The autumn of 2018 marked the centenary of the founding of Czechoslovakia. With the Czech 100 Festival celebrating the country's cultural achievements over what has been an often tumultuous period, Cinema Paradiso examines the way Czech cinema has reflected and shaped the nation's destiny.

The lands that were merged to form Czechoslovakia were part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire when the first moving pictures were screened at the Casino in Karlovy Vary on 15 July 1896 by an agent of the French Lumière company named Goldschmidt. The novelty entertainment reached Prague in October, which hosted screenings of the first homemade titles two years later. Directed by Jan Krizenecky, Appointment At the Mill, Tears and Laughter and The Billsticker and the Sausage Vendor starred stage comic Josef Svab-Malostransky, who would continue to make films until 1932.

Although the first cinemas relied heavily on imported pictures, entrepreneurs like Antonin Pech, Max Urban and Alois Jalovec formed their own production companies. In 1917, Antonin Fencl's Prazstí Adamité became the first Czech feature film, as it followed the misfortunes of Josef Vošalík in his bid to give his wife the slip and visit the local swimming pool. The first Slovak feature followed four years later, with Jaroslav Siakel's Jánošík chronicling the life of an 18th-century highwayman.

A Time of Exiles

Several stalwarts of Czechoslavakian cinema made their names during the silent era, among them Karel Lamac, Martin Fric and Gustav Machatý, who followed The Kreutzer Sonata (1927) and Erotikon (1929), with Ecstasy (1933), which became a succèss de scandale thanks to the scene in which a young Hedy Kiesler runs naked through the woods. Clips from the film can be seen in Alexandra Dean's documentary, Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story (2017), as Kiesler went on to become a major Hollywood star and a pioneering inventor. She can also be seen in John Cromwell's Algiers (1938) and Jacques Tourneur's Experiment Perilous (1944), which are both available to rent from Cinema Paradiso.

Another Czechoslovak actress to make a name for herself abroad was Anny Ondra, who was disowned by her family after she moved in with Lamac while still a teenager. She is best known for two collaborations with Alfred Hitchcock, The Manxman and Blackmail (both 1929), although her accent was so thick that her lines were dubbed in the latter by Joan Barry. In 1933, Ondra married German boxing champion Max Schmeling and spent the next 12 year resisting the efforts of the Nazi hierarchy to make them the Third Reich's golden couple.

Despite the sophistication of silents like Premysl Pražský's Battalion (1927) and Jan Kolár's St Wenceslas (1930), sound came with Karel Anton's Tonka of the Gallows (1930), although it still made extensive use of intertitles. Starring Ita Rina, the story resembles FW Murnau's Sunrise (1927) with its contrast between town and country living. Among the first genuine talkies was Lamac's Imperial and Royal Field Marshal (1930), which confirmed the star status of ex-Sparta Prague goalkeeper, Vlasta Burian, whose comedies remain popular today, even though he was denounced for his supposed wartime collaboration when he was actually mocking all things German.

Language restrictions meant that few Czechoslovakian films were seen outside Central Europe. Nevertheless, several familiar names emerged between the wars, including Svatopluk Innemann, whose enduring popular comedy, Muži v offsidu (1931), starred actor-director Hugo Haas, who directed himself in a 1937 adaptation of Karel Capek's anti-fascist play, The White Disease. Driven into exile, Haas made numerous Hollywood pictures include Douglas Sirk's Summer Storm, Jacques Tourneur's Days of Glory (both 1944) and John Berry's Casbah (1948).

Frequent collaborators Jan Werich and Jirí Voskovec similarly advocated political freedom in Jindrich Honzl's Your Money or Your Life (1932) and Martin Fric's The World Belongs to Us (1937). Consequently, they also wound up Stateside, with the newly named George Voskovec memorably playing Juror #11 in Sidney Lumet's 12 Angry Men (1957). Werich missed his chance of immortality, however, as he was fired from the role of Ernst Stavro Blofield in the 1967 James Bond adventure, You Only Live Twice, for being less like a supervillain and more like 'a poor, benevolent Santa Claus'.

