As a number of Agnès Varda classics are revived and her final outing is released, the wonderful Faces Places, Cinema Paradiso pays tribute to the female film-makers who have long played a part in shaping the course of French cinema.

Alice and the Avant-Gardists

By rights, the name of Alice Guy-Blaché should be immortalised among the pioneers of the moving image. Having attended the first public screening of the Lumière Cinématographe on 22 March 1895, she persuaded boss Léon Gaumont to allow her to make a film and The Cabbage Fairy (1896) became the first motion picture to be directed by a woman. What's more, Guy used a shooting script and was soon displaying such a talent for storytelling and stylistic innovation that she became the nascent studio's head of production.

In 1907, Guy married cameraman Herbert Blaché and they relocated to Fort Lee in New Jersey to set up the Solax company. Among her releases was A Fool and His Money (1912), which is presumed to be the first film with an all-African-American cast. However, her career came to an abrupt end following her divorce from Blaché and return to France in 1922. She spent her remaining years ensuring that her legacy was respected, she only received the Legion of Honour in 1953 and her achievement has only recently been fully recognised.

As French cinema developed, actresses like Musidora, Renée Carl. Marie-Louise Iribe, Rose Pansini, Fabienne Fabrèges and Diana Karenne tried their hand at directing. But a handful of artists rebelled against commercial convention and sought to create a filmic equivalent of Impressionism. Among them were Lucie Derain (Désordre, 1927) and Marie Epstein, who co-directed a number of films with Jean Benoît-Levy, including Peach Skin (1929). The leading light, however, was Germaine Dulac, who abandoned traditional narrative after collaborating with Louis Delluc on La Fête espagnole (1919). Striving to fashion an 'integral cinema' that discarded representational meaning to allow an abstract exploration of feelings and dreams, Dulac caused such a stir with The Smiling Madame Beudet (1923) and The Seashell and the Clergyman (1927) that the British censor declared her work to be 'so cryptic as to be almost meaningless. If there is a meaning it is doubtless objectionable.'

Sound Silences the Female Voice

The nature of film-making changed with the coming of talking pictures and Marie Epstein, Solange Bussi and Marguerite Viel were the only women to direct features in France over the next two decades. After the war, Marie-Anne Colson-Malleville, Denise Dual and Hélène Dassonville experimented with documentary and montage films, the most admired of which was Nicole Védrès's Paris 1900 (1947), which provided a welcome shot of fin-de-siècle nostalgia. Andrée Feix (Once Is Enough, 1946) and Caro Canaille (Si le roi savait ça, 1958) also made fictional features. But the most notable female director of this period was Jacqueline Audry.

Having served as an assistant to GW Pabst, Max Ophüls and Jean Delannoy, Audry made her feature bow with The Misfortunes of Sophia (1945). She forged a postwar partnership with the writer Colette and enjoyed a degree of success with Gigi (1948), Minne (1950) and Mitsou (1956). But her best-known works were her adaptations of Dorothy Bussy's finishing school saga, Olivia (1951), and Jean-Paul Sartre's infernal triangle, Huis clos (1954). While Audry interpreted the writing of others, Marguerite Duras produced her own scripts after famously collaborating with Alain Resnais on Hiroshima mon amour (1959). De-emphasising the narrative to focus on human experience and relationships, the impact of time upon memory and the distinction between subjectivity and objectivity, Duras's most accomplished pictures include Nathalie Granger (1972). India Song (1975), Le Camion and Baxter, Vera Baxter (both 1977). Yet, despite their importance, only a few of Audry and Duras's films are available on disc, even in France.

Access is also limited to the intellectually rigorous and stylistically radical collaborations between Danièle Huillet and her husband, Jean-Marie Straub, whose most accessible work is the monochrome biopic, The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (1968). Belgian Chantal Akerman also made demands on the audience in studied feminist non-dramas like Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) and Je, tu, il, elle (1974). But the contribution that Agnès Varda made to the nouvelle vague opened doors for a new generation women film-makers like Yannick Bellon (Rape of Love, 1968), Nelly Kaplan (Dirty Mary, 1969), Nina Companeez (Faustine and the Beautiful Summer, 1972) and Diane Kurys (Peppermint Soda, 1977).

