Eighty-five years ago, a change of government in France coincided with a shift in tone in the national cinema. Paradoxically blending gritty authenticity with stylised lyricism, Poetic Realism took a darker turn, as Europe drifted towards war. Some contemporary critics complained that such sombre studies of working-class angst were little more than 'long poems to discouragement'. But Cinema Paradiso begs to disagree in celebrating 1930s French film and its enduring legacy.

Having been deprived of Hollywood films for the duration of the Nazi Occupation, French critics revelled in catching up with the back catalogues of the various studios at the end of the Second World War. Many noticed a darker tone in pictures like John Huston's The Maltese Falcon (1941), Billy Wilder's Double Indemnity (1944) and Howard Hawks's The Big Sleep (1946). In dubbing these downbeat lowlife thrillers, 'film noir', these cineastes often overlooked the fact that French film-makers had also been casting shadows to explore the darker side of human nature for much of the previous decade. But, as Poetic Realism had been a mood rather than a movement, its significance hadn't perhaps been immediately appreciated.

A Floundering Founder

Thanks to the efforts of Auguste and Louis Lumière, France could claim to be the birthplace of the moving image, although some alternative histories can be found in the Cinema Paradiso article, What to Watch Next If You Liked The Magic Box. Users can learn from Jacques Meny's Méliès the Magician (1997) and Pamela B. Green's Be Natural: The Untold Story of Alice Guy-Blaché (2018) about the impact made on early cinema by music-hall magician Georges Méliès and studio secretary Alice Guy. But the Great War forced the closure of studios across Europe and, while Louis Feuillade helped refine the screen serial with Les Vampires (1915) and Fantômas (1918), the newly established Hollywood rapidly became the world's film capital.

As America had taken control of the mainstream, critic Louis Delluc sought to reclaim the avant-garde for France. In addition to setting up a network of ciné-clubs, also Delluc made such films as Fièvre (1921), which sought to instil a focus on everyday events and settings. His notion of 'photogénie' encouraged film-makers to create their own vision of reality and theorists have labelled this approach, 'Impressionism'. Among those toheed the call were Germaine Dulac ( The Smiling Madame Beudet, 1922 - which can be found on Early Women Filmmakers, 1911-1940 ), Jean Epstein ( Coeur Fidèle, 1923), Dimitri Kirsanoff ( Ménilmontant, 1926), Abel Gance ( Napoléon, 1927) and Marcel L'Herbier ( L'Argent, 1929).

By contrast, the influence of Dada could be felt in the Surrealist cinema that emerged towards the end of the decade. Alongside artists like FernandLéger ( Ballet Mécanique, 1924), Marcel Duchamp ( Anaemic Cinema, 1926) and Man Ray ( Les Mystères du Château de Dé, 1929), aspiring film-makers likeRené Clair ( Entr'acte, 1924) and Luis Buñuel ( Un Chien Andalou, 1929 & L'Age d'or, 1930 - which were made in collaboration with Spanish painter Salvador Dalí) tapped into dream logic to create films that were so provocative that they occasionally caused riots at the venues screening them.

While these films helped make cinema 'the Seventh Art', the majority of French audiences preferred more mainstream fare, including the pioneering silent slapstick of Max Linder, whose antics can be seen in James M. Anderson's All in Good Fun (1955), which can be rented from Cinema Paradiso on The Renown Pictures Comedy Collection, Volume 1. However, French cinema took some time to respond to the coming of sound, following the success of Alan Crosland's The Jazz Singer (1927), and Poetic Cinema arose out of an attempt to break away from the endless round of musicals, comedies and stage transfers that held sway at the box office.

Taking a Page

With its studio-bound settings and enveloping shadows, Poetic Realism has its own distinctive aesthetic. Yet, these tales of everyday life in the lower depths of society have their origins on the page. As far back as the 18th century, the roman noir (the French equivalent of the gothic novel) had examined life on the margins in the sprawling cities. A notable later example, Victor Hugo's L'Homme qui Rit (1869), was filmed by Paul Leni as The Man Who Laughs (1928), a silent classic that would come to influence the look of The Joker in the Batman franchise.

