As one of the most significant films in screen history celebrates its centenary, Cinema Paradiso begins 2025 by focussing on Battleship Potemkin (1925).

As Cinema Paradiso members might remember from our Brief History of Soviet Silent Cinema, film-making had been thriving in Tsarist Russia right up to the outbreak of the Great War. Indeed, its ability to reach people in every corner in the vast realm persuaded Bolshevik leader Vladimir Ilych Lenin to declare, 'Of all the arts, for us, the cinema is the most important.'

In order to control the message, he nationalised the film industry and appointed wife Nadezhda Krupskaya to run the cinema sub-section of the People's Commissariat for Education. In June 1918, however, the Moscow Cinema Committee started sponsoring a weekly film series entitled Kino-Nedelya. But the best-known propaganda newsreel was Kino Pravda, which was produced by editor David Kaufman. Going by the name of Dziga-Vertov (or 'spinning top'), he had left people with no doubt as to his intentions when he launched a manifesto in which he averred, 'We proclaim the old films. based on romance, theatrical films and the like, to be leprous.' To replace them, Vertov, cameraman brother, Boris Kaufman, and editor wife, Elizaveta Svilova came up with 23 editions of their lively mix of news and sloganising, which were produced for exhibition on special agit-prop trains, which travelled the length and breadth of the vast country to make citizens feel part of the revolution.

Vertov would carve his place in cine-history with Man With the Movie Camera (1928). But not everyone has heard of Lev Kuleshov, the head of the State Film Institute (VGIK) in Moscow, whose notions on editing helped transform global cinema, as his workshop attracted the likes of Vsevolod Pudovkin and, for a brief time, Sergei Eisenstein.

As he had no money to make films, Kuleshov used a print of D.W. Griffith's Intolerance (1916) so that his students could re-edit scenes to change their literal and emotional meaning. He called this strategy, 'associational montage' and devised the Kuleshov Effect to demonstrate its power. By juxtaposing a close-up of actor Ivan Mozhuhkin with images of a bowl of soup, a child in a coffin, and a woman reclining on a sofa, Kuleshov could generate expressions of hunger, grief, and desire. His theories inspired Pudovkin to make such important pictures as Mother (1926), The End of St Petersburg (1927), and Storm Over Asia (1928). But it was Eisenstein who was to take the film world by storm.

1905 and All That

Several factors led to the 1905 Revolution, as the effects of recession and repression were exacerbated by defeats in the Russo-Japanese War. On 22 January 1905, Tsarist troops fired on the crowds outside the Winter Palace in St Petersburg and a wave of peasant protests and industrial disputes followed 'Bloody Sunday', culminating in a general strike. In June, the crew of the battleship, Prince Potemkin of Taurida, mutinied against conditions and the embattled Nicholas II was forced in October to accept the imposition of a constitutional assembly known as the Duma.

Keen to mark the 20th anniversary of events that had weakened the Romanov dynasty and presaged its collapse in October 1917, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee led by Anatoly Lunacharsky decided to commission a film commemorating what Lenin had called a 'dress rehearsal' for the overthrow of the monarchy. Impressed Eisentein's debut feature, Strike (1924), the committee appointed the 27 year-old as the director of the picture and set him to work on a screenplay with Nina Agadzhanova-Shutko, who had actively participated in the uprising.

As he had only just been released from his contract with the Proletkult Theatre, Eisenstein had hoped to adapt a couple of Civil War novels, Aleksandr Serafimov's The Iron Flood and Isaac Babel's The Red Cavalry, as his next projects. However, he recognised the honour being bestowed upon him and quickly came to enjoy collaborating with Agadzhanova-Shutko, who was able to make complex political ideas accessible to ordinary people. Things didn't always go smoothly, however, and in an effort to atone after a heated disagreement, Eisenstein bought his co-scenarist a live dove, only for it to get loose in her study and damage a chandelier and a bound collection of Lord Byron's poetry.

In one of his verses, dramatist Vladimir Mayakovsky had written: 'The cinema - purveyor of movement. The cinema - renewer of literature. The cinema - destroyer of aesthetics. The cinema - fearlessness. The cinema - a sportsman. The cinema - sower of ideas.' Eisenstein believed in the power of the moving image to win hearts and minds and wanted The Year 1905 to remind the audience that the revolution had been a nationwide affair. Assistant Grigori Alexandrov wrote: 'The original intention had been to make a film to be called 1905, with the purpose of showing many of the remarkable events of that early revolutionary year and Eisenstein was appointed director in March 1925...we had until 31 Decemher to finish it, or nine months from the day when Eisenstein and Nina Agadzhanova-Shutko first began work on the script. Nor should we forget that the film was originally intended to cover a great many incidents in 1905, and indeed the Potemkin affair was a tiny part of the original conception, occupying only two pages of the first scenario.'

In fact, the Odessa mutiny had only taken up half a page of the script, as Eisenstein had intended to devote it just 44 out of the film's planned 800 shots in order to cover the Russo-Japanese War, the Bloody Sunday massacre, the Moscow uprising, the October general strike, and the violence sparked by counter-revolutionaries. As he wrote to his mother, he was under enormous pressure to complete the filming in several cities in order to release the feature before the end of the anniversary year.

