Half a century ago, Robert Towne wrote a screenplay that is now accepted as one of the best three ever produced in Hollywood. He also contributed to one of the other two. Cinema Paradiso marks the passing at the age of 89 of a master of his art.

Robert Towne once claimed that a good screenplay 'reads like it's describing a movie already made'. It's an apt way to sum up the writing process and its insight justifies Andrew J. Rausch's claim in his book, Fifty Filmmakers: 'There is a strong case to be made that Robert Towne is the most gifted scribe ever to write for film. There can be little doubt that he is one of the finest ever.'

In his seminal text on New Hollywood, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, Peter Biskind declared Towne to have been 'a sweet, gentle, self-effacing man. In a town full of dropouts, where few read books, he was unusually literate. He had a real feel for the fine points of plot, the nuances of dialogue, had the ability to explain and contextualise film in the body of Western drama and literature.'

Producer Gerald Ayres told Biskind that Towne 'had this ability, in every page he wrote and rewrote, to leave a sense of moisture on the page, as if he just breathed on it in some way. There was always something that jostled your sensibilities, that made the reading of the page not just a perception of plot, but the feeling that something accidental and true to the life of a human being had happened there.'

Critic Michael Sragow was equally complimentary about Towne's distinctive skills. 'He knows how to use sly indirection, canny repetition, unexpected counterpoint and a unique poetic vulgarity to stretch a scene or an entire script to its utmost emotional capacity. He's also a lush visual artist with an eye for the kind of images that go to the left and right sides of the brain simultaneously.'

Yet film historian David Thomson declared Towne to be 'a fascinating contradiction: in many ways idealistic, sentimental and very talented; in others a devout compromiser, a delayer, so insecure that he can sometimes seem devious'. Cinema Paradiso goes in search of the man and his movies.

On the Dock of the Bay

Robert Bertram Schwartz was born on 23 November 1934 in Los Angeles. Parents Lou and Helen respectively claimed Romanian and Russian heritage, with one grandmother being a fugitive from an anti-Jewish pogrom and another being a Gypsy fortune-teller. Apparently, the young Robert also 'had a great-grandfather I wasn't allowed to meet. He was over ninety, tall, white-haired, a writer, and a womaniser of sorts, I hear. My mother has since said she regrets not introducing us.'

Shortly after they settled in the fishing port of San Pedro, Lou and Helen welcomed a second son, Roger. They also changed their surname after Lou bought a women's clothing outlet named 'Towne Smart Shop'. As Towne later wrote of his first home: 'It was full of fishermen, merchant marines, cannery workers, dock workers, shipyard workers, soldiers at Fort MacArthur, sailors from everywhere, first-generation Slavs, Italians, Portuguese, Germans, Filipinos, Mexicans, and even a sprinkling of Blacks and Jews. Only if you were five years old could you count on English not being the second language of your peers.'

It was in San Pedro that the seven year-old Towne went to the pictures for the first time, when he ventured into the Warner Bros Theatre on Sixth Street to watch a programme of serials and Howard Hawks's Sergeant York (1941), which would earn Gary Cooper the Oscar for Best Actor. From that moment, Towne was hooked and he started noticing when films were phony. 'I knew it was a flat-out lie,' he later wrote, 'when the movie was set in Los Angeles and the men wore hats and overcoats...I suppose I saw movies as a way of redressing a wrong. I would use one illusion - movies - in order to make another illusion - Los Angeles - real,'

Around this time, Towne started writing his first stories. But Lou had gone up in the world after becoming a property developer and the family moved to a gated community in Rolling Hills in the affluent enclave of Palos Verdes before finally landing in Brentwood. The brothers were educated at the exclusive Chadwick Prep School and Redondo Union High before Robert went off to Pomona College in Claremont, California to study English literature and philosophy. Graduating in 1956, he spent some time in military intelligence and dabbled in real estate before working on a commercial tuna boat. The experience stuck with him, as he told the Writers Guild in 2013: 'I've identified fishing with writing in my mind to the extent that each script is like a trip that you're taking - and you are fishing. Sometimes they both involve an act of faith...Sometimes it's sheer faith alone that sustains you, because you think: "God damn it, nothing - not a bite today. Nothing is happening."'

Corman Get It

While at Pomona, Towne had taken a creative writing class and briefly considered becoming a journalist. He had also befriended aspiring actor Richard Chamberlain and had accompanied him to an acting class given by HUAC blacklistee, Jeff Corey. Cinema Paradiso users can see Corey in action in Roy William Neill's Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943), John Frankenheimer's Seconds (1966), Henry Hathaway's True Grit (1969), and Arthur Penn's Little Big Man (1970), as well as in George Roy Hill's Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) and Richard Lester's Butch and Sundance: The Early Days (1979), in which he played Sheriff Bledsoe.

Also in the class of 1958 were James Coburn, Sally Kellerman, Irvin Kershner, and Jack Nicholson. But, while they developed their acting skills, Towne found that Corey's methods helped him develop as a writer. He later recalled one exercise designed to explore dramatic structure. 'You are given a situation and told that you must talk about everything but the situation to advance the action,' he explained. Take a very banal situation - a guy trying to seduce a girl. He talks about anything but seduction, anything from a rubber duck he had as a child to the food on the table...It's inventive, and it teaches you something about writing.' As he told another interviewer, 'My training as a writer really came from seven years of improvising in that class, and coming to have a feeling for what was effective dramatically, what was effective in terms of dialogue and just what people could and couldn't say to be effective.'

Another classmate was Roger Corman, who had started to make a name for himself as a writer, director, and producer (as we saw in Roger Corman's Poe Cycle ). He offered Towne a role in his forthcoming sci-fi project, Last Woman on Earth (1960). Moreover, he asked him to write the story of a ménage that develops between a married couple and their lawyer friend when a dip off the coast of Puerto Rico saves them from Armageddon. In order to co-star with Betsy Jones-Moreland and Antony Carbone, Towne adopted the pseudonym, Edward Wain, which he used again when Corman had him narrate Creature From the Haunted Sea (1961), in which he also reunited with his earlier co-stars, as Agent XK150 poses as Sparks Moran in order to prevent a gangster from using rumours of an sub-aquatic monster to smuggle some Cuban booty.