Critical Acclaim vs Commercial Success

One of the first French women directors to score an international hit in this period was Coline Serreau, whose Three Men and a Cradle (1986) was remade in Hollywood by Leonard Nimoy as Three Men and a Baby (1987). Indeed, Tom Selleck, Steve Guttenberg and Ted Danson reunited for Emile Ardolino's Three Men and a Little Lady, which was released the year after Serreau scored again at the box office with Mama, There's a Man in Your Bed (1989), which followed the romance between businessman Daniel Auteuil and his black cleaner, Firmine Richard.

Auteuil also teamed with Josiane Balasko in My Life Is Hell (1991), in which he plays a satanic envoy who mistakenly buys the soul of a dowdy nurse. A stellar comic actress in her own right, Balasko has a gift for sparky comedies, as she proved in winning a César for her screenplay for French Twist (1995), in which she also stars as a lesbian luring Victoria Abril away from cheating husband Alain Chabat, and in teaching surly pharmacist Michel Blanc a lesson in Half-Sister (2013). Another accomplished actress who has developed into a fine director is Nicole Garcia, who guided Catherine Deneuve through the shady underworld of the illegal diamond trade in Place Vendôme (1998), pitched supply teacher Pierre Rochefort in a tricky situation in Going Away (2013) and lured Marion Cotillard into an adulterous affair with Louis Garrel in From the Land to the Moon (2016).

Finding funding has always proved problematic for emerging women film-makers and the likes of Claire Devers (Noir et blanc, 1986), Christine Pascal (Le Petit Prince a dit, 1992), Aline Issermann (L'Ombre du doute, 1993) and Claire Simon (A Foreign Body, 1997) struggled to build on critical acclaim. Even those who have enjoyed success overseas have not always been able to repeat the feat, with Martine Dugowson (Portraits Chinois, 1996), Marion Vernoux (Love, Etc., 1996), Agnès Merlet (Artemisia, 1997). Tonie Marshall (Venus Beauty, 1998), Sandrine Veysset (Will It Snow For Christmas?, 1998), Laetitia Masson (For Sale, 1998) and Noémie Lvovsky (Camille Rewinds, 2012) among those who deserve to be much better known outside France.

A New Breed

Around the turn of the century, French women film-makers began tackling topics that had previously been considered taboo. Among the most controversial outings was Virginie Despentes and Coralie Trinh Thi's Baise-Moi (2000), which accompanied rape victim Raffaela Anderson and prostitute Karen Bach on a pitiless revenge mission. Marina de Van used equally unflinching tactics in considering the issue of self-harming in In My Skin (2002), in which she also starred as a Parisian marketing executive who indulges in increasingly extreme acts of mutilation. But Julia Ducournau went further still in Raw (2016), one of the most gruelling horror films of recent times, in which vegetarian veterinary student Garance Marillier develops a ravenous taste for flesh.

Parisian Hélène Cattet and husband Bruno Forzani have also specialised in keeping audiences on the edge of their seats. The influence of the Italian giallo tradition is readily evident in Amer (2009), which charts three episodes in a young woman's psycho-sexual maturation, and The Strange Colour of Your Body's Tears (2013), which follows Klaus Tange's efforts to find the wife who has mysteriously disappeared from their locked apartment. Cattet and Forzani also contributed the 'O Is for Orgasm' episode to the 2012 horror portmanteau, The ABCs of Death.

De Van ventured into more traditional chiller territory in Dark Touch (2013). But Alice Winocour provides a disconcerting insight into fin-de-siècle attitudes to mental health in Augustine (2012), which focuses on the efforts of doctor Jean-Martin Charcot (Vincent Lindon) to determine what ails a kitchen maid (Soko) prone to violent fits. In addition to co-scripting Deniz Gamze Ergüven's simmering tale of daughterly rebellion, Mustang, Winocour has also directed Disorder (both 2015), in which Matthias Schoenaerts plays a soldier suffering from post-traumatic stress after a tour in Afghanistan, who is detailed to protect tycoon's wife Diane Kruger in her Riviera villa.