Alexandrov takes up the story: 'Shooting for 1905 began in the early spring, not in Odessa but in Leningrad...but the weather was bad, shootings delayed, and as every day brought us nearer to our dreaded deadline, we became more and more anxious. In the end we were advised by the Leningrad experts to go south for a time and work on another sequence for the film in the hope of returning to Leningrad when the weather improved. So we went to Odessa and set up our Headquarters in the Hotel London, where Eisenstein himself wrote the script of what eventually became Battleship Potemkin. We never went back to Leningrad.'

Eisenstein decided to work in Odessa because the weather was favourable and the local studios were well equipped. He would be able to get hold of a battleship from the Black Sea Fleet based in the port. Moreover, as the sequence was quite short, he hoped to be able to generate some momentum by wrapping quickly and moving on to the next location. Taken by Odessa, however, Eisenstein became more intrigued by its possibilities and decided to shift the focus of the film entirely on to the Potemkin mutiny and its consequences.

Up in Arms

Set in June 1905, Battleship Potemkin is divided into five acts and charts the events that provoked a mutiny aboard a pre-dreadnought vessel of the Imperial Russian Navy's Black Sea Fleet and its ramifications in the port city of Odessa.

Act I: Men and Maggots

Revolution has broken out in Russia and Potemkin crew members, Matyushenko (Mikhail Gomarov) and Vakulinchuk (Aleksandr Antonov), are discussing whether the ship's company should join the rebels. Retiring after their watch, the pair are woken when the duty officer (Aleksandr I. Levchin) searching the cabin stumbles and takes out his annoyance on a sailor (Ivan Bobrov) sleeping in his hammock. Angered by the outburst, Vakulinchuk addresses his shipmates: 'Comrades! The time has come when we too must speak out. Why wait? All of Russia has risen! Are we to be the last?'

The next morning, with the ship anchored off the island of Tendra, the crew complain about the quality of their rations. When they point to the maggots in the meat, Captain Golikov (Vladimir Barsky) summons the medical officer, who looks down his pince-nez and declares that the meat can easily be washed to remove the 'dead fly larvae'. Chief Officer Giliarovsky (Grigori Alexandrov) ushers the men away so that the cook can make some borscht.

Even he questions the safety of the meat and isn't surprised when the sailors refuse to eat the soup and have bread and some canned goods instead. While washing up, one of the men notices the words, 'Give Us This Day Our Daily Bread' inscribed on a plate and he smashes it on the deck in disgust.

Act II: Drama on the Deck

Deciding that those who refused to eat the borscht are guilty of insubordination at sea, Golikov orders the men on to fore-deck. He threatens to hang the culprits from the yardarm and officers and men alike look upwards and have ominous visions of shadowy corpses dangling in the breeze.

Matyushenko tells the men to break ranks and shelter under the gun turret. However, some are blocked from fleeing and Golikov calls out the guard to form a firing squad. He commands some petty officers to fetch a large tarpaulin and has it thrown over the quaking sailors. The Russian Orthodox priest taps his crucifix against his hand, as he gives a cursory blessing, but refuses to plead for mercy.

Despite the reluctance of some of the guards, the firing squad takes aim. But Vakulinchuk implores them to lower their rifles and his emboldened shipmates overpower Golikov and his officers. They are thrown into the sea, with the cowardly chaplain being hauled out of a hiding place and the doctor being mocked as he's branded worm food. The sailors celebrate their success. But it comes at a price, as Vakulinchuk is shot in the back of the head by Giliarovsky and becomes entangled in the rigging before falling into the sea.

Act III: A Dead Man Calls Out

When the Potemkin docks in Odessa, Vakulinchuk's corpse is taken to the quayside on a steamer and put on public display in a makeshift tent, with a sign reading, 'For a Spoonful of Borscht'. He's still there next morning, as the sun tries to break through the mist shrouding the port, as nothing stirs. But this merely is the quiet before the storm.

At first, a few individuals come to kneel beside the body, with some praying and others peeking out of curiosity. But word spreads and thousands are soon streaming towards the waterfront and lining the harbour wall to pay their respects. Inspired by the heroic sailor's sacrifice, the citizens start to protest against Nicholas II and his cruel regime. Hands that had been wringing handkerchiefs or clutching doffed caps turn to fists punching the air. A bourgeois rabblerouser (Glotov) tries to convince the crowd that the Jews are to blame rather than the Tsar. But he is shouted down and subjected to a beating.

A delegate from the shore boards Potemkin and gives a rousing speech proclaiming that the time has come for the people to seize power. As the crew members raise a red flag to pay tribute to their fallen comrade, they are cheered by the growing throng on the dock.

Act IV: The Odessa Steps

While some sail out to the Potemkin in small boats to show their solidarity with the sailors by giving them provisions, others gather at the Odessa Steps to wave to the ship. Smartly dressed ladies flirtatiously twirl their parasols, while mothers explain the situation to their children, who are excited to see the boats in the harbour. Students come to give their support, as does a man who has lost both his legs.

However, the disturbance has been reported to the authorities and a detachment of white-uniformed troops is lined up at the top of the flight, with fixed bayonets. On the order, they start to march relentlessly down the steps into a panicked crowd. As the boots pound on the stone steps, the soldiers are ordered to open fire on the retreating and unarmed citizens, who have no means of escape, as a Cossack unit has blocked off their retreat.

