This year marks the centenary of one of the most distinctive stars in Hollywood history. He received 10 Oscar nominations over five decades in amassing over 80 screen credits. But there was much more to Paul Newman than his acting, as Cinema Paradiso reveals.

Despite being one of the most iconic stars of the New Hollywood era, Paul Newman didn't rate himself as an actor. He once claimed he was nothing more than 'an untuned piano' who had been cursed with a handsome face and piercing blue eyes. 'I was always a character actor,' he once explained, 'I just looked like Little Red Riding Hood.'

Writer Gore Vidal compared his close friend to Gary Cooper and Henry Fonda when it came to screen acting: 'They are so good no one knows they are any good.' Screenwriter William Goldman was clearly thinking along similar lines when he opined, 'He could be called a victim of the Cary Grant syndrome. He makes it look so easy, and he looks so wonderful, that everybody assumes he isn't acting.'

Newman often claimed that his greatest gift was having luck. For all his self-deprecation, however, he took his craft very seriously, as he did his marriage, his motor racing, his political activism, his foodie enterprises, and his philanthropy. He might not always have got things right, but he tried to make a difference and both his achievements and his centenary are well worth celebrating.

From the Heights

Rather fittingly, Arthur Newman and Theresa Fetzer met at a cinema in Cleveland, Ohio. She worked there, while he helped run the family sporting goods store. A year and three days after the arrival of Arthur, Jr., Paul Leonard Newman was born in Cleveland Heights on 26 January 1925.

As the shop flourished, the family moved to the affluent neighbourhood of Shaker Heights, where the young Paul's interest in the arts was encouraged by Theresa and his uncle, Joseph Newman, who was a well-known journalist and poet. At seven, he played the court jester in a school production of Robin Hood, and, three years later, he slew the dragon in a play about St George at the Cleveland Play House, where he also joined the Curtain Pullers children's theater group.

Looking back, Newman resented his mother fussing over him. 'As a child,' he recalled, 'I might do something cute or come downstairs looking especially pretty, wearing little shirts and a sweater, and she revelled in the great flood of emotion that flowed through her, whether it was tears or joy. The child himself was not really seen.'

Distrusting his mother's motives for favouring him, Newman also felt that his father was dismissive and disinterested. 'I got no emotional support from anyone,' he later claimed. As he never excelled at school, he came to believe 'I never gave my father anything to be proud of,' although Arthur did approve of his son earning money by 'making deliveries for the florist and the dry cleaner, carting pickle barrels and Coca-Cola cases up and down stairs for the delicatessen' and by selling brooms door to door.

Despite being a star player on the football, basketball, and baseball teams at Shaker Heights High School, the teenage Newman preferred to spend his afternoons shooting pool and chugging beer. He later confided to writer friend Stewart Stern that he was a 'lightweight' at school. 'I wasn't naturally anything. I wasn't a lover. I wasn't an athlete. I wasn't a student. I wasn't a leader.' Nevertheless, after spending the summer selling encyclopaedias door to door, he secured a place at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio and would have stayed the course had the Second World War not intervened.

Joining the US Navy in 1943, Newman enrolled in the V-12 pilot training programme at Yale University, only to be cut after tests revealed he was colour blind (when, in fact, he wasn't). After going through basic training at boot camp, he became a radio operator and rear-gunner and was assigned to a torpedo bomber squadron at Barbers Point, Hawaii. Aviation Radioman Third Class Newman flew several missions as a turret gunner. However, when his unit was assigned to the aircraft carrier, Bunker Hill, on the eve of the Battle of Okinawa in 1945, his plane was grounded because the pilot was suffering from earache. Days later, the carrier was hit by a kamikaze plane, with the loss of hundreds of lives.

Service life proved an eye-opener in many ways. Newman had experienced a degree of anti-Semitism in Shaker Heights, as he had decided to follow after his Jewish father ('because it's more of a challenge') rather than his mother, who had abandoned Roman Catholicism to become a Christian Scientist. Indeed, he had been aware of a 'strong sense of otherness' throughout his youth and the fact that certain avenues were closed to him because of his identity. In the Navy, however, he got into a 'bloody fight' with a sailor who had used an anti-Semitic insult and this readiness to stand his ground would become a key facet of Newman's personality and his political thinking.

Returning to Civvy Street in 1946, the 21 year-old took advantage of the GI Bill to study economics at Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio. Once again, he found himself on the football team until 'there was sort of a brawl that we sort of got involved in where several of us ended up in the clink. As I result I was then off the football squad. Since I had to do something with my time, I started acting.'

Adding drama to his course, Newman graduated in 1949. Despite an acclaimed performance in The Front Page, he was under no illusions about his ability. 'I was probably one of the worst college actors in history,' he later protested. 'I had no idea what I was doing. I learned my lines by rote and simply said them, without spontaneity, without any idea of dealing with the forces around me on stage, without knowing what it meant to act and react.' Yet, he applied to join a summer stock company and stints followed with the Belfry Players in Wisconsin and the Woodstock Players in Woodstock, Illinois. He remained with the latter into 1950, appearing in 16 plays, including Cyrano de Bergerac and Dark of the Moon, which helped sharpen his skills and give him a taste for the theatrical life. Nevertheless, he found it difficult being in front of an audience. 'You have to learn to take off your clothes emotionally on stage,' he later recalled, 'I was lousy. I couldn't let go yet I wanted to act.'

In John Loves Mary, Newman was cast opposite Jackie Witte. They married in 1949 and had three children - Scott, Stephanie, and Susan - which put paid to Jackie's acting ambitions. Newman reached his own crossroads when his father died in 1950 and he returned home to help out with the sports shop. Feeling trapped, however, he signed over his share to his brother and (without telling Jackie) applied to study at the Yale School of Drama. He later admitted that he was inspired less by a burning desire to act than a desperation to flee the conformity that shop life would have brought. After completing the course, Newman found digs on Staten Island and set out to conquer New York.

