It's been quite a year for Italy. Not content with winning the Eurovision Song Contest, the country also triumphed at the delayed Euro 2020 tournament, while its male athletes brought home gold in the 100m and 4x100m sprints at the Tokyo Olympics. Now, the focus falls on the record-breaking Venice Film Festival, which, as Cinema Paradiso discovers, is the oldest event of its kind in the world.

Running between 1-11 September, the 78th Venice Film Festival sees the return of the crowds to the Lido after the festivities were scaled back in 2020 because of the pandemic. South Korean Oscar winner Bong Joon-ho leads the jury that will decide the fate of the Golden Lion. But film fans will also be keeping an eye on the major Hollywood releases, as Venice has become something of a bellwether for Oscar success, as Alfonso Cuarón's Gravity (2013) and Roma (2018), Alejandro González Iñárritu's Birdman, or The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance (2014), Tom McCarthy's Spotlight (2015), Damien Chazelle's La La Land (2016), Guillermo Del Toro's The Shape of Water (2017), Yorgos Lanthimos's The Favourite (2018), Todd Phillips's Joker (2019) and Chloé Zhao's Nomadland (2020) all received a boost by being launched at the festival.

From Dubious Origins

Cinema was in its fourth decade before anyone came up with the idea of holding an international showcase for the latest releases. Artists had been showing their paintings as the famous Salon in Paris since 1667, while Venice had been hosting its Biennale since April 1895, when pioneers like the Lumière and Skladanowsky brothers had been trying to project the moving images that Thomas Alva Edison had been exhibiting in his Kinetoscope peepshow viewers for over a year.

The inauguration of the Academy Awards in 1927 had shown that film fans liked the idea of rewarding the best pictures and performances. So, Giuseppe Volpi, Luciano De Feo and Antonio Maraini persuaded the organisers of the Biennale to add a film strand to its programme in 1932. Volpi had been Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini's finance minister and there's no doubt that the Esposizione d'Arte Cinematografica had nationalistic intentions, as the Italian box office at the time was dominated by American imports.

Indeed, the first feature shown at Venice was Rouben Mamoulian's Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, which was screened on the terrace of the Lido's Excelsior Palace Hotel on 6 August 1932. In all, nine nations participated in the festival, which awarded its first prizes on the basis of an audience ballot. Fredric March was voted Best Actor for his dual performance in Robert Louis Stevenson's chiller, while Helen Hayes was named Best Actress for Edgar Selwyn's The Sin of Madelon Claudet. This also won the 'Most Moving Film' award, while Dr Jekyll took the 'Most Original' gong and René Clair's À Nous la Liberté was declared the festival's 'Funniest Film' and its best overall.

Intriguingly, given the growing political tensions on the continent, Nikolai Ekk bagged Best Director for the Soviet Union with Road to Life. Something of a film buff, Mussolini was delighted that 25,000 patrons had paid to see films like Alexander Dovzhenko's Earth (1930). James Whale's Frankenstein (1931), Edmund Goulding's Grand Hotel and Mario Camerini's What Scoundrels Men Are! (1932), a forerunner of neo-realism that was filmed on location in Milan with future director Vittorio De Sica as its star.

Such was his determination to exploit the festival's success that Il Duce introduced the Mussolini Cups for the Best Italian and Best Foreign films. None of the winners of the first award are available on disc, although Augusto Genina's The White Squadron (1936), Carmine Gallone's Scipio l'africano (1937) and Goffredo Alessandrini's Luciano Serra, Pilot (1938) all extolled Italian military virtues and reflected the growing tensions of the time. As did the fact that the Foreign Film category was dominated by Third Reich titles after Leni Riefenstahl's Olympia (1938). But Cinema Paradiso users can enjoy such prize winners as Robert J. Flaherty's Man of Aran (1934) and Clarence Brown's Anna Karenina (1935), as well as Jacques Feyder's La Kermesse Héroïque (1935) and Robert J. Flaherty and Zoltan Korda's Elephant Boy (1937), which took the award for Best Director.