A mother (Propkopenko) loses hold of her son (A. Glauberman) and turns to see him being trampled underfoot after he is shot. She gathers him in her arms and walks up the steps to plead with the advancing soldiers to stop firing. But she is gunned down in cold blood, as is a woman wearing pince-nez (Nina Poltavseva), who is shot in the eye, while watching in horror as a mother (Beatrice Vitoldi) falls dead and sends her baby carriage bouncing down the steps. Its progress is halted by a Cossack wielding a sword.

Learning of the carnage, the crew aboard the Potemkin turn its guns on the opera house, which has become the headquarters of the officers co-ordinating the military response. They have been informed that a squadron loyal to the Romanovs is heading towards the Crimea to restore order. But shells crash into the theatre environs, as a trio of cuts between static shots of three stone lions suggests that the recumbent creature is rousing itself to roar.

Act V: One Against All

While their comrades sleep, the nightwatch scans the horizon for signs of the fleet. As dawn breaks, the decision is made to put to sea after a boisterous meeting of the entire crew. Lookouts remain in post, as the engine room becomes a hive of activity and shells are hauled to the deck in readiness for a skirmish.

When the ships are finally spotted, the order is given to go to action stations. The red flag is raised, along with the stark signal, 'Join Us!' Bracing themselves for action, the shipmates fix their gaze on the approaching warships. The cutting speed ramps up the tension before the lead vessel makes way for Potemkin and cheers of brotherhood ring out across the waves in a display of revolutionary unity, as the mutineers are allowed to proceed in safety.

Taking Steps

Filming on The Year 1905 started on 31 March 1925 in Leningrad. This was the setting for several scenes in the original scenario, including the railway strike and the crackdown on protest in Sadovaya Street. However, fog made it impossible to work outdoors and deteriorating weather conditions prompted Eisenstein to move south. One plus from the stalled start, however, was that the director realised he couldn't collaborate with cinematographer Aleksandr Levitsky and he replaced him with fellow Latvian, Eduard Tisse, with whom he would work for the rest of his career.

Equally important were assistant directors Grigori Aleksandrov, Mikhail Gomorov, Aleksandr Levshin, Aleksandr Antonov, and Maxim Strauch, whom Eisenstein nicknamed 'The Iron Five', as they never buckled under pressure. Aleksandrov was his closest confidante and he helped redraft the screenplay when Eisenstein decided to cut his losses and jettison the other seven episodes and focus on the Potemkin mutiny.

This meant ditching Agadzhanova–Shutko's screenplay and starting afresh. But Eisenstein was inspired by the events in Odessa and a walking tour after his arrival convinced him that he had found the perfect location. He was particularly excited by the Odessa Steps that he had first seen in the French magazine, L'Illustration, which had reported on the military crackdown in 1905. His notes also refer to a fascination with the way a cherry stone had bounced down a staircase and this happenstance seems to have inspired the famous baby carriage sequence.

The 120 steps would pass into screen history, although several other flights are shown in the film, as the citizens of Odessa come to pay their respects to Vakulinchuk. He was played by Antonov, while Alexandrov took on the role of Chief Officer Giliarovsky. But the majority of the actors not chosen from the Proletkult Theatre were cast for their physical features. This method was known as 'typage' and brought an authenticity to the revolutionary conceit of a 'collective hero' who could be readily identified with by audiences.

As Eisenstein explained: 'I do not pick my actors from the profession...They do not act roles. They simply are their natural selves. I get them to repeat before the camera just what they have done in reality. And in the mass action of my films, different as they are from each of other; they are significant not as separate human organisms, but as parts working together in a social organism, like the separate cells working together in the human body.'

He continued, 'A 30 year-old actor may be called upon to play an old man of 60. He may have a few days' or a few hours' rehearsal. But an old man will have had 60 years' rehearsal.' As a result, he was forever on the lookout for people who would fit roles, with the ship's doctor being a man spotted shovelling coal at a Sevastopol hotel, while the Orthodox priest was a gardener who had never acted in his life. No one seems to have bothered taking their names, however, as they have never been identified.

As there were so many extras to wrangle on the quayside and at the Odessa Steps, they were divided into groups to be supervised by Gomorov, Antonov, and Strauch, who all wore striped jumpers so that Eisenstein could spot them in the crowd. In order to make sure things ran smoothly during the precious daylight filming hours, the extras were rehearsed at night to ensure their blocking matched Eisenstein's meticulously composed images. He recognised the contribution of his cohorts in his later writings: 'What about the heroism of the five striped assistants?! The "iron five", taking all the abuse, shouting in all the dialects spoken by the crowd of 3000 extras who are unwilling to rush around "yet again" in the boiling sun.'

Eisenstein was also grateful for the full co-operation of the city authorities, who were used to working with the local studio, which offered some of the best facilities in the entire Soviet Union. Finding a suitable setting for the shipboard scenes proved more problematic, however. As the Potemkin had been decommissioned and was in the process of being dismantled, Eisenstein had to shoot on its sister ship, The Twelve Apostles. This had been abandoned in Sevastopol harbour when the White Russians fled the Crimea. Such was its position at anchor, however, that rocks were visible in the background and Tisse found it almost impossible to avoid them. At Eisenstein's request, the ship was rotated through 90° to give him a clear horizon. But his problems didn't end there.

