Can there be a more recognisable face in the whole of screen history than Marilyn Monroe's? Her legend has grown in the 59 years since she died alone in what many consider to have been suspicious circumstances on 4 August 1962. In the latest entry in the popular Getting to Know series, Cinema Paradiso looks back on the troubled life of a star who burned brightly, but all too briefly.

Six decades after her tragically early death, Marilyn Monroe remains a cultural icon. Yet opinion is divided over her legacy. Some see her as the victim of the male-dominated studio system, while others regard her as an emancipator who subverted social and sexual convention. Monroe herself once averred, 'my popularity seems almost entirely a masculine phenomenon'. But sex appeal was only one of the reasons why Marilyn caught the public imagination and transformed the nature of 20th-century celebrity.

Marilyn Monroe: Norma Jean Mortensen

Norma Jeane Mortenson was born at the Los Angeles County Hospital on 1 June 1926. Her mother, Gladys Mortensen, named her after silent film star Norma Talmadge, who is mentioned in Peter Bogdanovich's documentary, The Great Buster: A Celebration (2018), because her sister, Natalie, had wed slapstick genius, Buster Keaton.

Gladys had married Jasper Baker when she was 15 and had suffered the heartache of having children Robert and Berniece kidnapped by their father, following a messy divorce. Robert died when Norma Jeane was young and she only discovered she had a sister when she was 12, although they didn't meet until they were adults.

While working as a negative cutter at Consolidated Film Industries, Gladys married Martin Mortensen. However, they separated after only a few months and many have speculated that Norma Jeane's father was Gladys's shift foreman, Charles Gifford. Having been registered with the misspelt surname, 'Mortenson' on her birth certificate, the baby was bapstised Norma Jeane Baker at the insistence of her grandmother, Della, to cover the fact she was illegitimate.

Sadly, Della died soon afterwards. So, when Gladys decided she couldn't care for her child, Norma Jeane was placed with foster parents Albert and Ida Bolender in the country town of Hawthorne. Gladys lived nearby until she had to return to the city for work. But, in the summer of 1933, she bought a small house in Hollywood, where Norma Jeane lived for a few months with actor lodgers George and Maude Atkinson and their daughter, Nellie.

In January 1934, however, Gladys was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and was committed to the Metropolitan State Hospital. Norma Jeane rarely saw her mother again, as she became a ward of the state under the care of Gladys's friend, Grace Goddard, and her husband, Erwin, who was nicknamed 'Doc'. They housed Norma Jeane after she had suffered sexual abuse while living with the Atkinsons. But the arrangement only lasted a few months and, in September 1935, Norma Jeane was sent to the Los Angeles Orphans Home.

A shy girl who had developed a stutter, Norma Jeane felt she had been abandoned and the orphanage tried to persuade the Goddards to take her back. However, her return in the summer of 1937 proved short-lived, as Doc preyed upon her and Norma Jeane was passed between various relatives and members of Grace's social circle. In order to get her out of the house, these carers often sent her to the local movie theatre, where she would 'sit all day and way into the night. Up in front, there with the screen so big, a little kid all alone, and I loved it.'

In September 1938, the 12 year-old Norma Jeane found a home with Grace Goddard's aunt, Ada Lower, in Sawtelle. She started to attend Emerson Junior High School and contributed to the student newspaper. However, this relatively stable period was soon over and Norma Jeane was forced to return to the Goddards in early 1941. When Doc's company transferred him to West Virginia, Norma Jeane seemed set to return to the orphanage, as California child protection laws meant that she couldn't leave the state.

Desperate to avoid more upheaval, Norma Jeane dropped out of Van Nuys High School to marry neighbour James Dougherty, a factory worker who was five years her senior, on 19 June 1942. She hated being a housewife, however, and, when Dougherty enlisted in the Merchant Marine, Norma Jeane readily accompanied him to Santa Catalina Island. When her husband was posted to the Pacific in April 1944, Norma Jeane moved in with in-laws Edward and Ethel and found a job at the Radioplane munitions factory in Van Nuys.

Whatever Happened to Jean Adair?

During a visit to Radiophone to make a newsreel item about female factory workers for the US Army Air Forces' First Motion Picture Unit, photographer David Conover noticed Norma Jeane. He asked her to pose for him and she quit her job against the wishes of her husband. When the Blue Book Model Agency offered to sign her in August 1945, Norma Jeane leapt at the chance and began appearing in advertisements and pin-up shots for men's magazines.

