Eighty years ago in June, Britain found itself alone against the might and fury of the Third Reich. German tanks had attacked Holland and Belgium on 10 May and France fell on 22 June, just 18 days after the last Allied troops had been evacuated from the beach at Dunkirk. With the continent under Nazi control, the focus of the war switched to the Atlantic Ocean before the United States joined the conflict in December 1941. Thousands of service personnel on each side were taken prisoner during the ensuing encounters in North Africa and Europe and Cinema Paradiso reflects on these aspects of the conflict in its latest survey of the films depicting the Second World War.

Operation Dynamo remains one of the most desperate rearguard actions in British military history. Between 26 May and 4 June 1940, dozens of ships and hundreds of commercial and leisure craft ferried 338,226 stranded souls across the English Channel. As narrator Laurence Olivier makes clear in the 'France Falls - May-June 1940' episode of The World At War (1973-74), this was anything but a glorious victory. But the nation took pride in its resolve and resourcefulness, as is revealed in The Little Ships of England (1943), a documentary short that can be found on the excellent BFI collection, Tales From the Shipyard (2010).

Hollywood also recognised the magnitude of the sacrifice and Kent resident Clem Miniver (Walter Pidgeon) set sail for France in his motorboat, The Starling, in William Wyler's Mrs Miniver (1942), a flag-waving adaptation of the Times newspaper column written by Jan Struther that won six Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Director Actress and Supporting Actress for Greer Garson and Teresa Wright. Although the evacuation was mentioned in numerous dramas about the war, including Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), it wasn't until 1958 that the mechanics of the mission were outlined in Leslie Norman's Dunkirk. With a script based on eyewitness accounts, this was the last war film produced by Ealing Studios and it gave equal weight to errors of judgement and acts of heroism, as John Mills tries to lead a bedraggled unit of the British Expeditionary Force to safety.

Several documentaries have been made about the operation, with Escape From Dunkirk (2001), Dunkirk: Battle For France (2002), I Was There: True Stories of Dunkirk (2004), The Road to Dunkirk, The Dunkirk Story (both 2010), and Last Boat From Dunkirk (2012) all being available from Cinema Paradiso. The emphasis was squarely back on the miraculous nature of the enterprise in Alex Holmes's Dunkirk (2004), Nick Lyon's Operation Dunkirk and Christopher Nolan's Dunkirk (both 2017), which set new standards for the combat picture with an imposing epic that received eight Oscar nominations.

Dynamo also features prominently in both Joe Wright's adaptation of Ian McEwan's Booker-shortlisted bestseller, Atonement (2007), and Their Finest (2016), Lone Scherfig's account of the British film industry's bid to sustain the nation's morale, while also seeking to convince America to join the fight against the Axis. Moreover, the evacuation gave Winston Churchill the chance to establish his credentials as a wartime leader, having succeeded Neville Chamberlain on 10 May, following the events depicted in Richard Loncraine's The Gathering Storm (2002) and Thaddeus O'Sullivan's Into the Storm (2009). His famous 'fight on the beaches' speech was inspired by Dunkirk and it is delivered with growling potency by the Oscar-winning Gary Oldman in Joe Wright's Darkest Hour (2017).

The Senior Service

From the moment France surrendered, Britain knew that Adolf Hitler would start making preparations to invade. As consequence, the country became increasingly reliant on transatlantic trade in its efforts to defend itself and the Royal Navy was detailed to support the mercantile marine by escorting shipping through the sea lanes that were being targeted by Germany's Kriegsmarine. Ealing Studios boss Michael Balcon was keen to highlight this important work and commissioned Pen Tennyson to direct Convoy (1940), which stars Clive Brook as a captain who discovers that new first officer John Clements is romancing his wife, Judy Campbell. Despite the melodramatic narrative, Tennyson (who was the great-grandson of poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson) adopts a docurealistic approach to ensure the authenticity of action he had witnessed at first hand by joining the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve during pre-production. Sadly, this would prove to be the twentysomething's final film, as he was killed in a plane crash while heading to a shoot at Scarpa Flow in July 1941.

Around this time, Britain started receiving goods from the United States under the Lend-Lease scheme. However, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had to uphold the policy of Isolationism that the US had pursued after Woodrow Wilson had failed to persuade Congress to support the League of Nations that he had launched after the Great War. But Hollywood was careful not to take sides during the first two years of the Second World War in case it offended the pro-Axis parts of the immigrant population.