The Twelve Apostles had been used as a mine store and it was decided that it would be too expensive and time-consuming to have the weapons removed before filming commenced. So, the extras playing the sailors were warned to move carefully about the deck, in case they caused any undue disturbance. The scenes at sea were filmed on the cruiser, Komintern, which was also used for the interiors involving the sleeping quarters and the galley.

Eisenstein had planned for the flotilla steaming towards the Potemkin to fire a volley of shots to add to the spectacle of the scene. One of the crew asked how he was going to ensure that each ship fired at the same time and he demonstrated how he would use a handkerchief to signal to the various vessels. Unfortunately, several skippers saw the waving hankie and mistook it for the genuine signal and loosed their guns. As the camera wasn't rolling, the moment was missed and Eisenstein was too embarrassed to ask the ships to reload.

Luckily, there were no such mishaps when it came to filming at the Odessa Steps. Jay Leyda described the scene in Kino: A History of the Russian and Soviet Film. 'Tisse's ingenuity,' he wrote, 'was ideal for Eisenstein's invention. The slaughter on the steps needed filming techniques as original as the new montage principles. A camera-trolley was built the length of the steps - dolly shots were then almost unknown in Russian films. Several cameras were deployed simultaneously. A hand-camera was strapped to the waist of a running, jumping, falling (and circus-trained) assistant.' With The Iron Five ensuring that everyone hit their marks, the precisely choreographed action was captured with impressive efficiency. But its brilliance only became apparent during the editing process.

Influenced by both the Marxist dialectic and Japanese pictographs, as well as by the theories he had learned from Kuleshov, Eisenstein's editorial style differed from that of contemporaries like Griffith and Pudovkin. While they linked images to create visually and rhythmically smooth sequences, Eisenstein had them collide in a manner that not only generated propulsive momentum, but also suggested associational meaning. His intention was to keep the audience involved in the action playing on the screen by jolting them into becoming active participants who completed the editorial schema by making their own connections and deriving their own meaning.

Clyde Kelly Dunagan puts it splendidly in his essay on Battleship Potemkin in The International Dictionary of Films and Filming: 'Eisenstein identified five methods of montage: metric, rhythmic, tonal, overtonal, and intellectual. Metric montage concerns conflict caused by the lengths of shots. Rhythmic montage concerns conflict generated by the rhythm of movement within shots. In tonal montage, shots are arranged according to the "tone" or "emotional sound" of the dominant attraction in the shots. In overtonal montage, the basis for joining shots is not merely the dominant attraction, but the totality of stimulation provided by that dominant attraction and all of its "overtones" and "undertones": overtonal montage is, then, a synthesis of metric, rhythmic, and tonal montage, appearing not at the level of the individual frame, but only at the level of the projected film. Finally, intellectual montage involves the juxtaposition of images to create a visual metaphor.'

Simple really (ahem) and all five kinds of montage can be seen in the Odessa Steps sequence, with metric and rhythmic montage dictating the growing sense of dread as the marching soldiers come closer to the fleeing civilians. Tonal montage can be detected in the way Eisenstein and Tisse use light and shade to intensify the atmosphere, such as when the shadows of the gun-wielding troops fall across the mother holding her dying child. Overtonal montage is evident in the interplay between the metric, rhythmic, and tonal elements, while the use of intellectual montage is encapsulated by the metaphorical effect caused by the shots of the three stone lions.

By contrasting images of innocence and violence, Eisenstein conveys the contrasting mindsets of the soldiers and the bystanders. He also shapes the viewer's reaction to the imagery by using long and medium shots of the troops to depersonalise them and close-ups of the victims to individualise them and make them more empathetic. Low and overhead angles are similarly employed to juxtapose the humanity of the masses and the inhumanity of the Tsarist machine.

No one had done anything like this before. In all, the Odessa Steps sequence lasts for six minutes and includes 158 separate shots and three intertitle cards. The shortest shots last just six frames, while the longest (showing the mother mounting the steps with her son) runs for 217 frames. There was nothing accidental about the construction of the sequence or what it was striving to communicate. As Eisenstein wrote in the introduction to the 1926 published screenplay, 'movement - is used to express mounting emotional intensity. First, there are close-ups of human figures rushing chaotically. Then, long-shots of the same scene. The chaotic movement is next superseded by shots showing the fret of soldiers as they march rhythmically down the steps. Tempo increases. Rhythm increases. And then, as the downward movement reaches its culmination, the movement is suddenly reversed: instead of the headlong rush of the crowd down the steps we see the solitary figure of a mother carrying her dead son, slowly and solemnly going up the steps.'

The average 90-minute feature in 1925 contained about 600 shots. By contrast, Battleship Potemkin crammed 1346 shots into its 81 minutes and not one edit point was wasted. It was taxing and exhausting work, as Alexandrov later recalled: 'The film which lasts for nearly an hour and a quarter at its original length was edited in less than a fortnight by Eisenstein and an assistant, working day and night and hardly ever leaving the cutting-room...I remember that we spent most of the final days with the man who helped us arrange the titles (Sergei Tretyakov). We were still working on this on the night of the first screening, which was in the Bolshoi Theatre, and I spent the evening riding a motorcycle between the cutting-room and the theatre, carrying the reels one at a time.' Now that's cutting it fine!

A Shock to the System

The Bolshoi screening that Alexandrov mentioned took place on 21 December 1925 before a specially invited audience of Party members, activists, and intellectuals. As the film was shown using a single projector, applause broke out during the four reel changes, while the appearance of the handtinted red flag provoked clapping and cheering.