She straightened her hair and dyed it blonde, while also adopting the name Jean Norman for some of her assignments. Moreover, having started to make the cover of a range of glossies, she joined an acting agency in June 1946 and was invited for a screen test at Paramount.

Unfortunately, the studio was unimpressed and production chief Darryl F. Zanuck felt much the same way at 20th Century-Fox. However, executive Ben Lyon was convinced Norma Jeane had something unique and used a potential offer from RKO to goad Fox into giving his discovery a six-month contract. When he suggested a change of name, his protégé came up with 'Jean Adair'. But, as she reminded Lyon of 1920s Broadway star Marilyn Miller, he insisted on twinning her first name with Gladys Baker's maiden name and Marilyn Monroe was born.

A month later, she divorced Dougherty and embraced her new role as a starlet. In addition to taking acting, singing and dance classes, Monroe was also taught how to work with a camera. When her option was taken up by the studio in February 1947, she made her debut in Arthur Pierson's Dangerous Years (1947), as a waitress named Evie at the roadhouse that the ultra-conservative residents are convinced is going to corrupt the youth of Middleton. She followed this with a single-scene bit as Betty in F. Hugh Herbert's tale of feuding farmboys, Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay! (1948). Ironically, the character she greets outside the town church was played by June Haver, who would shortly star as Marilyn Miller in David Butler's biopic, Look For the Silver Lining (1949).

Between these pictures, Fox enrolled Monroe in the Actors' Laboratory Theatre, where she later revealed she got her 'first taste of what real acting in a real drama could be'. Her tutors felt she was too withdrawn to convey complex emotions, however, and Monroe had to return to modelling when Fox let her contract lapse in August 1947.

While making ends meet with odd jobs around the studios, Monroe continued to attend the Actors' Lab and made her stage bow in a short-lived revival of Florence Ryerson's play, Glamour Preferred, at the Bliss-Hayden Theatre. She also befriended gossip columnist Sidney Skolsky and hired herself out as a companion to single male guests at studio functions.

At one of these, she became acquainted with Fox executive Joseph M. Schenck, who used his influence to coax Columbia boss Harry Cohn into offering Monroe a contract in March 1948. He decided to groom her in the manner of his biggest star, Rita Hayworth, who had just sported blonde hair in soon-to-be ex-husband Orson Welles's fiendishly tricksy thriller, The Lady From Shanghai (1947).

Cohn also entrusted Monroe to German acting coach Natasha Lytess. According to some sources, she was Monroe's sexual partner for the first two years of their seven-year working relationship and the Berliner also saved her from a potential sleeping pill overdose. But Lytess also gave Monroe a new acting confidence and, having (depending on which source you consult) taken uncredited extra work on George Seaton's The Shocking Miss Pilgrim (1947), Louis King's Green Grass of Wyoming and Lloyd Bacon's You Were Meant For Me (both 1948), she landed the lead in Phil Karlson's Ladies of the Chorus (1948), which is available to rent on high-quality disc from Cinema Paradiso.

A tale of showbiz and class snobbery, the story centres on the efforts of fading burlesque star Mae Martin (Adele Jurgens) to protect her dancer daughter Peggy (Monroe) from Cleveland socialite, Randy Carroll (Rand Brooks). Yet, despite Monroe's best efforts, the film disappointed and Columbia released her in September 1948.

She adopted the name 'Mona Monroe' to shoot some nude studies for a John Baumgarth calendar. But claims that she appeared in an eight-minute stag film were dispelled when it was revealed that the star of The Apple Knockers and the Coke was actually Arline Hunter.

Fourteen Films in Two Years

Having been cut adrift by Columbia, Monroe took up with Johnny Hyde, who was the vice president of the William Morris Agency. He fixed it for her to be cast in such pictures as David Miller's Marx Brothers romp, Love Happy (1949); Richard Sale's musical Western, Ticket to Tomahawk; and Tay Garnett's roller-skating saga, The Fireball (both 1950).

More promisingly, she found herself in a couple of enduring classics when she played crook's moll Angela Phinlay in John Huston's The Asphalt Jungle and Miss Claudia Cassell, the protégé of theatre critic Addison DeWitt (George Sanders), in Joseph L. Mankiewicz's All About Eve (both 1950), which won six Oscars, including Best Picture. Monroe's performance was commended by Photoplay and Hyde was able to talk 20th Century-Fox into handing her a seven-year contract in December 1950.