The festival began to take shape under director Ottavio Croze, who was a driving force behind architect Luigi Quagliata's Palazzo del Cinema, which opened in 1938. He also curated the first retrospective, which celebrated French cinema between 1895-1933, and boosted Venice's reputation for attracting glamorous stars, when Marlene Dietrich graced the Lido in 1938.

This period also saw the introduction of the Volpi Cup for the best acting performances, which replaced the Great Gold Medal of the National Fascist Association for Entertainment for the Best Actor and Actress. Despite the success of such big names as Wallace Beery, Paul Muni, Bette Davis, Emil Jannings and Norma Shearer, frustratingly few of the early winners can be seen on disc in this country. However, Cinema Paradiso can present Katharine Hepburn as Jo March in George Cukor's Little Women (1933) and Leslie Howard as Professor Henry Higgins in Anthony Asquith's Pygmalion (1938).

A Golden End to a Decade of Infamy

The outbreak of war in 1939 led to the abandonment of the inaugural Cannes Film Festival, but the Cinema San Marco continued to welcome film-makers from occupied and neutral countries, as well as Italy's Axis allies. Indeed, from 1940-42, the event was renamed the Italian-German Film Festival, with special awards being presented to Nazi propaganda pieces like Gustav Uckicky's Heimkehr (1941). Following the fall of Mussolini in 1943, however, the festival was postponed until the cessation of hostilities, when it moved to its now customary September slot on its 1946 resumption.

Under festival director Elio Zorzi, Jean Renoir's The Southerner (1945) took the Best Feature Prize. This was renamed the Grand International Prize of Venice for its presentation to Czech Karel Steklý's The Strike (1947) and Laurence Olivier's Hamlet (1948), which became the first film to win Venice and the Oscar for Best Picture. The following year saw the first Golden Lion of St Mark presented to Henri-Georges Clouzot's Manon (1949) and this has remained the festival's grand prix ever since.

The splendour of the Doge's Palace provided the back drop for the 1947 edition, which saw the acting awards go to Pierre Fresnay (Monsieur Vincent) and Anna Magnani (Angelina). Nineteen year-old Jean Simmons became the first British actress to win at Venice for her performance as Ophelia in Hamlet, while Ernst Deutsch took the Best Actor honours for G.W. Pabst's The Trial. But the festival was back in the Palazzo del Cinema in time for Hollywood to end the decade with its first sweep of the acting prizes, as Joseph Cotten and Olivia De Havilland were rewarded for their respective turns as Eben Adams in William Dieterle's Portrait of Jennie (1948) and as Virginia Stuart Cunningham in Anatole Litvak's The Snake Pit (1949).

Welcoming World Cinema

During the 1950s, the Venice Film Festival reached out beyond Europe and the United States to welcome talents from Asia and Latin America who would go on to have a major impact on world cinema. Artistic directors Antonio Petrucci (1949-53), Ottavio Croze (1954-55) and Floris Ammannati (1956-59) might appear to have overlooked the neo-realist revolution that was taking place on their own doorstep, but it's likely they were under pressure from the Christian Democrat government helping to fund their event, which claimed that unvarnished snapshots of everyday life like Luchino Visconti's La terra trema and Vittorio De Sica's Bicycle Thieves (both 1948) damaged Italy's reputation abroad.

Nothing seems to confirm this brief more conclusively than the scandal that broke around the 1954 Golden Lion being presented to Renato Castellani's adaptation of William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet rather than Luchino Visconti's Senso or Federico Fellini's La strada. The previous year, the jury had decided not to announce a Best Film, as it had proved impossible to reach a consensus. A similar impasse occurred in 1956 over Juan Antonio Bardem's Calle Major and Kon Ichikawa's The Burmese Harp.

There was no such dispute, however, over the awarding of the Golden Lion to André Cayatte's Justice Is Done in 1950 or René Clément's Forbidden Games two years later. Indeed, France had an excellent decade, with Jean Gabin winning Best Actor for The Night Is My Kingdom in 1951 and for his performances in Marcel Carné's L'Air de Paris and Jacques Becker's exceptional film noir, Touchez pas au grisbi (both 1954). Compatriots Henri Vibert (Le Bon Dieu sans confession, 1953) and Bourvil (Four Bags Full, 1956) also struck gold. By contrast, Madeleine Robinson was the only French actress to triumph in the 1950s, for her superbly controlled performance as wronged wife Thérèse Marcoux in Claude Chabrol's À Double Tour (aka Web of Passion, 1959).

