At 11 am on Sunday 3 September 1939, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain took to the airwaves from the Cabinet Room at 10 Downing Street. He solemnly announced that Germany had ignored British demands for a withdrawal of its troops from Poland and that a state of war now existed between the two countries. Less than 21 years had passed since the signing of the Armistice to end all wars. In order to mark the 80th anniversary of the outbreak of the Second World War, Cinema Paradiso looks at the British films about life on the Home Front and in Occupied Europe that have been made since that sunny autumn morning when a nation and its people changed forever.

It was called 'The People's War', as everyone was in the fight against Nazi Germany together. From the outset, civilians in the bigger cities knew that this would be a war unlike any other because they would be the target of aerial bombardment from the Luftwaffe. But, as Humphrey Jennings reported in the 1940 documentary, The First Days, the expected assault didn't come. Indeed, Europe entered a phase of the Phoney War, as the leaders of the Allies and the Axis took stock of their situations and put their armaments industries into overdrive. The British government also began preparing for a propaganda war, with the Ministry of Information being set up to keep the public aware of developments abroad and the duties that would be expected of them at home in order that every man, woman and child could do their bit for the war effort.

Keeping the Home Fires Burning

Only three British film studios remained in operation throughout the Second World War. While avoiding the Great War mistake of silencing cinema, the MOI was faced with the difficulty of enlightening and entertaining viewers of very different ages, tastes and social backgrounds on severely reduced budgets. while also being prevented from discussing certain topics for fear of giving away national secrets or having a negative impact on morale. Perhaps that's why the best-known film about the Home Front was made in Hollywood. Based on Jan Struther's newspaper column, William Wyler's Mrs Miniver (1942) was set in the fictional Kent village of Belham and starred Greer Garson and Walter Pidgeon as the plucky couple facing up to the threat of invasion. Despite being mauled by British critics for being insultingly sentimental, MGM's melodrama won six Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Actress, and gave US audiences an idea of what their transatlantic counterparts were enduring.

Homegrown film-makers knew that the British public wouldn't stand for such a romanticised fantasy and plumped instead for a blend of escapism and everyday realism that gave wartime dramas, thrillers and comedies alike a sense of authentic optimism. While the enemy was sometimes caricatured, it was mostly taken seriously in being shown as ruthless and cunning. But the Nazis and their detestable cohorts in the countries they occupied were never presented as invincible, just as British characters were never depicted as paragons of virtue who were too good to be true. In order to be effective, fictional wartime pictures had to tell it like it was and leave the overt propagandising to the kind of MOI short that can be found on such excellent collections as Home Front Britain, the BFI's Ration Books and Rabbit Pies: Films From the Home Front, and such Imperial War Museum anthologies as Women and Children At War, The British Home Front At War, Britain's Home Front At War: London Can Take It, The Home Guard and Britain's Citizen Army, and Words For Battle: Writers At War.

Not every film produced in Britain between 1939-45 dealt with the war, as audiences needed a break from the all-consuming business of keeping calm and carrying on. But we shall concentrate on those titles that focused on the conflict and the events that led up to it. A clutch of pictures, for example, reflected on the policy of appeasement that has been practised during the 1930s by the Conservative governments of Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain. Maurice Elvey and Castleton Knight's For Freedom (1940) centres on newsreel chief Will Fyffe, who warns against the Nazi threat after the 1938 Munich Agreement and continues to campaign against Hitler until the Graf Spee is sunk in Montevideo Harbour. However, having failed to alert people of the need to stand up to Hitler's bullying tactics, journalist Michael Redgrave turns his back on the world in Roy Boulting's Thunder Rock (1940) and becomes the keeper of a remote lighthouse on Lake Michigan. However, his conscience continues to trouble him.