It was only after the Japanese attack on the Hawaiian naval base at Pearl Harbor in December 1941 that the studios began to produce anti-Nazi features. Humphrey Bogart cut a not so commanding figure that resulted in being nominated for Best Actor as Captain Queeg in Edward Dmytryk's The Caine Mutiny (1954). Swapping a six-shooter for a telescope, Randolph Scott gives one of the best performance of his career as a Canadian skipper running the gauntlet in Robert Rosson's Corvette K-225 (1943), which included scenes directed by Hollywood's grittiest man of action, Howard Hawks. But the most memorable mid-Atlantic picture produced in Hollywood during the war was Alfred Hitchcock's Lifeboat (1944), which was based on an Oscar-nominated John Steinbeck short story and centres on the survivors of a U-boat attack as they await rescue with a dastardly Nazi in their midst.

Hitchcock would also receive an Oscar nomination for the brilliant manner in which he wrought suspense from action contained within a confined space. An aquatic tank was also required for the bookending sequences in Noël Coward and David Lean's In Which We Serve (1942), which opens with the surviving crew members of HMS Torrin clinging to a Carley float and thinking back on events that were inspired by Lord Louis Mountbatten's experiences aboard HMS Kelly prior to the Battle of Crete in May 1941. Having missed out on Best Picture to Michael Curtiz's Casablanca (1942), Coward accepted an Honorary Academy Award for his achievement as writer, actor and director.

This much-lauded saga was more traditional in form than the period's other studies of the war at sea. Charles Frend put a realist spin on the abandoned ship storyline in San Demetrio, London (1943), which was notable for the casting of actual seamen in a reconstruction of their efforts to regain control of a burning ship carrying 12,000 tonnes of aviation fuel. Following the docufiction example, Pat Jackson's Western Approaches (1944) also takes place in a lifeboat, as the 22-man crew of a sunken vessel realise that their Morse signal has been picked up by a U-boat, as well as the ship coming to rescue them.

Filmed in Technicolor off the Irish coast, this Crown Film Unit tribute to the Merchant Navy rather stands in glorious isolation, as the majority of British maritime films focus on the Royal Navy's titanic struggle with the German fleet. Prized trophies like the battleships Tirpitz and Bismarck and the cruiser Graf Spee were reclaimed in such patriotic postwar pictures as Ralph Thomas's Above Us the Waves (1955), Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's The Battle of the River Plate (1956) and Lewis Gilbert's Sink the Bismarck! (1960). Daring operations were also fictionalised to suit the storyline, as with Compton Bennett's Gift Horse (1952), which drew on the St Nazaire Raid of March 1942 for its account of skipper Trevor Howard's efforts to make do with a rusty old tub donated by the Americans and redubbed HMS Ballantrae.

Despite having personally been invalided out of the war with mental health issues, Howard became a war movie stalwart and he's on duty again as a Marine captain heading off on a special mission with actor-director José Ferrer to kayak into an occupied French port and blow up some German battleships in The Cockleshell Heroes (1955), which recalls the infiltration of Bordeaux harbour during Operation Frankton in December 1942. The source of the action in Ronald Neame's The Man Who Never Was (1956), was Operation Mincemeat, which was dreamed up by naval intelligence officers Clifton Webb and Robert Flemyng in order to dupe the Germans into thinking that the Allies were plotting to invade Greece rather than Sicily.

Nigel Balchin's script relied on the memoirs of Lieutenant Commander Ewen Montagu and the printed word also proved pivotal to a number of fondly remembered features, including Charles Frend's The Cruel Sea (1953), which follows the exploits of Lieutenant Commander Jack Hawkins aboard the corvette HMS Compass Rose and the frigate HMS Saltash Castle in Eric Ambler's deft interpretation of Nicholas Monsarrat's fact-based bestseller. CS Forester's Brown on Resolution was similarly reworked to star Jeffrey Hunter and Michael Rennie in a salute to the Mediterranean fleet in Roy Boulting's Sailor of the King (1953), while John Harris's novel was tailored for Michael Redgrave and Dirk Bogarde in Lewis Gilbert's The Sea Shall Not Have Them (1954), which centres on the heroics of the RAF's Air Sea Rescue Service.