Sadly, her guardian angel died the week before Christmas and Monroe spent the next two years in bit parts that traded solely on her looks. She was uncredited as model Dusky Ledoux for her single scene in John Sturges's sports drama, Right Cross (1950), while she merely passes through as secretary Iris Martin in Arthur Pierson's Home Town Story (1951), which follows the efforts of ousted politician Blake Washburn (Jeffrey Lynn) to get himself re-elected by taking over a small-town newspaper.

Playing a printer who disguises himself as a corporate bigwig after being coerced into retirement, Monty Woolley took top billing in Harmon Jones's As Young As You Feel, which saw Monroe play Harriet, the secretary who distracts Louis McKinley (Albert Dekker) from both his business and his wife, Lucille (Constance Bennett). And she had little more to do as ex-WAC Roberta Stevens in Joseph Newman's Love Nest (both 1951), after coming between author Jim Scott (William Lundigan) and his wife, Connie (June Haver), by renting his old New York apartment.

Monroe got positive notices for all three of the titles available from Cinema Paradiso and her star rose further after Richard Sale's Let's Make It Legal (1951), in which she essays gold-digger Joyce Mannering, who tilts her cap at self-made millionaire, Victor Macfarland (Zachary Scott). Her profile was further raised (in some quarters) when American troops fighting in the Korean War voted her 'Miss Cheesecake of 1951' in a poll run by Stars and Stripes magazine.

The accolade may seem distasteful seven decades later. But the Fox front office couldn't ignore such recognition, especially when the Hollywood Foreign Press Association followed it up at the Golden Globes by giving Monroe the Henrietta Award for Best Young Box Office Personality. Moreover, the gossip columnists started picking up on her being seen around town with such directors as Elia Kazan and Nicholas Ray and stars like Yul Brynner and Peter Lawford. She hit the headlines, however, when she started dating New York Yankees baseball legend, Joe DiMaggio, in early 1952.

The year had started well, as she had been cast in Fritz Lang's adaptation of Clifford Odets's play, Clash By Night. During the shoot, however, news broke that Monroe had posed nude for a calendar three years earlier. But, rather than buckle under the scandal, she took ownership of the situation by avowing that she was not ashamed of her body and had taken the work because she was flat broke. The tactic worked, as columnist Hedda Hopper championed Monroe's cause and she even featured on the cover of Life magazine.

Keen to keep Monroe in the spotlight, Fox cast her alongside David Wayne in a vignette about a husband disapproving of his wife's participation in beauty pageants in Edmund Goulding's comic anthology, We're Not Married. Moreover, it promoted her to the female lead of Roy Ward Baker's Don't Bother to Knock (both 1952), a reworking of Charlotte Armstrong's novel, Mischief, in which pilot Jed Towers (Richard Widmark) comes to suspect that elevator operator's niece Nell Forbes (Monroe) is not ideal babysitter material when he comes across her at the New York hotel where he is hoping to hook up with chanteuse Lyn Lesley (Anne Bancroft).

Unconvinced that Monroe had the personality or the technique to handle such a dramatically demanding role, Zanuck cast her as a streetwalker alongside Charles Laughton in Henry Koster's 'The Cop and the Anthem' segment of another portmanteau picture, O. Henry's Full House. He also backed her into playing the dumb blonde caricature of Lois Laurel in Howard Hawks's Monkey Business (both 1952), the secretary of scientist Dr Barnaby Fulton (Cary Grant) who looks on in bemusement after he and wife Edwina (Ginger Rogers) consume an elixir of youth that has been accidentally poured into a water cooler by a chimpanzee named Esther. Having packed 14 films into two years, however, Monroe was about to leave bit parts behind.

When Stocks are high, Mr President

It's strange to think that Marilyn Monroe was born six weeks after Princess Elizabeth of York and that each should have had her life transformed by events in 1953. Having ascended to the throne the previous year, Queen Elizabeth II was crowned in Westminster Abbey the day after Marilyn's 27th birthday. And the actress became Hollywood royalty a few weeks later, when she and Jane Russell were invited to leave their hand and foot prints in the forecourt cement outside Grauman's Chinese Theatre. But fame came at a price.

