cinema.

A Shaky Start

After five years of casting envious glances at the world's first film festival in Venice, the French authorities seized the opportunity to set up a rival event 'to create a spirit of collaboration between all film producing countries' after the Fascists engineered a joint win at the 1938 Mostra for Goffredo Alessandrini's Luciano Serra, Pilot and Leni Riefenstahl's Olympia. Nettled that Jean Renoir's pacifist tract, La Grande Illusion (1937), had been snubbed for Best Foreign Film the previous year, diplomat Philippe Erlanger persuaded Education Minister Jean Zay to support his initiative and Cannes was chosen as host over Biarritz because of the lobbying skills of hotelier Henry Gendre.

With only 10 weeks to curate a programme, the organising committee issued invitations for the major film-producing countries to submit one entry each for the Grand Prix. Few were surprised when Germany and Italy declined to compete, but the United States, Great Britain and the Soviet Union all accepted the invitation, with MGM chartering a liner to send such stars as Gary Cooper, Norma Shearer, Douglas Fairbanks and Tyrone Power to act as Hollywood goodwill ambassadors. Louis Lumière, who had given the first projected cinema show to a paying audience in December 1895, agreed to serve as president of the festival, which was slated to open on 1 September.

However, events elsewhere conspired to spoil the party. The conclusion of the Nazi-Soviet Pact on 23 August cast a shadow over proceedings, while a violent storm brought a premature end to a charity ball on La Croisette, while also soaking the cardboard mock-up that Warner Brothers had erected on the beach to boost the screening of William Dieterle's The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Starring Charles Laughton as Quasimodo, this was the only film shown to the public before the festival was cancelled on 27 August. Five days later, Germany invaded Poland and war duly followed. In 2002, however, it was decided to revisit the abandoned festival and a special jury was convened to award the Palme d'Or to Cecil B. DeMille's Union Pacific, an epic Western starring Barbara Stanwyck and Joel McCrea, in preference to Sam Wood's Goodbye Mr Chips, Jacques Feyder's La Loi du Nord, Mikhail Romm's Lenin in 1918, Zoltan Korda's The Four Feathers, Douglas Sirk's Boefje and Victor Fleming's The Wizard of Oz.

In fact, the Palme d'Or had not been up for grabs in the autumn of 1939 and would only become a permanent fixture at Cannes in 1975. Indeed, when the festival was relaunched on 20 September 1946, it was decided to share the Grand Prix between 10 different films to reflect the new spirit of postwar co-operation. Consequently, Fridrikh Ermler's The Turning Point (USSR), František Cáp's Men Without Wings (Czechoslovakia), Leopold Lindtberg's The Last Chance (Switzerland), Alf Sjöberg's Torment (Sweden), Emilio Fernández's María Candelaria (Mexico), Roberto Rossellini's Rome, Open City (Italy), Chetan Anand's Lowly City (India), Jean Delannoy's La symphonie pastorale (France), David Lean's Brief Encounter (UK), Bodil Ipsen and Lau Lauritzen's The Red Meadows (Denmark), and Billy Wilder's The Lost Weekend (USA) were involved in the biggest tie in festival awards history. Moreover, the latter had the distinction of being the first feature to win the main prize at Cannes and the Academy Award for Best Picture.

Technical difficulties beset the second edition in September 1947, which saw the jury award prizes in different categories rather than select an overall winner. Vincente Minnelli's Ziegfeld Follies won Best Musical Comedy, Jacques Becker's Antoine et Antoinette taking Best Psychological and Love Film, and René Clément's The Damned landing Best Adventure and Crime Film, while Best Animation Design went to Walt Disney's Dumbo and Crossfire, Edward Dmytryk's study of anti-Semitism, took Best Social Film.

But Cannes's future was by no means secure, as a shortage of funds led to the cancellation of the event either side of Carol Reed's classic noir, The Third Man, receiving the Grand Prix in 1949. Two years later, as the festival moved to its now traditional spring slot, Swede Alf Sjöberg became the first director to win the headline award twice, when his adaptation of August Strindberg's Miss Julie tied with Vittorio De Sica's Miracle in Milan (both 1951). The prize was also shared the following year, as the jury couldn't decide between Renato Castellani's Two Pennyworth of Hope and Orson Welles's Othello (both 1952). In 1953, Henri-Georges Clouzot became the first French film-maker to win outright for The Wages of Fear, while Teinosuke Kinugasa became the first Asian winner for Gate of Hell (1954), a masterly example of the jidai-geki genre set in 12th-century Japan.