One of the first policies to be implemented after the war was declared was the evacuation of children from Britain's major urban areas. Maclean Rogers put a comic spin on what proved traumatic for parents and children alike in Gert and Daisy's Weekend and Front Line Kids. The former sees Elsie and Doris Waters take some evacuees to the country, where they catch some jewel thieves in a stately home, while the latter recycles the plot to allow porter Leslie Fuller to nab a gang in a London hotel with the help of some unruly kids who stubbornly refuse to leave the capital.

These films were made in 1942, the year in which Evelyn Waugh published the best wartime novel about evacuees. Sadly, the BBC adaptation of Put Out More Flags hasn't been seen since it was broadcast in 1970. But it is possible to watch Jack Gold's take on Michelle Magorian's Goodnight Mr Tom (1981), which stars John Thaw as Tom Oakley, an embittered widowed recluse living in the village of Little Weirwold, who is ordered to take in troubled nine year-old William Beech (Nick Robinson) after he is evacuated from Deptford in September 1939.

Quite a number of wartime flag-wavers contained the leading comedy stars of the day, as the MOI realised that people were more likely to respond to messages about rationing, making do and mending and careless talk costing lives if they were slipped into lighthearted scenarios rather than stressed in weightier dramas. Consequently, the likes of Lancastrian Frank Randle were encouraged to act the goat in service comedies like John E. Blakeney's Somewhere in Camp and Somewhere on Leave (both 1942), in which Randle and his fellow conscripts respectively help a buddy romance their commanding officer's daughter and cause mayhem when they are invited to stay with a well-heeled comrade in arms. Radio star Arthur Askey also joins up in Marcel Varnel's King Arthur Was a Gentleman (1942), only to become convinced that he's invincible after being tricked into believing he has been entrusted with Excalibur. The same director also guided George Formby through Get Cracking (1943), as he strives to ensure that the Minor Wallop Home Guard get the better of their rivals from Major Wallop while out on manoeuvres.

East Ender Tommy Trinder finds himself in considerably more peril when joins the Auxiliary Fire Service at the height of the Blitz in Basil Dearden's The Bells Go Down. Co-starring James Mason, this message comedy was followed by Humphrey Jennings's Fires Were Started (both 1943), which recreated the assault on London with real firefighters taking the roles of a crew called upon to tackle a warehouse blaze near a fully loaded munitions ship moored in the docks. The neo-realist style honed by Jennings owed much to his prewar involvement with the British Documentary Movement led by John Grierson, whose stints at the GPO and Crown film units had prompted Brazilian avant-gardist, Alberto Cavalcanti, to adopt a more naturalistic approach in pictures like Went the Day Well? (1942), an adaptation of Graham Greene's short story, 'The Lieutenant Died Last' that provided a chilling reminder of the need to be vigilant against the enemy within.

The way the postmistress leaps to the defence of Bramley End typifies the way in which women were depicted in Home Front narratives. Proving that a woman's war work is never done, Leslie Howard and Maurice Elvey's The Gentle Sex (1943) follows women from all walks of life volunteering for the Auxiliary Territorial Service, which also recruited Ethel Revnell and Gracie West in Philip Brandon's Up With the Lark (1943). Known to millions from the radio show, The Long and the Short of It, Ethel and Gracie had also confounded some fifth columnists while masquerading as members of the Women's Auxiliary Air Force in Redd Davis's The Balloon Goes Up (1942).

Having already cropped up in a couple of guises, Deborah Kerr plays a driver with the Mechanised Transport Corps in Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), which stars Roge Livesey as a Major-General in the Home Guard recalling his exploits in the Boer War and the Great War. Prime Minister Winston Churchill hated the film, but it reinforced Kerr's status as a rising star. She wasn't quite in the same popularity league as Forces Sweetheart Vera Lynn, but the attempt to turn her into a movie idol in Philip Brandon's We'll Meet Again (1942), Gordon Wellesley's Rhythm Serenade (1943) and Walter Forde's One Exciting Night (1944) didn't quite come off, even though she sings beautifully and more than holds her own as an actress.