Monroe's big breakthrough came as femme fatale Rose Loomis in Henry Hathaway's Niagara (1953), which was one of the final films that Fox made in Technicolor before switching to CinemaScope. Shooting a brooding noir in colour was a bold step and Monroe's costumes were colour-coded to send out warning signals to both her war veteran husband, George (Joseph Cotten), and honeymooning hotel neighbours, Ray and Polly Cutler (Max Showalter and Jean Peters).

Monroe's previous characters hadn't always been on the straight and narrow, but Hathaway shrouded her in towels and bedsheets to contrast Rose cunning hussy with Polly's girl next door. Moreover, he had make-up artist Allan Snyder design a look that was at once modern, sensual and dangerous and Monroe retained the style for much of the decade. The critics were undecided, but women's groups protested at Rose's immorality and Joan Crawford accused Monroe of behaviour 'unbecoming an actress and a lady' when she attended the Photoplay awards to collect the prize for Fastest Rising Star in a tight gold lamé dress. The remark is all the more curious because Crawford is rumoured to have been one of the women (along with Barbara Stanwyck, Marlene Dietrich and Elizabeth Taylor) with whom Monroe slept, along with drama coaches Natasha Lytess and Paula Strasberg.

Lytess was deeply unpopular with Monroe's directors, as she tended to consult with her between takes about how she should play a scene. But Monroe also worked with actor Michael Chekhov and mime Lotte Goslar around this time and took her first steps towards Method acting when she spent time in a Monterey fish cannery while preparing to play a factory worker in Clash By Night.

For all her devotion to her craft, however, Monroe often struggled with her lines and frequently requested retakes in order to perfect her performance. Moreover, she gradually exhausted much of the goodwill she had with the cast and crew by keeping them waiting for hours on end because of her infamous time-keeping. It's clear these issues were rooted in the insecurities she had carried over from childhood. But time was money in Hollywood and, often receiving censure when she most needed support, Monroe was not alone in turning to pills and alcohol in a bid to cope with the stresses of stardom.

Despite her problems on and off the set, Monroe continued to give beguiling performances, even when called upon to essay characters whose intellect was way beneath her own. The part of Lorelei Lee in Anita Loos's novel, Gentleman Prefer Blondes, had originally been earmarked for Fox's long-standing golden girl, Betty Grable. But Zanuck felt the 35 year-old was too old to play the diamond-loving showgirl in Howard Hawks's 1953 musical rendition and cast Monroe alongside Jane Russell, as Lorelei's husband-hunting pal, Dorothy Shaw. However, Monroe was slowly learning how to play the game and supposedly insisted on the line, 'I can be smart when it's important, but most men don't like it,' being inserted into Charles Lederer's screenplay.

Grable had been one of Norma Jeane's idols and Monroe was delighted when she was teamed with her and Lauren Bacall in Jean Negulesco's How to Marry a Millionaire, as singletons Loco Dempsey, Schatze Page and myopic model Pola Debevoise take a lease on a Sutton Place penthouse in the hope of finding wealthy beaux. This was only the second feature that Fox had filmed in CinemaScope after Henry Koster's The Robe (both 1953) and it overcome a lukewarm critical response to become the biggest commercial success of Monroe's career to date.

However, her year ended with a bitter dose of reality. Neither she nor director Otto Preminger had wanted to make River of No Return, which Frank Fenton had scripted by melding together a Louis Lantz story and the core plot points of Vittorio De Sica's neo-realist masterpiece, Bicycle Thieves (1948). Consequently, they were both spoiling for a fight long before they reached the Canadian location outside Calgary.

Monroe had been cast as Kay Weston, a dance-hall singer in the American Northwest of the mid-1870s, who has been caring for abandoned nine year-old Mark Calder (Tommy Rettig) while his father, Matt (Robert Mitchum), was in prison for manslaughter. But she found the material dull and, in her attempt to understand her character, she relied heavily on Lytess. A furious Preminger ordered producer Stanley Rubin to have the coach removed, but Monroe went over his head to Zanuck and threatened to walk away unless Lytess was reinstated.

Monroe won the battle, but Zanuck was determnined not to let a hireling get the better of him. As she was still employed by the terms of her 1950 contract, he turned down all of her suggestions for weighty projects and attached her to another frothy musical comedy entitled The Girl in Pink Tights. When Monroe refused to report to the set in January 1954, Zanuck put her on suspension. She retaliated by marching Joe DiMaggio to San Francisco City Hall on 14 January to exchange vows and promptly sweeping him off on a honeymoon in Japan that enabled her to join a USO troupe in Korea and entertain 60,000+ Marines over four days.