Ingenuity led Alfréd Radok to develop the Laterna Magika, a multimedia spectacle that combined projected images with live-action drama and dance. With a set designer Josef Svoboda and a young Miloš Forman among his assistants, Radok won the gold medal at the 1958 Brussels EXPO and the National Theatre in Prague continues to host productions using the latest variations on the apparatus. Czech technology was also behind Radúz Cincera's Kinoautomat, which was billed as 'the first interactive film in the world' when it was unveiled at Montreal's EXPO '67. In addition to playing the lead on screen, Miroslav Hornícek also served as an emcee in the purpose-built auditorium, whose 127 seats were fitted with red and green buttons that allowed the audience to vote on the action beamed from two synchronised projectors.

Vávra and Weiss

Another major figure in Czech cinema at this time was Otakar Vávra, the prolific director who made several films with Zorka Janú and her sister, Lida Baarová, who earned notoriety by becoming the mistress of Nazi propaganda chief, Josef Goebbels. She would later appear in Federico Fellini's I Vitelloni (1953), while her career in Germany comes under scrutiny in Rüdiger Suchsland's magnificent documentary, Hitler's Hollywood (2017), which reveals how directors were encouraged to use stock situations and stereotypes in the 1000 films produced between 1933-45 to reinforce the tenets of Nazi ideology.

Vávra is considered by many to be the father of Czech cinema and he is best known for the Hussite trilogy that is comprised of Jan Hus (1954), Jan Žižka (1955) and Against All Odds (1957). However, he returned to the theme of religious intolerance in Witchhammer (1970), one of many Czech films available from Second Run. An allegorical study of totalitarian oppression, this account of a pitiless 17th-century witchcraft trial that contains echoes of Carl Theodor Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) and Jerzy Kawalerowicz's Mother Joan of the Angels (1961), while also anticipating many of the themes in Ken Russell's The Devils (1971).

While Vávra remained at the state-of-the-art Barrandov Studios in Prague and adapted to life under Nazism and Communism alike, the likes of director Jiri Weiss and cinematographer Otto Heller fled abroad. They found sanctuary in Britain, where Weiss made the propaganda short, Before the Raid (1943), in which some Norwegian sailors tell their British counterparts about life under the jackboot in their fishing village. In 1960, Weiss returned home to make Romeo, Juliet and Darkness, in which Ivan Mistrík shelters Jewish fugitive Daniela Smutná in his Prague attic during the Nazi round-ups of 1942.

Weiss renewed his links with Britain in filming Ninety Degrees in the Shade (1965) on a Prague soundstage. Nominated for a Golden Globe, this claustrophobic insight into life under constant surveillance centres on the arrival of government inspector Rudolf Hrušínský at the off-licence managed by Anne Heywood, where shifty employee James Booth has been syphoning off the stock to sell on the black market. Booth had starred with Michael Caine in Cy Endfield's Zulu (1964) and Caine worked on three notable occasions with Otto Heller, on Sidney J. Furie's The Ipcress File (1965), Lewis Gilbert's Alfie and Guy Hamilton's Funeral in Berlin (both 1966).

Master Animators

In 1947, the Czechoslovakian film industry was nationalised. The same year also saw the famous FAMU film school open its doors, while Karel Stekly's The Strike won the Golden Lion at Venice. Animator Jirí Trnka also made his name with The Czech Year and the 'Walt Disney of Eastern Europe' would inspire such talents as Karel Zeman, Jirí Brdecka, Bretislav Pojar and Jan Švankmajer with magical (and slyly satirical) puppet films.

Zeman and Švankmajer were noted for combining live-action and animated footage in their endlessly inventive fantasies, which always contained a degree of cutting satire. Bearing the influence of the French pioneer, Georges Méliès, Invention for Destruction (1958) follows the efforts of a professor and his assistant to elude some pirates and became an international success under the title The Fabulous World of Jules Verne. Zeman showed a similar gift for storytelling spectacle in The Fabulous Baron Munchausen (1961) and A Jester's Tale (1964), a paean to the common people that draws on the work of 17th-century Swiss engraver Matthäus Merian in combining swashbuckling and slapstick. Among those taking their cues from Zeman was Jindrich Polák, who anticipated many Hollywood sci-fi tropes in adapting Stanislaw Lem's novel, Ikarie XB 1 (1963), which is also known as Voyage to the End of the Universe.

By contrast, Švankmajer specialised in surreal shorts whose philosophical depth, visual ingenuity and satirical acuity led to several brushes with the censors. Early outings like A Quiet Week in the House (1969) and Leonardo's Diary (1972), as well as such later classics as Dimensions of Dialogue (1982) and Down to the Cellar (1983) had a profound influence on animators like Terry Gilliam and the Brothers Quay and can be found on the BFI's Jan Švankmajer: The Complete Short Films. But Švankmajer was able to indulge his passion for an unsettling image and acerbic aside in such distinctive features as Alice (1988), Conspirators of Pleasure (1996), Lunacy (2005) and Surviving Life (2010), which exploit stop-motion techniques and eschew computerised effects to make their often grotesque characters seem out of place in their everyday environments.