Lucky Breaks

Newman had gone to Yale to major in directing and had expected to return to Kenyon to teach. As he later claimed, his main aim was to get out of Shaker Heights ('I was running away from something. I wasn't running towards.'). However, he was spotted in a production by a talent agent, who suggested that he tried his hand at television.

He got off to an inauspicious start with an uncredited bit in a 1952 episode of the sitcom, The Aldrich Family (1949-53), before receiving his first credit, as Sgt Wilson, in the 'Ice From Space' episode of the sci-fi series, Tales of Tomorrow (1951-53). Slots cropped up on various drama showcases, as well as on such series as Suspense, The Web, The Mask, and The Man Behind the Badge. Intriguingly, he also landed the lead in 'The Fate of Nathan Hale', an episode of Walter Kronkite's history re-enactment show, You Are There (1953-72), which was directed by Sidney Lumet.

While the majority of these performances have long been forgotten, one was noticed by Broadway director Joshua Logan, who gave Newman his Broadway debut as Alan Seymour in his production of William Inge's Picnic (which Logan filmed in 1956 ). The play won the Pulitzer Prize and ran for 14 months, by which time Newman had taken over the leading role from Ralph Meeker, whom he had been understudying.

During the run, Newman attended classes at the Actors Studio, which had been founded by Lee Strasberg. Karl Malden, Ben Gazzara, Julie Harris, and James Dean were among his classmates, while Marlon Brando would occasionally drop in when not developing his take on Method acting with Stella Adler. Newman always claimed, 'I learned everything I've learned about acting from the Actors Studio.' But, as he claimed to have been blocked off from his emotions, he took a cerebral approach to building characters that owed more to Adler than Strasberg. By striving to understand a character's life, Newman was able to inhabit rather than interpret roles and this led some critics to claim that he often didn't appear to be acting at all.

Surrounded by so many driven people, however, Newman suffered from self-doubt. 'I never had a sense of talent,' he later said, 'because I was always a follower, following someone else with stuff that I basically interpreted and did not really create.' But he found a champion in a fellow understudy, who had taken an instant dislike to him when they had first met in the office of agent Maynard Morris. Being forced together in the wings each night, however, Newman and Joanne Woodward became friends and, as

they joked around behind the scenes and she tried to teach him how to dance, they started an affair that would last for almost five years before Newman finally asked Witte for a divorce.

In 1954, Warner Bros offered Newman a five-year contract with a starting wage of $1000 a week. He was tested alongside James Dean for East of Eden (1955), but director Elia Kazan had not been overly impressed by Newman at the Actors Studio and he had to settle instead for a screen debut as Basil, the maker of the cup used at the Last Supper, in Victor Saville's Biblical saga, The Silver Chalice (1954). The reviews were scathing and Newman was so ashamed of his sole outing in a toga (which he called 'a cocktail dress') that when it was shown on television in Los Angeles in 1963, he took out a black-edged announcement in the local press that read: 'Paul Newman apologises every night this week - Channel 9.'

His mood was not improved by a brush with producer Sam Spiegel, who was casting Elia Kazan's On the Waterfront (1954). He suggested that Newman should change his surname, as it sounded too Jewish. Seizing on the fact that Spiegel occasionally used the credit, 'S.P. Eagle', Newman demanded to know whether he should go by 'S.P. Ewman'?

Eager to get out of Hollywood, Newman asked his agent to find him a play in New York and he made such a good job of leading a gang of house invaders in The Desperate Hours that Humphrey Bogart wanted the part when William Wyler adapted it for the screen in 1955. More television assignments followed, including the lead in Gore Vidal's The Death of Billy the Kid and the role of teenager George Gibbs opposite Frank Sinatra and Eva Marie Saint in a musical version of Thornton Wilder's Our Town (both 1955). Newman had landed the latter as a late replacement for James Dean. But his car crash death on 30 September meant that Nick Adams became Newman's co-star in an Arthur Penn-directed teleplay based on the Ernest Hemingway short story, The Battler.

MGM was so impressed by Newman's performance as a punch-drunk pug that the studio borrowed him for Dean's role as Rocky Graziano in Robert Wise's boxing biopic, Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956), and further sporting roles followed on the small screen in Bang the Drum Slowly (1956) and The 80 Yard Run (1958). Newman was also slotted into the role that Glenn Ford had vacated of a soldier facing a court martial in Arnold Laven's The Rack (1956).

Feeling that Newman had been swindled out of an Academy Award nomination for his performance as Rocky Graziano, Wise presented the actor with a 'Noscar'. But Warners had yet to be convinced by their new star, despite teaming him with Ann Blyth in Michael Curtiz's The Helen Morgan Story, a Prohibition-era showbiz biopic that required Newman to turn on the charm as bootlegger Larry Madux romancing the eponymous singing star. As a result, they were happy to loan him out to Robert Wise again for Until They Sail (both 1957), in which American airman Captain Jack Harding becomes involved with a war widow (Jean Simmons) in 1940s New Zealand. This monochrome CinemaScope drama isn't currently on disc in the UK, but it taught Hollywood that Newman wasn't a conventional leading man and that he was better suited to mavericks than romantics.

New Man in Town

While Warners didn't quite know what to do with its new star, other studios did and were willing to pay a $75,000 loan fee in order to secure Newman's services. As he was raking in a weekly $17,500, he was more than happy to go to 20th Century-Fox to co-star with Joanne Woodward in Martin Ritt's The Long, Hot Summer (1958), which had been adapted from three short stories by William Faulkner. Newman played drifter Ben Quick, who arrives in a Mississippi town and draws the attention of bigwig Will Varner (Orson Welles), who sets about matchmaking him with his daughter, Clara (Woodward). Working on location proved too much for the couple and they went public with their romance before marrying later in the year. They would make 15 further films together, even though Newman always felt inferior to his new wife when it came to performing. 'Some people are born intuitive actors,' he claimed, 'and have the talent to slip in and out of the characters they are creating. Acting to me is like dredging a river. It's a painful experience.'