She was greeted on her return with Photoplay's award for Most Popular Female Star and a new contract from Fox that not only upped her salary to $3000 per week, but also included a $100,000 bonus and a promise to headline Billy Wilder's forthcoming adaptation of George Axelrod's Broadway hit, The Seven Year Itch.

The only catch was that Monroe had to join Ethel Merman, Donald O'Connor and Dan Dailey in Walter Lang's There's No Business Like Show Business (1954), a backstager scripted by Phoebe and Henry Ephron (parents of writer-director Nora Ephron) that drew on the marvellous Irving Berlin songbook. Monroe did what was expected of her in the 'Heat Wave' number to justify the studio's decision to shoot in CinemaScope and DeLuxe colour for the first time. Yet Monroe never rated the film, even though O'Connor considered it the best thing he had ever done - and he had co-starred with Gene Kelly and Debbie Reynolds in Kelly and Stanley Donen's musical masterclass, Singin' in the Rain (1952).

The Reel Films of Marilyn Monroe

Very much a film of its time, The Seven Year Itch (1955) concerns an encounter between married New Yorker, Richard Sherman, and a single female neighbour known only as The Girl, which occurs after his wife and young son have gone away for the summer. Sherman's insinuations and fantasies may feel creepy to modern viewers, but the frankness of The Girl's attitudes towards sex and society would have seemed daringly revelatory to pre-permissive audiences confronted on all sides by taboos. In fact, playwright George Axelrod and director Billy Wilder had to battle hard with the Production Code Administration to get their screenplay vetted and several scenes deemed suitable for sophisticated theatregoers (including a sexual dalliance) were cut to avoid corrupting the cinema crowd.

Reprising his Broadway role, Tom Ewell earned a Golden Globe for his performance. But, in taking over the role created on stage by Vanessa Brown, Monroe failed to land a single nomination. Nevertheless, the image of The Girl's white dress billowing over a subway ventilator became instantly iconic, even though the two-hour shoot in front of a leering 2000-strong crowd outside the Trans-Lux 52nd Street Theatre on Lexington Avenue (where the pair had been to see Jack Arnold's The Creature From the Black Lagoon, 1954) led to a showdown between Monroe and a disapproving DiMaggio.

On returning to Los Angeles in October 1954, Monroe accused DiMaggio of being controlling and violent and filed for divorce after just nine months of marriage. A month later, she flexed her muscles again, when she teamed with photographer Milton Greene to form Marilyn Monroe Productions and announced that she no longer considered herself bound by her Fox contract because the studio had failed to honour its promise to pay her a bonus. As the dispute rumbled on, Axelrod ungallantly parodied Monroe in the character of Rita Marlowe in his 1955 play, Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? Fox clearly approved of the joke and bought the rights for director Frank Tashlin, who hired Jayne Mansfield to reprise her role. But the 1957 screen adaptation actually bears little resemblance to the original show.

Undaunted, Monroe decamped to New York, where she severed her ties with Natasha Lytess and enrolled at the Actors Studio, which was run by Lee and Paula Strasberg. Thanks to Marlon Brando, James Dean, Montgomery Clift and Paul Newman, Method acting had caught on in Hollywood and Monroe felt convinced the technique of drawing on personal experience to authenticate a character's emotions would help her shed her ditzy image and persuade directors that she was a serious artist.

With Paula now acting as her private coach, Monroe also entered psychoanalysis. She also started dating Marlon Brando. However, this proved a brief fling, as Monroe fell heavily for playwright Arthur Miller, who was in the process of divorcing first wife, Mary Slattery. Alarm bells sounded in Hollywood, however, when Monroe accompanied Miller to his appearance before the House UnAmerican Activities Committee investigating Communist connections in the enterainment world.

As a result, the FBI opened a file on Monroe, although she was free to continue working. Indeed, she had just signed a new contract with Fox that allowed her to select her own projects and directors, while also giving her the freedom to make occasional pictures for her own production company. The deal sent ripples through Hollywood and further weakened the grip that the studio system had exerted over its contract players since the 1920s.