This was the first film by a nouvelle vague director to take a prize at Venice. But the 1950s was a decade of cinematic transformation, not least because of the emergence of such enduringly influential directors as Akira Kurosawa and Satyajit Ray, who respectively won the Golden Lion with Rashomon in 1951 and Aparajito (1959), which was the central part of a Parallel Cinema trilogy that also contained Pather Panchali (1955) and Apur Sansar (1959). To learn more about these fine film-makers and find out which titles are available to rent on high-quality disc from Cinema Paradiso, see our Instant Expert Guides on both Ray and Kurosawa.

Japan enjoyed a second success, when Hiroshi Inagaki's The Rickshaw Man (1958) took the Golden Lion. Moreover, Kenji Mizoguchi's Ugetsu (1953) and Sansho the Bailiff (1954) received the Silver Lion, as did Kurosawa's Seven Samurai (1954). Several other titles available from Cinema Paradiso picked up this award during the decade, including John Huston's Moulin Rouge, Marcel Carné's Thérèse Raquin, Federico Fellini's I vitelloni (all 1953), Elia Kazan's On the Waterfront (1954), Michelangelo Antonioni's Le amiche and Robert Aldrich's The Big Knife (both 1955).

Completing the Golden Lion line-up for the 1950s are Ordet (1955), Carl Theodor Dreyer's austere, but deeply affecting study of faith and love, and the Italian duo of Mario Monicelli's The Great War (why is this not on disc?) and Roberto Rossellini's General della Rovere (both 1959), which became the second grand prix winner to star Vittorio De Sica. Yet, he was never a favoured contender for the Volpi Cup, as Curd Jürgens (Heroes and Sinners, 1955) turned out to be the decade's only non-Anglo-American winner beside Sam Jaffe in John Huston's The Asphalt Jungle (1950), Fredric March in Laslo Benedek's Death of a Salesman (1951), Kenneth More in Anatole Litvak's The Deep Blue Sea (1955), Anthony Franciosa in Fred Zinnemann's A Hatful of Rain (1957), Alec Guinness in Ronald Neame's The Horse's Mouth (1958) and James Stewart in Otto Preminger's Anatomy of a Murder (1959).

It's a shame some of these excellent performances are missing from disc in this country, as is the case with some of the more cosmopolitan selections for the Best Actress prize. But, while we shall have to be patient to see Eleanor Parker (Caged, 1950), Ingrid Bergman (Europa '51, 1952), Lilli Palmer (The Four Poster, 1953), Dzidra Ritenberga (Malva, 1957) and Sophia Loren (The Black Orchid, 1958), Cinema Paradiso users can, however, console themselves with the brilliance of Vivien Leigh as Blanche DuBois in Elia Kazan's adaptation of Tennessee Williams's A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) and Maria Schell as Gervaise Macquart Coupeau in René Clément's interpretation of Émile Zola's Gervaise (1956).

Swinging Off Its Axis

Italy experienced a period of social, economic, political and cultural upheaval during the 1960s, which were known locally as 'the Years of Lead'. Under the directorship of Emilio Lonero (1960-62) and Luigi Chiarini (1963-68), the Venice Film Festival sought to reflect wider society and the impact of the new waves that were breaking around the film world. Indeed, Chiarini strove to resist the pressure imposed by politicians and studio executives to make Venice stand out from the increasing number of festivals around the world.

Although second-time winner André Cayatte's Le Passage du Rhin (1960) seemed a rather conventional Golden Lion choice, compatriot Alain Resnais's Last Year At Marienbad (1961) brought the nouvelle vague to the Lido. Its teasing narrative and striking visual formality found echo in two of the decade's other winners, Luis Buñuel's Belle de jour (1967) and Alexander Kluge's Artists of the Big-Top: Disorientated (1968), more of which anon.

With the exception of Andrei Tarkovsky's Ivan's Childhood (1962), however, the period was dominated by homegrown releases, including Valerio Zurlini's Family Diary, which shared the top prize with Tarkovsky's harrowing war drama.