Cocteau and Silva

The 7th Cannes Film Festival proved to be one of the most important in its history. This was partly due to Egyptian-born, British-based actress Simone Silva celebrating being named Miss Festival by taking off her top to pose for the press on the beach with Hollywood star Robert Mitchum. At once, the sleepy screen event became front page news across the world and starlets have since continued to stage stunts in the hope of earning more than 15 minutes of fame. The other pivotal development at the 1954 event saw jury president Jean Cocteau suggest that the festival adopted a totemic award to match Venice's Golden Lion and the Golden Bear at Berlin. Inspired by Cannes's coat of arms, jeweller Lucienne Lazon came up with a golden palm, which rested on a terracotta pedestal sculpted by the artist Sébastien. It was first presented to Delbert Mann's Marty (1955), which, somewhat remarkably, remains the only film to win both the Palme d'Or and the Oscar for Best Picture.

The first home winners were Yves-Jacques Cousteau and Louis Malle for their pioneering underwater documentary, The Silent World (1956), while William Wyler took the Palme back to Hollywood with Friendly Persuasion (1956), which saw Gary Cooper play a Quaker caught up in the Civil War. The Great Patriotic War provided the setting for Mikhail Kalatozov's The Cranes Are Flying (1957), a textbook example of Socialist Realism that saw lovers Tatiana Samoilova and Alexei Batalov separated when he goes off to fight for Mother Russia.

Doomed love was also the theme of Marcel Camus's Black Orpheus (1959), which reworked the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice against the exotic background of the Rio Carnival. The contrast between the lush colour imagery and the cool monochrome of Federico Fellini's La dolce vita (1960) couldn't have been much greater. But there was another clash of tone the following year, when Henri Colpi's amnesia melodrama, The Long Absence, was deemed the equal of Luis Buñuel's Viridiana (both 1961), which proved a huge embarrassment to Spanish dictator Francisco Franco when he realised that his government had sanctioned a film that openly mocked Roman Catholicism. The Church also came under attack in Anselmo Duarte's The Given Word (1962), which not only became the first Brazilian film to be nominated for an Oscar, but it also remains the country's sole Palme d'Or winner. Its stark monochrome visuals owed much to the neo-realist style refined by Luchino Visconti in Ossessione (1942) and La terra trema (1948). However, he abandoned such austerity in favour of the Technirama opulence he favoured in adapting Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa's epic novel, The Leopard (1963).

However, this turned out to be the last recipient of the Palme d'Or for over a decade, as a copyright dispute prompted the Cannes organisers to reinstate the Grand Prix as their top award. Consequently, masterpieces like Jacques Demy's The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964), Michelangelo Antonioni's Blow-Up (1967), Lindsay Anderson's If... (1969) and Robert Altman's M*A*S*H (1970) were deprived of their Palme moment. But this was hardly a golden age for the Cannes Film Festival, as not only did François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard conspire to sabotage it during the May Days of 1968, but the juries also bestowed the Grand Prix on what many consider to be undeserving titles like Richard Lester's The Knack…and How to Get It (1965), Claude Lelouch's Un homme et une femme, which stared the spoils in 1966 with Pietri Germi's markedly superior commedia all'italiana, The Birds, the Bees and the Italians.

With the honourable exception of compatriots Elio Petri's The Working Class Goes to Heaven and Francesco Rosi's The Mattei Affair, which both starred Gian Maria Volinté and tied in 1972, the last winners of the Grand Prix were a mixed batch, with Francis Ford Coppola's contemporary conspiracy thriller The Conversation (1974) being head and shoulders above a couple of period pieces, Joseph Losey's The Go-Between (1971) and Alan Bridges's The Hireling, which couldn't be separated from Jerry Schatzberg's rather forgotten Al Pacino-Gene Hackman vehicle, Scarecrow, in 1973. But don't take the word of the critics. Make your own judgement by renting the titles available from Cinema Paradiso.