In March 1956, Monroe chose rising Broadway talent Joshua Logan to direct her in Bus Stop, which George Axelrod had adapted from a play by William Inge. Although the role of the café singer who dreams of stardom required her to sing 'That Old Black Magic', Monroe believed that Cherie was very different to any character she had played before. In addition to her (relatively) deglamorised look, she also mastered an Ozarks accent and completely upstaged Don Murray as Beauregard Decker, the naive rodeo rider who falls head over heels.

Murray would receive Best Supporting Actor nominations at both the Academy Awards and the BAFTAs. But Monroe landed a Golden Globe nod for Best Actress and seemed to be in a good place after having married Miller on 29 June. By converting to Judaism, Monroe had her films banned in Egypt, while Variety sniped at the couple's perceived intellectual mismatch by running the headline, 'Egghead Weds Hourglass.' But Monroe at last seemed to be happy and was taking control of her destiny.

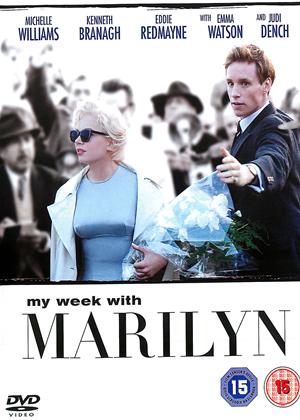

As is clear from Simon Curtis's My Week With Marilyn (2011) - which is based on aspiring film-maker Colin Clark's memoir of the shoot - Monroe endured a torrid time at Pinewood Studios, as Olivier proved to be an unsympathetic director. Frustrated by Monroe's trademark tardiness, he deeply resented the presence of both Paula Strasberg and Arthur Miller, who kept finding fault with the script. However, it was Monroe's difficulty in hitting her marks and delivering her lines that prompted Olivier to insult her and Monroe to withdraw her co-operation.

Remarkably, however, the production wrapped on schedule and not only earned Monroe a BAFTA nomination for Best Foreign Actress, but also earned her Italy's prestigious David di Donatello Award and France's Crystal Star. Following some mediocre notices, the film underwhelmed at the US box office and Monroe decided to take an 18-month break to forget Hollywood and start a family.

Sadly, she suffered both an ectopic pregnancy and a miscarriage during 1957, while Miller also had to call paramedics following a September overdose. A later miscalculation required a stomach pumping and Monroe started to consult psychoanalysts Marianne Kris and Ralph Greenson to help her negotiate daily life. Yet she decided to return to work in July 1958 and was teamed with Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon in Some Like It Hot (1959), Billy Wilder's reworking of Kurt Hoffman's Fanfaren der Liebe (1951), which was itself a remake of Richard Pottier's Fanfare d'amour (1935).

The story of two male musicians who drag up after witnessing a gangland killing in 1920s Chicago has become a much-loved classic. Monroe's rendition of 'I Wanna Be Loved By You' became a hit. But she felt that Sugar Kane was another dumb blonde, even though Miller thought Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond's script had merit.

The offer of 10% of the profits proved a further incentive. But the shoot wasn't a happy one, with Curtis being so fed up with Monroe's lateness that he told one reporter that their on-camera clenches were 'like kissing Hitler'. Tired of competing with Paula Strasberg, Wilder despaired of Monroe's reluctance to take direction and her constant need for retakes. Indeed, he noted sardonically, 'Anyone can remember lines, but it takes a real artist to come on the set and not know her lines and yet give the performance she did!'.

Nevertheless, Monroe won the Golden Globe for Best Actress in a Musical or Comedy and her star burned brightly again. Following another short hiatus, she hoped to return to the screen in a drama that Miller had written specially for her. But, as she still owed 20th Century-Fox a film according to the terms of her improved contract, she agreed to headline George Cukor's Let's Make Love (1960).

In fact, screenwriter Norman Krasna had hoped to pair Gregory Peck and Cyd Charisse in the story of a pompous playboy who discovers he's being lampooned in a musical show. But Peck dropped out when Monroe was cast as Amanda Dell and Cary Grant, Charlton Heston and Rock Hudson all declined the chance to be her co-star. Eventually, Yves Montand, who had co-starred with wife Simone Signoret in Raymond Rouleau's 1957 adaptation of Arthur Miller's HUAC allegory, The Crucible (which was filmed in 1996 by Nicholas Hytner, with Daniel Day-Lewis and Winona Ryder) signed up to play Jean-Marc Clément, even though he couldn't speak English.