Circumventing Socialist Realism

Following the Communist coup in February 1948, Czechoslovakia became a very different place and film-makers were required to present Party-approved snapshots of everyday life using a style known as Socialist Realism. Strict censorship was imposed in 1959 and a number of directors began making films about the Second World War as a way of commenting on the contemporary scene while seeming to denounce fascism and celebrate the stoicism of the Czech people.

Two of the best-known examples are Jan Kadár and Elmas Klos's The Shop on the High Street (1965) and Jirí Menzel's Closely Observed Trains (1966), which won the Oscar for Best Foreign Film in successive years. These appear in our Top 10 below. But Zbynek Brynych's Transport From Paradise (1963) is equally potent, as it recreates the moment in June 1944 when a Red Cross party visited the model ghetto at Terezin. The incident had been filmed by Kurt Gerron, who had appeared alongside Marlene Dietrich in Josef von Sternberg's The Blue Angel (1930), and it is revisited by Claude Lanzmann in his harrowing 2013 documentary, The Last of the Unjust, which profiles Rabbi Benjamin Murmelstein, who was the last surviving leader of the Theresienstadt Jewish Council.

Brynych's masterpiece was scripted by Shoah survivor Arnošt Lustig, who also wrote Jan Nemec's Diamonds of the Night (1964). Set over four days and running just 63 excruciating minutes, the action follows Jewish boys Ladislav Jánsky and Antonin Kumbera, as they cross hostile terrain after escaping from a train bound for a concentration camp. Virtually eschewing dialogue and making audacious use of handheld point-of-view shots, flashbacks, dreams and recollections, this conveys the terror of the Holocaust more vividly and graphically than any overblown Hollywood epic.

Having started out in puppet and military films, František Vlácil happened upon another way of bypassing the censor using allegorical formalism. This manifested itself in a mix of neo-realism and enchanted expressionism in his debut feature, The White Dove (1960), which sees a wheelchair-bound boy learn to take responsibility for his actions after shooting at a homing pigeon with his air rifle. Taking a leaf from Albert Lamorisse's White Mane (1953) and The Red Balloon (1956), Vlácil avoids cheap sentiment and his refusal to follow the rules is even more readily apparent in Markéta Lazarová (1967), which was declared the finest achievement in Czech screen history in 1998.

He followed it with another visually striking and thematically contentious medieval saga, The Valley of the Bees (1968), a treatise on orthodoxy and the price of independent thought that contains echoes of Ingmar Bergman, Robert Bresson, Luis Buñuel and Andrei Tarkovsky. As its release coincided with the curtailment of the Prague Spring, however, it was rapidly suppressed and Vlácil was banned from making films for seven years after he offended the authorities with Adelheid (1969). Adapted from a novel by Vladimír Körner, the story of a returning war hero dispatched to compile an inventory of the mansion owned by a suspected collaborator reflected the mood of moral and political uncertainty following the Soviet incursion.

The Czech New Wave

Although Czechoslovakian film-makers had been quietly subverting Socialist Realism since its inception, they were also given plenty of encouragement by exiles like Karel Reisz, who had been one of the 669 Czech children saved by Nicholas Winton in March 1939. Their story is told in Matej Minac's Nicky's Family (2011), but Reisz and Tony Richardson took a bolder approach to actuality in Momma Don't Allow (1955), a record of a night at a North London jazz club that was included in the first programme of Free Cinema shorts shown at the National Film Theatre. Several of these hugely influential films can be seen on the BFI collection, Free Cinema (1952-63), while Cinema Paradiso also gives users the chance to see such other Reisz offerings as We Are the Lambeth Boys (1959), Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960), Morgan: A Suitable Case for Treatment (1966), Isadora (1968), Dog Soldiers (1978), The French Lieutenant's Woman (1981), Sweet Dreams (1985) and Everybody Wins (1990).