Lynn also got to show off her bedside manner in ministering to an amnesiac and nursing was a recurring theme in wartime dramas. Lesley Brook helps sailor Richard Bird recover his memory after he is lucky to survive an attack on his ship in Maclean Rogers's I'll Walk Beside You (1943), while the same year saw architect Rosamund John volunteers to nurse and promptly fall for patient Stewart Grainger while also caring for his fiancée in Maurice Elvey's The Lamp Still Burns, which was one of the last films produced by Leslie Howard before his plane was shot down in the Bay of Biscay. Overcoming injury also proves key to Leslie Arliss's Love Story (1944), as pilot Stewart Granger has a race against time to find the source of a mineral that's vital to the British war effort before he loses his sight after being caught in an explosion. However, pianist sweetheart Margaret Lockwood is also in need of treatment, as she is suffering from a potentially fatal heart condition.

Granger would show a very different side, as the spiv making a move on Joy Shelton after soldier husband John Mills is called up in Sidney Gilliat's Waterloo Road (1945). Mills goes AWOL to sort out his rival, but his romance runs more smoothly in David Lean's This Happy Breed (1944), as he falls for Kay Walsh, the daughter of Robert Newton and Celia Johnson, who has lived next door to Mills's father and Newton's army pal, Stanley Holloway, since the end of the Great War. This wonderful slice of Clapham life between the wars is pipped, however, by Frank Launder and Sidney Gilliat's Millions Like Us (1943), which sees Patricia Roc go to work in an aircraft factory, while sister Joy Shelton joins the ATS and father Moore Marriott signs up to the Home Guard. Touching on so many themes and situations that would have been familiar to contemporary audiences, this typically astute saga shows how well-attuned Launder and Gilliat were to the everyday experience of ordinary men and women on the Home Front.

There were quirkier offerings, however, including Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's A Canterbury Tale, in which Land Girl Sheila Sim, British Tommy Dennis Price and American sergeant John Sweet try to work out who keeps pouring glue into girls' hair in the small Kentish town of Chillingbourne. Equally eclectic is Bernard Miles and Charles Saunders's Tawny Pipit (both 1944), which sees the villagers of Lipsbury Lea prepare for a visit from Russian sniper Lucie Mannheim while trying to prevent the local War Agricultural Executive Committee from ploughing up a field in which a rare pair of birds are nesting.

Such left-field topics suggested that the tide of the conflict had turned in the Allied favour and the whimsy became even more fanciful in Harry Watt's Fiddlers Three, which sees sailors Tommy Trinder and Sonny Hale, and Wren Diana Decker, get hit by lightning while visiting Stonehenge and be transported back to Ancient Roman times. The reason for the reverie in John Baxter's Dreaming (both 1945) is more prosaic, however, as Bud Flanagan starts hallucinating after being hit on the head by a heavy kitbag while he and buddy Chesney Allen are helping a Wren board a train.

There's also hijinx aplenty in Sidney Gilliat's The Rake's Progress (1945) as Rex Harrison's Eton- and Oxford-educated playboy fritters away the inter-war years before realising he owes a debt to society and displays reckless courage in uniform. The debonair Harrison is unusually on the wrong side of a romantic triangle in Herbert Wilcox's I Live in Grosvenor Square (1945), as his dashing major is engaged to WAAF Anna Neagle, only for her to fall for USAF pilot Dean Jagger, when he is billeted in the London home of her ducal father, Robert Morley. Neagle switches services in husband Wilcox's Piccadilly Incident as her Wren weds naval intelligence officer Michael Wilding after a chance meeting during an air raid. He marries again when she is presumed lost after her ship is torpedoed en route to Singapore. But Neagle has somehow survived and colonel Michael Redgrave also returns seemingly from the dead after wife Valerie Hobson has taken over his parliamentary seat in Compton Bennett's The Years Between (both 1946).