Francesco Rosi captured the mood of a country in crisis with Hands Over the City (1963), in which Rod Steiger excels as a corrupt property developer, while Monica Vitti and Richard Harris are equally impressive in another state of the nation study, Michelangelo Antonioni's Red Desert (1964), whose use of colour makes it one of the most visually arresting pictures of the 1960s.

Frustratingly, it's not currently possible to see Luchino Visconti's overdue Golden Lion success, Sandra of a Thousand Delights (1965), but Cinema Paradiso users can borrow Gillo Pontecorvo's The Battle of Algiers (1966), which adopted a docudramatic format to examine the Algerian struggle for independence from France. Yet, while the grand prix selections engaged with a rapidly changing world, the Volpi Cup decisions often seemed safe by comparison, particularly in 1960, when the awards went to John Mills for Ronald Neame's Tunes of Glory and Shirley MacLaine for Billy Wilder's The Apartment.

Either side of wins by Burt Lancaster for John Frankenheimer's Birdman of Alcatraz (1962), Tom Finney for Tony Richardson's Tom Jones (1963) and Tom Courtenay for Joseph Losey's King and Country (1964), Toshiro Mifune was commended for his contrasting performances in a pair of Akira Kurosawa features: Yojimbo (1961) and Red Beard (1965). The former, of course, would be a major influence on Sergio Leone's Spaghetti Western, A Fistful of Dollars (1964), and it's intriguing to note the cross-pollinating effect that events like Venice have on commercial and arthouse cinema alike.

But not every prize winner becomes a timeless classic and Almost a Man (1966) and Jutro (1967) have been little seen since earning the Volpi laurels for Frenchman Jacques Perrin and Yugoslav Ljubiša Samardžic. Access has also been limited to such Best Actress titles as Thou Shalt Not Kill (Suzanne Flon, 1961), Thérèse Desqueyroux (Emmanuelle Riva, 1962), To Love (Harriet Anderson, 1964), Three Rooms in Manhattan (Annie Girardot, 1965), The First Teacher (Natalya Arinbasarova, 1966) and Dutchman (Shirley Knight, 1967). Fortunately, it is possible to see Delphine Seyrig's measured turn as the troubled antique dealer in Alain Resnais's Muriel (1963) and both 1968 winners, John Marley's tortured husband in John Cassavetes's Faces and Laura Betti's miracle-performing maid in Pier Paolo Pasolini's Theorem (1968).

With its scathing dissection of bourgeois mores, the latter caused something of a scandal. But it was Artists of the Big-Top: Disorientated (an early example of Das Neue Kino) that brought down Venice's house of cards, as it was considered so radically experimental that it was deemed to have breached the Biennale's rules on subject matter and the depiction of the existing political climate. As a result, the festival looked very different in the 1970s.

Where Have All the Lions Gone?

It's safe to say that the 1970s were a bleak period for the Venice Film Festival. One has to sympathise with directors Ernesto G. Laura, Gian Luigi Rondi and Giacomo Gambetti, as the decision to withdraw all prizes and make the event a non-competitive affair left it looking rather lightweight and listless.

A Golden Lion for lifetime achievement had been inaugurated in 1969, with Luis Buñuel being the first recipient. The following year saw the honour go to Orson Welles, while Ingmar Bergman, Marcel Carné and John Ford shared the accolade in 1971. However, following the presentations to Charlie Chaplin, Billy Wilder and Soviet cinematographer Anatoli Golovnya in 1972, even this award was shelved for the remainder of the decade.

Venice was in danger of becoming a sideshow, as parallel and alternative events like Giornate del cinema italiano were held on the Lido. Gambetti sought to win back audiences with retrospectives and themed sidebars, such as the 1977 focus on Eastern Europe. His efforts proved in vain, however, as the festival was cancelled altogether in 1978 and its very future seemed in doubt.