As life on the set became inevitably complicated and Monroe began going AWOL, rumours started circulating that the leads were having an affair. However, Montand returned to Signoret after the picture wrapped and Monroe announced she was moving on to the film that had been scripted by her husband. One of Miller's friends, Truman Capote, had become intrigued by Monroe and lobbied for her to play Holly Golightly in Blake Edwards's adaptation of his celebrated novella, Breakfast At Tiffany's (1961). But Paramount insisted on casting its own leading star, Audrey Hepburn, and Monroe lost a role that might have confirmed her dramatic talent in the eyes of the often sceptical critics. Instead, she set off for Dayton, Nevada for what would turn out to be her last completed film.

The Sad End and Beyond

Cinema Paradiso has already covered John Huston's The Misfits (1961) in some detail in one of its What to Watch If You Like articles. As a girl, Monroe had daydreamed that Clark Gable was her real father and she doted on him while filming this latterday Western, in which 30 year-old Roslyn Tabor (Monroe) and her Reno landlady Isabelle Steers (Thelma Ritter), befriend ageing cowboys Gay Langland (Gable), Guido (Eli Wallach) and Pierce Howland (Montgomery Clift) while Roslyn awaits her divorce.

Conditions were often arduous during the desert shoot that ran from July to November 1960 and Monroe's mood dipped when it became apparent that her marriage was over. Indeed, Miller fell in love with photographer Inge Morath when she visited the set and Monroe became so distressed that Huston closed down the production in August while his star underwent rehabilitation.

The picture wrapped on 4 November, only for Gable to suffer a cardiac arrest two days later. He seemed to be recovering when Monroe announced her separation from Miller on 11 November. But Gable suffered a second attack five days later and Monroe was crushed when widow Kay Ashby blamed her behaviour on location for making her husband so tense. When The Misfits opened on what would have been Gable's 60th birthday on 1 February 1961, Monroe was being treated at the Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic on New York's 68th Street under the name of Faye Miller.

Marianne Kris had persuaded her to submit herself, as she had feared another suicide attempt was in the offing. But Monroe quickly realised that she had been incarcerated and threatened to slash her wrists on a broken window unless she was released. When neither Kris nor Lee Strasberg answered her pleas for help, Joe DiMaggio secured her release and press speculation about a reconciliation grew when she accompanied him to Florida for Yankees spring training. Once again, however, DiMaggio's possessive side clashed with Monroe's free spirit and they drifted apart after she started partying with the Rat Pack.

Monroe had known Peter Lawford for some time, but he was now the brother-in-law of the President of the United States, as he had married John F. Kennedy's sister, Patricia. Lawford's membership of the Pack irritated the White House, however, as Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy wanted to strike against organised crime and Frank Sinatra was associated with leading gang boss Sam Giancana.

Monroe found herself co-starring with another of Sinatra's inner circle after NBC cancelled her TV debut in W. Somerset Maugham's Rain (which Lewis Milestone had filmed with Joan Crawford in 1932) and she was cast opposite Dean Martin in George Cukor's Something's Got to Give. This was a remake of Garson Kanin's My Favorite Wife (1940), in which Irene Dunne had played the shipwreck victim who returns home after seven years to discover that husband Cary Grant has had her declared dead and remarried.

After a year away from the screen, armed with the Golden Globe for World Film Favourite and newly installed in 12305 Fifth Helena Drive in the Brentwood district of Los Angeles, Monroe seemed enthusiastic about the project. Having lost weight following a gallstone operation, she contemplated making Hollywood history by becoming the first A list star to appear naked in a major movie. However, she was absent for much of the first month of shooting with bouts of sinusitis and bronchitis.

Much to the surprise of the Fox front office, Monroe kept a promise to sing 'Happy Birthday' to JFK at New York's Madison Square Garden on 19 May and she returned to the set eager to film her swimming pool scene. In order to generate advance publicity, photographs of Monroe in the water were published in Life magazine. But events would conspire to ensure that Jayne Mansfield would become the first mainstream star to go topless in the sound era in King Donovan's Promises! Promises! (1963).

Monroe celebrated her 36th birthday with the cast and crew. But Cukor convinced the studio to sack her when she promptly reported sick again and, with Joseph L. Mankiewicz's Cleopatra (1963) already depleting its coffers, Fox closed the picture down and sued Monroe for $750,000 in damages. When Kim Novak and Shirley MacLaine refused to replace her, Lee Remick accepted the challenge, only for Dean Martin to resigned and be sued by Fox.