When Corman turned down his provocatively topical adventure, I Flew a Spy Plane Over Russia (1962), Towne decided to spread his wings and sought scripting work in television. 'It was tough making a living writing for Roger,' he later grumbled, 'but at least he gave me a start.' Indeed, Corman hired Towne as assistant director on The Young Racers (1963) before he cut his teeth writing episodes for The Lloyd Bridges Show, Breaking Point (both 1963-64), The Outer Limits (1963-65), and The Man From U.N.C.L.E. (1964-68), with 'The Chameleon' and 'The Dove Affair' from the latter two shows being available to rent from Cinema Paradiso.

Noting how Towne was progressing, Corman brought him back into the fold to adapt Edgar Allan Poe's Tomb of Ligeia (1965), in which the spirit of the first wife of Verden Fell (Vincent Price) targets his new bride, Rowena Trevanion (Elizabeth Shepherd). 'I worked harder on the horror screenplay for him than on anything I think I have ever done,' Towne revealed in 1981. 'And I still like the screenplay. I think it's good.'

Corman was also sufficiently impressed to commission Towne to adapt Nelson and Shirley Wolford's The Southern Blade, a story about a rogue Confederate unit refusing to accept that the Civil War was over. Glenn Ford signed up for what would be his 100th film, with a young Harrison Ford (no relation) down the cast list in taking his first credited role. However, Corman fell out with the Columbia front office and Phil Karlson completed A Time For Killing (aka The Long Road Home, 1967). Towne was so dismayed by the finished film that he had his name removed, with the on-screen credit going to Halsted Welles, who had joined forces with Elmore Leonard in scripting Delmer Daves's 3:10 to Yuma (1957) for Glenn Ford before going on to become a prolific TV writer, with six episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1955-62) to his name.

By chance, Towne's screenplay had come to the attention of Warren Beatty, with whom he happened to share a psychoanalyst. He was too big a star to play second banana to Ford. But he was intrigued by the calibre of Towne's writing and he would remember him when a film he was making with Faye Dunaway ran into a few scripting issues.

The Go-to Guy

Screenwriters Robert Benton and David Newman had been so influenced by the nouvelle vague that they had sought François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard to direct Bonnie and Clyde (1967). They had wound up with Arthur Penn, who had directed Beatty in Mickey One (1965). With Beatty producing the story of Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow, however, he insisted on playing a key role in taking creative decisions. Amidst the endless rows with Penn, Beatty summoned Towne to iron out the wrinkles in the ménage subplot involving Clyde, Bonnie (Faye Dunaway), and C.W. Moss (Michael J. Pollard), as he refused to play a character who could be mistaken for gay.

Towne had always been irritated by films in which characters readily found parking spaces on busy streets and took their change in shops and restaurants without counting it. So, he incorporated such details into the script, while also switching the odd scene around, so that the encounter with undertaker Eugene Grizzard (Gene Wilder) happens before the visit to Bonnie's mother (Mabel Cavitt) in order to emphasise the creeping shadow of death ('You try to live three miles from me and you won't live long, honey.')

Present on set and in the editing suite, Towne was rewarded with the credit 'special consultant' and word spread that he was now Hollywood's leading script doctor. He took the role very seriously. 'You must adopt the first precept of Hippocrates,' he explained, 'which is to do no harm. You try to extend the material, not to impose yourself on it.' Towne also found the process invigorating. 'You learn things from other people,' he told one interviewer. 'All scripts are rewritten. The only question is whether it is rewritten well or badly. On the whole, it's better to have a reputation for fixing things.'

His new métier enabled Towne to keep working, as he struggled with health issues that left him so exhausted that he found it difficult to tackle a whole script. He half-joked that he was suffering from 'writer's hypochondria'. But, in 1972, doctors finally determined that his energies were being sapped by a combination of allergies. In The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Years of Hollywood, Sam Wasson suggested that Towne's problems were exacerbated by an addiction to cocaine. According to some sources, he could become violent towards partner Julie Payne, whom he had met in 1968.

During their marriage from 1977-82, Towne became the son-in-law of Hollywood stars John Payne and Anne Shirley. Cinema Paradiso members can see the pair in action in several films (use the searchline for full details). But we must point you in the direction of Payne's performances in Irving Cummings's The Dolly Sisters (1945), George Seaton's Miracle on 34th Street (1947), and Allan Dwan's Slightly Scarlet (1956) and Shirley's displays in John Ford's Steamboat Round the Bend (1935), William Dieterle's The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941), and Edward Dmytryk's Murder, My Sweet (1944).

Paramount Pictures chief, Robert Evans, asked Towne to work his magic on Villa Rides! (1968), when Yul Brynner took exception to Sam Peckinpah's interpretation of a biographical tome by William Douglas Lansford. With Brynner in the title role and Robert Mitchum as a fictional American adventurer, the shoot proved fraught after Buzz Kulik replaced Peckinpah as director. Towne hated the experience and was recorded in John Joseph Brady's The Craft of the Screenwriter (1981) as claiming the production was a 'a textbook on How Not to Make a Movie'.

Having used the name Robert Tubin to play Man in Bar #3 in Tom Hanson's The Zodiac Killer, Towne took his most substantial acting role, Richard the cuckolded teacher, in Jack Nicholson's directorial debut, Drive, He Said (both 1971). The actor co-wrote the screenplay with source novelist Jeremy Lanner, but both Towne and future director Terrence Malick made uncredited contributions.

Producer Gerald Ayres called Towne in to take another pass at the screenplay that debuting director, Bill L. Norton, had penned for Cisco Pike (1971). In his first screen lead, Kris Kristofferson was well cast as the pop star on the skids and Towne built up his relationship with his girlfriend, Sue (Karen Black), as well as introducing corrupt cop, Leo Holland (Gene Hackman), who threatens to bust Pike unless he deals marijuana for him. Towne felt he had created 'a pretty good movie', but so resented Norton's on-set rewrites that he had his name removed from the credits.