The Lido Shuffle

Salvation came in the form of Carlo Lizzani, the director of The Hills Run Red, Wake Up and Kill (both 1966), Requiescant (1967) and Last Days of Mussolini (1974), all of which are available to rent on high-quality disc from Cinema Paradiso. During his four-year tenure, Lizzani not only restored the major awards, but he also shook up the way in which the festival was organised. Collaborating with critic Enzo Ungari, Lizzani supplemented the traditional competition films and retrospective strands with an 'Officina' experimenta selection and a 'Mezzogiorno-Mezzanotte' category that was devoted to crowd-pleasing blockbusters.

These reforms were continued by Gian Luigi Rondi (1984-86), who introduced the International Critics' Week, and Guglielmo Biraghi (1987-91), who added the 'Orizzonti', 'Notte' and'"Eventi speciali' slates. Moreover, Biraghi reached out to Africa, the Middle East and South-East Asia to widen the festival's remit.

Gradually, these changes began to influence the films chosen for the Golden Lion. Yet several familiar names took the prize during the 1980s, after Louis Malle's Atlantic City and John Cassavetes's Gloria had shared the award at the start of the decade. Margarethe von Trotta became the first woman to win the top prize, with The German Sisters (1981), which was followed by another German New Wave title, Wim Wenders's The State of Things (1982). although several jury members wanted to give the award to Querelle, the last film by the recently deceased Reiner Werner Fassbinder. His mentor, Jean-Luc Godard struck gold the next year with First Name: Carmen (1983), which is currently as unavailable, as is Krzysztof Zanussi's A Year of the Quiet Sun (1984).

The inimitable Agnès Varda landed the award with her uncompromising study of young womanhood, Vagabond (1985), which contrasted with the perspective presented by her great friend Éric Rohmer in The Green Ray (1986), which was the fifth entry in the 'Comedies and Proverbs' series that is examined in Cinema Paradiso's Instant Expert Guide to Éric Rohmer. And France completed a hat-trick when Louis Malle won his second Golden Lion of the decade with the autobiographical wartime drama, Au revoir les enfants (1987).

The host nation returned to the podium with Ermanno Olmi's adaptation of Joseph Roth's novella, The Legend of the Holy Drinker (1988), which features a standout performance by Rutger Hauer. More significantly, however, Taiwan's Hou Hsiao-hsien took the prize with A City of Sadness (1989), a harrowing account of the 'White Terror' that followed the Communist takeover of Mainland China in the late 1940s.

Unlike Cannes and Berlin, Venice had long fought shy of having a Best Director award. Down the years, the Silver Bear has been presented for Best First Films like Emir Kusturica's Do You Remember Dolly Bell? (1985), as well as for occasional Best Director citations like those for James Ivory's Maurice (1987) and Theo Angelopoulos's Landscape in the Mist (1988). However, the award went into abeyance for 18 years after Martin Scorsese won for GoodFellas (1990).

In 1983, the Volpi Cup seemed about to pass into history when it was decided to give the winners of the Best Actor and Best Actress categories a rectangular plaque. However, the traditional award earned a reprieve in 1988, which would have been no compensation to the male ensemble of Robert Altman's Streamers (1983), Naseeruddin Shah (Paar, 1984), Gérard Depardieu (Police, 1985), Carlo Delle Piane (Christmas Present) or Hugh Grant and James Wilby, who shared the Best Actor prize for Maurice. The same was also true for Darling Légitimus (Sugar Cane Alley, 1983), Pascale Ogier (Full Moon in Paris, 1984), Valeria Golino (A Tale of Love, 1986 - after there had been no award the previous year) - and Kang Soo-Yeon (The Surrogate Woman, 1987).

The decade's lucky Volpi actress winners were Isabelle Huppert for Claude Chabrol's Story of Women and Shirley MacLaine for John Schlesinger's Madame Sousatzka (both 1988), as well as Peggy Ashcroft and Geraldine James for Peter Hall's She's Been Away (1989). Indeed, sharing was the order of the day in the actor competition, as Don Ameche and Joe Mantegna took the prize for David Mamet's Things Change (1988) prior to co-stars Marcello Mastroianni and Massimo Troisi celebrating together for Ettore Scola's What Time Is It? (1989).