Hugo's brand of realism was also evident in The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831) and Les Misérables (1862), both of which have been filmed on numerous occasions, as a trip to the Cinema Paradiso search line will testify. His influence can be seen in the Comédie humaine novels of Honoré de Balzac, who is represented at Cinema Paradiso by Gareth Davies's Cousin Bette (1971), Jacques Rivette's La Belle Noiseuse (1991) and Don't Touch the Axe (2004), and Yves Angelo's Le Colonel Chabert (1994).

Among those who followed Balzac's lead were Charles Dickens and HenryJames, as well as Gustave Flaubert - whose masterpiece, Madame Bovary, has been adapted by Rodney Bennett (1976) , Claude Chabrol (1991) , Tim Fywell (2001) and Sophie Barthes (2014) - and Émile Zola, whose imposing Rougon-Macquart series of novels yielded such contrasting cinematic gems as Marcel L'Herbier's L'Argent (1929), Marcel Carné's Thérèse Raquin (1953), Fritz Lang's Human Desire (1954) and René Clément's Gervaise (1956).

François Truffaut and his fellow critics at Cahiers du Cinéma would turn against polished pictures like the latter and place them within a ridiculed 'Tradition of Quality' because of their emphasis on florid scripts and plush production values. On becoming a director, however, Truffaut would be inspired by both realist fiction and Poetic Realist cinema. A particular literary influence on the nouvelle vague was Pierre Mac Orlan, whose 'fantastique social' experiments were emulated by the likes of Eugène Dabit. Indeed, as we shall see, they each produced works that were filmed to atmospheric effect by Marcel Carné.

A couple of Belgians also wrote in the same vein, Georges Simenon and Stanislas-André Steeman, whose The Murderer Lives At 21 and Quai des Orfèvres were filmed by Henri-Georges Clouzot in 1942 and 1946 respectively. The prolific Simenon is best known for creating pipe-smoking police inspector Jules Maigret, who was played on the big screen by such French stalwarts as Pierre Renoir and Jean Gabin, as well as by Charles Laughton in Burgess Meredith's The Man on the Eiffel Tower (1949).

Maigret has also been essayed on television in France by Bruno Cremer (1992-2005) and in this country by RupertDavies (1960-63), Michael Gambon (1992) and Rowan Atkinson (2016-17) . However, Simenon also produced dozens on non-related tomes and Cinema Paradiso can offer users such diverse titles as Julien Duvivier's Panique (1946), Harold French's The Man Who Watched Trains Go By (1952), Phil Karlson's The Brothers Rico (1957), Pierre Rouve's Stranger in the House (1967), Bertrand Tavernier's The Watchmaker of St Paul (1973), Patrice Leconte's Monsieur Hire (1989), Claude Chabrol's Betty (1991), Pierre Jolivet's In All Innocence 1998), Cédric Kahn's Red Lights (2003), and Béla Tarr's The Man From London (2007).

But how did all this littérature de haut et bas niveau (high- and lowbrow to the likes of us) transform French cinema?

Making a Style Statement

If the literary inspiration for Poetic Realism was primarily French (or, at least, Francophonic), its visual impetus came from further afield. Cinema Paradiso regulars will have already read about the extensive influence of 'Deutscher Expressionismus' and the 'Kammerspielfilm' in the article, 100 Years of German Expressionism. But it's worth reiterating the importance of films like F.W. Murnau's The Last Laugh (1924), G.W. Pabst's Pandora's Box (1929) and Fritz Lang's M (1931) on Poetic Realism. Another key influence was People on Sunday (1929), an offbeat tale of daily life in Berlin that was directed by Robert Siodmak and Edgar G. Ulmer and counted Billy Wilder and Fred Zinnemann amongst its crew.