Home Front Nostalgia

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Home Front movie dropped out of vogue in the decade after the defeat of Fascism. Having lived through the trauma, audiences didn't need reminding of it, especially when there were so many 'now it can be told' adventures revealing previously secret aspects of the Allied victory. Consequently, items like Edward Dmytryk's adaptation of Graham Greene's The End of the Affair (1955) were relatively rare. In 1999, Neil Jordan remade the story about the illicit wartime romance between a civil servant's wife and an American author with the roles taken in the original by Peter Cushing, Deborah Kerr and Van Johnson being assumed by Stephen Rea, Julianne Moore and Ralph Fiennes.

The rise social realism in the late 1950s saw Sidney Hayers attempt to translate the 'kitchen sink' tone to the Home Front scenario in Violent Moment (1959), in which army deserter Lyndon Brook goes on the run after killing the girlfriend who has put their young son up for adoption. However, as the prospect of Armageddon became more of a reality during the Cold War arms race, the majority of the films revisiting the war years did so with a degree of nostalgia. For example, love blossoms between Donald Sinden and Barbara Murray when they are assigned to an experimental unisex anti-aircraft battery in Gilbert Gunn's Operation Bullshine (1959) and producer Peter Rogers and director Gerald Thomas dusted down the idea for Carry On England (1976), in which Patrick Mower and Judy Geeson play the lovebirds in the unit commanded by Kenneth Connor and his short-fused sergeant, Windsor Davies.

Lieutenant Ian Carmichael opts for a more laid-back method of command in Lewis Gilbert's Light Up the Sky! (1960), as he keeps turning a blind eye to the misdemeanours of siblings Tommy Steele and Benny Hill in the air-raid searchlight unit placed in the temporary control of Lance Corporal Victor Maddern. Specked with moments of unexpected poignancy, this is more nuanced than more raucous service comedies like Cyril Frankel's On the Fiddle (1961), in which Alfred Lynch is tricked into joining the RAF by a judge and begins pulling scams with the help of Gypsy buddy Sean Connery, and Frank Launder's Joey Boy (1965), which sees Harry H. Corbett racketeering in wartime London before being called up and doing his bit in Italy.

By far the best sitcom to emerge from the Home Front era was David Croft and Jimmy Perry's Dad's Army (1968-77), which is still a fixture on BBC2 over four decades after the last of its 80 episodes were transmitted. In 1971, Norman Cohen directed the big-screen spin-off that recapped how bank manager George Mainwaring (Arthur Lowe), chief clerk Arthur Wilson (John Le Mesurier), office junior Frank Pike (Ian Lavender), butcher Jack Jones (Clive Dunn), undertaker James Frazer (John Laurie), spiv Joe Walker (James Beck) and retired shop assistant Charles Godfrey (Arnold Ridley) formed the Warmington-on-Sea Home Guard platoon.

Despite the best efforts of Toby Jones and Bill Nighy, Oliver Platt's 2016 version of Dad's Army fell far short of the original's high standards and the same proved true of Gilles MacKinnon's 2016 remake of Alexander Mackendrick's Whisky Galore! (1949), an Ealing adaptation of a Compton MacKenzie novel about the efforts of the Home Guard's Captain Waggett (Basil Radford) to prevent the inhabitants of the Scottish island of Todday from recovering some of the 50,000 cases of Scotch that are left aboard the freighter, SS Cabinet Minister, when it runs aground in a dense fog. To date, however, nobody has shown any inclination to rework Norman Cohen's 1974 take on Spike Milligan's riotous wartime memoir, Adolf Hitler: My Part in His Downfall, in which the ex-Goon cameos as his own father, while the BAFTA-nominated Jim Dale plays the aspiring jazz musician who is forced to train with Arthur Lowe's artillery unit in Bexhill-on-Sea.