Although the imprint of the nouvelle vague and the Second Italian Film Renaissance is readily evident, Miloš Forman also acknowledged the influence of Free Cinema and British social realism on his breakthrough films. But the first inkling of the Czech new wave is usually considered to be The Sun in a Net (1962), a highly stylised and technically bold view of modern life by Štefan Uher, a Slovak who would continue to work steadily alongside compatriots like Eduard Grecner, who used medieval folklore and superstition to critique life under stricture in Dragon's Return (1967).

Much of the impetus, however, came from Vera Chytilová, a former model who had trained at the FAMU film school, where she combined the avant-garde and cinéma vérité to assess the status of women in Czech society in the short, A Bag of Fleas (1962). Following her shrewd comparison of the lives of a housewife and an Olympic gymnast in Something Different (1963), Chytilová made Daisies (1966), a gleeful satire about two girls on a self-indulgent and, ultimately, self-destructive binge, and Fruit of Paradise (1969), an updating of the Adam and Eve story that so infuriated the authorities with its nihilism that Chytilová was forbidden from making films for several years.

She would resume her career with The Apple Game (1975) and continued to produce pictures like Traps (1998) after the Velvet Revolution of 1989. But, while she struggled for recognition alongside fellow outlaws Jan Schmidt and Pavel Juracek (Josef Kilián, 1963), and Jan Nemec (The Party and the Guests, 1966), their FAMU classmate, Miloš Forman, became one of the most lauded film-makers in the world. Breaching the conventions of traditional narrative and reconstructing reality through the acute observation of minor details and character traits, Forman followed his debut, Audition (1963), by mocking the government's network of informers in Black Peter (1963), the army and the banality of daily life in A Blonde in Love (1965) and human vanity, folly, greed and envy in The Fireman's Ball (1967).

However, he was fired by his studio while negotiating a deal for his first American feature and decided to make Hollywood his home. He began confidently with the counterculture trilogy of Taking Off (1971), One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975) and Hair (1978). His adaptation of Ken Kesey's novel about an asylum became the first film since Frank Capra's It Happened One Night (1934) to win the Big Five Oscars. But, while Forman missed his step in bringing James Cagney out of retirement for Ragtime (1981), he bounced back triumphantly with Amadeus (1984), which also won the Oscars for Best Picture and Best Director.

Forman struggled to recapture past glories with later projects like Valmont (1989), The People vs Larry Flynt (1996), Man on the Moon (1999) and Goya's Ghosts (2006). But he remains the New Wave's most familiar name and he exerted a considerable influence on former assistant Ivan Passer, who peaked with his debut feature, Intimate Lightning (1965). However, he still produced several interesting films Stateside, including Born to Win (1971), Silver Bears (1977), the excellent Cutter's Way (1981) and Creator (1985).

Miloš Forman's most fervent disciple, however, was Jirí Menzel, whose Oscar victory didn't protect him from official opprobrium after he dissected the sexual misadventures of three middle-aged friends in Capricious Summer (1968) and followed the fortunes of three strangers undergoing political rehabilitation in a junkyard in Larks on a String (1969). Rebuilding his career after a prolonged ban, Menzel remains active, with the microcosmic comedy I Served the King of England (2006) being his sixth collaboration with novelist Bohumil Hrabal, who also provided material for Chytilová, Passer, Nemec, Schorm, Jaromil Jireš and Juraj Herz.

Despite being censured for his nouvelle vague-influenced satire, Jireš remained in Czechoslovakia and continued with Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (1969), a left-field fantasy in which a teenage girl discovers through a pair of enchanted earrings that her provincial town is full of witches and vampires. Jireš's cult classic shares a strain of surrealist horror with Juraj Herz's The Cremator (1968) and Morgiana (1972). The former features an exceptional performance by Rudolf Hrušínský, as the inter-war crematorium worker whose obsession with liberating souls tips him over the edge as Nazi tanks threaten to invade, while the latter boasts an equally remarkable turn by Iva Janžurová, who plays 19th-century sisters trapped in a dispute over their father's inheritance and the man they both love.

Magda Vášáryová finds herself in another ménage in Juraj Jakubisko's Birds, Orphans and Fools (1969), as she strives to find the good in life while dwelling in a bombed-out church at the end of a pitiless war. Made shortly after the crushing of the Prague Spring and bearing the influence of Luis Buñuel and Jean-Luc Godard, this mesmerising morality tale proved too provocative for the new regime and it was shelved until after the Velvet Revolution. Subsequently, Jakubisko has continued to rattle cages with pictures as different as Post Coitum (2004) and Bathory: Countess of Blood (2008). But Vojtech Jasný wisely opted for exile after he followed his mischievous fantasy, Cassandra Cat (1963), with All My Good Countrymen (1968), a foundation saga that was 'banned forever' for its depiction of Czechoslovakia after the coming of Communism; Czech cinema was cast into doldrums from which it would not emerge as a global force for two decades.