Nevertheless, Newman won Best Actor at the Cannes Film Festival and returned to his home studio to reprise the role of William Bonney in Arthur Penn's The Left Handed Gun. In fact, Billy the Kid wasn't left handed and the Production Code outlawed screenwriter Gore Vidal's attempts to put a gay subtext on his relationship with Sheriff Pat Garrett (John Dehner). But the reviews were positive, as they were for another picture in which the gay undercurrent was expunged, Richard Brooks's adaptation of Tennessee Williams's Pulitzer Prize-winning play, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (both 1958). The camera couldn't help but focus on the respective blue and lilac eyes of Newman and Elizabeth Taylor, as Brick Pollitt and Maggie the Cat struggled to resolve their marital difficulties. Each earned Oscar nominations, but the critical consensus has since been that Newman's brand of Method acting lacked the emotional flexibility to enable him to convey the inner feelings of such conflicted characters.

That said, in spite of Fox pairing him with Woodward, Newman proved ill at ease as a comic lead in Leo McCarey's Rally Round the Flag, Boys (1958), which saw Angela Hoffa (Joan Collins) attempt to break up the marriage of publicist Harry Bannerman and his civic-spirited wife, Grace. Back at Warner, Newman was no more comfortable as Tony Lawrence coping with a chip on his shoulder in pursuing socialite Joan Dickinson (Barbara Rush) in The Young Philadelphians, Vincent Sherman's take on a Richard P. Powell potboiler. Newman detested the project (even though his mother thought he had much in common with Tony) and tried to hire Dalton Trumbo to rework James Gunn's script without knowing that he was merely acting as a front for the blacklisted screenwriter.

Newman only endured the shoot because Warners had promised that he could take time off from his contract to return to Broadway to partner Geraldine Page in Tennessee Williams's Sweet Bird of Youth. They proved so effective as gigolo Chance Wayne and fading film star Alexandra Del Lago that MGM recruited them when Richard Brooks directed the screen version in 1962. Being back in New York suited Newman and he and Woodward moved into a carriage house on the Upper East Side, where they became the centre of a chic social circle. Although they would acquire a property in California and keep an apartment in New York, they would later base themselves in a converted barn in Westport, Connecticut.

The couple took themselves back to Hollywood for Mark Robson's adaptation of John O'Hara's novel, From the Terrace, which sees US Navy veteran David Alfred Eaton turn his back on his parents (Myrna Loy and Leon Ames) to marry into the wealthy family of Mary St John. Typical of the kind of earnest soap opera that Hollywood favoured around this period to kick against the restrictive Production Code, the drama so frustrated Newman that he spent $500,000 to cancel his contract with Warners so that he could select his own projects. The first was Otto Preminger's Exodus (both 1960), an adaptation of a Leon Uris novel that follows Haganah rebel Ari Ben Canaan, as he takes a cargo boat full of Holocaust survivors from an internment camp in Cyprus to Mandatory Palestine.

Newman and Preminger had argued throughout the shoot, with the director needing medical treatment after the actor had pranked him by tossing a lookalike mannequin off a balcony at the end of a scene. However, he had much more fun learning to play the trombone for Martin Ritt's Paris Blues, a potent study of race relations that sees Ram Bowen and saxophonist Eddie Cook (Sidney Poitier) fall for tourists Lillian Corning (Joanne Woodward) and Connie Lampson (Diahann Carroll) while playing in a city with a relaxed attitude to integration. He also relished picking up tips from pool ace Willie Mosconi to perfect his performance as 'Fast Eddie' Felson seeking to take down George 'Minnesota Fats' Hegerman (Jackie Gleason) in Robert Robert Rossen's The Hustler (both 1961). Bristling with attitude, Newman finally emerged from the shadows of Brando and Dean with this Oscar-nominated, BAFTA-winning performance.

Curiously, however, he didn't kick on from this breakthrough, partly because he had a career-long misfortune of working with major directors on some of their least memorable films. Newman himself had experimented behind the camera with On the Harmfulness of Tobacco (1962), a little-seen short featuring Actors Studio classmate, Michael Strong, delivering Anton Chekhov's monologue. But his focus, for the moment, remained on acting.

Revisiting The Battler, Newman again played boxer Ad Francis in Martin Ritt's Hemingway's Adventures of a Young Man (1962), which he followed by reuniting with Woodward on Melville Shavelson's A New Kind of Love (1963), a rather dated romcom in which tomboy Sam Blake has a glamorous makeover to teach chauvinist newspaper columnist Steve Sherman a lesson. J. Lee Thompson's What a Way to Go! (1964) was little better, as Newman guested as Larry Flint, the avant-garde artist who is just one of the many lovers of Louisa May Foster (Shirley MacLaine) to meet a sticky end.

Newman then tried to reinvent himself as a Cold War thriller hero, alongside Elke Sommer in Mark Robson's The Prize (both 1963) and Julie Andrews in Alfred Hitchcock's Torn Curtain (1966). Each film had its suspenseful moments, but Newman seemed disengaged, which was very much not the case with Martin Ritt's Hud (1963). Adapted from a novel by Larry McMurtry, this simmering drama saw Hud Bannon disappoint his cattle-ranching father, Homer (Melvyn Douglas), with his slothful arrogance and disrespectful attitude towards housekeeper Alma Brown (Patricia Neal). Made for Ritt and Newman's Salem Productions, this bruising drama earned Oscars for both Neal and Douglas, while Newman lost out for his portrayal of a man with a 'barbed-wire soul' to Sidney Poitier in Ralph Nelson's Lilies of the Field.