Fronds Reunited

The Palme d'Or was reinstated in time for the 28th edition, which saw Algerian Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina become the first African winner for Chronicle of the Burning Years (1975). But Cannes always seemed to be going through a period of transition, as new attractions were added to the increasingly influential event. The International Critics' Week had become the first festival sidebar in 1962 and it continues to champion the work of film-makers outside the mainstream. As does the Directors' Fortnight, which was introduced in 1969 to provide a new outlet for world cinema. Three years later, Robert Favre Le Bret ended the practice of individual countries submitting pictures for competition by introducing in-house committees which selected titles on their merit. In 1978, new president Gilles Jacob instituted Un Certain Regard to showcase original visions and the Caméra d'Or award for the best first feature.

Over the years, a raft of additional awards have been added, including the Prix du Jury, the Ecumenical Jury Prize, the FIPRESCI Prize, the Prix Vulcan (for technical achievement), the Queer Palm and the Palm Dog, for the best canine performance. On the fringe of the festival, the Hot d'Or gives the porn industry a touch of Cannes glitz, while strands such as Cannes Classics and Tous les Cinémas du Monde have come and gone, along with the various retrospectives and masterclasses that are shown alongside the films screening 'out of competition' away from the Palais des Festivals. For many, Cannes is about Le Marché du Film, an international marketplace for pitching ideas, presenting showreels and cutting deals that was launched in 1959 and was gleefully satirised by James Toback in Seduced and Abandoned (2013), which starred Ryan Gosling and featured cameos by the likes of Bernardo Bertolucci, Roman Polanski, Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese.

The latter had his own moment in the Cannes spotlight in 1976 when Taxi Driver took the Palme d'Or. After Paolo and Vittorio Taviani became the first brothers to triumph with Padre Padrone (1977) and Ermanno Olmi followed up their unflinching depiction of rural Italian life with The Tree of the Wooden Clogs (1978), Coppola would land his second award for Apocalypse Now, which shared the laurels with Volker Schlöndorff's adaptation of Günter Grass's The Tin Drum (both 1979). Ties were all the rage around this period, with the dead heat between Bob Fosse's All That Jazz (1979) and Akira Kurosawa's Kagemusha (1980) being followed by another involving Costa-Gavras's Missing and Serif Gören's Yol (both 1982). This intense Turkish drama was significant because writer-director Yilmaz Güney had smuggled his screenplay out of prison before fleeing to Switzerland with the negative on his release. Martial law had also complicated the shooting of Andrzej Wajda's Man of Iron (1981), which became the first sequel to win the Palme d'Or in following on from the Polish auteur's Man of Marble (1977).

As blockbuster culture seized control of commercial cinema, established festivals like Venice, Cannes and Berlin became beacons of arthouse defiance, while new events like Sundance provided a platform for independent film-makers who struggled to find a niche in mall multiplexes. Steven Soderbergh's Sex, Lies and Videotape (1989) was the first indie to score the top prize at Cannes at the end of a decade when complaints were consistently made about the selections being made by the headline jury. Most were in agreement that Wim Wenders's Paris, Texas (1984) was a worthy winner, but there was markedly less unanimity over Shohei Imamura's The Ballad of Narayama (1983), Emir Kusturica's When Father Was Away on Business (1985), Roland Joffé's The Mission (1986) and Bille August's Pelle the Conqueror (1988), even though the latter also went on to win the Oscar for Best Foreign Film. The most hostile reception, however, was reserved for Maurice Pialat's Under the Sun of Satan (1987), the first French winner for 21 years, which starred Gérard Depardieu as a troubled priest and proved so divisive that the director turned on the jeering audience after receiving his award to retort, 'You don't like me? Well, let me tell you that I don't like you either.'

Chauvinism, Controversy and Complacency

The indie theme continued into the 1990s, with David Lynch's Wild At Heart (1990) and Joel and Ethan Coen's Barton Fink (1991) winning the decade's first two Palmes. Quentin Tarantino added to the number with Pulp Fiction in 1994, but nine years were to pass before another American picture took the title. In the interim, Bille August joined the double-up club with The Best Intentions (1992), which was based on a screenplay by Ingmar Bergman and starred Pernilla August and Samuel Fröler as Bergman's mother and Lutheran pastor father. Two more period pieces took the honours in 1993, as Chinese Fifth Generation director Chen Kaige's Farewell My Concubine was feted alongside Jane Campion's The Piano, which remains the sole Palme d'Or winner to have been directed by a woman. Not that Venice (one), Berlin (three) or the Oscars (one) can put Cannes to shame, as all four showcases have been guilty of chauvinism over the last nine decades.