The formal premiere was held at the 1st Goskinoteatre in Moscow on 18 January 1926. However, the version shown that night no longer exists. Eisenstein's print ran for 86 minutes, but Cinema Paradiso users will have to be content with a 74-minute edit. This is partly down to the fact that handcranked cameras and projectors worked at 16 frames per second, whereas modern equipment operates at 24fps. However, cuts were made shortly after the premiere to reflect the changing power dynamics within the Kremlin. Eisenstein had introduced the action with a quotation from Leon Trotsky, which read: 'The spirit of mutiny swept the land. A tremendous, mysterious process was taking place in countless hearts: the individual personality became dissolved in the mass, and the mass itself became dissolved in the revolutionary impetus.'

Following the death of Lenin in January 1924, however, there had been a battle for power between Trotsky and Joseph Stalin, which the Georgian had won. As Trotsky's position became more precarious, it was deemed expedient to remove the quote for fear of upsetting Stalin. Eventually, lines from Lenin's Revolutionary Days were inserted to read, 'Revolution is war. Of all the wars known in history, it is the only legitimate, rightful, just and truly great war… In Russia, this war has been declared and won.' But the censor also had their say and the odd image was trimmed in order to comply with Party demands. This frustrated Eisenstein, as he had made the picture for the masses and wanted them to unite in sharing the emotions of the Odessans and the revolutionary zeal that they had fostered.

There were also members of the art intelligentsia who felt that montage was an affectation and some accused Eisenstein of formalism - in other words placing greater emphasis on the aesthetic aspect of a work than its ideological content. Such negativity made distributors Sovkino nervous and it kept the only existing print in its vault. Eisenstein was dismayed that a film he felt broke new ground on many levels was being dismissed as a failure.

As good friend Nikolai Aseev had contributed to the intertitles, poet Vladimir Mayakovsky took up the film's cause with Sovkino's president, Konstantin Shvedchikov. He was a politician whose influence had waned after the death of his close ally, Lenin, and Mayakovsky reminded him that he would be harshly judged if he opposed the export of Battleship Potemkin so that foreign audiences could appreciate the ingenuity and potency of Soviet cinema. 'Shvedchikovs come and go,' he concluded, 'but art remains. Remember that!'

His exhortations worked and the film was screened in Berlin in 1926, where it was seen by Hollywood icons Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford. The former later opined, 'The Battleship Potemkin was the most profound emotional experience of my life.' So, when the couple visited Moscow in July 1926, they offered to help the film secure a distribution deal in the United States and invited Eisenstein to Los Angeles. On his return home, Fairbanks arranged for a number of private viewings. According to legend, Gloria Swanson hosted one screening at which the images were projected on to one of her satin bedsheets.

Producer David O. Selznick was so blown away that he reported to boss Harry Rapf at MGM in a memo dated 15 October: 'It was my privilege a few months ago to be present at two private screenings of what is unquestionably one of the greatest motion pictures ever made...I therefore suggest that it might be advantageous to have the organisation view it in the same way that a group of artists might view and study a Rubens or a Raphael.' He declared the film to be 'gripping beyond words' and praised it for possessing 'a technique entirely new to the screen'. Selznick concluded that the front office 'might well consider securing the man responsible for it'.

Eventually, Potemkin premiered at the Biltmore Theatre in New York on 5 December 1926. But screenings were limited because the film's heroes were mutineers and revolutionaries who offered 'American sailors a blueprint as to how to conduct a mutiny'. Weimar Germany had similar fears and kept the film away for several months. But, in March 1926, after director Phil Jutzi has produced a new cut, the Berlin Censorship Committee passed Potemkin, albeit minus footage of the officers being thrown overboard.

Esteemed theatre director Max Reinhardt confessed that 'after viewing Potemkin, I am willing to admit that the stage will have to give way to the cinema', while the critic for the Berliner Tageblatt insisted, 'Eisenstein has created the most powerful and artistic film in the whole world.' Nevertheless, the German High Command put patrols outside cinemas in garrison towns to keep military personnel away. Yet, when Joseph Goebbels became the Third Reich's Minister of Propaganda, he told the leaders of the German film industry, 'This is a marvellous film without equal in the cinema. Anyone who bad no firm political conviction could become a Bolshevik after seeing the film.' Eisenstein was appalled, however, when Goebbels advised German directors to 'use Potemkin as a model of truthful art'. Indeed, he wrote Goebbels an open letter, in which he averred that 'truth and National Socialism cannot be reconciled. He who is for truth cannot line up with National Socialism. He who is for truth is against you!…How do you dare, anyway, to talk about life? You, who are bringing death and banishment to everything good in your country by the executioner's axe and the machine gun!'

Notwithstanding this attack and Heinrich Himmler's decision to bar SS members from attending screenings, Goebbels continued to push for 'a National Socialist Potemkin'. Finally, during the Second World War, he got to sanction a film with its own Odessa Steps sequence, Hans Steinhoff's Ohm Krüger (1941).

France and Japan proved more resistant. The British Board of Film Censors was also less accommodating in banning Potemkin in 1926 for being 'Bolshevik propaganda'. However, the London Film Society hosted a screening in 1929 that drew a large crowd that contained some influential figures within the British film industry. Another quarter century was to pass before the BBFC passed the film for exhibition, with an X certificate that remained in force until 1987.