Rebecca Zlotowski has also divided her time between directing and writing for others. Having explored the darker side of desire in Yann Gonzalez's You and the Night (2013) and Philippe Grandrieux's Despite the Night (2016), she turned her attention to the safety of nuclear power in pairing Tahar Rahim and Léa Seydoux in Grand Central (2013) and the potential of psychic power in casting Natalie Portman and Lily-Rose Depp as American mediums in 1930s Paris in The Summoning (2016). Another director with a notable writing credit to her name is Pascale Ferran, who joined forces with Michael Dudok de Witt on the beguiling animation, The Red Turtle (2016). Behind the camera, Ferran made a stylish job of adapting DH Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover (2006), with Marina Hands and Jean-Louis Coulloc'h, while she drew delightful performances out of Anais Demoustier and Josh Charles, as a hotel maid and a Silicon Valley engineer, in the modern-day fairytale, Bird People (2014).

No other country in Europe affords its female film-makers more opportunities to realise their potential and Cinema Paradiso invites users to sample features by such emerging talents as Sophie Barthes (Cold Souls, 2009 & Madame Bovary, 2014), Mona Achache (The Hedgehog, 2010), Emmanuelle Bercot (Student Services, 2010 & The Players, 2014), Maïwenn (Polisse, 2011 & My King, 2015), Sylvie Verheyde (Confession of a Child of the Century, 2012 & The Working Girl, 2016), Valérie Lemercier (The Ultimate Accessory, 2013) and Eva Husson (Bang Gang: A Modern Love Story, 2015). But it also has a generous selection of the key works by the 10 most significant femmes auteurs.

Agnès Varda

It's hard to think of anyone who could rival 90-year-old Agnès Varda for the title of the most important female film-maker in screen history. Born in Brussels, but raised in Sète in Provence, Varda struggled to settle in Paris during her student days and only found her niche in the early 1950s as the official photographer at the Théâtre National Populaire. Despite not having seen many films, she returned to Sète to make her first feature, La Pointe Courte (1954), a realist study of local Philippe Noiret's strained marriage to Parisienne Silvia Monfort that anticipated many of the stylistic traits that would characterise the nouvelle vague. Married to fellow auteur Jacques Demy, Varda was associated with the Left Bank group of film-makers, although Jean-Luc Godard cameo'd in the film-within-the-film in Cléo From 5 to 7 (1961), which confirmed her signature style of 'cinécriture' (or 'cine-writing') in following singer Corinne Marchand around Paris as she awaits the results of some medical tests. Everyday preoccupations are also to the fore in Le Bonheur (1965), a breezily pessimistic investigation of domestic contentment that charts the impact on the marriage of carpenter Jean-Claude Drouot and his dressmaker wife Claire Drouot of his affair with postal worker, Marie-France Boyer.

Following a prolonged spell in California, Varda returned to France to assess how feminism was affecting ordinary Frenchwomen in One Sings, the Other Doesn't (1977), which sprawls over a decade to recount the fragmented friendship between a country girl and single mother Thérèse Liotard and younger Parisienne, Valérie Mairesse. But Varda's hardest hitting treatise on the status of women in a male-dominated society was Vagabond (1985), which won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and earned the César for Best Actress for Sandrine Bonnaire, as a drifter whose cut-short life is pieced together in 47 episodes seen from the perspective of those who barely knew her. Varda was intimately acquainted with the subject of Jacquot de Nantes (1991), which juxtaposed Jacques Demy's childhood obsession with cinema with his untimely AIDS-related death at the age of 59. The concept of mortality has long one of Varda's key themes and it has underpinned the magnificent documentary triptych comprised of The Gleaners and I (2000), The Beaches of Agnes (2008) and Faces Places (2017), which saw Varda become the oldest person to be nominated for a competitive Oscar.

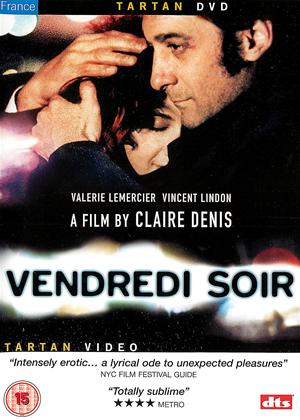

Claire Denis

Born in Paris, but raised in West Africa, Claire Denis has revisited the colonial experience in three of her most memorable films. In her feature bow, Chocolat (1988), she explored the friendship between governor's daughter Cécile Ducasse and Cameroonian house servant Isaach de Bankolé, who returned to play a rebel leader laying low in Isabelle Huppert's coffee plantation in White Material (2009). In between these contrasting studies, Denis reworked Herman Melville's novel Billy Budd (and the Benjamin Britten opera it inspired) as Good Work (1999), which centres on the fractious relationship between officer Denis Lavant and new recruit Grégoire Colin at a Foreign Legion base in Djibouti.