Little-known novelist Edmund Gilligan provides the inspiration for Alfred L. Werker's Sealed Cargo (1951), which sees trawler skipper Dana Andrews come to question the wisdom of using his boat, the Daniel Webster, to give Dane Claude Rains a tow when he is deserted by his crew after their four-rigged sailing ship is torpedoed off the Newfoundland coast. In 1958, Jan De Hartog's novel, Stella, was rejigged for Carol Reed's The Key, which teamed Sophia Loren, William Holden and a BAFTA-winning Trevor Howard in a drama set in wartime Dorset that turns on the travails of a Swiss expatriate mourning the death of her tugboat skipper lover.

Gibraltar provides the setting for William Fairchild's The Silent Enemy (1958), another study of a lesser-covered aspect of the war that derives from Marshall Pugh's Commander Crabb and stars Laurence Harvey as a frogman seeking to stop the Italian 10th Flotilla. Bernhard Wicki's Morituri (1965) stars Marlon Brando as a German pacifist who is blackmailed by Trevor Howard into impersonating an SS officer in order to scuttle Yul Brynner's merchant ship.

Up Periscope

Emeric Pressburger settled for a writing brief on Michael Powell's 49th Parallel (1941) which controversially took the viewpoint of Eric Portman and his fellow submariners after their U-boat is sunk in Hudson's Bay by the Royal Canadian Air Force and they are forced to seek shelter inland. Laurence Olivier, Leslie Howard and Raymond Massey lead a stellar ensemble that includes Anton Walbrook, who donated half of his fee to the Red Cross.

As the war raged across the Atlantic, four notable features were made about submarines in 1943. Vernon Sewell's The Silver Fleet (1943) stars Ralph Richardson as a Dutch shipbuilder, who is branded a collaborator when Reich commander Esmond Knight orders him to switch production to U-boats. There's no danger of John Mills being identified as anything but a hero, however, as he takes command of HMS Sea Tiger in Anthony Asquith's We Dive At Dawn (1943) and heads into the Baltic to try and keep the new Nazi battleship, Brandenberg, penned in the Kiel Canal.

Having joined the Allied cause, Hollywood turned its ire on the U-boats attacking transatlantic shipping and Archie Mayo's Crash Dive became the first submarine movie to win an Academy Award when it was commended for the special visual effects used to show how romantic rivals Tyrone Power and Dana Andrews are forced to work together when the USS Corsair discovers that a German tanker is actually a Q-ship supplying a secret base. Duplicity is also uncovered by FBI agent Wendy Barrie in Frank McDonald's Submarine Alert (both 1943), as German and Japanese agents use radio signals to co-ordinate attacks around the US coastline.

After the war, crooner Dick Powell did a magnificent job of directing The Enemy Below (1957), which draws on a novel by Denys Rayner for its cat-and-mouse game in the South Atlantic between U-boat captain Curd Jürgens and Robert Mitchum, who commands the destroyer escort vessel USS Haynes.

Military historians will recognise that Operation Source, which saw the Tirpitz sunk in a Norwegian fjord by a clutch of British mini-subs, provides the plotline for William A. Graham's Submarine X-1 (1968), which follows Canadian diving expert James Caan as he prepares for a tilt at the disabled German battleship, Lindendorf. Peter O'Toole proves even more gung-ho in Peter Yates's take in Max Catto's novel, Murphy's War (1971), as he discovers a disused plane while recovering in Sian Phillips's Venezuelan missionary sanctuary and vows vengeance on the U-boat that had sunk his merchant ship, The Mount Kyle.

However, the emphasis is solely on the Grey Wolves under the command of U-96 skipper Jürgen Prochnow in Wolfgang Petersen's Das Boot (1981). The original feature adaptation of Lothar-Günther Buchheim's classic 1973 novel ran for 200 minutes and was nominated for six Academy Awards, including Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay. But Petersen's 1985 mini-series of the same name expanded the unbelievably visceral and tense action to 282 minutes. Even this pales beside the 465 minutes in Andreas Prochaska's sequel, Das Boot (2018), however, which picks up the story nine months later and draws on Buchheim's 1995 tome, Die Festung, to juxtapose events inside the U-612 and the growing resistance mounting in the French port of La Rochelle.

Another Unterseeboot provides the title for Jonathan Mostow's U-571 (2000), although this account of the joust between German skipper Thomas Kretschmann and S-33 captain Bill Paxton and his ambitious second, Matthew McConaughey, was condemned by British historians for claiming that an American submarine had captured the first Nazi encoding device when the British had retrieved an Enigma machine before the Americans had even entered the war. There deliberately isn't a shred of truth in David Twohy's Below (2002), which was produced and co-written by Darren Aronofsky, and records the increasingly unnerving events occurring aboard the USS Tiger Shark after it rescues the survivors of the hospital ship, Fort James, from the Atlantic in August 1943.