With national censors taking exception to different scenes, as many as seven versions of Potemkin were in circulation in Europe during the 1930s. Ironically, the German edit was the best preserved and closest to Eisenstein's original vision and this was the one that most people saw until a process of restoration was undertaken in the early 2000s.

A Century of Incalculable Inspiration

Despite being seen by comparatively small audiences at film societies or political meetings, Battleship Potemkin quickly became one of the most talked-about films of the 1920s. The first Russian audiences watched it with an improvised piano score, but the German distributor was unhappy with the accompaniment and hired Austrian composer Edmund Meisel to write a new score, giving him just 12 days before the Berlin premiere on 29 April 1926. Unusually for the time, he reflected the precise action on the screen rather than providing a melodic backdrop and Eisenstein was so impressed that he asked Meisel to compose the score for October (1927).

He also retained Meisel's contribution when a dubbed dialogue version was released on the 'Nadelton' sound-on-disc process in 1930. Indeed, Meisel also devised a machine to create sound effects to complement the music and the dialogue, which was scripted by A.J. Lippl and was delivered in a staccato manner to reflect the pulsating montage in about 50% of the scenes. The sonorised version premiered at the Marmorhaus cinema in Berlin on 12 August 1930 and did brisk business. But no other language versions appear to have been made and the German edit was shelved once the Nazis took power.

The recent rediscovery of these long-lost discs means we can hear Meisel's arrangement for the first time, as parts of his manuscript had gone missing before the complete piano score was unearthed in 1983. Eisenstein had hoped to reissue Potemkin every 20 years with a new score to reflect changing tastes. But he died two years before Nikolai Kryukov completed his 1950 interpretation, which was followed by a Dmitri Shostakovich compilation score in 1976. These and variations on the Meisel music were based on the censored German print and it's only recently that Meisel's work has been adapted to fit the 2005 restored print. However, contemporary composers are still being drawn to the film. In the mid-1980s, Chris Jarrett and Eric Allaman respectively composed piano and electronic scores, while Pet Shop Boys, Neil Tennant and Chris Lowe, debuted their own version in 2004.

Michael Nyman premiered his own score in 2011. He, of course, was a regular collaborator with Peter Greenaway, who had planned to follow the Mexico-based Eisenstein in Guanajato (2015) with The Eisenstein Handshake, which was to have been set in Switzerland. Also known as The Swiss Hoax, this was to have explored a trip that Eisenstein, Alexandrov, and Tisse had made to the world's first film festival in 1929, when they shot the first two pictures made in Switzerland, Misery and Fortune of Woman and The Storm Over La Sarraz. Sadly, the project announced in 2014 was never realised. Nor was the plan to make 100 short films about the famous people met Eisenstein on his travels in Europe and America. This is a great shame, as they include such notables as Albert Einstein, Pablo Picasso, Sigmund Freud, Jean Cocteau, Filippo Marinetti, James Joyce, Bertolt Brecht. Gertrude Stein, Käthe Kollwitz, Erich von Stroheim, Josef von Sternberg, Ava Gardner, Walt Disney, Mickey Mouse, and Rin Tin Tin.

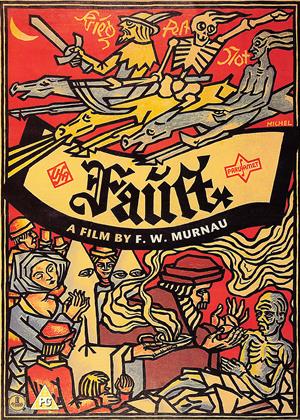

Soon after Potemkin's release, Eisenstein was dispatched to Paris and Berlin to learn about modern techniques, so that the entire Soviet film industry could benefit from them. He met F.W. Murnau and Emil Jannings on the set of Faust (1925) and Fritz Lang and screenwriter wife Thea von Harbou while they were working on Metropolis (1927). Both features are available to rent from Cinema Paradiso, which has a fair few silent classics to discover. As we approach the centenary of talking pictures in 2027, we should never forget that cinema is a visual medium or that many of the stylistic and editorial gambits that we now take for granted originated during the medium's first three decades.

Directors as different as Charlie Chaplin, Orson Welles, Billy Wilder, Michael Mann, and Paul Greengrass have chosen Potemkin among their favourite films. In 1952, critics voting in Sight and Sound's inaugural decennial poll placed Battleship Potemkin in fourth place, ahead of David Lean's Brief Encounter, Carl Theodor Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), Marcel Carné's Le Jour se lève (1939), Erich von Stroheim's Greed (1924), Robert Flaherty's Louisiana Story (1948), and D.W. Griffith's Intolerance (1916). However, it trailed behind Charlie Chaplin's The Gold Rush (1925) and City Lights (1931), and Vittorio De Sica's Bicycle Thieves (1948). Six years later, those canvassed at the 1958 Brussels World's Fair placed the following in reverse order: Aleksandr Dovzhenko's Earth (1930), Orson Welles's Citizen Kane (1941), Vsevelod Pudovkin's Mother (1927), Intolerance, Greed, Jean Renoir's La Grande illusion (1937), The Passion of Joan of Arc, Bicycle Thieves, The Gold Rush, and Potemkin.