When the studio revived the project as Move Over, Darling (1963), Doris Day was teamed with James Garner under the direction of Michael Gordon. Curiously, MacLaine did later take up an unrealised Monroe project, when she was surrounded by guest stars Gene Kelly, Dean Martin, Paul Newman and Robert Mitchum in J. Lee Thompson's What a Way to Go! (1964). Moreover, Michael Gordon took over another film that had been previously linked with Monroe, when he directed Carroll Baker in Harlow (1965).

Norma Jeane's favourite film star, Jean Harlow had died at the age of 26 on 7 June 1937. By a cruel twist of fate that was the very day on which Fox fired Monroe and cynically started a whispering campaign in the press about her mental health. She fought back with interviews in Life and Cosmopolitan and even made her debut in Vogue . In addition to the fashion shots, Monroe also posed nude for photographer Bert Stern, who gathered the images for his 1982 book, The Last Sitting.

What happened next has been the subject of endless speculation and Cinema Paradiso users can hear some of the arguments in such documentaries as Patty Ivins Specht's Marilyn Monroe: The Final Days (2001), James Younger's Conspiracy Theories: The Death of Marilyn Monroe (2006) and Arthur Pierson's Marilyn Monroe: Memories and Mysteries (2009). What seems incontrovertible is that photographer George Barris took the last professional shot of Monroe on 13 July 1962, although her final interview was conducted by Life's Richard Meryman on Friday 3 August. The next day, she asked Ralph Greenson to pay a house call after she had supposedly been warned off the Kennedy brothers by a family friend. He subsequently claimed to have left her feeling calmer in the care of her housekeeper, Eunice Murray.

Around 8pm, Monroe decided to have an early night and played Sinatra records while calling friends. At 3am, Murray woke up and went to check on Monroe. She was surprised to see a light coming from under the bedroom door, which was locked. Unable to get an answer, Murray called Greenspan, who broke a window to gain admittance and found Monroe lifeless on the bed, with the phone receiver gripped in her right hand. He also spotted a piece of paper bearing the White House phone number and several pill bottles scattered around the room.

Personal physician Hyman Engelberg pronounced Monroe dead at 3:50am and the Los Angeles police were called around 4:25am. It was established that she had died between 8:30 and 10:30pm on 4 August from acute barbiturate poisoning, with the dosages convincing deputy coroner Thomas Noguchi to declare a probable case of suicide.

Joe DiMaggio claimed Monroe's body and organised the funeral at the Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery, which was attended by only 25 mourners. Lee Strasberg was among them, along with her half-sister Berniece Baker Miracle. But DiMaggio barred anyone he felt had contributed to his ex-wife's downfall. For over 20 years, he sent a dozen red roses to Crypt No. 24 at the Corridor of Memories, as tributes continued to pour in and conspiracy theories started to swirl.

A year after Monroe featured in Jack Haley, Hollywood: The Fabulous Era (1962), Fox rushed out Marilyn (1963), a Rock Hudson-narrated documentary that had been directed by Harold Medford to highlight the crucial role that the studio had played in her career. The following year, John Huston provided the voiceover for Terry Sanders's The Legend of Marilyn Monroe, which was shelved for over three decades, despite the fact it contained some previously unseen footage and interviews with the people who had known her best.

Cinema Paradio users can rent this important document, along with Marilyn Monroe: Beyond the Legend (1987), Marilyn Monroe: A Life in Pictures (2005) and Marilyn Monroe: In the Movies (2012). Also worth checking out are Nicolas Roeg's Insignificance (1985), in which Theresa Russell plays a Monroe-like actress; Tom Fywell's Norma Jean and Marilyn (1996), starring Ashley Judd and Mira Sorvino; and Joyce Chopra's Blonde (2001), a mini-series with Poppy Montgomery that was based on Joyce Carol Oates's bestselling novel about Monroe.

Much has been said and written about Monroe in the 60 year since her candle burned out. Yet she remains elusive and her lasting cultural significance has yet to be confirmed. Regardless of the political shifts that influence academic assessments of her life and achievement, her films continue to entertain and beguile. As Bernie Taupin once put it, she will always be'more than just our Marilyn Monroe'.