As cinema marked its centenary in 1995, Emir Kusturica joined the dual winners club with Underground and, two years later, he was followed by Shohei Imamura, whose success with The Eel was shared with Abbas Kiarostami's Taste of Cherry. Sandwiched between these triumphs was Mike Leigh's Secrets & Lies (1996), which gave Britain its first Palme in a quarter of a century.

In order to mark Cannes's 50th anniversary in 1997, a Palme des Palmes was commissioned and presented in absentia to Ingmar Bergman, who had never won the festival's top prize. Curiously, this fate has been shared by the subsequent recipients of the renamed Palme d'honneur between 2002-15, Woody Allen, Manoel De Oliveira, Clint Eastwood, Bernardo Bertolucci and the late, great Agnès Varda. The following year, Greece had its only victory when Theo Angelopoulos's Eternity and a Day became the first recipient of the 24-carat gold Palme that had been redesigned by Caroline Scheufele, while Belgium also debuted with Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne's Rosetta (1999), which they followed up with The Child in 2005.

Yet, while many agreed that the brothers deserved their awards for introducing a new rigour into social realism and reclaiming it from the mire of complacent left-leaning worthiness into which it had slipped, opinion was much more divided on the merits of Dane Lars von Trier's musical melodrama, Dancer in the Dark (2000) and Roman Polanski's The Pianist (2002), even though it earned the controversial Pole the Academy Award for Best Director and the Best Actor statuette for Adrien Brody. Similarly, while Nanni Moretti was commended for his poignant study of bereavement in The Son's Room (2001), debate raged about the quality of Gus Van Sant's high school massacre saga, Elephant (2003), and Michael Moore's Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004), which became only the second documentary to take top prize at Cannes and the first in almost half a century.

Not everyone was convinced that Ken Loach's Irish Civil War drama, The Wind That Shakes the Barley (2006), was amongst his best work, and his tried-and-trusted approach to politicised realism was left looking a little mannered by such hard-hitting offerings as Romanian Cristian Mungiu's 4 Months, 3 Weeks & 2 Days (2007) and Laurent Cantet's The Class (2008), which gave France its first win in 21 years. Five years later, compatriot Abdellatif Kechiche would cause considerable controversy when he won with the graphic lesbian drama, Blue Is the Warmest Colour (2013), which made history when leads Adèle Exarchopoulos and Léa Seydoux were presented with the Palme d'Or along with their director.

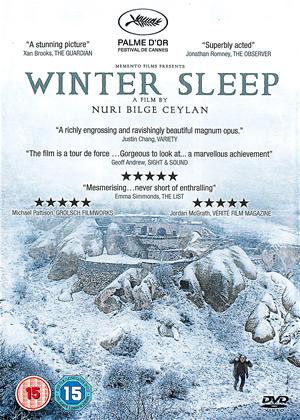

In the interim, Austrian auteur Michael Haneke landed Cannes's quickest double when he won for The White Ribbon (2009) and Amour (2012), and he was joined on the roll of honour in 2016 by Ken Loach, whose I, Daniel Blake (2016) marked a significant return to form in capturing the growing sense of frustration in recessional Britain. Such gritty realism contrasted sharply with the ethereal grace of Thai maestro Apichatpong Weerasethakul's ghost story, Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010), and the philosophical musings of Terrence Malick's poetic essay, The Tree of Life (2011). And, as if to prove there is no such thing as a typical Cannes winner, four of the most recent Palme d'Or winners have been as different as Turk Nuri Bilge Ceylan's journey of self-discovery, Winter Sleep (2014); Jacques Audiard's potent socio-racial integration study, Dheepan (2015); Swede Ruben Östlund caustic art world satire, The Square (2017); and Hirokazu Kore-eda's heartbreaking tale of alternative domesticity, Shoplifters (2018).