Unsure that she wanted to make pictures after leaving the Parisian film school, La Fémis, Denis worked as an assistant to Jacques Rivette, Wim Wenders and Jim Jarmusch. The influence of the latter pair has been detected in Nénette and Boni (1996) and The Intruder (2004), with the former initiating a long-standing partnership with screenwriter Jean-Pol Fargeau, composer Stuart Staples and cinematographer Agnès Godard that continued through such contrasting outings as the body horror Trouble Every Day (2001), the chance romance, Vendredi Soir (2002), and the macabre sex-trafficking noir, Bastards (2013). But, despite the collaborative nature of her approach, Denis has devised a pared-down poetic style that could be called a cinema of moments, as she alights on key encounters and exchanges, such as those between train driver Alex Descas and anthropology student daughter Mati Diop in 35 Shots of Rum (2008) and artist Juliette Binoche's liaisons with banker Xavier Beauvois, actor Nicolas Duvauchelle, gallerist Bruno Podalydès and fortune teller Gerard Depardieu in Let the Sunshine In (2017).

Catherine Breillat

Controversy has shrouded Catherine Breillat's career since her first feature, A Real Young Girl (1976), was withheld from release for 21 years. Adapted from a novel that Breillat had written when she was 17, this was the first of her trademark studies of women gaining an understanding of their sexuality. Often provoking with their unflinching attitude to physical passion, 36 Fillette (1988), Perfect Love (1996), Romance (1999) and Brief Crossing (2001) all covered similar territory, as had Bernardo Bertolucci's Last Tango in Paris (1972), in which Breillat had acted alongside sister Marie-Hélène, and David Hamilton's Bilitis (1977), which Breillat had co-written. With its scenes of unsimulating coupling, Romance caused additional furore through the casting of Italian porn star Rocco Siffredi. But, undaunted, Breillat hired him again for Anatomy of Hell (2004), in which he is challenged by wrist-slash victim Amira Casar to witness four nights of unspeakable acts.

Despite often basing scripts on her own bestselling novels, Breillat has also produced revisionist adaptations of a couple of fairy stories, Bluebeard (2009) and The Sleeping Beauty (2010), as well as a plush take on Jules-Amédée Barbey d'Aurevilly's 1851 tome, The Last Mistress (2007), which marked her return to film-making after suffering a paralysing cerebral hemorrhage in 2004. During her convalescence, Breillat embarked upon a collaboration with conman Christophe Rocancourt and she chronicled how he duped her in Abuse of Weakness (2013), which has yet to be released on disc, despite co-starring Isabelle Huppert and Kool Shen. She also put an autobiographical spin on Sex Is Comedy (2002), which was inspired by the awkwardness she felt directing the bedroom scene in Fat Girl (2001).

Anne Fontaine

Raised in Lisbon after being born in Luxembourg, Anne Fontaine came to Paris as a teenager to study dance. Having drifted into acting in films like David Hamilton's Tender Cousins (1980), she broke into directing with a trio of films about an unassuming everyman named Augustin, which starred her brother, Jean-Chrétien Sibertin-Blanc. Her first critical acclaim came for Dry Cleaning (1997), which earned her a César nomination for Best Screenplay, and she reunited with star Charles Berling for How I Killed My Father (2001), in which he played a doctor resenting the reappearance of estranged parent, Michel Bouquet (who won the César for Best Actor). Fanny Ardant similarly discovers more than she wants to know when she hires escort Emmanuelle Béart to test the fidelity of husband Gérard Depardieu in Nathalie (2003) and adultery rears its head again when Gemma Arterton and Jason Flemyng move to the Normandy countryside in Gemma Bovery (2014). Fontaine went into costume mode for Coco Before Chanel (2009) and The Innocents (2016), which featured outstanding performances by Audrey Tautou and Lou de Laâge, while Finnegan Oldfield earned a César nomination as Best Newcomer in Reinventing Marvin (2017), a gay rite of passage (due soon in selected UK cinemas) that also features Charles Berling and Isabelle Huppert, who had previously worked with Fontaine on My Worst Nightmare (2011), which had co-starred Benoît Poelvoorde, who had headlined Entre ses mains (2005), which drew Fontaine's second writing nomination at the Césars.