The same thing occurred on Richard Fleischer's The New Centurions (1972), which had been adapted by Stirling Silliphant from a bestseller by Joseph Wambaugh. Co-producer Irwin Winkler felt that the scenario didn't make enough of George C. Scott's imposing presence as Andy Kilvinski, the veteran LAPD cop paired with rookie Roy Fehler (Stacy Keach). So, Towne was hired for a fortnight to bump up his part, with scenes like the climactic phone call. He received $200,000 (around $1.5 million in today's money) for his efforts, but asked for his name to be removed from the picture after he saw it.

Towne was much prouder, however, of his involvement with Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather, (1972). The director had worked on the screenplay with source novelist Mario Puzo and was busy shooting when he realised that he didn't have a scene in which the baton passes between Don Vito Corleone (Marlon Brando) and his youngest son, Michael (Al Pacino). Towne set the meeting on the edge of the family garden and starts it with chit-chat about Vito's consumption of red wine and the antics of Michael's young son. But they get down to the business of Vito expressing his fears for his favourite child taking over the family business ('I never wanted this for you') and Michael reassuring his father that he was ready to shoulder the burden.

It's an exchange filled with affection and apprehension and Coppola was so grateful that he drew attention to it in his speech at the Academy Awards: 'And then, giving credit where it's due, I'd like to thank Bob Towne who wrote the very beautiful scene between Marlon and Al Pacino in the garden; that was Bob Towne's scene.' Coppola's gratitude further extended to him hiring Towne to adapt John Fante's The Brotherhood of the Grape for Philip Kaufman to direct for the new Zoetrope company.

Nothing came of the project, although Towne became friends with the reclusive Fante, who described him as 'a very sweet guy, gentle as a kitten and crafty as a wolf'. Towne would return to Fante's canon later in his career. In the meantime, he had started to become frustrated as being the 'relief pitcher who could come in for an inning, not pitch the whole game'. After conquering his demons, Towne was ready to write a full screenplay.

To Hal and Back

Thanks to producer friend Gerald Ayres, Towne's polishing skills had come to the attention of director Hal Ashby. He was about to adapt Darryl Ponicsan's novel, The Last Detail, in which two members of a naval escort, Billy Buddsky and Richard Mulhall, take prisoner Laurence Meadows on a circuitous route from the Virginia Naval Base to the New Hampshire Naval Prison. Towne's old roommate, Jack Nicholson, had been cast as Buddsky and he ensured that Towne was not removed after he dropped 342 f-bombs in the first seven minutes. In his defence, Towne countered, 'This is the way people talk when they're powerless to act; they b*tch.'

The production was held up while Nicholson completed Bob Rafelson's The King of Marvin Gardens (1972) and Columbia got so twitchy about the delay that they considered passing on the project. However, the hiatus allowed Ashby and Ayres to read up on naval procedures and correct the odd slip in Towne's script. It also meant that Otis Young was cast as Mule after Rupert Crosse was diagnosed with terminal cancer and Randy Quaid pipped John Travolta to the role of Larry. Towne had invisaged him as a small fellow and was impressed by the switch: 'There's a real poignancy to this huge guy's helplessness that's great. I thought it was a fantastic choice, and I'd never thought of it.'

Nicholson won Best Actor at Cannes and landed Oscar and BAFTA nominations, along with Quaid. Towne received a nod for Best Adapted Screenplay, only to lose out to William Peter Blatty for William Friedkin's The Exorcist. Some suggested that Towne paid for changing the novel's happy ending, but he defended his choice with the provocative quip, 'Everybody hides behind doing a job, whether it's massacring in My Lai or taking a kid to jail.'

Now commanding $150,000 for adaptations and $300,000 for original screenplays (plus a percentage of the box-office takings), Towne was now an A-list screenwriter. Rather than pursuing a personal project, however, he agreed to redraft some scenes for Warren Beatty's next project, Alan J. Pakula's The Parallax View (1974), a conspiracy thriller that captured the mood of the country in the aftermath of the Watergate controversy and typified the kind of adult drama coming out of New Hollywood. However, a Writers Guild strike delayed the shoot and Towne was so dismayed to receive a request for rewrites that he reportedly sent his large dog to the producer's office with a note that read: 'This is all that I can give.'

Beatty forgave the truculence, as he and Towne had spent the last seven years teasing out a story idea. While Towne was in Dallas for principal photography on Bonnie and Clyde, he had mentioned that he was working on an update of William Wycherley's 1675 Restoration comedy, The Country Wife. Beatty was amused by the notion of a man convincing his friends that he is impotent so that they will trust him with their spouses and told Towne to get writing when he suggested that the plot should revolve around a womanising hairdresser. But, while Towne could tweak the work of other people with ruthless efficiency, self-doubt crept in whenever he was the principal author.

As Robert Evans opined: 'Towne could talk to you about a screenplay he was going to write and tell you every page of it, and it never came out on paper. Never.' Peter Biskind reckoned that Towne had trouble with structuring scenarios, as 'for all his facility with words, he was not a born storyteller'. Scripts of 250 pages were not unusual, as a time when the average length was around 120. Beatty recalled receiving the draft for Shampoo (1975) and lamenting, 'Robert had written a script that was very good in atmosphere, and in dialogue, but very weak in story, and each day the story would go in whatever direction the wind was blowing. He just never wound up with anything.' When Towne failed to come up with the goods, Beatty signed up with Julie Christie to do Robert Altman's McCabe and Mrs Miller (1971), while he waited for a usable script.

Much water passed under both bridges before Hal Ashby joined the project and helped Towne focus his mind. By this time, Watergate had happened, which made setting the action on Election Day 1968 seem all the more bitingly satirical. Christie and Beatty were now an item and they were joined in the cast by Goldie Hawn and Lee Grant, who would win the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress. Towne and Beatty were nominated for their screenplay and took home the awards from the National Society of Film Critics and the Writers Guild.