The stylised naturalism of the latter (which was hailed as 'a film without actors' because of its non-professional cast) reflected a shift in photographic aesthetics at the outset of the global downturn that followed the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Indeed, the arrival in Paris of such Eastern European shutterbugs as André Kertész, Gyula Halász (aka Brassaï), Germaine Krull and François Kollar led to the introduction of a lyrical chiaroscuro style in the picture magazines that had started to flourish in the early 1930s after technological improvements had been made in the print reproduction of photographs.

Around this same period, German cinematographers like Curt Courant and Eugen Schüfftan started influencing such French counterparts as Claude Renoir, Jules Kruger, Nicolas Hayer and Marc Fossard, who were given time to light and compose their shots on street sets and interiors built in the studio by such revered designers as Lazare Meerson, Jacques Krauss and Alexandre Trauner.

The controlled shooting conditions also allowed technicians to import tropes from both Impressionist and Surrealist cinema, some of which were achieved in-camera and others, like superimpositions and dissolves, that were created in post-production, as were the evocative scores of Georges Auric, Maurice Jaubert, Joseph Kosma and Arthur Honegger, which contributed to the distinctive sense of 'atmosphere' that was whipped up in the screenplays of Jacques Prévert. Charles Spaak, Henri Jeanson and Jean Aurenche.

The Depression led to instability within the French film industry, with small companies risking all on the success of a single picture. Although there was a resistance to duplicating the factory system operating in Hollywood, the formation of larger production entities like La Société Nouvelle des Établissements Nouvelle Gaumount enabled producers to release between 100-120 features each year. These companies were also able to ensure that the studios at Billancourt and Epinay could keep pace with Paramount's facility at Joinville.

They were also sufficiently stable to give directors a degree of creative latitude by being able to balance artistic ambition and commercial expectation. Moreover, they could afford the fees of the leading stars of the day, including Dita Parlo, Françoise Rosay, Arletty, Mireille Balin, Annabella, Michèle Morgan, Michel Simon, Raimu, Jules Berry, Louis Jouvet, Pierre Fresnay and Jean Gabin.

The latter became something of a barometer of French self-esteem either side of the election of the Popular Front alliance in May 1936, which seemed to usher in a new dawn of peace, reform and prosperity before it collapsed in October 1938, leaving La France divided at the very moment that its Nazi neighbour was becoming increasingly powerful and bellicose.

The Forerunners

Those with fond memories of the Museum of the Moving Image on London's Southbank will recall the mock-up of the street in René Clair's Under the Roofs of Paris (1929), an early French musical that presaged the look and feel of Poetic Realism. Having made such silent gems as The Italian Straw Hat (1927), which really should be available on DVD in this country, Clair dallied with the Surrealists before departing for America after anticipating the optimism of the Popular Front era with Le Million and À Nous la Liberté (both 1931). Cinema Paradiso patrons can catch up with other Clair titles by using the search line, including those he made in France after his postwar return from Hollywood, including Les Grandes Manoeuvres (1955), which starred Michèle Morgan, Gérard Philipe and a young Brigitte Bardot.

Like Clair, Belgian Jacques Feyder also worked in Britain and America. Renowned for silents as Crainquebille (1922), he worked with Greta Garbo on her last silent, The Kiss (1929), and first talkie, Anna Christie (1930), as he handled the German-language version of Clarence Brown's English original.

Back in France, Feyder starred actress wife Françoise Rosay in a trio of marvellous films scripted by Charles Spaak. Sadly, Pension Mimosas (1935) isn't available. But Cinema Paradiso customers can discern the nascent Poetic Realist style in Le Grand Jeu (1934), a dopplegänger romance set against a Foreign Legion backdrop in Morocco, and revel in the screwball satire of La Kermesse Héroïque (1936), as the citizens of the small Flemish town of Boom prepare to face a Spanish invasion in 1616.

A handful of other features hinted at the socio-stylistic shift to come, including such frustratingly elusive titles as Jean Grémillon's La Petite Lise (1930), Anatole Litvak's Coeur de Lilas (1932), Julien Duvivier's La Tête d'un Homme (1933) and Pierre Chenal's La Rue sans Nom (1934), which have never been made available on disc in the UK. Fortunately, the same is not true of the work of Jean Vigo, whose regrettably short life is recalled in Julien Temple's biopic, Vigo: Passion For Life (1998), which features James Frain in the title role.