Perhaps the most peculiar film of his entire career was Martin Ritt's The Outrage (1964), a remake of Akira Kurosawa's Rashomon (1950) that cast Newman as Mexican bandit, Juan Carrasco, alongside Laurence Harvey and Claire Bloom as the married couple, Edward G. Robinson as a shifty con man, William Shatner as a disillusioned preacher, and Howard Da Silva as a failed prospector. There were also plenty of flashbacks in Peter Ustinov's Lady L (1965), as Lady Lendale (Sophia Loren) reminisces about her lovers, including Newman's Armand Denis.

Neither film did much for Newman's stalling reputation and he was glad to arrest the slide with Jack Smight's Harper (1966), which was adapted by William Goldman from Ross Macdonald's novel, The Moving Target. As Lew Harper, the Los Angeles private eye hired to find a missing millionaire, Newman combined cynicism and charisma, as he rubs shoulders with the likes of Lauren Bacall, Julie Harris, Robert Wagner, Janet Leigh, and Shelley Winters. He would reprise the role in Stuart Rosenberg's The Drowning Pool (1975), which took Harper to Louisiana at the behest of an old lover (Joanne Woodward), who is being blackmailed by her former chauffeur.

Having written The Long, Hot Summer and Hud, the married team of Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank, Jr. bade farewell to Newman by adapting Elmore Leonard's Hombre for Martin Ritt, who was also making the last of his six collaborations with the actor. Although he has little dialogue, John Russell, an Apache-raised white man facing prejudice during a stagecoach ride across 19th-century Arizona, exudes the rectitude and dignity of the Civil Rights leaders who Newman and Woodward admired so much. Indeed, he would be one of the narrators of the epic documentary, King: A Filmed Record...Montgomery to Memphis (1970).

Although not a fan of pop music, Newman found himself installed as an icon of the counterculture after his performance as Lucas Jackson in Stuart Rosenberg's prison classic, Cool Hand Luke (1967), in which Newman delivered a line that became anthemic as American youth began to challenge the established order: 'What we've got here is a failure to communicate.' With its famous egg-eating sequence helping Newman to a fourth Oscar nomination for Best Actor, he reunited with Jack Smight for The Secret War of Harry Frigg (1968). Lightning didn't strike twice, however, as Newman's reluctant combattant strives to free some Allied soldiers from a luxurious Italian POW camp.

The critics were much kinder to Newman's feature debut behind the camera, however. Adapted by Stewart Stern from Margaret Laurence's novel, A Jest of God, Rachel, Rachel (1968) chronicles the sexual awakening of a shy Connecticut teacher in her mid-thirties. Woodward and Newman would win Golden Globes for their work, while she would also be nominated for an Oscar on the night that Carol Reed's Oliver! pipped this poignant and impeccably made drama to Best Picture. Not a bad return, considering that Newman hadn't liked the book and had only agreed to direct when his wife couldn't find anybody else.

Who Are Those Guys?

Jack Lemmon was originally offered the role of Sundance in George Roy Hill's Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). Warren Beatty had also distanced himself because he felt that William Goldman's screenplay owed too much to Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde (1967). But Steve McQueen agreed to partner Newman as the roguish leaders of the Hole in the Wall Gang, only for the pair to fall out and Robert Redford to step into the breach. He had such happy memories of the experience that he named his film festival after his character. Newman also enjoyed himself, having to come up with his own tricks during the bicycle sequence to 'Raindrops Keep Fallin' on My Head' because Hill had been unimpressed with the stunt rider. He later admitted that they should have thought more carefully about the ending, as he believed 'those two guys could have gone on forever'.

Goldman, cinematographer Conrad Hall, and composer Burt Bacharach all won Oscars, with the latter taking Best Song and Best Score. But the award for Best Picture went to John Schlesinger's Midnight Cowboy (1969), although that didn't stop Newman from later inviting Dustin Hoffman (and also Steve McQueen) to join him, Sidney Poitier, and Barbra Streisand in First Artists, a production company that aimed to make quality pictures on modest budgets. Unfortunately, Newman's contributions, Stuart Rosenberg's Pocket Money and John Huston's The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean (both 1972), fared badly and even The Drowning Pool was less successful than its predecessor.

Indeed, the 1970s got off to an indifferent start for Newman, with projects like Stuart Rosenberg's WUSA (1970) and Newman's own Sometimes a Great Notion (1971) failing to find critical or commercial favour. Centring on a white supremacist radio station in New Orleans, the former was Newman's personal favourite ('the most significant film I've ever made and the best'), while he also enjoyed playing Henry Fonda's son in the latter story about a logging family refusing to join a strike.

Newman remained behind the camera to direct Woodward in The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds (1972), which drew on a Pulitzer-winning Paul Zindel play about an overbearing mother raising her two daughters, one of whom was played by the couple's own child, Nell Potts. Woodward won the Best Actress prize at Cannes. but Newman's misfiring streak as an actor continued with John Huston's The Mackintosh Man (1973), an adaptation of the Desmond Bagley thriller, The Freedom Trap, that sees jewel thief Joseph Reardon turn secret agent in a bid to expose a Soviet spy ring in London.

George Roy Hill had declined the chance to direct the Newman lumber picture that had been based on a novel by Ken Kesey. But he bore no grudges and reunited with the director and Robert Redford on The Sting (1973). Complete with a score of old Scott Joplin ragtime hits played by Marvin Hamlisch, the tale of how 1930s gamblers Henry Gondorff and Johnny Hooker fleeced gangster Doyle Lonnegan (Robert Shaw) was a huge hit and won the Academy Award for Best Picture. Raking in $68 million, it was also the highest-grossing film of 1974, which made Newman a pretty percentage profit on top of his $500,000 fee.