Moreover, Shampoo trailed only Steven Spielberg's Jaws and Miloš Forman's One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest in the end-of-year box-office charts. As for Towne, his status had never been higher. The doyenne of American critics, Pauline Kael, wrote: 'With his ear for unaffected dialogue, and with a gift for never forcing a point, Towne may be a great new screenwriter in a structured tradition - a flaky classicist.' However, we have to take a step back to examine the other picture on which his newly vaunted reputation rested.

Forget It, Jake

Around the time that Jack Nicholson was starring with Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda in Easy Rider (1969), he had asked former flatmate Robert Towne to write him a crime procedural with a Raymond Chandler feel. While he was mugging up on hard-boiled fiction, Towne saw a photo essay in West, the Sunday supplement of The Los Angeles Times, entitled 'Raymond Chandler's L.A.' This made him realise that 'you could still recapture the L.A. that I vaguely remembered by the judicious selection of locations around the city, many of which I knew'.

Turning down Robert Evans's $175,000 offer to adapt F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby (Francis Ford Coppola eventually did the job for Jack Clayton's 1974 version), Towne asked for $25,000 to develop his gumshoe idea. While working on Drive, He Said, he found further inspiration in a 1946 book by Carey McWilliams. 'While I was there at the University of Oregon, I checked out a book from the library called Southern California Country: Island on the Land. In it was a chapter called "Water, Water, Water", which was a revelation to me. And I thought, "Why not do a picture about a crime that's right out in front of everybody?" Instead of a jewel-encrusted falcon, make it something as prevalent as water faucets and make a conspiracy out of that. And after reading about what they were doing, dumping water and starving the farmers out of their land, I realized the visual and dramatic possibilities were enormous. So that was really the beginning of it.'

The story of Chinatown (1974) was inspired by the career of William Mulholland, the Irish immigrant whose turn-of-the-century aqueduct had enabled Los Angeles to grow into a metropolis that sprawled into the desert. However, Hollis I. Mulwray (Darrell Zwerling), the chief engineer of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, gets bumped off and his murder brings private detective J.J. Gittes (Nicholson) into the orbit of his widow, Evelyn (Faye Dunaway), and her ruthlessly powerful father, Noah Cross (John Huston).

Evans wasn't enthused by the idea, even when Towne reassured him that the film wouldn't be about Chinatown, but would riff on the notion of it being 'a state of mind'. Secluding himself in a bed-and-breakfast cabin on Catalina Island, Towne laboured for nine months on a screenplay that weighed in at 180 pages. When Nicholson suggested that friend Roman Polanski should direct, the Pole recognised the quality of the concept, but insisted on a major rewrite to disentangle the core plot from Towne's tangents. The pair argued bitterly over the text, with Polanski later recalling, 'Bob would fight for every word, for every line of the dialogue as if it was carved in marble.' It's safe to say that he found him a difficult collaborator. 'Bob Towne is a craftsman of exceptional power and talent,' Polanski wrote in his autobiography. 'He's also a very slow writer, delighting in any form of procrastination, turning up late, filling his pipe, checking his answering service, ministering to his dog.' Alluding to another potential reason for his slow progress, someone snarkily dubbed him, 'write-a-line, snort-a-line Towne'.

The biggest bone of contention was the ending. As Polanski had not visited Los Angeles since the murder of pregnant wife Sharon Tate by some members of Charles Manson's Family in 1969, he wanted the conclusion to reflect the ugliness and violence of life in the city. Towne wanted an upbeat denouement, as the action took place in the city of his childhood. However, Polanski prevailed ('If a film-maker tries to avoid upsetting people, that would be immoral.') and Towne conceded that going down 'the tunnel at the end of the light' was the correct decision, right down to the famous last line, spoken by Lieutenant Lou Escobar (Perry Lopez): 'Forget it, Jake. It's Chinatown.'

Towne later said of Polanski, 'Chinatown would have been a disaster without him.' But he also had his misgivings. 'Up to the very last moment,' he confessed, 'I was one of those who thought Chinatown was going to be a disaster.' It proved to be a critical success, however, going on to receive 11 Oscar nominations, including Best Original Screenplay. Towne had won the Golden Globe and the BAFTA. But, on the big night, he ran into Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather Part II, which was also produced by Paramount and had become the studio's front runner during the award season. When the Writers Guild of America voted for its 101 Greatest Screenplays in 2006, however, Chinatown only trailed The Godfather and Michael Curtiz's Casablanca (1942). Eight years later, when presenting Towne with an honorary fine arts doctorate at the American Film Institute, Coppola declared, 'You have in your script for Chinatown provided the de facto blueprint for aspiring screenwriters, a platonic ideal of both structure and style taught as a template around the world.'

Amused by the fact his scenario was pored over by film students, Towne quipped, 'We weren't trying to write a screenplay that was perfectly structured. We were just trying to make it make sense.' He told Vanity Fair, 'What I hit upon just by a kind of monkey-at-a-typewriter trial and error - that somebody can extrapolate a formula from it astonishes me. Maybe there are rules, and maybe I stumbled across them, but I don't even know what "story-sense" is. I had the same hard time [on later work] that I had on Chinatown.'

In creating Gittes, Towne had striven to make him 'a detective who was not a tarnished knight like Philip Marlowe, but kind of a sleazy, charming, dapper guy who would only take [divorce] cases because they made him the most money'. Towne was eager to base a trilogy around him, with the water theme being followed by mysteries concerning those other Californian staples, oil and land. However, Chinatown's $29 million gross meant that nobody was in a hurry to greenlight a sequel and (as we shall see in the next section), during the seven years that followed Shampoo, Towne returned to being a jobbing hack who pepped up the work of others.

Nicholson was keen to reprise the character, though, and Evans set Towne the task of concocting a new story that would also have a sizeable role for Dustin Hoffman. It took Towne eight years to complete the script, which was set in 1948 and saw Gittes return from war service to uncover another land conspiracy involving a man named Jake Berman. Paramount wasn't convinced, however, especially as Towne wanted to direct. So, he Nicholson and Evans formed their own company and agreed to waive up-front fees in order to produce a film that Paramount would distribute in return for a $12 million contribution towards the budget.