It's fascinating that so many silent films remained in the pantheon three decades after the advent of sound. But this was Potemkin's polling high point, as it slipped to joint sixth in 1962, along with Bicycle Thieves and Eisenstein's own Ivan the Terrible: Part 1 (1944). It rose back to third in 1972 before dropping back to sixth a decade later, a position it shared in 1992 with The Passion of Joan of Arc, Jean Vigo's L'Atalante (1934), and Satyajit Ray's Pather Panchali (1955). Having dipped a place to share seventh spot with F.W. Murnau's Sunrise (1927), however, Potemkin lost its Top 10 berth by sliding to eleventh in 2012 before plummeting to 54th in 2022.

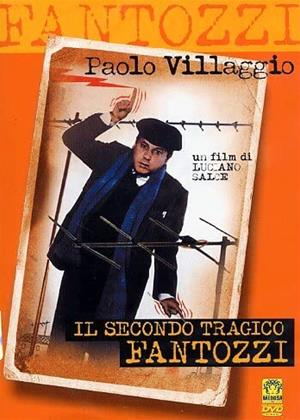

While the technique of montage has influenced scenes such as the shower stabbing in Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho (1960), the climactic shootout in Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde (1967), and the gun battle in Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch (1969), the Odessa Steps sequence that has been much imitated in recent times. Its influence can be most readily seen in the adverts playing in any commercial break on television. But among the pictures paying homage or extracting the Mikhail are Joseph McGrath's The Magic Christian (1969), Woody Allen's Bananas (1971) and Love and Death (1975), Ettore Scola's We All Loved Each Other So Much (1974), Luciano Salce's Il secondo tragico Fantozzi (1976), Terry Gilliam's Brazil (1985), Chandrashekhar Narvekar's Tezaab (1988), Juliusz Machulski's Déjà Vu (1989), Christian de Chalonge's The Children Thief (1991), Larry Latham's An American Tail: The Mystery of the Night Monster (1999), Anno Saul's Kebab Connection (2004), George Lucas's Star Wars: Episode III - Revenge of the Sith (2005), Shuko Murase's Ergo Proxy (2006), Jacob Tierney's The Trotsky (2009), Johnnie To's Three (2016), and Denis Villeneuve's Dune (2021).

The most famous citation, however, comes in Brian De Palma's The Untouchables (1987), which sees a baby carriage get caught up in a shootout at Chicago's Union Station, Indeed, it's this scene rather than the one in Potemkin that Peter Segal parodied in the opening scene of Naked Gun 33?: The Final Insult (1994), which lands Frank Drebin (Leslie Nielsen) with four prams, a president, a pope, and a lawnmower. Even Homer Simpson got in on the act in the 'G-G-Ghost D-D-Dad' segment of the 2000 'Treehouse of Horror XI' episode of The Simpsons (1989).

Such was the importance of Battleship Potemkin that attempts were periodically made to piece together the original edit. As European archives became more organised, scholars started poring over catalogues to establish how many variations existed and how they differed from each other. In 1976, Naum Kleiman began work on Eisenstein's intended running order and, a decade later, Enno Patalas started assembling the missing scenes to reinsert them into the 1926 German print. Restoring and reassembling all 1374 shots took some doing, however, and it wasn't until 2005 that the Deutsche Kinemathek could premiere the picture at the Berlin Film Festival, complete with Trotsky's opening quotation.

History can't be rewritten so easily, however. Joseph Stalin so distrusted Eisenstein that he sought not just to restrict his creative freedom, but also to control his subject matter. Projects including The General Line (aka The Old and the New, 1929), ¡Que viva México! (1930-31), and Bezhin Meadow (1937) were left unfinished and Eisenstein only completed Alexander Nevsky (1938) and Ivan the Terrible before his death at the age of 50. Indeed, Ivan the Terrible, Part Two: The Boyars' Plot (1946) was withheld until 1958 and he was prevented from embarking upon Part Three, even though the screenplay had been completed.

Nevertheless, Eisenstein left behind some of the most insightful theoretical writing on film and art and passed on his wisdom via the classroom. Moreover, he has inspired generations of film-makers by challenging them to make each image count in order to engage the audience and make viewing an intellectually and emotionally proactive and rewarding experience.

-

The Fall of the Romanov Dynasty (1927) aka: Padenie dinastii Romanovykh

1h 27min1h 27min

1h 27min1h 27minEsfir Shub took the compilation documentary to new levels with this account of the Russian Revolution. As much a work of detection as depiction, she viewed 60,000 metres of footage from across the continent, including the neglected archive of Nicholas II, who was the most-filmed monarch of the age. The juxtaposition of his luxurious lifestyle with the poverty of his subjects made this a potent 10th anniversary commemoration of his overthrow.

- Director:

- Esfir Shub

- Cast:

- Mikhail Alekseyev, Alexei Brusilov, Nikolai Chkheidze

- Genre:

- Documentary, Special Interest, Children & Family

- Formats:

-

-

Laurel and Hardy: A Job to Do (1933)

3h 28min3h 28min

3h 28min3h 28minThe Music Box (1932). Available from Cinema Paradiso on Laurel and Hardy: A Job to Do (2019), this Oscar-winning gem stars its own flight of steps. Stan and Ollie had to lug a crated player piano up all 133 steps linking Vendome Street with Descanso Drive in the Silver Lake district of Los Angeles. A plaque marks the spot, but visitors will search in vain for 1127 Walnut Avenue.

