As Hollywood casts its votes for the Academy Awards, there's as much chatter about who missed out on a nomination as there is about the actual nominees. It happens every year, so Cinema Paradiso takes time out from the red carpet to recall the great Oscar snubs.

The big problem with the Academy Awards is that, with the exception of Best Picture, there are only five slots available in the major acting and craft categories. It stands to reason, therefore, that excellence before or behind the camera is going to be overlooked each year. Moreover, Hollywood is a very sentimental and capricious town that tends to ignore popular opinion. Consequently, blockbusters that have thrilled audiences worldwide and raked in millions of dollars rarely get Oscar recognition outside the technical categories. It's a minor miracle, therefore, that Ryan Coogler's Black Panther has become the first comic-book spin-off to be nominated for Best Picture. But the history of the most prestigious prize in cinema is strewn with perceived injustices and the fuss started when the first nominees were announced in February 1928.

The First Decade

While everyone knew that Alan Crosland's The Jazz Singer (1927) had transformed motion pictures by ushering in the talkies, few in Hollywood thought it was much good. As a result, while Warner Bros were presented with an honorary award as a token gesture for 'revolutionising the industry', the film itself received only one nomination at the inaugural Academy Awards in May 1929, when Alfred A. Cohn was cited in the Best Adaptation category for reworking Samson Raphaelson's story, 'The Day of Atonement'. Perhaps because he had consigned dozens of silent stars to the scrap heap by blurting out cinema's first spoken line of dialogue, 'Wait a minute, wait a minute I tell yer, you ain't heard nothin' yet,' Al Jolson was overlooked for Best Actor, while Wings director William A. Wellman started a trend for snubbing the helmer of the Best Picture winner when he lost out to Frank Borzage for 7th Heaven (both 1927).

The first ceremony was an exclusive affair, with the winners knowing in advance that they would receive one of the golden statuettes designed by Cedric Gibbons. But the Oscars quickly became highly competitive, as they caught the public imagination and the studios realised that the annual awards were exceedingly good for business. In order to land the big prizes, therefore, the moguls started campaigning for their contracted artists and this lobbying by the Big Five meant that worthy achievements produced by the smaller studios were often ignored. The awards were often highly parochial, with foreign masterpieces like Abel Gance's Napoleon (1927) and Carl Theodor Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) being excluded. GW Pabst's Pandora's Box (1929) was also overlooked, even though its star, Louise Brooks, was an American.

There is a difference, of course, between being nominated and losing and missing out altogether. At the 3rd Academy Awards, therefore, Greta Garbo could feel unlucky at losing Best Actress to Norma Shearer (The Divorcee) after she made such a sensational entry into talking pictures in Clarence Brown's Anna Christie. But the real surprise of the year was the omission of Lew Ayres and Louis Wolheim from the Best Actor category for their work in Lewis Milestone's Best Picture winner, All Quiet on the Western Front. Marlene Dietrich's exclusion from Best Actress after her iconic turn in Josef von Sternberg's The Blue Angel (all 1930) also raised eyebrows. The same was true the following year when Edward G. Robinson and James Cagney were nixed for playing mobsters in Mervyn LeRoy's Little Caesar and William Wellman's The Public Enemy, while the curse of the horror movie (which still endures) meant no recognition for Bela Lugosi or Boris Karloff in Tod Browning's Dracula and James Whale's Frankenstein (both 1931).

Such was Hollywood's desire to detach itself from its silent past that Charlie Chaplin's City Lights (1931) and Modern Times (1936) failed to receive a single nomination between them. However, comic genius was rarely rewarded in the early 1930s, as the haphazard nature of the nomination process often limited the number of berths to three until five became the norm at the 8th Academy Awards in March 1936. It wasn't until the following year that supporting performances were recognised and, as a consequence, dozens of fine turns slipped through the Oscar net. Among those to lose out were Mae West for She Done Him Wrong (1933), Myrna Loy for The Thin Man, Bette Davis for Of Human Bondage (both 1934), Fred Astaire for Top Hat (1935), Jean Arthur for Mr Deeds Goes to Town (1936), Cary Grant for The Awful Truth and Carole Lombard for Nothing Sacred (both 1937).

Of course, it's all subjective, as why else would Garbo have failed to win for either Clarence Brown's Anna Karenina (1935) or George Cukor's Camille (1936) ? At least she was nominated for the latter performance, but she is one of the biggest names in screen history to have failed to win an Academy Award. Another is Alfred Hitchcock, who didn't make the shortlist for British gems like The 39 Steps (1935) and The Lady Vanishes (1938) and continued to miss out for landmark pictures like Notorious (1946), Vertigo (1958) and North By Northwest (1959), while also failing to convert nominations for Rebecca (1940), Lifeboat (1944), Spellbound (1945), Rear Window (1954) and Psycho (1960).