Easily the most innovative feature about Britain during the Second World War is Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo's It Happened Here (1964), which imagines what life would have been like had Operation Sea Lion been a success. Taking eight years to make with film stock donated by Stanley Kubrick, this story of acquiescence and resistance turns around Irish nurse Pauline Murray and is far more credible than the more comic-book antics in Edward and Ross McHenry's enjoyable Jackboots on Whitehall (2010), which features the voices of Ewan McGregor as a farmworker determined to fight for his homeland, Alan Cumming as a cross-dressing Hitler and Timothy Spall as Winston Churchill.

The cigar-smoking outsider who became the V-signing embodiment of the British bulldog spirit has been the subject of numerous screen accounts of his efforts to oppose appeasement and hold the country together in the face of the threat posed by the Luftwaffe. Albert Finney won a BAFTA and a Golden Globe for his display of inspirational irascibility in Richard Loncraine's The Gathering Storm (2002). However, the part passed to Brendan Gleeson in Thaddeus O'Sullivan's markedly less effective sequel, Into the Storm (2009). Timothy Spall resumed the role alongside the Oscar-winning Colin Firth as the stuttering George VI in Tom Hooper's The King's Speech (2010) before Gary Oldman won his own Best Actor statuette for his imposing work in Joe Wright's Darkest Hour (2017), which atoned in look and feel for its somewhat fanciful approach to historical fact.

As a major Atlantic seaport, Liverpool endured its share of bombardment and the everyday experiences of the Ashton, Briggs and Porter clans were related across 52 episodes in the admirable ITV series, A Family At War (1970-72). The city also provided the setting for Jim O'Brien's The Dressmaker (1988), which was adapted from a Booker Prize-nominated novel by Beryl Bainbridge to focus on the tensions between sisters Joan Plowright and Billie Whitelaw and their niece, Jane Horrocks. This was one of several challenging Home Front dramas produced in the wake of Michael Apted's The Triple Echo (1972), in which Glenda Jackson offers sanctuary to deserter Brian Deacon so he can help out on her farm while her husband is away. Jackson disguises Deacon as a woman, but snarling military policeman Oliver Reed takes a fancy to him while searching for runaways.

A stock Home Front storyline in this period saw lonely women succumb to the charms of exotic foreigners stationed in Blighty. John Schlesinger set the tone with Yanks, in which Lisa Eichhorn, Vanessa Redgrave and Wendy Morgan are swept off their feet by GIs Richard Gere, William Devane and Chick Vennera, while nurse Lesley-Anne Down can't resist bomber pilot Harrison Ford after a chance air-raid meeting in Peter Hyams's Hanover Street (both 1979). A quarter of a century after BBC reporter Sean Connery lost his heart to American war correspondent Lana Turner in Lewis Allen's Another Time, Another Place (1958), Scotswoman Phyllis Logan becomes besotted with Italian POW Giovanni Mauriello in Michael Radford's 1983 film of the same name. However, Kerry Fox caused even more of a stir by sleeping with African-American GI Courtney B. Vance in Paul Seed's The Affair (1995).

Teenager Sammi Davis gets pregnant by a Canadian soldier in John Boorman's five-time Oscar-nominated Hope and Glory (1987). But the main focus falls on her younger brother, Sebastian Rice-Edwards and no film has presented a fonder memoir of a wartime childhood, with the boy's sheer joy at his school being bombed ('Thank you, Adolf!') providing a standout moment. Directed for television by Jack Rosenthal, CP Taylor's play, And a Nightingale Sang (1989), offers an equally bittersweet insight into life in wartime Newcastle, although the scene shifts intriguingly to Canada to show how Brit abroad Anna Friel struggles to settle into her new surroundings with mother-in-law Brenda Fricker in Lyndon Chubbock's The War Bride (2001).