- Director:

- Not Available

- Cast:

- Stan Laurel, Oliver Hardy

- Genre:

- Classics, Comedy

- Formats:

-

-

Mutiny on the Bounty (1935)

Play trailer2h 7minPlay trailer2h 7min

Play trailer2h 7minPlay trailer2h 7minThis is the first of three features recalling the mutiny led against Captain William Bligh by Fletcher Christian on 28 April 1789. Charles Laughton and Clark Gable were directed by Scotsman Frank Lloyd, who meticulously researched the period and offered uncredited bit parts to David Niven and his good friend, James Cagney, who happened to be sailing his boat near Lloyd's location on Catalina Island.

- Director:

- Frank Lloyd

- Cast:

- Charles Laughton, Clark Gable, Franchot Tone

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics, Action & Adventure

- Formats:

-

-

San Demetrio, London (1943)

1h 34min1h 34min

1h 34min1h 34minThe crew of the Potemkin sought asylum in Romania after being denied safe harbour in the Crimea. None of the mutineers featured in Eisenstein's film, but chief engineer Charles Pollard (who is played by Walter Fitzgerald) and some of his shipmates joined the Ealing cast of Charles Frend's recreation of an eponymous tanker's mid-Atlantic encounter with the German pocket battleship, Admiral Graf Spee.

- Director:

- Charles Frend

- Cast:

- Arthur Young, Walter Fitzgerald, Ralph Michael

- Genre:

- Action & Adventure, Drama, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

Doctor at Sea (1955) aka: Doktor Ahoi!

Play trailer1h 29minPlay trailer1h 29min

Play trailer1h 29minPlay trailer1h 29minThere are no maggots in the meat aboard SS Lotus, but there is plenty to keep Captain Wentworth Hogg (James Robertson Justice) on his toes, as the daughter of his shipping line (Brenda De Banzie) is on the lookout for a husband. This was the second of Dirk Bogarde's three outings as Dr Simon Sparrow and his travelling companion was Brigitte Bardot making her English-language debut.

- Director:

- Ralph Thomas

- Cast:

- Dirk Bogarde, Brenda De Banzie, Brigitte Bardot

- Genre:

- Classics, Comedy

- Formats:

-

-

The Odessa File (1974) aka: The O.D.E.S.S.A. File

Play trailer2h 3minPlay trailer2h 3min

Play trailer2h 3minPlay trailer2h 3minDespite the title, Ronald Neame's adaptation of Frederick Forsyth's bestselling thriller centres on a secret cadre of former SS members, who are plotting against Israel with Egyptian agents. However, a West German journalist has stumbled upon a file giving details of war criminals who have achieved high office by burying the facts about their murderous past,

- Director:

- Ronald Neame

- Cast:

- Jon Voight., Cyril Shaps, Maximilian Schell

- Genre:

- Thrillers, Drama, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

Naked Gun 33 1/3: The Final Insult (1994)

Play trailer1h 19minPlay trailer1h 19min

Play trailer1h 19minPlay trailer1h 19minWoken from his Potemkin-style nightmare, Frank Drebin (Leslie Nielsen) struggles to cope with life after Police Squad. But he's lured undercover by Ed (George Kennedy) and Nordberg (O.J. Simpson, in his final film), who need help finding a bomber who is planning to attack the Academy Awards.

- Director:

- Peter Segal

- Cast:

- Leslie Nielsen, Priscilla Presley, George Kennedy

- Genre:

- Comedy

- Formats:

-

-

Battleship Potemkin/Drifters (1929) aka: Bronenosets Potyomkin/Drifters

1h 50min1h 50min

1h 50min1h 50minThe restored version of Sergei Eisenstein's masterpiece is accompanied by Edward Meisel's 1926 score on this BFI disc, which also contains Drifters, a 1929 short by John Grierson that reveals how much montage influenced the father of the British documentary movement and the extent to which its influence can still be felt today in social realist cinema.

- Director:

- Sergei Eisenstein

- Cast:

- Grigori Alexandrov, Vladimir Barsky, Aleksandr Antonov

- Genre:

- Drama, Documentary, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

The Death of Stalin (2017)

Play trailer1h 42minPlay trailer1h 42min

Play trailer1h 42minPlay trailer1h 42minStalin outlived Eisenstein by five years and the sense of how his Politburo responded to his passing with a mixture of relief, sorrow, and sheer terror is brilliantly captured in Armando Iannucci's satire. The ensemble playing is impeccable, but Steve Buscemi and Simon Russell Beale excel, as Nikita Khrushchev and Lavrenti Beria jostle for power.

- Director:

- Armando Iannucci

- Cast:

- Steve Buscemi, Simon Russell Beale, Jeffrey Tambor

- Genre:

- Comedy

- Formats:

-

-

My Imaginary Country (2022) aka: Mi país imaginario

Play trailer1h 22minPlay trailer1h 22min

Play trailer1h 22minPlay trailer1h 22minSparked by a rise in train fares, a wave of protests across Chile culminated in 1.2 million people marching to Santiago's Plaza Baquedano on 25 October 2019. As on the Odessa Steps, a woman was hit in the eye and photographer Nicole Kramm describes her experience in Patricio Guzmán's hard-hitting documentary.

- Director:

- Patricio Guzmán

- Cast:

- Not Available

- Genre:

- Documentary, Special Interest

- Formats:

-