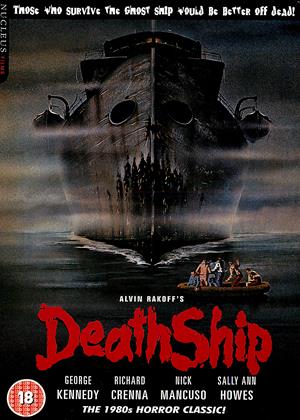

This wasn't the first spooky maritime tale with a wartime connection, however, as Alvin Rakoff's Death Ship (1980) pitches retiring cruise captain George Kennedy and six fellow survivors into the drink after a Caribbean collision with a mysterious freighter. However, the vessel responsible for rescuing them is a Nazi prison ship whose crew believe themselves to be living in 1936. A timeslip also impinges upon Stuart Orme's Ghostboat (2006), a tele-adaptation of a George E. Simpson and Neal R. Burger novel that stars David Jason as the sole survivor of the Baltic submarine HMS Scorpion, which mysteriously resurfaces in the path of a Soviet freighter at the height of the Cold War in 1981.

Written 17 years before the outbreak of the Second World War, the F. Scott Fitzgerald story on which David Fincher based The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008) takes the action into 1941, where Benjamin (Brad Pitt) and buddy Mike Clark (Jared Harris) find themselves in Murmansk when the Japanese attack Pearl Harbor. On joining the US Navy, they are given salvage duties and encounter a U-boat while on a tugboat patrol. The skipper of U-156 proves less ruthless, as Uwe Janson reveals in the miniseries, The Sinking of the Laconia (2010). This factual reconstruction stars Ken Duken as Korvettenkapitän Werner Hartenstein, who targets the British troopship RMS Laconia in September 1942 on its voyage from South Africa. But, having realised that there are women, children, civilians and Italian POWs in the water, he takes the unprecedented step of trying to recover them.

A decade may have passed since this two-parter was broadcast, but the fascination with the war at sea continues to exert its pull, hence CS Forester's novel, The Good Shepherd, being reworked by Aaron Schneider as Greyhound for Tom Hanks to promote once the ongoing pandemic permits.

Escaping is Verboten

No sub-genre of the war film has adhered to the rules of engagement more strictly than those set in prisoner of war camps. The game was simple. POWs had a duty to escape and the guards were under orders to stop them. Although the setting might change, the Allied character types essentially remained the same, whether the sadistic commandants were German or Japanese. As we shall be covering the Pacific War in a later article, the Cinema Paradiso focus here falls squarely on Occupied Europe, where Frank Launder's Two Thousand Women (1944) had the distinction of being the first British feature about detainees.

Set in the Marville internment camp, this stellar drama was given exemption from the wartime blackout on POW pictures that had been imposed to prevent escape secrets from being accidentally betrayed to the enemy. Flora Robson, Phyllis Calvert and Patricia Roc excel in seeking out a traitor within the ranks and hiding three RAF survivors from a crashed bomber. As the cast includes Carmen Silvera, it's tempting to suggest that this subplot had an impact on David Croft and Jeremy Lloyd's impish BBC sitcom, 'Allo, 'Allo! (1982-92).

Despite their scripts being peppered with choice snippets of stiff-upper British humour, POW movies were largely serious affairs, as the penalty for being caught in the act of escaping was death. Almost as soon as the war ended, a number of camp memoirs were published and film-makers snapped up the rights. Among the first to reach the screen was Basil Dearden's The Captive Heart (1946), which was based on the relationship between Josef Bryks, a Czechoslovakian officer in the RAF Volunteer Reserve, and WAAF Gertrude Dellar, whose pilot husband had been killed in action. Married stars Michael Redgrave and Rachel Kempson played the corresponding couple, but the grittier drama centred on Redgrave coming under suspicion of being a Nazi plant while trying to hide the fact that he is actually a fugitive from the Dachau concentration camp.