Catherine Corsini

Obsessed with cinema from an early age, Catherine Corsini trained to be an actress before she started directing shorts in the early 1980s. Having made her feature bow with Poker (1987), she produced the coming out story, Lovers (1994), between television assignments. British audiences first became acquainted when Karin Viard was hailed as the French Bridget Jones after dithering between married socialist Pierre-Loup Rajout and romantic trucker Sergi López in The New Eve (1999). But a decade passed before Corsini graced our screens again, by which time she had chronicled Pascale Bussières's dangerous obsession with old friend Emmanuelle Béart in Replay (2001), paired Jane Birkin and Émile Dequenne as a gold-digging granny and her granddaughter in The Very Merry Widows (2003) and revealed how snooty editor Karin Viard and timid author Éric Caravaca found love in Les Ambitieux (2006). Illicit romance was also to the fore in Leaving (2009), as physiotherapist Kristin Scott Thomas is tempted to betray husband Yvan Attal with ex-jailbird builder Sergi López. Yet, despite good reviews, the hit-and-run drama, Three Worlds (2012) failed to find a UK distributor. However, Summertime (2015) was warmly welcomed for its sun-dappled views of Limousin in the early 1970s and its involving story about farmer's wife Noémie Lvovsky's response to daughter Izia Higelin falling for lesbian feminist, Cécile de France.

Agnès Jaoui

A familiar face from her performances in films as different as Bruno Podalydès's The Sweet Escape (2015) and Blandine Lenoir's I Got Life! (2017), Agnès Jaoui is also a garlanded writer-director. She has regularly collaborated with actor Jean-Pierre Bacri since they appeared together in a Harold Pinter production in 1987, winning a César for their script for Alain Resnais's two-part Alan Ayckbourn adaptation, Smoking/No Smoking (1993). They repeated the feat with their sparkling screenplays for Cédric Klapisch's Une Air de famille (1997) and Resnais's Same Old Song (1997), which also saw Jaoui take the prize for Best Supporting Actress. She made her directorial bow with The Taste of Others (2000), a culture clash romcom involving Bacri's uncouth businessman and married actress Anne Alvaro that not only won Césars for Best Screenplay and Best Film, but which was also nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film. Bacri and Jaoui landed the script prize at Cannes for Look At Me (2004), in which they also co-starred as the publisher father and music teacher of Marilou Berry, whose acting ambitions are being hampered by her poor body image. The duo remained in a satirical mood in Let's Talk About the Rain (2007), in which Bacri and Jamel Debbouze play inept documentarists making a film about Jaoui's complacent politician during a visit to her southern home town. Yet, despite splitting as off-screen partners in 2012, Jaoui and Bacri continue to make an irresistible team, as they proved with Under the Rainbow (2013), which borrowed from the fables of Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm for its account of twentysomething Agathe Bonitzer's search for Prince Charming.

Lucile Hadžihalilovic

Born to Bosnian parents and raised in Morocco, Lucile Hadžihalilovic graduated from La Fémis with La Premiere Mort de Nono (1987), a gay first love story that she followed almost a decade later with La Bouche de Jean-Pierre (1996), in which a young girl follows her mother in attempting suicide. In between these acclaimed shorts, Hadžihalilovic formed Les Cinémas de la Zone with Gaspar Noé and served as editor on his 1991 short, Carne, as well as the 1998 feature, I Stand Alone. She also received a writing credit on Enter the Void (2009), by which time Hadžihalilovic had made her directorial debut with Innocence (2004), an adaptation of Frank Wedekind's 1903 novel, Mine-Haha, or On the Bodily Education of Young Girls, which starred Marion Cotillard and Hélène de Fougerolles as teachers at the sinister school run by headmistress, Corinne Marchand. Taking its inspiration from Victor Erice's The Spirit of the Beehive (1973), Peter Weir's Picnic At Hanging Rock (1975) and Dario Argento's Suspiria (1977), as well as Enid Blyton's Mallory Towers books, this unsettling saga was followed by the equally disconcerting Evolution (2015), an audaciously stylised body horror set in a community populated solely by single mothers and their sons, which sees 10-year-old Max Brebant become suspicious of the treatments being administered in the local hospital by nurse Roxane Duran.