Newman's happy knack of summoning up a hit when he most needed it had put him back on top of the Hollywood A list and he cashed in by starring with Steve McQueen in John Guillermin's disaster epic, The Towering Inferno (1974). In addition to a $1 million pay day, Newman also received a percentage of the $55 million gross, which made him the best-paid star in Tinseltown. Apart from the odd spat, he and the temperamental McQueen rubbed along well enough as architect Doug Roberts and San Francisco fire chief Michael O'Hallorhan atop an all-star cast list that also included William Holden, Faye Dunaway, Fred Astaire, Richard Chamberlain, Robert Vaughn, Robert Wagner, and, in her screen farewell, Jennifer Jones.

Frustratingly for Newman, this turned out to be his last success of the decade, as he had the misfortune to headline two rare Robert Altman misfires, as William Cody in Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson (1976) and as Essex, a seal hunter facing a new ice age, in the sci-fi curio, Quintet (1979). Critics were also taken aback by the coarseness of George Roy Hill's Slap Shot (1977), which cast Newman as Reggie Dunlap, an ice hockey player who is prepared to do whatever it takes to ensure a victory for the Charlestown Chiefs. Newman, however, saw the bruising Rust Belt saga in a different light. 'It's one of my favourite movies,' he revealed 'Unfortunately, that character is a lot closer to me than I would care to admit - vulgar, on the skids.'

Lucrative Sidelines

In 1969, Newman took the role of Frank Capua in James Goldstone's motor-racing drama, Winning. Being of the Method persuasion, Newman underwent an intense training programme with ace drivers Bob Sharp and Lake Underwood and became hooked on the sport. Such was his interest that he agreed to return to television to narrate David Winters's racing documentary, Once Upon a Wheel (1971).

Turning down film projects, Newman worked with instructor Bob Bondurant so he could reach racing standard. As he later explained, 'The show gives me a chance to get close to a sport I'm crazy about, I love to test a car on my own, to see what I can do, but racing with 25 other guys is a whole different thing. There are so many variables, the skill demanded is tremendous.' Thrilled to find 'the first thing that I ever found I had any grace in', he used the name 'P.L. Newman' to enter his first race at Thompson International Speedway in 1972.

For almost two decades, he drove for the Bob Sharp Racing team in the Trans-Am Series and won four championships. He also finished second in Dick Barbour's Porsche 935 at the 1979 edition of the 24 Hour race at Le Mans. Woodward fretted about his competing in such a dangerous sport. But, at the age of 70 years and eight days, Newman became the oldest winning driver a major sanctioned race, when his team won its class at the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1995.

In addition to his own endeavours on the track, Newman also formed a Can-Am team with Bill Freeman, which won the championship in 1979. Further success came with Carl Haas and the Newman/Haas Champ Car team, which took eight drivers' titles in the 1980s before the actor took a tilt at the NASCAR circuit. Newman even managed to combine his job and his hobby by cameoing as himself at the wheel in Mel Brooks's Silent Movie (1976), narrating the IMAX documentary, Super Speedway (1997), and voicing the character of Doc Hudson in John Lasseter's Pixar classics, Cars (2006). In 2017, he posthumously reprised the role in Cars 3 thanks to some carefully edited audio out-takes.

Having promised to quit 'when I embarrass myself', Newman kept winning into his 80s, even taking poll position in his last professional race, in 2007, at the Watkins Glen circuit where it had all started four decades earlier. He was posthumously inducted into the SCCA Hall of Fame in 2009, while his exploits were commemorated in Adam Carolla's documentary, Winning: The Racing Life of Paul Newman (2015).

In an interview in 1979, Newman declared, 'Racing is the best way I know to get away from all the rubbish of Hollywood.' Three years later, he found another outlet for his talents, when he and writer A.E. Hotchner launched a range of food products under the label, 'Newman's Own'. Branching out from a salad dressing, the company began making spaghetti sauce, popcorn, salsa, cookies, and wine, with all of the proceeds going to good causes.

Among them was the Hole in the Wall Gang Camp in Ashford, Connecticu, which was launched in 1988 to offer residential summer care for seriously ill children. Further camps have since opened in the United States, Israel, France, and Ireland via the SeriousFun Children's Network. In 2006, Newman co-founded the Safe Water Network and donated $10 million the following year to Kenyon College. At the turn of the millennium, it was announced that Newman had distributed more money, in relation to his own wealth, than any American in the 20th century and, on his death, the Vatican newspaper, L'Osservatore Romano, commended his philanthropy with the tribute, 'Newman was a generous heart, an actor of a dignity and style rare in Hollywood quarters.'

Had he still been alive, President Richard Nixon would not have agreed, as he had Newman at No.19 on his list of enemies. The lifelong Democrat regarded this as one of his proudest achievements, as he campaigned for Civil Rights and against the Vretnam War. His efforts to get Eugene McCarthy and Hubert Humphrey into the White House might have failed, but President Jimmy Carter made him the US delegate at the UN Conference on Nuclear Disarmament in 1978. Along with Woodward, Newman also campaigned for gender equality, gay rights, and climate awareness. But he decided against running for public office himself, as he feared that people would vote for or against him because of his fame and not because of his policies.

It's In the Way That You Use It

'I think that my sense of humour is the only thing that keeps me sane,' Newman told Newsweek in 1994. He had a reputation as a practical joker, once sawing George Roy Hill's desk in half and depositing a compacted Porsche in Robert Redford's hallway. When Robert Altman filled Newman's dressing-room with popcorn, he retaliated by having the director's favourite deerskin gloves breaded, deep-fried, and served up for supper.