Friel was teamed with Catherine McCormack and Rachel Weisz do muck in on Tom Georgeson's Dorset farm in David Leland's The Land Girls (1998) and Devon provides the backdrop for Lone Scherfig's Their Finest (2016), which sees writer Gemma Arterton join the Ministry of Information to script a flag-waving account of the exploits of two sisters during the Dunkirk evacuation that took place between 27 May and 4 June 1940.

This pivotal moment of inglorious glory has featured in numerous films since Morland Graham and John Mills found themselves part of the British Expeditionary Force stranded in France in Ian Dalrymple's Old Bill and Son (1941). Mills was also on hand to provide some trademark stiff upper lippery in Leslie Norman's underrated Dunkirk (1958), which has since been followed by Alex Holmes's 2004 TV series, Dunkirk, Joe Wright's seven-time Oscar-nominated adaptation of Ian McEwan's Atonement (2007), and Adrian Vitoria's gung-ho commando actioner, Age of Heroes (2011). Nothing, however, can top the blend of intimacy and spectacle that Christopher Nolan achieved in Dunkirk (2017), which became the most successful British war movie of all time in making $526 million worldwide en route to landing eight Oscar nominations.

Behind Enemy Lines

While Alfred Hitchcock had warned against the danger looming on the continent in such classic thrillers as The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) and The Lady Vanishes (1938), the British film industry had tried not to sabre rattle for much of the 1930s for fear of exacerbating a precarious situation. Indeed, it wasn't until 1950 that Anthony Bushell recalled Austria's drift towards the 1938 Anschluss with Germany in The Angel With the Trumpet. Subsequently, the sense of what Jean Renoir described as Europe dancing on the edge of a volcano has been captured by John Duigan in the Anglo-Canadian saga about three friends in inter-war Paris, Head in the Clouds (2004), and Vicente Amorim in Good (2008), an adaptation of a CP Taylor play about a 1930s German academic (Viggo Mortensen) whose book on compassionate euthanasia is praised by the Nazi hierarchy.

Once the war was declared and the Wehrmacht rolled across borders with blitzkrieg speed, the best British film-makers could do was show solidarity with those resisting Nazi tyranny. As it wasn't easy to gather detailed information about life inside an occupied country, screenwriters tended to rely on educated speculation in shaping stories like Sergei Nolbandov's Ships With Wings, in which disgraced Fleet Air Arm pilot John Clements redeems himself on an embattled Greek island. The same year also saw Clive Brook make anti-Nazi broadcasts from within the Third Reich in Anthony Asquith's Freedom Radio and concentration camp escapee Movita Castenada seek sanctuary in a lighthouse with keeper Wilfrid Lawson and British spy Michael Rennie in Lawrence Huntington's Tower of Terror (all 1941).

Director Harold French commended the efforts of the Norwegian resistance in The Day Will Dawn, as fisherman's daughter Deborah Kerr helps intrepid journalist Hugh Williams blow up a U-boat base, and the Maquis in Secret Mission, which sees Williams joins forces with Michael Wilding, Roland Culver and Free French agent James Mason to sabotage a Nazi factory in the heart of La Patrie. This was also the destination for Welshman Clifford Evans and cohorts Tommy Trinder, Gordon Jackson and Constance Cummings in Charles Frend's The Foreman Went to France (all 1942).

The Dutch resistance movement is singled out for praise in both Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's One of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942), as the partisans abet the crew of a Wellington bomber after they bale out over the Zuider Zee, and Vernon Sewell and Gordon Wellesley's The Silver Fleet, which was produced by The Archers and stars Ralph Richardson as a shipbuilder who is accused of collaborating with the enemy. The scene switches to Belgium for Jeffrey Dell's The Flemish Farm, so that pilot Clifford Evans can recover the regimental colours of the air force unit he was forced to abandon in order to flee to Britain. But, after Sergei Nolbandov paid tribute to the Yugoslavian patriots refusing to buckle in the face of the Nazi-Chetnik alliance in Undercover (all 1943), the focus turned away from plucky foreigners standing up to Fascism and on to heroic Allied forces incrementally liberating the continent following D-Day on 6 June 1944.