As For 2019

Of course, it remains to be seen whose name will join the honours board after the Closing Ceremony on 25 May. Will Ken Loach (Sorry We Missed You) or the Dardennes (Young Ahmed) become the first three-time winners or will Terrence Malick (A Hidden Life) scoop a second Palme d'Or? Will arthouse favourites like Pedro Almódovar (Pain and Glory), Jim Jarmusch (The Dead Don't Die), Ira Sachs (Frankie) and Xavier Dolan (Matthias & Maxime) break their ducks or will Marco Bellocchio (The Traitor) become the oldest first-time winner at the age of 79?

Could Arnaud Desplechin (Oh Mercy!) or Ladj Ly (Les Misérables) provide another home win or will there be a first success for South Korea (Bong Joon-ho's Parasite) or the Palestinian Territories (Elia Suleiman's It Must Be Heaven) ? Could China (Diao Yinan's The Wild Goose Lake), Brazil (Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles's Bacurau) or Romania (Corneliu Porumboiu's The Whistlers) snaffle a second victory? Or, heaven forfend, could this be the year for one of the four women in competition: Austrian Jessica Hausner (Little Joe) or home favourites Justine Triet (Sibyl), Mati Diop (Atlantique) or Céline Sciamma (Portrait of a Lady on Fire) ?

Maybe destiny dictates a sentimental success for the latter after the recent events at Notre Dame? Whatever the outcome, Cinema Paradiso will bring you as many of the aforementioned as possible once they are released on DVD and/or Blu-ray. In the meantime, here are 10 Cannes classics to savour:

-

The White Ribbon (2009) aka: Das Weisse Band

Play trailer2h 17minPlay trailer2h 17min

Play trailer2h 17minPlay trailer2h 17minAlthough there's much to commend Juan José Campanella's Argentinian thriller, The Secret in Their Eyes, it should never have denied Michael Hanke's masterpiece the coveted double of the Palme d'Or and the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film. The Austrian did achieve the feat with Amour (2012), but this immaculate monochrome melodrama set in a North German village on the eve of the Great War is the superior picture, as it exposes the susceptibility of youth to the promptings of their manipulative elders and demonstrates the ease with which fanaticism can take root. The title comes from the tokens that Calvinist pastor Burghart Klaussner forces his adolescent offspring to wear to remind them of their duty to remain pure. But a series of unprovoked assaults generates a mood of malice and menace that's both harrowing and compelling.

- Director:

- Michael Haneke

- Cast:

- Christian Friedel, Ernst Jacobi, Klaus Manchen

- Genre:

- Drama

- Formats:

-

-

4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (2007) aka: 4 luni, 3 saptamâni si 2 zile

Play trailer1h 49minPlay trailer1h 49min

Play trailer1h 49minPlay trailer1h 49minSet in an all-female dormitory in Bucharest during the last days of the Ceausescu regime in the late 1980s, Cristian Mungiu's gruelling study of state chauvinism bristles with provocative ideas and cinematic ingenuity. The dark, daring and devastating drama follows student Anamaria Marinca, as she helps pregnant roommate Laura Vasiliu arrange an illegal appointment with backstreet abortionist Vlad Ivanov. With cinematographer Oleg Mutu adding a rigorous urgency to the sense of oppressive intimacy that he had brought to Cristi Puiu's corrosively bleak The Death of Mr Lazarescu (2005), the mood is one of unremitting realism. But, by confining proceedings to a single night, Mungiu also generates an unbearable tension that peaks as Marinca endures the excruciating ordeal of dining with her boyfriend's family, while Vasiliu is holed up in a hotel room waiting for her 'treatment' to take effect.

- Director:

- Cristian Mungiu

- Cast:

- Anamaria Marinca, Vlad Ivanov, Laura Vasiliu

- Genre:

- Drama

- Formats:

-

-

Taste of Cherry / 10 on Ten (1997) aka: Ta'm e guilass / Dah rooye dah

Play trailer3h 8minPlay trailer3h 8min

Play trailer3h 8minPlay trailer3h 8minThe first Iranian film to win the Palme d'Or, Taste of Cherry shared the accolade with Shohei Imamura's The Eel, which complemented Abbas Kiarostami's story about a man seeking help with his post-suicide burial with its account of a killer hoping to start a new life after being released from prison. The picture only screened at Cannes after Kiarostami's inability to devise a suitable ending and a series of misfortunes during post-production resulted in it missing its Venice deadline. Some were frustrated by the refusal to disclose the reasons for Homayoun Ershadi's malaise, while others delved into the symbolic significance of his conversations with the Kurdish soldier, Afghan seminarian and Turkish taxidermist who try to find reasons for Ershadi to live, as he drives his Range Rover around Tehran and its environs. While challenging, this unique road movie is undeniably thought-provoking.