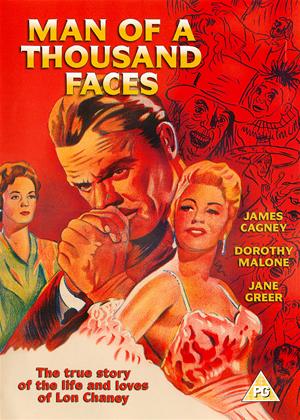

Richard Sylbert designed the sets that were built at Laird International Studios in Culver City, where Kelly McGillis, Cathy Moriarty, Harvey Keitel, Dennis Hopper, Joe Pesci, and Scott Wilson assembled in the spring of 1985, along with veteran director Budd Boetticher, who was to take a rare acting role (use the Cinema Paradiso Searchline to rent the classic Randolph Scott Westerns bearing his name). However, Towne had a problem. As he had been an actor before becoming a studio suit (see Joseph Peveny's Man of a Thousand Faces, 1957), Evans fancied the idea of playing Berman. Despite patient coaching, it became clear that he wasn't up to the task. But things came to a head when Towne started filming make-up tests. As he had recently undergone a cosmetic procedure, Evans refused to have his hair cut into a 1940s style, as it would have revealed his healing scars.

After a lengthy stand-off, Towne told Nicholson that he would have to fire Evans. However, the actor suggested a compromise: 'Let's start shooting and see about Evans later. Give him a chance. If he doesn't cut it then, replace him. His scenes don't come up for four weeks anyway.' When the cast and crew reported for location work in Ventura on 1 May, however, it was evident that all was not well and rumours started to circulate. 'There were telephone talks all day with lawyers and the studio,' one eyewitness recalled, 'and you heard stories that maybe Towne was going to sell the script and maybe John Huston was going to direct. And maybe Roy Scheider was going to play Berman.'

But no Plan B materialised and the production was abandoned without a single frame of film having been exposed by Caleb Deschanel's camera. Desperate to salvage the project, Towne tried to persuade producer Dino De Laurentiis to back him, with Harrison Ford replacing Nicholson as Gittes. But Paramount refused to allow the scenario to be a sequel to Chinatown and Towne was faced with undertaking extensive rewrites in order to avoid a legal suit. As he had agreed to work with Oliver Stone on the screenplay for Hal Ashby's 8 Million Ways to Die (1986), he realised the moment had passed and the picture folded.

Four years later, Towne contented himself with faxing rewrite pages from Bora Bora, as Nicholson directed himself in The Two Jakes (1990). He later told writer Alex Simon, 'In the interest of maintaining my friendships with Jack Nicholson and Robert Evans, I'd rather not go into it, but let's just say The Two Jakes wasn't a pleasant experience for any of us. But, we're all still friends, and that's what matters most.' Nicholson would aver that the pair hadn't exchanged a word in a decade, which put paid to a third feature that was due to have been set in 1968 and turn around the reclusive Howard Hughes. Towne denied any knowledge of Gittes vs Gittes, but he returned to the character in 2019, when director David Fincher approached him to work on a pilot for a Netflix series about the experiences of a young Gittes as a rookie cop in 1920s Chinatown. A month before he died, Towne told Variety that all of the episodes for the show had been scripted. We shall await with bated breath.

Staying Busy

Surprisingly, for someone of Towne's talent, he often found himself scrabbling around for assignments. Daunted by the prospect of taking on solo projects, he readily accepted script doctoring commissions. Many of these were uncredited, but Towne had the satisfaction of being associated with some fine films. Among them was The Yakuza (1974), on which he worked with Paul Schrader.

Leonard Schrader had come up with the idea while teaching in Japan after fleeing the Vietnam draft and the siblings had spent weeks watching Toei crime movies before writing their script. Robert Aldrich wanted to direct with Lee Marvin as the retired detective who goes to Tokyo to find a friend's kidnapped daughter. However, Aldrich thought the screenplay was a mess and replacement Sydney Pollack insisted on Towne lending a hand when he came aboard with a view to starring Robert Redford. Ultimately, it was decided that he was too young and Robert Mitchum took the lead opposite Japanese icon, Ken Takakura. But the film only did modest business before becoming something of a cult favourite.

As a favour to Nicholson and Arthur Penn, Towne took at look at Thomas McGuane's script for the counterculture Western, The Missouri Breaks, which co-starred Marlon Brando. Robert Evans invited Towne to tidy up the fourth draft of William Goldman's screenplay for John Schlesinger's Marathon Man (both 1976), which had the producer raving, 'This is the best thing I've read since The Godfather. It could go all, all the way - if we don't foul it up in the making.'

Sadly, things didn't go quite as well with Michael Anderson's Orca, the Killer Whale (1977), as Richard Harris's drinking and refusal to use stunt doubles made life difficult in the Canadian Arctic for a Jaws-like saga that saw Towne give Luciano Vincenzoni and Sergio Donati's screenplay a little boost. Warren Beatty was the next to come calling, as he and Elaine May sought assistance on Heaven Can Wait (1978), in which Beatty directed himself as an American footballer who discovers that his death is a bureaucratic error. This reworking of Alexander Hall's Here Comes Mr Jordan (1941) had been written for Muhammad Ali, but he was too busy boxing to commit.

In gratitude for his contribution, Beatty recruited Towne for Reds (1981) in order to help May and Peter Feibelman tweak the script that Beatty and playwright Trevor Griffiths had adapted from John Reed's tome, Ten Days That Shook the World. They lost out at the Academy Awards to Colin Welland for Hugh Hudson's Chariots of Fire.

Sport played a key role in a couple of pictures penned by the Towne brothers around this period. Baseball enabled Roger Towne to make his screenwriting debut in adapting Bernard Malamud's The Natural (1984) for Barry Levinson and Robert Redford. However, he would only complete two more big-screen projects in Roger Donaldson's The Recruit (2003) and Margaret Whitton's A Bird of the Air (2011).