Not reading reviews also helped keep Newman on an even keel. 'If they're good you get a fat head,' he reasoned, 'and if they're bad you're depressed for three weeks.' He was almost certainly aware, however, of the negative reaction to James Goldstone's When Time Ran Out... (1980), an Irwin Allen-produced disaster movie that had oil rigger Hank Anderson worrying about the volcanic activity on a Pacific island. At 55, he was also aware that there would be a change in the kind of roles he was offered. However, he was adamant that he would rise to the challenged: 'If blue eyes are what it's all about and not the accumulation of my work as a professional actor, I may as well go into gardening.'

Having directed Woodward and Christopher Plummer in a tele-adaptation of The Shadow Box (1980), Michael Cristofer's Pulitzer-winning play about cancer patients, Newman returned in front of the camera as Murphy, a hard-drinking NYPD officer showing rookie Corelli (Ken Wahl) the ropes on a crime-riddled patch in Daniel Petrie's Fort Apache, the Bronx (1981). Several critics complained that Newman lacked the authenticity to play an ordinary beat cop, but they were back onside when he played Miami liquor salesman Michael Colin Gallagher, whose life is turned upside down by a newspaper story linking him to the murder of a dockyard union official in Sydney Pollack's Absence of Malice (1981). Newman received another Oscar nomination for his work, although he was more concerned with settling a score with The New York Post that had barred him from its pages after he had complained about an inaccurate photo caption.

Newman was in the running for an Academy Award again for his uncompromising performance as alcoholic lawyer Frank Galvin, who takes on a medical malpractice case with little hope of winning in Sidney Lumet's The Verdict (1982). Showing his age and hinting at his flaws, Newman was excited by the avenues the role opened for him.'It was such a relief,' he later said, 'to let it all hang out in the movie, blemishes and all.'

In November 1978, Newman had lost son Scott to a drugs overdose. Accepting that he had not been the best father, he sought to explore his emotions in Harry and Son (1984), in which widowed Florida construction worker Harry Keach butts heads with his son Howard (Robby Benson) over his failure to hold down a regular job while striving to become a writer. Ironically providing Newman with his only screenplay credit, this sobering drama also marked the only time that he directed himself ('Never again - you can't do both.'). But, while the reviews accepted his need to grieve, they found little to admire in the most personal picture of Newman's entire career.

As if sensing as though the 61 year-old needed a pick-me-up, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences presented Newman with an honorary Oscar, 'in recognition of his many memorable and compelling screen performances and for his personal integrity and dedication to his craft'. Accepting via satellite from Chicago, Newman discussed being on a learning curve when it came to acting and feeling emboldened 'to risk and maybe surprise myself a little bit in the hope that my best work is down the pike in front of me and not in back of me'.

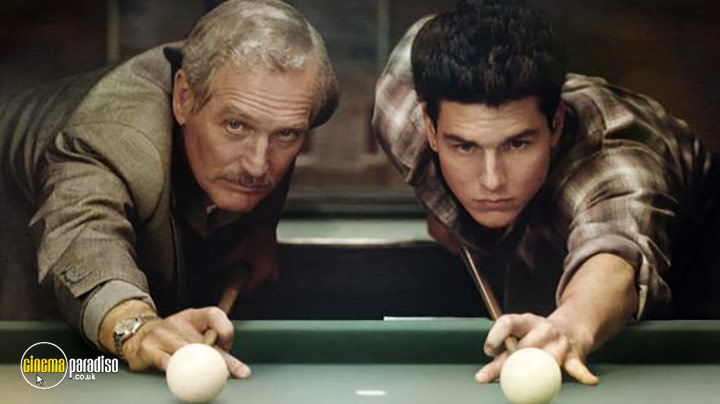

Fulfilling his own prophecy, Newman won the Oscar for Best Actor for reprising the role of 'Fast Eddie' Felson in Martin Scorsese's The Color of Money (1986). Tom Cruise proved such a fine foil as pool hustler Vincent Lauria that some critics felt he stole the picture. But, while there was a sense that this was AMPAS rewarding a career rather than a performance, few begrudged Newman his moment of triumph. Not that he attended the ceremony, as he was convinced he wouldn't win. Indeed, even when asked how he felt about converting his seventh Best Actor nomination, Newman replied, 'A long time ago winning was pretty important. But it's like chasing a beautiful girl. You hang in there for years; then she finally relents and you say "I'm too tired."'

He didn't act in another film for three years, although he was far from idle. He directed Woodward and John Malkovich in a 1987 adaptation of Tennessee Williams's The Glass Menagerie that was selected for the main competition at Cannes. Newman also sued Universal Pictures for the $1 million he claimed he was owed for the video releases of Winning, Sometimes a Great Notion, The Sting, and Slap Shot. After three years, the case was dismissed by the Supreme Court in 1988. But Newman felt he had taken a stand on behalf of his fellow artists against an industry that was seeking to keep home entertainment profits for itself.

Idol With Feet of Clay

Returning to acting after three years, Newman fell foul of critics who had been lying in wait for the Oscar winner. Although he rarely did period pictures, he was enticed into playing General Leslie R. Groves in Roland Joffé's Shadow Makers (aka Fat Man and Little Boy, 1989), an account of the Manhattan Project that co-starred Dwight Schultz as J. Robert Oppenheimer. Matt Damon and Cillian Murphy took the roles in Christopher Nolan's Oppenheimer (2023).

The reviews were equally underwhelming for Ron Shelton's Blaze (1989), which cast Newman as Earl Long, the Louisiana governor whose relationship with stripper Blaze Starr (Lolita Davidovich) caused a scandal in the 1950s. But not even the combinaton of Woodward and Newman with James Ivory, Ismail Merchant, and Ruth Prawer Jhabvala found favour, even though Mr & Mrs Bridge (1990) made a perfectly decent job of adapting two Evan S. Connell novels about a 1930s Kansas City lawyer and his wife trying to curtail the rebellious instincts of their three children.