- Director:

- Abbas Kiarostami

- Cast:

- Homayoun Ershadi, Abdolrahman Bagheri, Afshin Khorshid Bakhtiari

- Genre:

- Action & Adventure, Drama, Documentary

- Formats:

-

-

The Piano (1993)

Play trailer1h 57minPlay trailer1h 57min

Play trailer1h 57minPlay trailer1h 57minForever assured a place in Cannes history as the first Palme d'Or winner to have been directed by a woman, Jane Campion's brooding study of status and the senses, impairment and imperialism, and sounds and silences makes a compelling companion to its co-winner, another intense treatise on sexuality and performance, Chen Kaige's Farewell My Concubine. Seizing upon a role rejected by Sigourney Weaver, Holly Hunter added the Oscar for Best Actress to her Cannes success, as the mute Scottish mail-order bride who arrives in 1850s New Zealand to marry settler Sam Neill with her young daughter, Anna Paquin (who would become the second-youngest Oscar winner), and a baby grand piano that brings Hunter into the orbit of Neill's Maorised forester neighbour, Harvey Keitel. Abetted by Stuart Dryburgh's photography and Michael Nyman's score, Campion gave feminist eroticism literary respectability.

- Director:

- Jane Campion

- Cast:

- Holly Hunter, Harvey Keitel, Sam Neill

- Genre:

- Drama, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

Kagemusha (1980) aka: Kagemusha: The Shadow Warrior

Play trailer2h 32minPlay trailer2h 32min

Play trailer2h 32minPlay trailer2h 32minAlthough Akira Kurosawa is now revered as one of cinema's greatest masters, he was so bruised by his dismissal from 20th Century-Fox's Pearl Harbor epic, Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970), that he attempted suicide. Having only made Dersu Uzala (1975) during the ensuing decade, he was considered a financial risk and it took the intervention of avid fans Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas to enable Kurosawa to make his overdue comeback with this ravishing historical epic based on the life of the 16th-century warlord, Takeda Shingen. The shoot was fraught with difficulties after Kurosawa was forced to replace Zatoichi star Shintaro Katsu with Tatsuya Nakadai after a dispute over on-set cameras. But the combination of exceptional production values, committed playing and Kurosawa's visionary artistry made this chronicle of a 'shadow warrior' as compelling as it was spectacular.

- Director:

- Akira Kurosawa

- Cast:

- Tatsuya Nakadai, Tsutomu Yamazaki, Ken'ichi Hagiwara

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics, Action & Adventure

- Formats:

-

-

The Tree of Wooden Clogs (1978) aka: L'albero degli zoccoli

2h 59min2h 59min

2h 59min2h 59minOriginally produced as a three-part television series, Ermanno Olmi's epic photo-realist memoir of peasant life in late 19th-century Lombardy was hailed as a 'cinematic miracle' by influential American critic Andrew Sarris. Drawing on stories that Olmi's grandmother had told him and filled with props supplied by the non-professional cast to enhance the air of authenticity, the action captures the natural rhythms, grim realities and simple joys of the daily routine on a remote cascina occupied by four families, who rally round in times of crisis and celebration. Speaking in a Bergamesque dialect, the ensemble generates a palpable sense of community, as pigs are slaughtered, tomatoes are planted, babies are delivered and lovers relocate to the big city. But the most fateful task involves a father cutting down a tree to make clogs for his son's arduous walk to school.