The latter is not currently available on disc and neither is Robert Towne's directorial debut, Personal Best (1982), which is a shame, as Mariel Hemingway and Patrice Donnelly impress as the US Olympic athletes who fall in love to the dismay of coach Scott Glenn. Unfortunately, Towne's affairs with each actress led to the collapse of his marriage. Moreover, the difficulties he had in keeping the production on track prompted executive producer David Geffen to opine that Towne was 'over budget, behind schedule, and not in a condition that inspired confidence'. In order to finish the picture, Towne hired Allen Klein (the business manager who had broken up The Beatles) to cut a deal by which he remained at the helm in return for giving up control of his long-gestating film about Tarzan. He later lamented, 'It meant for me I had to accept the death of one child to preserve another.'

Towne had started working on Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes in 1974, when Warners acquired the rights to the novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs. 'It won't be a caricature or a popularisation,' producer Stanley Jaffe had revealed on announcing that Towne had been asked to write the screenplay. 'It will be a serious period action adventure true to the characters and done in terms of contemporary mores.' With this in mind, Towne decided to take a unique approach. 'As I wrote it,' he explaind, 'at least 70 minutes or so would have been silent with apes and a child. The problems of trying to delineate character through movement without much dialogue interested me.'

However, even the most adventurous New Hollywood producer knew that audiences were not going to sit through such a prologue and no one offered to bankroll the project. It was still on the shelf when Towne got into $13 million-worth of difficulties with Personal Best and Hugh Hudson inherited the screenplay, which he promptly spent nine months rewriting with Michael Austin. On seeing their efforts and hearing that Hudson planned on asking make-up guru Rick Baker to create simian suits rather than working with real apes, Towne had his name removed from the credits and replaced by P.H. Vazak. It was only when the script was nominated for an Oscar that it emerged that Towne's Hungarian Komondor sheepdog was named Pannonia's Hira Vazak. Frustratingly, it didn't become the first hound to win an Academy Award, as Peter Shaffer prevailed by adapting his own stage hit for Miloš Forman's Amadeus (both 1984). But Greystoke was the first Tarzan movie to have merited an Oscar nod.

Cruising Along

Crushed by seeing what he considered to be his finest screenplay bowdlerised, Towne sued Warners for $110m. He failed to win and claimed to be so broke that he was having to live in a boarding house. A decade later, he reflected on what had been an exceedingly difficult period in a 1995 Lapham's Quarterly article about why everyone in Hollywood hates screenwriters: 'Most screenwriters have never been an ongoing part of a motion-picture production, and most production personnel know it. They therefore know that a screenplay is a peculiar act of prophecy by someone who's no more licenced to work with a crystal ball than he is experienced in working on a film. That he would presume to write something that's going to cost fifty million dollars, be cast with actors he doesn't know and has never met, made with a director and crew he doesn't know and has never met, on locations that may or may not exist, in weather conditions that may make it impossible to shoot, can only confirm their suspicions about him. The mere fact of writing the screenplay is an act of astonishing arrogance and proves the writer should never have written it in the first place.'

Yet, despite his frequent fallings out of love with Hollywood, Towne remained available for work. He pitched ideas for The Mermaid (1983) to Warren Beatty and The Little Blue Whale (1985) to animator Don Bluth and, when neither landed, he did uncredited stints on William Friedkin's Chevy Chase comedy, Deal of the Century (1983), and Jonathan Demme's Swing Shift (1984), with Goldie Hawn reportedly hiring him for the latter to produce scenes that showed her character in a better light than Christine Lahti's.

After Beatty (as co-producer) had hired him to play Stan alongside Molly Ringwald and Robert Downey, Jr. in James Toback's The Pick-up Artist, Towne got to revise the text of one of America's most celebrated novelists, when Norman Mailer took a tilt at directing with Tough Guys Don't Dance (both 1987). A reunion with Roman Polanksi followed, as Towne made uncredited suggestions for the Harrison Ford thriller, Frantic (1988).

Having got to know Kurt Russell ('the best-hearted bad boy you're likely to meet') on Swing Shift, Towne cast him opposite Mel Gibson when he returned to the director's chair with Tequila Sunrise (1988). He had been sitting on the screenplay for several years and, when he announced that this was 'a movie about the use and abuse of friendship', many speculated about whether he was ruminating on his relationships with Nicholson, Evans, or Beatty - for whom the script had originally been written, with Harrison Ford, Alec Baldwin, Nick Nolte, and Jeff Bridges being considered as his co-stars. Sitting between the cop and the drug dealer who had known each other since childhood was a restaurant owner played by Michelle Pfeiffer (who is the subject of one of Cinema Paradiso's Getting to Know articles). But, even though audiences enjoyed watching to trio to the tune of $100 million, the reviews were mixed and Towne had to return to the day job.

In an interview with The New York Times, Towne revealed, 'The characters I write about are men who control events far, far less than events control them. My characters get caught, they try even though they don't prevail or even significantly influence events. These guys muddle through.' To an extent, he could have been describing his own career, especially after he started succumbing once more to his mysterious ailments. However, a rather unexpected door was about to open for him.

In the late 1980s, Towne became friends with Tom Cruise and he was asked to work up a story idea the pair had had about NASCAR racing. Producers Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer hired Top Gun (1986) director Tony Scott to give the visuals some add extra vrooom. But the three alphas spent the production butting heads, with the result that Cruise used the endless delays on Days of Thunder (1990) to get to know co-star Nicole Kidman (who is also profiled in a Getting to Know article).

Tensions were also high on the set of The Firm (1993), an adaptation of a John Grisham bestseller on which Towne worked with David Rabe and David Rayfiel. Charlie Sheen and Jason Patric had originally been lined up to play Harvard Law graduate Mitch McDeere, but producers Scott Rudin and John Davis pitched the project to Cruise on the set of Rob Reiner's A Few Good Men (1992). They wanted to cast Meryl Streep as Mitch's mentor, but Grisham's veto led to Gene Hackman being hired at the eleventh hour.