Céline Sciamma

In addition to becoming firm friends with Rebecca Zlotowski and Marie Amachoukeli (Party Girl, 2014) while studying at La Fémis, Céline Sciamma also came under the influence of her renowned film-making tutor Xavier Beauvois (Of Gods and Men, 2010). She also forged a partnership with Jean-Baptiste de Laubier, as she co-wrote the screenplays for his shorts. Les Premières communions (2004) and Cache ta joie (2006), and he went on to compose the score (under the name Para One) for Sciamma's 'coming of age' trilogy. The 27-year-old debutant made an excellent impression with Water Lilies (2007), which earned César nominations for herself and Adèle Haenel and Louise Blachère, as two parts of a romantic triangle that was completed by Pauline Acquart, their 15-year-old teammate in a synchronised swimming squad. Self-discovery is also the theme of Tomboy (2011), as 10 year-old Zoé Héran takes advantage of moving to a new neighbourhood to pass herself off as a boy for the summer, and Girlhood (2014), as Karidja Touré and friends Assa Sylla, Lindsay Karamoh and Mariétou Touré break out of their mundane banlieue existence to sample the forbidden delights of Paris. Sciamma is currently making Portrait de la jeune fille en feu with her partner, Adèle Haenel. So, while you're waiting, why not try to catch Claude Barras's My Life As a Courgette (2016), which boasts Sciamma among its writers?

Katell Quillévéré

Born in the Ivorian capital Abidjan, Katell Quillévéré bounced back from being rejected by La Fémis by being nominated for a César with her 2005 short, À Bras le corps. She received the Prix Jean Vigo with her feature debut, Love Like Poison (2010), which took its title from a Serge Gainsbourg song. Set in the Brittany of Quillévéré's youth, this rite of passage centres on teenager Clara Augarde's crisis of faith, as she returns from boarding school for her confirmation to discover that her parents have decided to separate. Keeping the focus on family ties in Suzanne (2013), Quillévéré drew on Maurice Pialat's brand of social realism to relate a story that sprawls across 25 years to chronicle the relationship between sisters Sara Forestier and Adèle Haenel and their supportive father, François Damiens. Among the film's five César nominations was a Best Supporting Actress win for Haenel, while Quillévéré received her second César citation for Heal the Living (2016), a tense and deeply moving ensemble adaptation of a Maylis de Kerangal novel about the heart transplant connection between teenage surfer Gabin Verdet and middle-aged musician, Anne Dorval.

Mia Hansen-Løve

The daughter of Parisian philosophy teachers, Mia Hansen-Løve had her first taste of film-making as an actress in Late August, Early September (1998) and Les Destinées sentimentales (2000), which were directed by her future partner, Olivier Assayas. Having made six shorts in two years while writing for Cahiers du Cinéma, Hansen-Løve made an immediate impression behind the camera with All Is Forgiven (2007), which earned her a César nomination for Best First Feature. However, she won the Special Jury Prize at Cannes for Father of My Children (2009), which was inspired by the suicide of producer Humbert Balsan and starred Louis-Do and Alice de Lencquesaing as a seemingly successful film producer and the daughter who discovers his double life after his death. Another young woman learns about life the hard way in Goodbye First Love (2011), as 15-year-old Lola Créton is crushed when she's dumped by 19-year-old boyfriend Sebastian Urzendowsky. But, by the time their paths cross again, she has found happiness with architecture tutor Magne Håvard-Brekke. Changing tack, Hansen-Løve took inspiration from her brother Sven's career as a club DJ in the 1990s in Eden (2014), which starred Félix de Givry as a student whose hedonistic lifestyle catches up with him when he makes it big on the rave scene. Despite once again basing the action on a family member, this time her mother, Hansen-Løve resumed her more familiar Rohmeresque style with Things to Come (2015), which brought her the Silver Bear for Best Director at the Berlin Film Festival and features a powerhouse performance from Isabelle Huppert rediscovering a sense of self and freedom after separating from her husband of 25 years.

Even more films...

If you're interested in French cinema, be sure to check out our World Cinema section where you can filter titles by country including French films.