- Director:

- Ermanno Olmi

- Cast:

- Luigi Ornaghi, Francesca Moriggi, Omar Brignoli

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

Taxi Driver (1976)

Play trailer1h 49minPlay trailer1h 49min

Play trailer1h 49minPlay trailer1h 49minIt's obvious why the Oscar in America's bicentennial year went to John G. Avildsen's uplifting Rocky rather than Martin Scorsese's dystopic snapshot of a nation reeling from Watergate and Vietnam. However, the Cannes jury recognised the shattering brilliance of Scorsese's evocation of a rundown New York, the unflinching insights of Paul Schrader's Sartrean screenplay and the terrifying intensity of Robert De Niro's performance as Travis Bickle, the dislocated, psychotic war veteran, whose failure to impress political aide Cybill Shepherd during a disastrous date at a porn cinema prompts him to plot the assassination of her boss and the rescue of child prostitute Jodie Foster from her abusive pimp, Harvey Keitel. One of the most memorable moments is Bickle's seething assertion, 'Someday a real rain will come and wash all the scum off the streets.'

- Director:

- Martin Scorsese

- Cast:

- Robert De Niro, Jodie Foster, Cybill Shepherd

- Genre:

- Thrillers, Drama

- Formats:

-

-

The Leopard (1963) aka: Il Gattopardo

Play trailer2h 58minPlay trailer2h 58min

Play trailer2h 58minPlay trailer2h 58minSet in the early 1860s, this impeccably produced treatise on the passing of an era provides a fascinating contrast between the ideas of conservative source novelist Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa and Communist film-maker Luchino Visconti, who was the fourth son of the Duke of Modrone. Having already explored Italian Unification in Senso (1954), Visconti wanted to show how 'Il Risorgimento' created attitudes to class and the past that would shape the nation's future destiny. Cannily, Burt Lancaster based his portrayal of Prince Fabrizio Salina on Visconti, who had resented having the American imposed upon him in order to secure Hollywood funding. But, even though his dialogue was dubbed in the Italian version, Lancaster conveys a sense of wistful pragmatism, as he steers nephew Alain Delon towards a marriage with the nouveau riche Claudia Cardinale.

- Director:

- Luchino Visconti

- Cast:

- Burt Lancaster, Alain Delon, Claudia Cardinale

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

Black Orpheus (1959) aka: Orfeu Negro

Play trailer1h 43minPlay trailer1h 43min

Play trailer1h 43minPlay trailer1h 43minFilmed in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, Marcel Camus's retooling of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice became the first feature to win the Palme d'Or and the Oscar for Best Foreign Film. As Carnival is central to the action, many accused Camus of romanticising the poverty of the hillside shanties in much the same way that 'Brazilian Bombshell' Carmen Miranda had done in Irving Cummings's That Night in Rio (1941). But, while it contributed to the 'tropicalist' backlash that strove to reclaim indigenous culture in the 1960s, the story of a trolley bus driver (footballer Breno Mello) who seeks to keep a country girl (Marpessa Dawn) out of Death's clutches introduced audiences worldwide to an unseen Brazil. Compare cinematographer Jean Bourgoin's shimmering Eastmancolor imagery with the noirish monochrome he employed on Orson Welles's Mr Arkadin (1955).

- Director:

- Marcel Camus

- Cast:

- Breno Mello, Marpessa Dawn, Lourdes de Oliveira

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

Marty (1955)

Play trailer1h 26minPlay trailer1h 26min

Play trailer1h 26minPlay trailer1h 26minA change in the tax law prevented producers Harold Hecht and Burt Lancaster from junking this big-screen version of Paddy Chayefsky's admired teleplay about an Italian-American butcher from the Bronx who defies his overbearing mother and lairy pals to date a mousy teacher. Rod Steiger had played Marty Piletti on TV, but his refusal to sign an exclusive seven-year contract prompted Hecht to cast Ernest Borgnine, who had impressed Lancaster while filming Fred Zinnemann's From Here to Eternity (1953) and Robert Aldrich's Vera Cruz (1954). Bringing a touch of everyday realism to American cinema, director Delbert Mann joined Chayefsky and Borgnine in winning an Oscar for his efforts after the film's success at Cannes had rescued it from the domestic box-office doldrums. Chris Columbus reworked the story as Only the Lonely (1991) for John Candy.

- Director:

- Delbert Mann

- Cast:

- Ernest Borgnine, Betsy Blair, Esther Minciotti

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics, Romance

- Formats:

-