The Return of a Past Winner

Festival juries like to present a unified face, but Venice has had its share of controversies. In 1990, novelist Gore Vidal ensured that Tom Stoppard's adaptation of his own stage play, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, pipped New Zealander Jane Campion's more ambitiously cinematic take on Janet Frame's memoir, An Angel At My Table, to the Golden Lion. The following year, Gian Luigi Rondi's jury infuriated admirers of Sixth Generation Chinese maestro Zhang Yimou's Raise the Red Lantern by awarding the top prize to Nikita Mikhalkov's tale of the Mongolian steppe, Urga (both 1991).

Zhang got his Lido moment the following autumn, when The Story of Qiu Ju (1992) took the honours. He would also end the decade on top with Not One Less (1999). However, there was so much going on at the 49th festival that the films rather played second fiddle. Having won the Golden Lion with The Battle of Algiers, Gillo Pontecorvo determined to use his stint as artistic director to make Venice both more glamorous and more appealing to young people.

In addition to staging rock events opposite the Palazzo del Casinò, Pontecorvo also established the 'Finestra sulle immagini' showcase for innovation, oversaw the founding of the World Union of Auteurs, and used the Lifetime Achievement Award to bring some of the biggest names in cinema history to the Palazzo del Cinema. He also encouraged the Hollywood studios to launch their Oscar contenders and box-office hopefuls in order to keep the paparazzi clicking away on the Lido.

The destination of the Golden Lion also became less predictable, with Robert Altman's Short Cuts tying with Krzysztof Kieslowski's Three Colours: Blue (both 1993). There was also no way of separating Macedonian Milco Mancevski's Before the Rain and Taiwan's Tsai Ming-liang's Vive L'Amour (both 1994) before Vietnam's Anh Hung Tran sprang a surprise with Cyclo (1995).

Historians were less impressed with Neil Jordan's Michael Collins (1996) than Roman Polanski's jury, which awarded it the Golden Lion. The Japanese provocateur Takeshi Kitano proved a more popular winner with Hana-bi (1997) before Gianni Amelio secured a ninth home win with The Way We Laughed (1998).

New venues were added under Felice Laudadio (1997-98) and Alberto Barbera (1999-2001), as record numbers flocked to see the stars in town to promote their latest releases or bask in some retrospectival glow. They also welcomed back the Silver Lion for Best Director, which went to Emir Kusturica for Black Cat, White Cat (1998) and China's Zhang Yuan for Seventeen Years (1999).

On the acting side, only dedicated festival-goers will have been able to tick off such Volpi Cup winners as Oleg Borisov (The Only Witness, 1990), Fabrizio Bentivoglio (A Soul Split in Two, 1993), Xia Yu (In the Heat of the Sun, 1994) and Götz George (Deathmaker, 1995). However, Cinema Paradiso users can catch up with the decade's other Best Actor victors, as Gus Van Sant's My Own Private Idaho (River Phoenix, 1991), David Mamet's Glengarry Glen Ross (Jack Lemmon, 1992), Mike Figgis's One Night Stand (Wesley Snipes, 1996), Anthony Drazon's HurlyBurly (Sean Penn, 1998) and Mike Leigh's Topsy-Turvy (Jim Broadbent, 1999) are all available to rent on disc.

Liam Neeson became the first to win Best Actor in a Golden Lion winner, when he prevailed for Michael Collins. However, Gong Li and Juliette Binoche had already become the first performers to achieve this feat in The Story of Qiu Ju and Three Colours: Blue. But all three were upstaged by four year-old Victoire Thivisol, who became the youngest prize winner at any major festival for her performance in Jacques Doillon's Ponette (1996).

Elsewhere, it's not possible to see the winning work of Gloria Münchmeyer (The Moon in the Mirror, 1990), Maria de Medeiros (Two Brothers, My Sister, 1994) and Nathalie Baye (A Pornographic Affair, 1999). But Cinema Paradiso users merely have to click a mouse and wait for their postie to bring them Tilda Swinton in Derek Jarman's Edward II (1991), Isabelle Huppert and Sandrine Bonnaire in Claude Chabrol's La Cérémonie (1995), Robin Tunney in Bob Gosse's Niagara, Niagara (1997) and Catherine Deneuve in Nicole Garcia's Place Vendôme (1999). Now that's what you call service!