The Velvet Touch

Although many new wavers were eventually allowed to return to the fold, the quality of Czechoslovakian cinema dipped from the 1970s, despite the best efforts of Dušan Hanák (Pictures of the Old World, 1972), Oldrich Lipský, children's film-maker Véra Plívová-Simková, animator Jirí Barta, the comedy duo of Zdenek Sverák and Ladislav Smoljak and Karel Smyczek. The latter chimed in with other social protest pictures like Milos Zábransky's A House for Two (1988) and Petr Koliha's Tender Barbarians (1989), which helped prepare the ground for the Velvet Revolution.

Numerous 'vault films' were dusted down and screened for the first time since the Prague Spring, while the new era's first feature was Were We Really Like This? (1990), which was directed by Antonin Mása, who was returning to cinema after a prolonged exile in the theatre. But, without the state subsidies that had bolstered it during the Communist era, the film industry soon plunged into a crisis, with only 14 pictures being made in the Czech Republic in 1993, while Slovakian cinema could only average between two and four films a year.

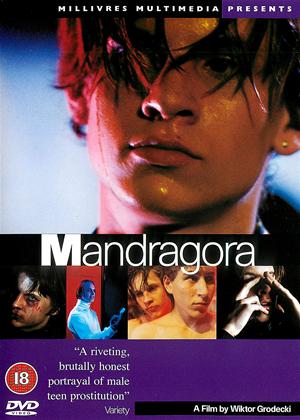

However, Wiktor Grodecki became the country's first director to focus on gay characters in Not Angels But Angels (1994), Body Without Soul (1996) and Mandragora (1997), while a generation of newcomers emerged that included Irena Pavlásková, Zdenec Tyc, Alice Nellis, Vladimír Michálek, Milan Cieslar (Spring of Life, 2000 & Prisoners of Auschwitz, 2013), Tomáš Hejtmánek, Václav Marhoul (1941: The Battle of Tobruk, 2008), Petr Nikolaev and Petr Václav.

The proud Czech traditions for animation and children's films have been continued by the likes of Juraj Lehotsky (Blind Loves, 2008) and Tomás Lunák (Alois Nebel, 2011) and Galina Miklínová (Oddsockeaters, 2016). FAMU also retains its importance, with alumnus Jan Hrebejk having produced such admired features as Divided We Fall (2000) and Pupendo (2003), the middle one of which is a black comedy based on real events during the Second World War, which was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film.

The best-known current Czech director is Jan Sverák, who has frequently collaborated with his actor-writer father, Zdenek Sverák. Sverák won the Best Foreign Film award with Kolya (1996), he has since commemorated the achievements of the Czechs who flew with the RAF during the Battle of Britain in Dark Blue World (2001) and exposed the failure of free-market democracy to solve the Czech Republic's problems in Empties (2007).

-

Kolya (1996) aka: Kolja

1h 41min1h 41min

1h 41min1h 41minThe father-son team of Zdenek and Jan Sverák earned the Czech Republic its first Oscar with this bittersweet treatise on political transition. Set two decades after the Prague Spring and the year before the Velvet Revolution, the scenario is replete with meaningful undertones. But the Sveráks are content to raise the spectres and allow the focus to fall on the odd couple bond that forms between a fiftysomething cellist and the five year-old son of the runaway Russian woman he married in order to pay off his debts after he is laid off by the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra and has to start playing at funerals. Despite not sharing a common language, the byplay between Sverák Senior and Andrej Chalimon is as enchanting as Vladimír Smutný's photography is exquisite.

- Director:

- Jan Sverák

- Cast:

- Zdenek Sverák, Andrei Chalimon, Libuse Safránková

- Genre:

- Comedy

- Formats:

-

-

The Ear (1970) aka: Ucho

1h 31min1h 31min

1h 31min1h 31minScripted by longtime collaborator Jan Procházka, Karel Kachyna's classic dissection of apparatchik paranoia contains traces of both Mike Nichols's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and Jan Nemec's The Party and the Guests (both 1966). Arriving home to wife Jirina Bohdalová, minor government official Radoslav Brzobohatý keeps thinking back to the Party reception at which his boss was denounced. Convinced he is next for the chop because the power and phone have been cut off, Brzobohatý is berating his increasingly tipsy wife when they are interrupted by a deputation of guests from the soirée. Ending chillingly with a surprise revelation and a desperate search for bugging devices, this is a brilliantly controlled blend of domestic melodrama and political satire that is played with compelling power by its magnetic leads.