By this stage, Towne had moved on to help Warren Beatty make Love Affair (1994), with Annette Bening. Cinema Paradiso users will know the story from Leo McCarey's Love Affair (1939) and An Affair to Remember (1957), which had already been reworked by Nora Ephron as Sleepless in Seattle (1993). Beatty's version rather slipped through the cracks, but it deserves to be on disc, if only because it contains Katharine Hepburn's last performance.

Continuing his hit'n'miss existence, Towne failed to strike gold with his scripts for either Beverly Hills Cop III (which was written for John Landis by Steven E. de Souza) or The Night Manager (both 1994), an adaptation for Sydney Pollack of the John Le Carré thriller that would eventually be made for television in 2016, with Tom Hiddleston and Hugh Laurie starring for Susanne Bier. Yet, Tony Scott called to get Towne to give Michael Schiffer's screenplay for Crimson Tide (1995) a once over after Denzel Washington and Quentin Tarantino had faced off over the latter's uncredited rewrites.

Cruise remained a fan, however, and dialled Towne after he and Brian De Palma decided they didn't like Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz's original script for Mission: Impossible (1996). David Koepp had been expensively hired to redraft the scenario, but the star and director remained unhappy with the way the set-pieces they had conceived fitted into the narrative. This is where Towne came in, as he rethought the Prague opening, the twist in the middle, and the big finale, while Koepp and De Palma fleshed out the plot details. Clearly, Cruise appreciated Towne's input, as he was rehired for John Woo's Mission: Impossible 2 (2000) after William Goldman had walked away. 'All that's left of mine is the climax,' Goldman told an interviewer, 'the climbing up the rocks sequence. I couldn't come up with a good villain and Bob Towne did.' However, Towne himself conceded that the plot outline had already been agreed, along with several key action sequences, before he became involved.

As a favour to a friend, Cruise and partner Paula Wagner produced Towne's third film as a director. Co-written by Kenny Moore, Without Limits (1998) told the tragic story of distance runner Steve Prefontaine (Billy Crudup) and his coach, Bill Bowerman (Donald Sutherland), who would go on to co-found Nike after the athlete had lost his life in a car crash at the age of 24. Unfortunately, no one has thought to reissue the film on disc in an Olympic year, but it was barely seen on its release and recouped only $777,000 of its $25 million budget.

Michael Bay's $140 million disaster epic, Armageddon, had no such trouble raking in the cash, as it amassed $553.7 million. Jonathan Hensleigh and J. J. Abrams took the scripting credit after Tony Gilroy and Shane Salerno had adapted a story by Hensleigh and Robert Roy Pool. But Towne was brought in by Jerry Bruckheimer - along with Paul Attanasio, Ann Biderman, and Scott Rosenberg - as Touchstone sought ways to ensure that the story was as different as possible from Mimi Leder's comet collision saga, Deep Impact (both 1998).

Having taken the uncredited role of Professor Dates in E. Elias Merhige's Suspect Zero (2004), Towne was profiled by Sarah Morris in the art documentary, Robert Towne (2006), which complemented a giant painting installation in the lobby of Manhattan's Lever House. This proved to be a busy period, as Towne had found the funding to adapt John Fante's novel, Ask the Dust (2006), which he had proclaimed 'the best book about Los Angeles ever written'. Mel Brooks had acquired the rights and Towne offered to write the screenplay for free if he was allowed to direct. Tom Cruise and Paula Wagner helped him realise his dream, as he cast Colin Farrell and Salma Hayek in a drama set in the 1930s that was filmed on sets that were specially constructed on two football pitches in Capetown, South Africa.

Much to Towne's chagrin, the reviews were lukewarm and the takings meagre. But he was proud of his work, telling The New York Times, 'I think melodrama is always a splendid occasion to entertain an audience and say things you want to say without rubbing their noses in it. With melodrama, as in dreams, you're always flirting with the disparity between appearance and reality, which is a great deal of fun. And that's also not unrelated to my perception of my life working in Hollywood, where you're always wondering, "What does that guy really mean?"'

This underrated drama came in the middle of a fallow period, as a proposed remake of The 39 Steps (2003) went the same way as the four-part Robert Harris mini-series, Pompeii; the TV pilot, Compadre (both 2011); the features Next of Kin (2011) and The Battle of Britain (2011), which were respectively written for David Fincher and Graham King; and the teleplay, Dancing Bear (2018), which Towne had adapted for Mel Gibson from a James Crumley novel.

Being Robert Towne, however, he managed to keep his hand by writing two episodes of Welcome to the Basement (2012-) and becoming a staff writer and consulting producer on the final series of Mad Men (2007-15), the acclaimed series about the Madison Avenue advertising scene in 1950s New York. Towne's involvement landed him a third Writers Guild award, having been presented in 1997 with the group's Laurel Award for Screenwriting Achievement.

He still had a couple of surprises up his sleeve, too. In addition to the hook-up with David Fincher on the Chinatown prequel, Towne did nothing to challenge author Sam Wasson's contention that he had collaborated in secret for four decades with his Pomona College roommate, Edward Taylor. As Taylor wanted to keep out of the limelight to focus on his career teaching sociology and statistics at the University of Southern California, he had allowed Towne take all the credit for their joint efforts until his death in 2013. Yet, in a 1983 essay for a limited edition of the Chinatown screenplay, Towne had mentioned Taylor's visits to Catalina Island and had referred to him as his 'Jiminy Cricket, Mycroft Holmes and Edmund Wilson'.

Survived by brother Roger, daughters Katharine and Chiara, and second wife, Luisa Gaule, Towne wound up working on more films on which his name doesn't appear than on those where it does. He never harboured any literary ambitions, confiding in a 1991 essay for Esquire that he had only ever wanted to write for the screen. 'There are no novels or plays I'm itching to write,' he revealed, 'and there never have been. I love movies. I think movies best communicate whatever I have to say and show; or to put it another way, when what you want to show is what you have to say, you are pretty much stuck with movies as a way of saying it.' And you can't say fairer than that!