The son of anarchist Miguel Almereyda, Vigo had been sent to boarding school under the assumed name of Jean Sales. He recalled his experiences in the bitingly brilliant Zéro de Conduite (1933), which proved a huge influence on François Truffaut's debut feature, The 400 Blows (1959) and Lindsay Anderson's If.... (1968). Running for around 40 minutes, this denunciation of oppression can be rented from Cinema Paradiso on a disc that also contains Vigo's experimental shorts, contains À Propos de Nice (1930) and Taris (1931), as well as his feature masterpiece, L'Atalante (1934).

Widely regarded as the first true work of Poetic Realism, this affecting drama takes the audience on to a barge plying its trade along the River Seine, as new bride Dita Parlo has to squeeze into the cramped quarters below deck with skipper husband Jean Dasté, cabin boy Louis Lefebvre and old hand Michel Simon and his numerous cats. However, Parlo struggles to acclimatise and seeks adventure in a Paris photographed by Boris Kaufman with the same acute sense of place that brother Mikhail had achieved in their older sibling Dziga Vertov's Soviet montage masterpiece, The Man With a Movie Camera (1929). Yet, it was the sequence in which Dasté dives into the river and sees Parlo's superimposed face smiling back wherever he looks that brought lyricism to the realism and helped establish a new form of French film-making.

The Masters: Jean Renoir

Tragically, tuberculosis claimed Vigo at the age of 29 in October 1934. But his vision was shared by the likes of Jean Renoir, the son of the Impressionist artist, Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Gilles Bourdos recalls the relationship between father (Michel Bouquet) and son (Vincent Rottiers) in Renoir (2012), which centres on their mutual attraction to the painter's last model, Andrée Heuschling (Christa Théret), who would find brief fame in her director husband's silent films as Catherine Hessling.

It was the coming of sound that enabled Renoir to make his mark. He memorably directed Michel Simon as the hobo who strays into high society in Boudu Saved From Drowning (1932) before venturing to Provence for Toni (1934). This account of a love triangle involving Italian migrant Toni (Charles Blavette), his French landlady, Marie (JennyHélia), and a Spanish worker, Josefa (Celia Montalván) exerted a considerable influence on assistant director, Luchino Visconti, who would be one of the driving forces of Italian neo-realism with La Terra Trema (1948), which centred on a community of Sicilian fishermen.

Returning to Paris, Renoir joined the Ciné-Liberté co-operative and embraced the ethos of the Popular Front in Le Crime de Monsieur Lange (1935), in which the workers at a publishing company join Western writer Amédée Lange (René Lefèvre) in taking the reins after indebted owner Batala (Jules Berry) fakes his own death. Scripted by Jacques Prévert and made in collaboration with the agit-prop theatre troupe, Groupe Octobre, the film led to Renoir being invited by the Communist Party to contribute to the anti-Fascist anthology, La Vie est à Nous (1936).

Following an adaptation of Maxim Gorky's The Lower Depths (1936), Renoir produced one of the finest paeans to pacifism in screen history. Co-written by Charles Spaak, La Grande Illusion (1937) examines the links between patriotism and class during the Great War, as French flying ace Captain de Boëldieu (Pierre Fresnay) feels closer to his invalided German captor, Major von Rauffenstein (Erich von Stroheim), than he does to his respectively working-class and Jewish compatriots, Lieutenant Maréchal (Jean Gabin) and Lieutenant Rosenthal (Marcel Dalio).

Renoir would examine the concept of patriotism again in La Marseillaise, which tells the story behind the composition of the French national anthem. But, by the time he came to adapt Zola's La Bête Humaine (both 1938), the political tide had turned and pessimism seeps out of every frame, as train driver Jacques Lantier (Jean Gabin) develops a fatal attraction to Séverine (Simone Simon), the young wife of uncaring deputy stationmaster, Roubaud (Fernand Ledoux).