Veni, Vidi, Venice

It will come as a surprise to no one who follows film to learn that Venice has yet to have a female artistic director. The millennial era was overseen by Moritz de Hadeln (2002-03) and Marco Müller (2004-11), who added such new strands as 'Cinema del presente', 'Venice Days' and 'Controcampo italiano' to the existing line-up. In 2007, Müller recruited Alexander Kluge to celebrate Venice's 75th anniversary with a major retrospective covering world cinema since 1932. Bernardo Bertolucci was given a special Golden Lion to mark the occasion, which reminded everyone that Cannes didn't have the monopoly on glitz and glamour.

The juries were also instructed to be bold with their selections and Jafar Panahi's The Circle (2000) and Mira Nair's Monsoon Wedding (2001) reinforced the view that Europe and Hollywood now had serious competition from the wider world. Taiwan's Ang Lee confirmed this with a double win for Brokeback Mountain (2005) and Lust, Caution (2007), as did Russian Andrey Zvyagintsev (The Return, 2003), Chinese independent Jia Zhangke (Still Life, 2006) and Israeli Samuel Maoz (Lebanon, 2009). But the integrity of British social realism retained its festival appeal, as Peter Mullan's The Magdalene Sisters (2002) and Mike Leigh's Vera Drake (2004) took the Golden Lion with a pared-down naturalism that Darren Aronofsky also applied to The Wrestler (2008).

Buddhadeb Dasgupta's The Wrestlers (2000) took the first Silver Lion of the noughties, as the competition went out of its way to diversify. Philippe Garrel's Regular Lovers (2005) and Alain Resnais's Private Fears in Public Places (2006) snagged the prize for France, while Brian De Palma proved to be the sole US winner with Redacted (2007). Otherwise, there was an Asian feel to the Best Director roll call, with Iranian Babak Payami's Secret Ballot (2001) being followed by Lee Chang-dong's Oasis (2002), Takeshi Kitano's Zatoichi (2003) and Kim Ki-duk's 3-Iron (2004) in paving the way for Shirin Neshat to become the first Iranian woman to win a major festival directing prize with Women Without Men (2009).

Javier Bardem was the big winner in the Volpi Cup stakes, as he followed Julian Schnabel's Before Night Falls (2000) with a second win for Alejandro Amenábar's The Sea Inside (2004). It was also a good decade for Italy - Luigi Lo Cascio (Light of My Eyes, 2001), Stefano Accorsi (A Journey Called Love, 2002) and Silvio Orlando (Giovanna's Father, 2008) - and the United States - Sean Penn (21 Grams, 2003), David Strathairn (Good Night, and Good Luck, 2005), Ben Affleck (Hollywoodland, 2006) and Brad Pitt (The Assassination of Jesse James By the Coward Robert Ford, 2007) - leaving Brit Colin Firth to snatch the decade's last prize for Tom Ford's A Single Man (2009).

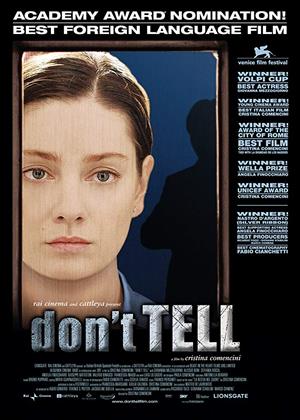

Italy kept pace with Australia and Britain where the Volpi actresses were concerned. Sandra Ceccarelli's win for Light of My Eyes made her and Luigi Lo Cascio the first co-stars to win the acting prizes. But neither this nor Giovanna Mezzogiorno's work in The Beast in the Heart (2005) is currently available on disc. Sadly, the same is true of the performances of Rose Byrne in The Goddess of 1967 (2000), Dominique Blanc in L'Autre (2008) and Kseniya Rappoport in The Double Hour (2009).

But if films are available, Cinema Paradiso invariably has them, as is the case with Julianne Moore in Todd Haynes's Far From Heaven (2002), Katja Riemann in Margarethe von Trotta's Rosenstrasse (2003), Imelda Staunton in Vera Drake, Helen Mirren in Stephen Frears's The Queen (2006), and Cate Blanchett in Todd Haynes's I'm Not There (2007). In winning her award, Mirren became only the second woman after Vivien Leigh to win the Academy Award and the Volpi Cup for the same performance.