- Director:

- Karel Kachyna

- Cast:

- Jirina Bohdalová, Radoslav Brzobohatý, Gustav Opocenský

- Genre:

- Comedy, Classics, Drama

- Formats:

-

-

Marketa Lazarova (1967)

2h 39min2h 39min

2h 39min2h 39minAdapted from a 1931 novel by Vladislav Vancura, František Vlácil's masterpiece is an intricate, intense and often savage saga that bears comparison with the period pictures of Orson Welles, Ingmar Bergman and Akira Kurosawa. Set in 13th-century Bohemia, the action turns around two feuding clans and the consequences for aspiring nun Magda Vásáryová when a royal emissary is dispatched to bring the rivals to heel after they ambush a prominent bishop. Dividing the story into two parts and refusing to reveal the outcome of the climactic forest showdown, Vlácil makes the audience work to follow the various flashbacks, dream sequences and quasi-ecstatic hallucinations. But the Bruegelesque visuals and unflinching depiction of the bestial brutality required to survive these gruesome times ensure that this grips like Game of Thrones.

- Director:

- František Vlácil

- Cast:

- Josef Kemr, Antonie Hegerlíková, Magda Vásáryová

- Genre:

- Drama

- Formats:

-

-

The Fireman's Ball (1967) aka: Horí, má panenko

1h 10min1h 10min

1h 10min1h 10minMiloš Forman's parting shot to his homeland begins as a gently parodic satire on small-town manners. But it slowly builds into a scathing allegorical denunciation of the incompetence, insularity and ideological idiocy of the ruling regime. At the centre of events is retiring fire chief Jan Stöckl, whose farewell party descends into chaos when beauty contestants refuse to parade and the raffle prizes are stolen. To cap things off, the firemen get so blotto that they are unable to prevent a house from burning down. Such is the emphasis on the farce that this lacks the finesse of A Blonde in Love (1965), But the gags keep coming and it's easy to forget that this Socialist Realist romp is lampooning the Stalinist purges. No wonder it was 'banned forever'.

- Director:

- Milos Forman

- Cast:

- Jan Vostrcil, Josef Sebánek, Josef Valnoha

- Genre:

- Comedy, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

Daisies (1966) aka: Sedmikrásky

Play trailer1h 13minPlay trailer1h 13min

Play trailer1h 13minPlay trailer1h 13minThe Film Miracle's two most significant female artists collaborated on this anarchic assault on materialism. In addition to designing the stylised visuals, Ester Krumbachova also co-wrote the screenplay with director Vera Chytilova, whose husband, Jaroslav Kucera, served as cinematographer. Employing collage, superimposition, symbolic mise-en-scène, prismatic distortion and nudity, the trio concocted a Surrealist fantasy of the banality and conformity of Czechoslovakian society, as two girls named Marie dupe several boorish males before indulging in an orgy of gleeful destruction. This may shriek Swinging Sixties from almost every frame. But the energy and kittenish mischief of Ivana Karbanová and Jitka Cerhová remain undiminished and it's still easy to be swept along by the surfeit of brilliant ideas and the pace and panache with which they are executed.

- Director:

- Vera Chytilová

- Cast:

- Jitka Cerhová, Marie Cesková, Ivana Karbanová

- Genre:

- Comedy, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

The Party and the Guests (1966) aka: O slavnosti a hostech / A Report on the Party and Guests

1h 8min1h 8min

1h 8min1h 8minA Kafkaesque pall pervades this provocative study of the paranoia permeating every stratum of Czechoslovakian society during the Communist era. Jan Nemec and writer/designer wife, Ester Krumbachova, set their tale in the Edenic woodlands that are being enjoyed by seven picnickers before they are waylaid, first by the menacing Jan Klusák and his thugs and then by the white-jacketed Ivan Vyskocil, whose urbanity vanishes when one of the guests absconds from his birthday party. This sinister study of social conformity and political dissent follows the increasingly hysterical pursuit of the last-remaining, self-determining individualist, whose refusal to acquiesce in the system threatens the status quo. Ironically, he is played by director Evald Schorm, who would be similarly harried over his banned feature, Return of the Prodigal Son (1967).