Four years elapsed (during which time the Academy presented him with the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award) before Newman graced the screen again, as Sidney J. Mussburger, the 1950s business executive in Joel and Ethan Coen's The Hudsucker Proxy, who promotes rookie Norville Barnes (Tim Robbins) to high office at Hudsucker Industries as part of a stock scam. Newman revels in his villainy, but this was another instance of him collaborating with front-rank film-makers on a second-rate story. But any fears that Newman was past his best were allayed by his performance in Robert Benton's Nobody's Fool (both 1994), which earned him another Oscar nomination and the Silver Bear at the Berlin Film Festival. Drawn from a novel by Richard Russo, the story follows Donald J. Sullivan, as he takes a break from jousting with construction boss Carl Roebuck (Bruce Willis) to rebuild bridges with his estranged son (Dylan Walsh). The highlights, though, revolve around Newman's rapport with landlady Jessica Tandy and grandson Alexander Goodwin.

Beside appearances in documentaries like John Huston: The Man, the Movies, the Maverick (1988), Why Havel? (1991), and Baseball (1994), Newman was reluctant to face the camera during this period, as he devoted himself to his myriad other activities, including the Scott Newman Centre for drug abuse prevention. When he did return, as Harry Ross in Robert Benton's Twilight (1998), the critics were unconvinced, despite his grizzled display as a dishevelled shamus who finds himself being duped into dark deeds by ageing movie stars Jack and Catherine Ames (Gene Hackman and Susan Sarandon).

A pairing with Kevin Costner in Luis Mandoki's adaptation of Nicholas Sparks's Message in a Bottle (1999) proved no more successful, as Dodge Blake was rather marginalised by the romantic plot involving shipbuilder son, Garrett, and journalist Theresa Osborne (Robin Wright). Newman had more to do as slippery career criminal Harry Manning enlisting nurse Carol Ann McKay (Linda Fiorentino) in an elaborate heist in Marek Kanievska's Where the Money Is (2000). Both stars deserved better, with Fiorentino disappearing from cinema after briefly burning brightly. Newman got a more suitable send off, however, as ruthless 1930s gangster John Rooney in Sam Mendes's take on Max Allan Collins and Richard Piers Rayner's DC Comics classic, Road to Perdition (2002). Tom Hanks co-stars as the father of the young boy (Tyler Hoechlin) who witnesses a hit by Rooney's henchman, Harlen Maguire (Jude Law), while Daniel Craig featured as the Rock Island Irishman's worthless son. But it was Newman who scooped the Best Supporting Oscar nomination, as he decided to call time on his screen acting career.

In 2001. he guested in 'The Blunder Years', which was Episode 5 of Series 13 of The Simpsons (1989-) and he would contribute narration and/or voicework to Magnificent Desolation: Walking on the Moon (2005), Mater and the Ghostlight (2006), Dale (2007), and Meerkats: The Movie (2008). But he left the stage in style, as the 2003 Broadway revival of Our Town earned Newman a Tony Award and an Emmy nomination after the play was shown on PBS. His final small-screen outing was also garlanded, as his performance as the dissolute Miles Roby in the Fred Schepisi mini-series based on Richard Russo's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, Empire Falls (2005), brought Newman a Golden Globe and a Primetime Emmy.

Such was Newman's commitment to his marriage that he didn't speak to his mother for 15 years after she accused Joanne Woodward of adultery in 1959. When asked about fidelity, Newman always liked to say (somewhat chauvinistically), 'Why go out for a hamburger when you have steak at home?' He claimed the relationship was rooted in 'some combination of lust and respect and patience. And determination.' But Woodward had her own ideas about the secret to their marriage: 'He's very good looking and very sexy and all of those things, but all of that goes out the window and what is finally left is, if you can make somebody laugh...And he sure does keep me laughing.'

Biographer Shawn Levy alleged that Newman had an 18-month fling in the late 1960s with Nancy Bacon, an actress who had appeared n such lowbrow flicks as Sex Kittens Go to College and The Private Lives of Adam and Eve (both 1960). Bacon, who went on to become a famous gossip columnist, confirmed the affair in her autobiography, Legends and Lipstick: My Scandalous Stories of Hollywood's Golden Era. Woodward, however, was more concerned by her husband's drinking, which she called 'the anguish of our lives'. A functioning alcoholic, like his father, Newman gave up hard liquor in 1971, but he continued to get through a case of beer a day until relatively late in his life.

He discussed his intake with Stewart Stern, whom he had hired to conduct a series of interview with himself, family members, and co-workers with the aim of publishing a memoir. However, the tapes were lost in a fire and the transcripts only came to light in the 2010s, which resulted in the publication of The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man in 2022 and the release of Ethan Hawke's mini-series, The Last Movie Stars (2024), which featured the voices of George Clooney as Newman and Laura Linney as Woodward. Both book and series contain some harsh truths. But, as fabled critic Pauline Kael once averred, 'Nobody should ever be asked not to like Paul Newman.'

Despite having been diagnosed with lung cancer (after having smoked heavily until 1986), Newman was scheduled to make his stage directing debut with John Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men at the Westport Country Playhouse. However, he was forced to step down on 23 May and passed away on 26 September 2008, at the age of 83. For all the acclaim and success, he confessed that he had 'never enjoyed acting, never enjoyed going out there and doing it' and had often felt like

'a shell that's photographed onscreen, chased by the fans and garnering all the glory. While whoever is really inside me, the core, stays unexplored, uncomfortable and unknown.'

The self-doubt stayed with Newman to the end, as he claimed, 'I never regarded my performances as real successes; they were just something that was done, nothing more important than someone working hard and getting an A in political science.' In keeping with his legion of fans around the world, we at Cinema Paradiso humbly beg to differ.