The tone was even more sombre, however, La Règle du Jeu (1939), an upstairs-downstairs satire on class manners and mores that drew on the stage comedies of Marivaux and Beaumarchais. Technically, Renoir's use of deep-focus photography and long takes would presage what critic André Bazin would call the 'mise-en-scène' style of shooting that would shape the look of such 1950s Max Ophüls masterworks as La Ronde (1950), Le Plaisir (1951), Madame De... (1953) and Lola Montès (1955), as well as the earliest nouvelle vague outings. But it was the depiction of the aristocracy 'dancing on a volcano' that so dismayed critics and audiences that the most expensive film produced in France to that point was banned in October 1939 for undermining wartime morale.

Following the Nazi invasion, propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels declared it 'public cinematographic enemy number one' and the film was thought to be lost forever after an Allied bombing raid on the film laboratory at Boulogne-sur-Seine in 1942. However, an 86-minutes print was discovered in1946, the same year that Renoir's 1936 take on Guy de Maupassant's Partie de Campagne finally received a release. Thirteen years later, Renoir approved a painstaking restoration that resulted in a 106-minute version of La Règle de Jeu being released and hailed a masterpiece. By this time, the director was approaching the end of his career and he never quite returned to his Poetic Realist peak. Yet the films he made in Hollywood and back in France are still fascinating and a number are available in high-quality disc from Cinema Paradiso. You know what to do.

The Masters: Marcel Carné

If Renoir epitomised the optimistic Popular Front brand of Poetic Realism, the daunting, almost noirish version was very much the preserve of Marcel Carné. A former critic and assistant to Jacques Feyder, Carné made his feature bow with Jenny (1936), the story scripted by poet Jacques Prévert of a ménage involving a nightclub owner, her daughter and a Parisian gangster.

Although it had moments of stylised lyricism, the picture was pretty conventional - unlike its follow-up, Drôle de Drame (1937), a spirited farce set in England that centres on the Bishop of Bedford (Louis Jouvet) coming to the conclusion that his botanist cousin, Irwyn Molyneux (Michel Simon), has murdered his wife (Françoise Rosay), when his sole crime is writing racy novels under a pseudonym. Co-scripted by Prévert from Scotsman J. Storer Clouston's novel, His First Offence, this left-field romp couldn't be further from the doom-laden trilogy that followed, which almost defined Fatalist Realism's tendency to focus on margin dwellers being deprived of a last chance of happiness by capricious fate.

Adapted by Prévert from a Mac Orlan bestseller, Le Quai des Brumes (1938) follows the misfortunes in Le Havre of Jean (Jean Gabin), an army deserter whose destiny is sealed the moment he tries to protect 17-year-old Nelly (Michèle Morgan) from her sinister godfather, Zabel (Michel Simon), and a local gangster, Lucien (Pierre Brasseur). With Alexandre Trauner's claustrophobic sets being bathed in shadows by Eugen Schüfftan, Carné suffuses the melodrama with a melancholy that is underlined by Maurice Jaubert's score.

A clip from the film can be seen in Joe Wright's adaptation of Ian McEwan's lauded Second World War novel, Atonement (2007). But, in his next project, Carné was keen to avoid references to domestic politics or the deteriorating diplomatic situation following Germany'sinvasion of Czechoslovakia. Consequently, his adaptation of Eugène Dabit's Hôtel du Nord (1938) concentrates on the ramifications for pimp Edmond (Louis Jouvet) and prostitute Raymonde (Arletty) of the failed suicide pact between Pierre (Jean-Pierre Aumont) and Renée (Annabella).

Scripted by Jean Aurenche and Henri Jeanson and filmed at Billancourt on Trauner's recreation of the Canal Saint-Martin milieu, this compelling picture has been somewhat overlooked because it was followed by Le Jour se Lève (1939), which has been seen by some as the suicide note of a nation on the brink. Written by Prévert and Jacques Viot, the story flashes back to show why foundry worker François (Jean Gabin) barricades himself into a garret after shooting dog trainer Valentin (Jules Berry) for his treatment of florist Françoise (Jacqueline Laurent) and his on-stage assistant, Clara (Arletty).