- Director:

- Jan Nemec

- Cast:

- Ivan Vyskocil, Jan Klusák, Jiri Nemec

- Genre:

- Comedy, Drama, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

Closely Observed Trains (1966) aka: Ostre sledované vlaky

Play trailer1h 28minPlay trailer1h 28min

Play trailer1h 28minPlay trailer1h 28minEarning Czechoslovakia back-to-back Oscars, the debuting Jirí Menzel's adaptation of Bohumil Hrabal's acclaimed novel about sabotage at a provincial railway station during the Nazi Occupation was turned down by both Evald Schorm and Vera Chytilová. But Menzel invokes the spirit of Jaroslav Hasek's seminal pacifist tract, The Good Soldier Schweik, to debunk the notions of heroism central to Czech war movies. Hailing from generations of bungling nobodies, Václav Neckár is more interested in losing his virginity than defeating the Germans who have invaded his backwater town. Thus, lust rather than patriotism prompts his decision to accept a perilous mission from partisan Nada Urbankova. The ensemble playing is as impeccable as the period setting. But it's Menzel's irrepressible sense of subversive mischief that makes this so audacious, amusing and affecting.

- Director:

- Jirí Menzel

- Cast:

- Václav Neckár, Josef Somr, Vlastimil Brodský

- Genre:

- Classics, Drama, Comedy

- Formats:

-

-

The Shop on the High Street (1965) aka: Obchod na korze

2h 0min2h 0min

2h 0min2h 0minAlthough they are associated with the Czech New Wave, Jan Kadár and Elmar Klos were veteran film-makers who had frequently riled the censors with experiments in poetic realism, stylised fantasy and wartime melodrama. But the story of carpenter Jozef Kroner's relationship with Jewish widow Ida Kaminska after he is made Aryan controller of her sewing shop had a deceptive human-level simplicity that allowed international audiences to engage with its themes of trust, morality and community without necessarily appreciating its allegorical potency. This is perhaps why it won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film, as Kroner's efforts to protect Kaminska from the increasingly brutal realities of the Holocaust are both bleakly hilarious and heart-wrenchingly tragic.

- Director:

- Ján Kadár

- Cast:

- Ida Kaminska, Jozef Króner, Hana Slivková

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

Intimate Lighting (1965) aka: Intimni Osvetleni

1h 12min1h 12min

1h 12min1h 12minIn Ivan Passer's debut, Communist Czechoslovakia is compared to a provincial orchestra that tries hard, but couldn't play Dvorák if its life depended upon it. However, music teacher Karel Blazek is determined to whip his charges into shape, as best friend Zdenek Bezusek is due to visit with his trendy Prague girlfriend, Vera Kresadlová, and the ultra-competitive Blazek wants to put on a good show. The banter between the trumpeter and his cellist guest is forever being disrupted by quotidian inconsequentialities and Passer's lightness of touch means that the sheer mundanity of the action leaves one smiling while seeking underlying meanings. Kresadlová (who was married to Miloš Forman) is splendidly coquettish, while Bezusek's performance is all the more affecting because he was suffering from terminal leukaemia.

- Director:

- Ivan Passer

- Cast:

- Zdenek Bezusek, Karel Blazek, Miroslav Cvrk

- Genre:

- Classics, Drama, Comedy

- Formats:

-

-

The Sun in a Net (1962) aka: Slnko v sieti

1h 30min1h 30min

1h 30min1h 30minAdapted by Alfonz Bednár from three of his own short stories, Štefan Uher's sophomore feature is a beguiling rite of passage. By repeatedly obscuring the view of Stanislav Szomolányi's camera and having composer Ilja Zeljenka and sound designer Rudolf Pavlicek fill the soundtrack with conflicting and discordant noises, Uher conveys the difficulty that Bratislava student and amateur photographer Marián Bielik has in understanding the world around him. There are echoes of Ingmar Bergman's Summer With Monika (1952) in Bielik's country camp encounter with Olga Šalagová, whose wholesome willingness contrasts with the domestic woes of city teenager Jana Beláková. But, while the Slovakian authorities complained about the symbolic use of eclipses and parched riverbeds, Uher slipped in much more veiled criticism that they failed to detect.

- Director:

- Stefan Uher

- Cast:

- Marián Bielik, Jana Beláková, Olga Salagová

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics

- Formats:

-