Postwar Perspectives

Few combat films were made in the immediate aftermath of the war, with the emphasis in Compton Bennett's So Little Time (1952) being more on the melodramatic taboo involved in Belgian Maria Schell and German colonel Marius Goring bonding over a shared love of music. Conflicted loyalties also rear their heads in Brian Desmond Hurst's Malta Story (1953), as islander Nigel Stock returns on a spying mission after studying in Italy, and in Michael McCarthy's The Traitor (1957), as resistance leader Donald Wolfit reassembles his unit to expose the quisling who had betrayed them to the Nazis.

Having turned a blind eye on Lilli Palmer's convent sheltering Jewish children, Italian major Ronald Lewis also has reservations about obeying the orders of German superior Albert Lieven in Ralph Thomas's Conspiracy of Hearts (1960). Thomas worked regularly with Dirk Bogarde, but it was Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger who directed him in Ill Met By Moonlight (1957), as Bogarde's British officer conspires with partisans on Crete to kidnap German general Marius Goring. The dangers of collusion were outlined by Max Vanel's The Silent Invasion (1962), which sees Petra Davies vow vengeance after her brother is executed by the Nazis in 1940, as one of two scapegoats in the French town of Mereux.

Despite being directed and headlined by Americans Anthony Mann and Kirk Douglas, The Heroes of Telemark (1965) was a British reconstruction of the Norwegian resistance's 1942 bid to prevent the German's from building a heavy water plant. The murder that same year of a prostitute in German-occupied Warsaw sparks the action in Anatole Litvak's adaptation of Hans Helmut Kirst's bestseller, The Night of the Generals (1967), whose simmering intensity is matched by that of Sam Peckinpah's Cross of Iron (1977), an adaptation of a Willi Heinrich novel that follows James Coburn and James Mason's platoon to the Eastern Front in 1943.

An air of eager escapism pervades Michael Winner's Hannibal Brooks (1969), which accompanies British POW and an elephant named Lucy across the Alps to a zoo in Innsbruck. The lighter side is also to the fore in Bob Kellett's Our Miss Fred (1972), as entertainer Danny LaRue dons drag in order to avoid capture in Occupied France, and in Roy Boulting's Soft Beds, Hard Battles (1974), which allowed Peter Sellers to play six roles (including Hitler) in a story about the systemic murder of high-ranking German officers in a Parisian brothel.

It's not too difficult to trace a line between this farce and Jimmy Perry and David Croft's sitcom, 'Allo 'Allo (1982-92), which pastiched the BBC series Secret Army (1978-79), about a Belgian resistance unit's bid to repatriate some British airmen. Another popular series, this time produced by ITV, was Enemy At the Door (1980), which chronicled life on the only part of the United Kingdom to be occupied by the Nazis. The amazing story told in Terence Young's Triple Cross (1966) is entirely factual, as Christopher Plummer plays safecracker Eddie Chapman, who offered his services to the occupying Nazis on Jersey, only to turn double agent under the codename, Zigzag.

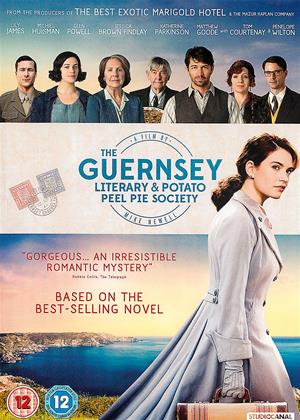

Nothing quite so dramatic happens to the Dorr, Mahy and Jonas families on the fictional territory of Saint Gregory in ITV's epic mini-series, Island At War (2004). But things are all too real in Christopher Menaul's Another Mother's Son (2017), which recalls the courageous sacrifice made by Jersey resident Louisa Gould (Jenny Seagrove) in protecting a Russian escapee from a nearby labour camp. Much of the action in Mike Newell's The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society (2018) takes place after the war, but the initial scenes in this adaptation of Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows's bestseller take place under the German occupation in 1941.