Suppressed by the Nazis, the film was almost lost forever when RKO tried to destroy existing prints to remove any competition to Anatole Litvak's 1947 remake, The Long Night. But such Philistinic vandalism failed to expunge a masterly noir that looks magnificent in the uncut 75th anniversary Blu-ray version. But Carné's talent for capturing the national mood prompted the Nazis to keep a close eye on him during the Occupation. Nevertheless, he managed to slip allegorical messages into Les Visiteurs du Soir (1942), which was set in 1485 and joins envoys Gilles (Alain Cuny) and Dominique (Arletty) on an earthly mission for the Devil (Jules Berry).

Annoyingly, this underrated picture is currently unavailable. But Cinema Paradiso offers ravishing DVD and Blu-ray editions of Carné's hymn to the spirit of France, Les Enfants du Paradis (1945), which was filmed under the noses of the Germans and released to great fanfare following the Liberation. Set in the 1830s, the narrative considers the impact that a demi-mondaine named Garance (Arletty) has upon mime Baptiste Deburau (Jean-Louis Barrault), actor Frédérick Lemaître (Pierre Brasseur), nobleman Édouard de Montray (Louis Salou) and thief Pierre-François Lacenaire (Marcel Herrand). Although not a work of Poetic Realism in the truest sense, it saw Carné find a new use for the 'fantastique social' style that had become his trademark.

It also proved to be his high watermark, as critics lamented a loss of form in his final outings with Prévert, Les Portes de la Nuit (1946) and La Marie du Port (1950). Indeed, it says much that only Thérèse Raquin (1952) and L'Air de Paris (1954) are available to rent from the postwar releases that are long overdue reappraisal. But Carné's achievement during his first decade as a director remains enviably impressive.

Les Autres

Such was the severity of the 1950s Cahiers du Cinéma assault on what it dismissively called 'cinéma du papa' that many of those who had prospered with Poetic Realism had their reputations so badly damaged that they some have yet to recover. Among these unfortunates is Julien Duvivier, who had made his directorial debut in 1919 and would keep producing pictures for almost the next 50 years. Yet, even though he spent nearly a decade in Hollywood, relatively few of his films are available on disc on either side of the Channel.

Despite being key works of Poetic Realism, neither La Bandera (1935) nor La Belle Équipe (1936) are currently on offer. ButDuvivier's evocation of the Casbah quarter of Algiers is so potent that Pépé le Moko (1937) is available from Cinema Paradiso and should be on everybody's must-see list. Jean Gabin is on typically pugnacious form as the gangster holding court while hiding from the French police. However, he possesses that noirish flaw that will draw him out of the shadows and into the flame of Parisian chanteuse, Gabby Gould (Mireille Balin).

Hollywood recognised the story's exotic appeal and remade it twice, as John Cromwell's Algiers (1937) and John Berry's musical, Casbah (1948), with Charles Boyer and Hedy Lamarr and Tony Martin and Yvonne De Carlo in the respective leads. Joshua Logan would also musicalise Fanny (1961), which had originally been the central strand in the 1930s Marseille trilogy that had been based on the writings of Marcel Pagnol.

Alexander Korda had directed Marius (1931), while Marc Allégret made Fanny (1932). Pagnol himself handled César (1936), which turned out to be the only part of the triptych not reworked by Daniel Auteuil after he had directed himself in Marius (2013) and Fanny (2013). The most celebratedPagnol adaptations were Claude Berri's Jean de Florette and Manon des Sources (both 1986) and the Yves Robertdualogy of Le Château de ma Mère and La Gloire de mon Père (both 1990), which did much to boost arthouse cinema-going in the UK. But there is also much to enjoy in Peter Sellers's Mr Topaze (1961) and Auteuil's The Well-Digger's Daughter (2011).