One of the bestselling 'now it can be told' stories to raise the spirits in Austerity Britain was written by Eric Williams, who fictionalised his own exploits in Stalag Luft III as the screenwriter of Jack Lee's The Wooden Horse (1950), which recast Williams and fellow escapees Michael Codner and Oliver Philpot as Flight Lieutenant Peter Howard (Leo Genn), Captain John Clinton (Anthony Steel) and Flying Officer Philip Rowe (David Tomlinson). Less well known, but equally ingenious was the dummy made by John Worsley to maintain appel numbers at the Marlag O camp for naval officers in northern Germany. This mannequin is the eponymous hero of Lewis Gilbert's Albert RN (1953), which stars Anthony Steel in the Worsley role of Lieutenant Geoffrey Ainsworth and the ever-hissable Anton Diffring as SS Hauptsturmführer Schultz.

Anthony Valentine was even more detestable as Major Horst Mohn in the BBC series, Colditz (1972), which proved such a hit with younger audiences that it inspired the board game, Escape From Colditz. Edward Hardwicke took the role of escape officer Pat Grant, who was based on Major Pat Reid, whose bestselling account of his own escape from Oflag IV-C formed the basis of Guy Hamilton's The Colditz Story (1955), in which Reid was played by the indomitable John Mills. Anton Diffring plays yet another loathsome Nazi and he also crops up in Lewis Gilbert's Reach For the Sky (1956), the hugely popular drama based on Paul Brickhill's biography of Group Captain Douglas Bader (Kenneth More), who wound up in Colditz after repeated escape attempts from other camps, despite the fact that Bader had lost his legs in a flying accident in December 1931.

Stuart Orme returned to the former castle of the Electors of Saxony for the BBC saga, Colditz (2005), which sees escapee Damien Lewis have mixed feelings about the breakout bid being made by Laurence Fox, Jason Priestley and Tom Hardy because he has fallen for the latter's girlfriend in London. The new decade saw the conventions of the POW picture being gently joshed in Ken Annakin's Very Important Person (1961), which teams James Robertson Justice, Leslie Phillips and Stanley Baxter as fliers who plan to walk out of their camp disguised as Red Cross visitors.

A certain drollery resurfaces in Jean Renoir's The Vanishing Corporal (1962), which features Jean-Pierre Cassel as the elusive escaper in this adaptation of a Jacques Prévert novel that stands in stark contrast (despite sharing several key themes) to Renoir's classic Great War POW drama, La Grande Illusion (1937).

By comparison, the action borders on farce in Jonathan Barré's The Comic Adventures of Max and Léon (2016), which sees bunglers Max (David Marsais) and Leon (Grégoire Ludig) captured in the Levant and returned to detention in Vichy. The mood is markedly more sombre, however, in the standout French film about wartime prisoners, Robert Bresson's A Man Escaped (1956). Inspired by the memoir of André Devigny, this monochrome masterpiece chronicles in compelling close-up detail the efforts of French Resistance member Fontaine (François Leterrier) to find a way out of the impregnable Montluc prison in Lyon.

Equally gruelling, but engrossing is the 'Ostinato Lugubre' episode in Andrzej Munk's Eroica (1958), which shows how Lieutenant Zawistowski (Tadeusz Lomnicki) becomes a hero to his fellow Poles when he announces that he is going to break out of an escape-proof German camp. However, a dark truth lurks behind his disappearance and harsh reality also bites in Alexei Sidorov's Iron Fury (2018), when Red Army Lieutenant Nikolay Ivushkin (Alexander Petrov) is plucked from a POW camp in 1944 and ordered to repair a T-34 tank so that can be used for target practice in training Panzer squads.

Camps Across the Continent

Not all POW films were about Allied captives, however. In 1957, Roy Ward Baker's The One That Got Away recounted the extraordinary exploits of Luftwaffe pilot Franz von Werra, who broke out of camps in Lancashire, Derbyshire and Ontario in becoming the only German POW to complete a home run during the entire war. Making the picture particularly pertinent was the fact that the lead was taken by Hardy Krüger, who had himself escaped from the Americans on three separate occasions. The plotter in Lamont Johnson's The McKenzie Break (1970) is U-boat skipper Helmut Griem, who poses problems for martinet commandant Ian Hendry who resents the fact that Irishman Brian Keith has been sent to the Highlands to assess his tactics.

Love is in the air in Terence Ryan's The Brylcreem Boys (1998), which reflects on the fact that Allied and Axis POWs were forced to share the same camps in neutral Ireland. However, Commandant O'Brien (Gabriel Byrne) runs a relaxed ship and, consequently, Royal Canadian Air Force pilot Miles Keogh (Billy Campbell) and Luftwaffe ace Rudolph von Stegenbek (Angus Macfadyen) both wind up falling for the same winsome colleen, Mattie Guerin (Jean Butler).