The role of the Papacy during the Holocaust has come under close scrutiny, but Jerry London celebrates the heroism of Monsignor Hugh O'Flaherty in The Scarlet and the Black (1983), which stars Gregory Peck in an adaptation of JP Gallagher's book, The Scarlet Pimpernel of the Vatican. Paris provides the setting for Waris Hussein's 1985 take on Arch of Triumph, Erich Maria Remarque's novel about an Austrian doctor helping protect his Jewish patients, which saw Anthony Hopkins and Lesley-Anne Down assume the roles that had been taken by Charles Boyer and Ingrid Bergman in Lewis Milestone's 1948 original. Continuing the pernicious theme of persecution, Clive Owen's gay Berliner is hounded by Sturmabteilung officer Nikolaj Coster-Waldau in Sean Mathias's version of Martin Sherman's acclaimed play, Bent (1997), while Adrien Brody won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance as musician Wladyslaw Szpilman enduring the perils and privations of the Warsaw Ghetto in Roman Polanski's The Pianist (2002).

Just as the Pole drew on his own memories of the occupation, so Franco Zeffirelli recalled the kindness he was shown by various British and American ex-pat ladies (played by Joan Plowright, Maggie Smith, Cher, Lily Tomlin and Judi Dench) in Tea With Mussolini (1999). The gentility of this account of life in Fascist Italy contrasts starkly with the desperation of the stand-off between Russian and German snipers Jude Law and Ed Harris in Jean-Jacques Annaud's Enemy At the Gates (2001), a reconstruction of the pitiless Siege of Stalingrad that finds a companion in Aleksandr Buravsky's Attack on Leningrad (2009), another co-production which charts the 1941 friendship between American journalist Mira Sorvino and Soviet policewoman Olga Sutulova.

A quirkier biopic, John Henderson's Two Men Went to War (2002), sees Kenneth Cranham and Leo Bill play the Dental Corps duo of Sergeant Peter King and Private Leslie Cuthbertson, who launched their own invasion of France with a bag of stolen grenades after writing to inform Winston Churchill (David Ryall) of their intentions. The harsher realities of the Occupation are laid bare by André Téchiné in Strayed (2003), as Gaspard Ulliel tries to keep widowed teacher Emmanuelle Béart and her two children away from the advancing Wehrmacht in June 1940. Comparable to this road movie is Cate Shortland's Lore (2012), which is set in Germany in May 1945, as concentration camp survivor Kai Malina helps teenager Saskia Rosendahl and her four siblings, in spite of the fact that their parents were committed Nazis.

British money was involved in these co-productions, as it was in Paul Verhoeven's Black Book (2006), in which Jewish woman Carice van Houten joins the Dutch resistance; Petter Næss's Cross of Honour (2012), which sees German and British soldiers call a truce after being stranded in Norway; Saul Dibb's Suite Française (2014), which returns to 1940 to chart the relationship that develops between Parisienne Michelle Williams and German officer Matthias Schoenaerts after her husband is taken prisoner; and Sean Ellis's Anthropoid (2016), which follows Fritz Lang's Hangmen Also Die, Douglas Sirk's Hitler's Madman (both 1943) and John Farrow's The Hitler Gang (1944) in dramatising the assassination of Reichsprotektor Reinhard Heydrich in Prague in June 1942.

The most intriguing film inspired by this event, however, is Humphrey Jennings's The Silent Village (1943), which reimagines the reprisal slaughter in the Czech mining community of Lidice by setting it in the Welsh pit village of Cwmgiedd and casting working miners in the lead roles. Jennings was the undisputed poet of British war cinema and his evocative documentaries can be found on the three volumes of the BFI's Humphrey Jennings Collection.