-

Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956)

1h 49min1h 49min

1h 49min1h 49minRocky Graziano: 'Well, that's what makes me feel important. I mean, you gotta be there. You got to hear them crowds screamin'. They're screamin' my name. And they're screamin' for me to kill off the other guy. They grab at me when I go up the aisle. That's what makes me feel important.'

- Director:

- Robert Wise

- Cast:

- Paul Newman, Pier Angeli, Everett Sloane

- Genre:

- Drama, Sports & Sport Films, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

The Long Hot Summer (1958)

1h 52min1h 52min

1h 52min1h 52minBen Quick: 'I can see my white shirt and my black tie and my Sunday manners didn't fool you for a minute. Well, that's right, ma'am, I'm a menace to the countryside. All a man's gotta do is just look at me sideways and his house goes up in fire. And here I am, living right here in the middle of your peaceable little town, right in your back yard, you might say. Guess that ought to keep you awake at night.'

- Director:

- Martin Ritt

- Cast:

- Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward, Anthony Franciosa

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

The Hustler (1961)

Play trailer2h 9minPlay trailer2h 9min

Play trailer2h 9minPlay trailer2h 9min'Fast Eddie' Felson: 'You know, I got a hunch, fat man. I got a hunch it's me from here on in. One ball, corner pocket. I mean, that ever happen to you? You know, all of a sudden you feel like you can't miss? 'Cause I dreamed about this game, fat man. I dreamed about this game every night on the road. Five ball. You know, this is my table, man. I own it.'

- Director:

- Robert Rossen

- Cast:

- Paul Newman, Jackie Gleason, Piper Laurie

- Genre:

- Drama, Sports & Sport Films

- Formats:

-

-

Hud (1963)

1h 47min1h 47min

1h 47min1h 47minHud Bannon: 'This country is run on epidemics, where you been? Price fixing, crooked TV shows, inflated expense accounts. How many honest men you know? Why you separate the saints from the sinners, you're lucky to wind up with Abraham Lincoln. Now I want out of this spread what I put into it, and I say let us dip our bread into some of that gravy while it is still hot.'

- Director:

- Martin Ritt

- Cast:

- Paul Newman, Melvyn Douglas, Patricia Neal

- Genre:

- Classics, Action & Adventure, Drama

- Formats:

-

-

Cool Hand Luke (1967)

Play trailer2h 1minPlay trailer2h 1min

Play trailer2h 1minPlay trailer2h 1minLucas Jackson: 'Anybody here? Hey, Old Man. You home tonight? Can You spare a minute. It's about time we had a little talk. I know I'm a pretty evil fellow... killed people in the war and got drunk... and chewed up municipal property and the like. I know I got no call to ask for much... but even so, You've got to admit You ain't dealt me no cards in a long time. It's beginning to look like You got things fixed so I can't never win out. Inside, outside, all of them... rules and regulations and bosses. You made me like I am. Now just where am I supposed to fit in? Old Man, I gotta tell You. I started out pretty strong and fast. But it's beginning to get to me. When does it end? What do You got in mind for me? What do I do now? Right. All right.'

- Director:

- Stuart Rosenberg

- Cast:

- Paul Newman, George Kennedy, Strother Martin

- Genre:

- Drama

- Formats:

-

-

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969)

Play trailer1h 45minPlay trailer1h 45min

Play trailer1h 45minPlay trailer1h 45minButch Cassidy: 'Don't ever hit your mother with a shovel. It will leave a dull impression on her mind.'

- Director:

- George Roy Hill

- Cast:

- Paul Newman, Robert Redford, Katharine Ross

- Genre:

- Classics, Drama, Action & Adventure

- Formats:

-

-

The Verdict (1982)

Play trailer2h 3minPlay trailer2h 3min

Play trailer2h 3minPlay trailer2h 3minFrank Galvin: You know, so much of the time we're just lost. We say, "Please, God, tell us what is right; tell us what is true." And there is no justice: the rich win, the poor are powerless. We become tired of hearing people lie. And after a time, we become dead...a little dead. We think of ourselves as victims...and we become victims. We become...we become weak. We doubt ourselves, we doubt our beliefs. We doubt our institutions. And we doubt the law. But today you are the law. You ARE the law. Not some book...not the lawyers...not the, a marble statue...or the trappings of the court. See those are just symbols of our desire to be just. They are...they are, in fact, a prayer: a fervent and a frightened prayer. In my religion, they say, "Act as if ye had faith...and faith will be given to you." IF...if we are to have faith in justice, we need only to believe in ourselves. And ACT with justice. See, I believe there is justice in our hearts.'

- Director:

- Sidney Lumet

- Cast:

- Paul Newman, Charlotte Rampling, Jack Warden

- Genre:

- Drama

- Formats:

-

-

Mr and Mrs Bridge (1990)

1h 55min1h 55min

1h 55min1h 55minWalter Bridge: 'Some things never change. Love, respect, human decency. It doesn't change. Your Mother and I have those things.'

- Director:

- James Ivory

- Cast:

- Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward, Saundra McClain

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

Nobody's Fool (1994)

1h 45min1h 45minSully Sullivan: 'A condemned man has a right to a last request doesn't he? I got my truck out back, whaddya say we get in the back, get naked and see where it goes from there?'

- Director:

- Robert Benton

- Cast:

- Paul Newman, Bruce Willis, Jessica Tandy

- Genre:

- Comedy

- Formats:

-

-

Road to Perdition (2002)

1h 52min1h 52min

1h 52min1h 52minJohn Rooney: 'There are only murderers in this room! Michael! Open your eyes! This is the life we chose, the life we lead. And there is only one guarantee: none of us will see heaven.'

- Director:

- Sam Mendes

- Cast:

- Tom Hanks, Tyler Hoechlin, Rob Maxey

- Genre:

- Action & Adventure, Thrillers, Drama

- Formats:

-