The scenery is markedly more windswept in Hardy Martins's As Far As My Feet Will Carry Me (2001), which reworks a Josef Martin Bauer novel that was inspired by the travails of Cornelius Rost, who is reimagined as Wehrmacht soldier Clemens Forell (Bernhard Bettermann), who walks 8000 miles across Europe after escaping from a gulag after being sentenced to 25 years for crimes against the Soviet partisans. A similar tale is told by Peter Weir in The Way Back (2010), which appropriates the memoir of Pole Slawomir Rawicz to allow Jim Sturgess, Ed Harris and Colin Farrell and their fellow gulag inmates to travel 4000 miles from Siberia through Mongolia and the Himalayas to India. The immediate postwar period also provides the setting for Tom Roberts's In Tranzit (2008), which follows Thomas Kretschmann and his German subordinates to the all-female transit camp run outside Leningrad by the brutal John Malkovich and his empathetic medical officer, Vera Farmiga.

Billy Wilder took a more sardonic approach to the plight of Allied POWs in Stalag 17 (1953), a transfer of Donald Bevan and Edmund Trzcinski's acclaimed play about a camp on the River Danube that earned William Holden the Oscar for Best Actor for his performance as JJ Sefton, who is suspected of being in cahoots with the guards after commandant Colonel von Scherbach (Otto Preminger) discovers a top-secret tunnel. Having escaped from separate camps, Brits Stephen Boyd and Tony Wright make their way to Marseille in 1943 in the hope of securing a passage home in Hugo Fregonese's Seven Thunders (1957).

There can't be many film fans who aren't aware of the events that took place in Stalag Luft III outside the Lower Silesian town of Sagan. Adapted from a book by Paul Brickhill, John Sturges's The Great Escape (1963) boasts an all-star cast that includes Charles Bronson, James Garner and Richard Attenborough. But the scene most people remember involves Steve McQueen as Captain Virgil Hilts (aka The Cooler King) and his attempt to jump a barbed wire fence on a stolen motorcycle.

The Italian theatre provides the backdrop for Mark Robson's Von Ryan's Express (1965), an adaptation of a David Westheimer novel that stars Frank Sinatra as USAF pilot Colonel Joseph Ryan, whose reluctance to commit to the escape plans hatched by British major Erich Fincham (Trevor Howard) is ditched when he hits upon a scheme to steal a train and make a dash for the Swiss border. The Alps also look likely to provide an insurmountable problem for Oliver Reed in the title role of Michael Winner's Hannibal Brooks (1969), as his mission to escort an elephant named Lucy from a zoo in Munich to the Austrian city of Innsbruck is similarly detoured towards the neutral zone.

No POW movie comes closer to pure escapism (in every sense of the word) than John Huston's Escape to Victory (1981), which features a squad of famous footballers, including Pelé and Bobby Moore, teaming up with Michael Caine and Sylvester Stallone in an audacious bid to escape at half-time during an exhibition match in Paris against a crack Nazi XI.

The three-time Brazilian World Cup winner is one of the few black POWs seen in any of the aforementioned films. But his acceptance stands in stark contrast to the frosty reception accorded Tuskegee Airman Terrence Howard when he arrives at Stalag VI-A in Gregory Hoblit's Hart's War (2002). However, when he's accused of murdering a racist bigot, Colonel Bruce Willis forces First Lieutenant Colin Farrell to defend him in a court-martial that has been designed to preoccupy the German guards.

A Greek island becomes home to POW David Niven and the members of a detained USO concert party in George Pan Cosmatos's Escape to Athena (1979), which sees partisans Telly Savalas and Claudia Cardinale plot to disrupt the dig for antiquities being overseen by Austrian commandant, Roger Moore. But only Billy Pilgrim (Michael Sacks) manages to be detained by both the Nazis and a race of aliens, as George Roy Hill reveals in his potent adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut's novel, Slaughterhouse-Five (1972), which chillingly contrasts the American's experiences as a research specimen on the Planet Tralfamadore and as a witness to the Allied fire-bombing of the German city of Dresden.

Are there any films you would add to this overview? And what do you think makes a good military drama? Don't forget you can watch all of these films with our Free Trial offer!