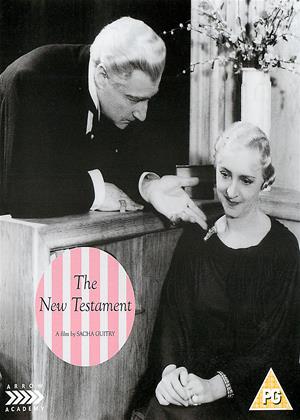

Bizarrely, none of the films on which Pagnol worked personally are available on disc in the UK. Come on, someone! At least a few of Sacha Guitry's distinctive features have found their way to these shores. Indeed, Cinema Paradiso can offer users a pair of double bills, which are comprised of The New Testament and My Father Was Right (both 1936) and Let's Make a Dream (1936) and Let's Go to the Champs-Elysées (1938). The later comedy, Poison (1951), is also on offer, but not Guitry's standout picture, The Story of a Cheat (1936), whose self-reflexive refusal to stick to the movie-making rules made it a major influence on the nouvelle vague.

Two more films from this period worthy of note, although neither is particularly Poetic Realist in style, are Raymond Bernard's Wooden Crosses (1932) and Les Misérables (1934). We should also highlight a couple of Jean Grémillon's wartime features, Remorques (1941) and Lumière d'été (1943), which did echo the style of the previous decade, unlike The Love of a Woman (1953), which is available exclusively on Blu-ray. Also worth mentioning is Pierre Chenal's Le Dernier Tournant (1939), which was the first screen adaptation of James M. Cain's pulp classic, The Postman Always Rings Twice, which was remade by Luchino Visconti as Ossessione (1942) and under its own title by Tay Garnett in 1948, with John Garfield and Lana Turner as the star-crossed lovers.

The Legacy

Scripted by Charles Spaak, Chenal's tale of lust and murder was dubbed 'film noir' before several years critic Nino Frank applied the term to the postwar influx of American thrillers. Indeed, what might be termed Noir Realism could also be detected in Henri-Georges Clouzot's chilling study of wartime collaboration, Le Corbeau (1943), while what we might term Escapist Realism permeated Jean-Pierre Melville's variation on the same contentious theme, Le Silence de la Mer (1949).

In the decade that followed, Poetic Realism mutated into neo-realism in Italy and film noir in Hollywood. Each format would have a profound influence on global cinema. The former, for example. shaped the Social Realist style that would emerge in Britain in the late 1950s in an effort to translate the 'kitchen sink' saga to the screen from both the page and stage. This proletarian naturalism, in turn would impact upon the Czech New Wave (see Cinema Paradiso's Top 10 Czech Films article) and continues to be felt in the work of Ken Loach. Mike Leigh and the Dardenne brothers.

The fact that the term 'neo-noir' is still in vogue proves the enduring influence of film noir. In postwar France, it could be felt in such classics as Jacques Becker's Falbalas (1945) and Touchez pas au Grisbi (1954), Jules Dassin's Rififi (1955), and Jean-Pierre Melville's Bob le Flambeur (1955) and Le Doulos (1963). These all proved popular with Cahiers critics Claude Chabrol ( Les Cousins, 1959), Jean-Luc Godard ( À Bout de Souffle, 1960) and François Truffaut ( Shoot the Pianist, 1960), who would all put their own spin on the noir style during the early phaseof the nouvelle vague. As would Louis Malle in Lift to the Scaffold and Les Amants (both 1958).

Finally, Poetic Realism brought a new humanism to cinema, most notably through Renoir's famous maxim that 'everyone has their reasons'. This is too broad a legacy to pin down here, but use the Cinema Paradiso search line to check out the works of Vittorio De Sica, Satyajit Ray (who worked with Renoir on The River, 1951), Yasujiro Ozu, Robert Bresson, Akira Kurosawa, Stanley Kramer, Eric Rohmer, Aki Kaurismäki, Abbas Kiarostami and Olivier Assayas and you'll get our drift.