One Good Film Lidos to Another

Whether by chance or design, the Golden Lion winner had rarely featured among the front runners at the Oscars. Venice winners were more likely to be worthy arthouse titles like Venezuelan Lorenzo Vigas's gay drama, From Afar (2015), or Filipino Slow Cinema specialist Lav Diaz's The Woman Who Left (2016), neither of which has made it to disc in the UK. At the end of the 2010s, however, the situation changed dramatically, as Guillermo Del Toro's The Shape of Water (2017) and Chloé Zhao's Nomadland (2020) became the first Lido victors to win Best Picture at the Academy Awards since Laurence Olivier's Hamlet.

Alfonso Cuarón's Roma (2018) and Todd Phillips's Joker (2019) also showed prominently at the Oscars, with the former giving Netflix its first Venice triumph. The shift towards the mainstream had been heralded by Sofia Coppola's win for Somewhere (2010) and was continued with the Silver Lions awarded to Paul Thomas Anderson's The Master (2012) and Jacques Audiard's The Sisters Brothers (2018).

Yet the same award showed in the 2010s that festival recognition was no guarantee of commercial success overseas, as only Greek Alexandros Avranas's Miss Violence (2013), Argentinian Pablo Trapero's The Clan (2015), Mexican Amat Escalante's The Untamed (2016) and Xavier Legrand's Custody (2017) made it to disc in the UK, which seems particularly harsh on Russian Andrei Konchalovsky, as he won the award twice.

The decade's other double winner was Swede Roy Andersson, who respectively landed the Golden and Silver Lions for A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence (2014) and About Endlessness (2019). Completing the roll of honour were Aleksander Sokurov's Faust (2011), Kim Ki-duk's Pieta (2012) and Gianfranco Rosi's Sacro GRA (2013), which became the first documentary to win Venice's top prize.

As new director Alberto Barbera went about renovating the festival's grand venues, the event's growing profile made it a must for stars on the promotion trail. In 2013, 70 directors from around the world were invited to make 90-second shorts for the Venice 70 - Future Reloaded anthology, although it didn't travel well. The same also proved true for David Hansen's Jesus VR - The Story of Christ, the first virtual reality feature, which showed in part at Venice in 2016.

As ever, Volpi Cup verdicts caused the occasional eyebrow to raise, especially when Willem Dafoe won for his portrayal of Vincent Van Gogh in Julian Schnabel's critic-dividing At Eternity's Gate (2018). A Venice acting prize doesn't always guarantee a film's box-office success, but Cinema Paradiso has snapped up the cup-winning performances that did make it to disc by the likes of Vincent Gallo (Essential Killing, 2010), Michael Fassbender (Shame, 2011), Joaquin Phoenix and Philip Seymour Hoffman (The Master, 2012), Themis Panou (Miss Violence), Adam Driver (Hungry Hearts, 2014), Fabrice Luchini (Courted, 2015) and Kamel El Basha (The Insult, 2017).

On the actress side, Emma Stone and Olivia Coleman joined the exclusive Volpi-Oscar club with their performances in La La Land (2016) and The Favourite (2018). Valeria Golina also took her second Best Actress prize for Per amor vostro (2015), although the caprices of the distribution and home entertainment systems kept the film from being widely seen. This was also true in the case of Charlotte Rampling's fine display in Hannah (2017), but Cinema Paradiso users can catch up with the winning turns of Ariane Labed (Attenberg, 2010), Deanie Ip (A Simple Life, 2011), Hadas Yaron (Fill the Void, 2012) and Alba Rohrwacher (Hungry Hearts).

It remains to be seen what we shall all be watching from the 2021 slate. But don't be surprised if you hear more about such American titles as Paul Schrader's The Card Counter, Maggie Gyllenhaal's The Lost Daughter and Ana Lily Amirpour's Mona Lisa and the Blood Moon, as well as new works by such major directors as Paolo Sorrentino (The Hand of God), Jane Campion (The Power of the Dog), Pedro Almodóvar (Parallel Mothers) and Pablo Larrain (Spencer).