-

The Tomb of Ligeia (1964)

Play trailer1h 18minPlay trailer1h 18min

Play trailer1h 18minPlay trailer1h 18minVerden Fell: I tried to kill a stray cat with a cabbage, and all but made love to the Lady Rowena. I succeeded is squashing the cabbage and badly frightening the lady. If only I could lay open my own brain as easily as I did that vegetable, what rot would be freed from its grey leaves?

- Director:

- Roger Corman

- Cast:

- Vincent Price, Elizabeth Shepherd, John Westbrook

- Genre:

- Classics, Horror

- Formats:

-

-

The Last Detail (1973)

Play trailer1h 40minPlay trailer1h 40min

Play trailer1h 40minPlay trailer1h 40minMule Mulhall: I consider myself in jeopardy with you, man, understand? In jeopardy. This ain't no farewell party an' he ain't retirin'. Understand? He's a prisoner an' we're takin' 'im to the jailhouse. An' you have a tendency to forget that. You're a menace, man.

- Director:

- Hal Ashby

- Cast:

- Jack Nicholson, Randy Quaid, Otis Young

- Genre:

- Drama, Comedy, Classics, Action & Adventure

- Formats:

-

-

Chinatown (1974)

Play trailer2h 5minPlay trailer2h 5min

Play trailer2h 5minPlay trailer2h 5minJake Gittes: A memorial service was held at the Mar Vista Inn today for Jasper Lamar Crabb. He passed away two weeks ago.

Evelyn Mulwray: Why is that unusual?

Jake Gittes: He passed away two weeks ago and one week ago he bought the land. That's unusual.

- Director:

- Roman Polanski

- Cast:

- Jack Nicholson, Faye Dunaway, John Huston

- Genre:

- Drama, Thrillers, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

Shampoo (1975)

1h 45min1h 45min

1h 45min1h 45minJackie Shawn: Do you know why I used to get angry with you?

George Roundy: I wouldn't settle down.

Jackie Shawn: Cause you're always so happy - about everything.

George Roundy: I was?

Jackie Shawn: I found it rather unrealistic.

- Director:

- Hal Ashby

- Cast:

- Warren Beatty, Julie Christie, Goldie Hawn

- Genre:

- Comedy, Classics, Drama, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes (1984) aka: Greystoke / Greystoke: The 7th Earl Lord John Clayton, Tarzan of the Apes

Play trailer2h 11minPlay trailer2h 11min

Play trailer2h 11minPlay trailer2h 11minCapitaine Phillippe D'Arnot: I sensed we had a long and difficult journey ahead of us. Perhaps weeks of waiting for a ship that will give us passage to England. I will try to teach John some rudimentary manners and a greater understanding of the language. Like a father, I am resolved to empower to him all that I can. But never, not even for a moment, do I doubt that to take him back, is a perilous undertaking. For John but also for his family.

- Director:

- Hugh Hudson

- Cast:

- Christopher Lambert, Andie MacDowell, Ralph Richardson

- Genre:

- Classics, Action & Adventure, Drama

- Formats:

-

-

Tequila Sunrise (1988)

Play trailer1h 51minPlay trailer1h 51min

Play trailer1h 51minPlay trailer1h 51minGregg Lindroff: I don't know what it is about going to high school with someone that makes you feel you're automatically friends for life. Who says, who says friendship lasts forever? We'd all like it to, maybe. But maybe... it just wears out like everything else. Like tyres. There's just so much mileage in them and then you're riding around on nothing but air.

- Director:

- Robert Towne

- Cast:

- Mel Gibson, Michelle Pfeiffer, Kurt Russell

- Genre:

- Thrillers, Action & Adventure, Drama, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

Days of Thunder (1990)

Play trailer1h 42minPlay trailer1h 42min

Play trailer1h 42minPlay trailer1h 42minDr Claire Lewicki: Control is an illusion, you infantile egomaniac. Nobody knows what's gonna happen next: not on a freeway, not in an airplane, not inside our own bodies and certainly not on a racetrack with 40 other infantile egomaniacs.

- Director:

- Tony Scott

- Cast:

- Tom Cruise, Nicole Kidman, Robert Duvall

- Genre:

- Sports & Sport Films, Action & Adventure, Drama, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

The Firm (1993)

Play trailer2h 28minPlay trailer2h 28min

Play trailer2h 28minPlay trailer2h 28minEddie Lomax: That's my secretary. She is terrific. She's got a nutcase for a husband. He's a truck driver. He moved here to be close to Graceland. Reason why? He thinks he's Elvis. What do you think his name is? It's Elvis! Elvis Aaron Hemphill. I run across some strange things on this job. Some things you would never spray paint on an overpass.

- Director:

- Sydney Pollack

- Cast:

- Tom Cruise, Jeanne Tripplehorn, Gene Hackman

- Genre:

- Thrillers, Drama

- Formats:

-

-

Mission Impossible (1996) aka: Mission: Impossible

Play trailer1h 45minPlay trailer1h 45min

Play trailer1h 45minPlay trailer1h 45minJim Phelps: Well, you think about it Ethan, it was inevitable. No more cold war. No more secrets you keep from yourself. Answer to no one but yourself. Then, you wake up one morning and find out the President is running the country without your permission. The son of a b*tch, how dare he. Then you realise, it's over. You are an obsolete piece of hardware, not worth upgrading, you got a lousy marriage, and 62 grand a year.

- Director:

- Brian De Palma

- Cast:

- Tom Cruise, Jon Voight., Emmanuelle Béart

- Genre:

- Thrillers, Action & Adventure

- Formats:

-

-

Ask the Dust (2006)

Play trailer1h 52minPlay trailer1h 52min

Play trailer1h 52minPlay trailer1h 52minArturo Bandini: What does happiness mean to you Camilla?

Camilla: That you can fall in love with whoever you want to, and not feel ashamed of it.

- Director:

- Robert Towne

- Cast:

- Colin Farrell, Salma Hayek, Donald Sutherland

- Genre:

- Drama

- Formats:

-