The absence of an award for special effects until 1939 also meant that pictures like Merian C. Cooper and Ernest Schoedsack's King Kong (1933) went ungarlanded, while short-lived awards like the one for Best Dance Direction bafflingly escaped the grasp of ace choreographer Busby Berkeley. A reluctance to allow animation into the Best Picture category also left Walt Disney to grin and bear the receipt of a special Oscar and seven miniature statuettes for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). Judy Garland also had to settle for an honorary award after failing to make the cut for Best Actress for her exquisite performance as Dorothy Gale in Victor Fleming's The Wizard of Oz (1939). But oversights abounded in what many consider to be Hollywood's Golden Year, as Charles Laughton (The Hunchback of Notre Dame), Barbara Stanwyck and William Holden (Golden Boy), Henry Fonda (Young Mr Lincoln), Ernst Lubitsch (Ninotchka), Marlene Dietrich (Destry Rides Again), Lon Chaney, Jr. (Of Mice and Men) and Merle Oberon (Wuthering Heights) failed to sufficiently impress their peers.

The Forties and Fifties

As Europe succumbed to conflict, the Academy Awards became more insular than ever. Yet, there still weren't enough free spots in the Best Actor category to recognised Cary Grant for his work in either George Cukor's The Philadelphia Story or Howard Hawks's His Girl Friday (both 1940). Indeed, Grant's co-star in the latter, Rosalind Russell, was also overlooked for feminising the role of reporter Hildy Johnson that had been played by Pat O'Brien in Lewis Milestone's The Front Page (1931). Another screwball classic fell foul of the electorate the following year, as neither Barbara Stanwyck nor Henry Fonda was deemed award-worthy for their majestic byplay in Preston Sturges's The Lady Eve (1941). Curiously, Stanwyck was nominated for her spiky, but less mesmerising display in Hawks's Ball of Fire, but there was clearly something rum going on that year, as neither Humphrey Bogart nor Peter Lorre were nominated for John Huston's prototype film noir, The Maltese Falcon, while Joseph Cotten failed to make the Best Supporting Actor cut for his work opposite Orson Welles in Citizen Kane (1941).

Cotten was also overlooked for Welles's follow-up, The Magnificent Ambersons, as a wave of patriotism swept the ceremony following the US entry into the Second World War. Perhaps that explains the decision to only nominate Ernst Lubitsch's gleeful romp, To Be Or Not to Be (both 1942), in the Best Score category, as a comedy set in Occupied Poland seemed a touch too risqué. Lubitsch was recognised the following year for Heaven Can Wait, but leading man Don Ameche missed out on a Best Actor nod, while Ingrid Bergman's Best Actress nomination was for Sam Wood's For Whom the Bell Tolls (both 1943) rather than for her peerless performance as Ilsa Lund in Michael Curtiz's Casablanca (1942). Twelve months later, Bergman would win for George Cukor's Gaslight, when the award should have gone to Barbara Stanwyck for Billy Wilder's simmering noir, Double Indemnity. At least Stanwyck was nominated, unlike her co-stars Fred MacMurray and Edward G. Robinson, and Judy Garland, who had produced the best performance of her career to date in husband Vincente Minnelli's Meet Me in St Louis (all 1944).

Oscar often exhibited a touch of snobbery when it came to B movies and Edgar G. Ulmer's masterly noir, Detour (1945), was not alone in being considered too unpolished for the major prizes. That said, technical ingenuity wasn't always rewarded, either, as Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's epic fantasy, A Matter of Life and Death (1946), was also passed over. The 19th Academy Awards also saw pictures of the quality of Charles Vidor's Gilda, Tay Garnett's The Postman Always Rings Twice, Howard Hawks's The Big Sleep, John Ford's My Darling Clementine and Frank Capra's It's a Wonderful Life (all 1946) prove not to have the right stuff for Best Picture. Powell and Pressburger were also shunned for Black Narcissus, although it did win awards for its inspired art direction and colour cinematography. Many felt that Kathleen Byron was worth a Best Supporting nod, while Jane Greer should have been recognised for playing an even more calculating femme fatale opposite Robert Mitchum and Kirk Douglas (neither of whom was recognised, either) in Jacques Tourneur's inky noir, Out of the Past (both 1947).

There are years when you have to wonder what films the Academy electorate has been watching. With the exception of Laurence Olivier making history by directing himself to the Best Actor award for Hamlet (1948). Yet, the same year saw stellar performances by John Wayne in Howard Hawks's Red River, Henry Fonda in John Ford's Fort Apache, John Garfield in Abraham Polonsky's Force of Evil, Anton Walbrook in Powell and Pressburger's The Red Shoes, and Humphrey Bogart in the John Huston duo, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and Key Largo - all of which were scorned. Then again, they also opted to ignore Orson Welles's The Lady From Shanghai and Max Ophüls's Letter From an Unknown Woman. Clearly the impact of the House UnAmerican Activities Committee's investigation into Communism in Hollywood focused attention elsewhere.

Decade's end saw Joseph L. Mankiewicz snag the Oscars for Best Director and Screenplay for A Letter to Three Wives. Yet, the estimable ensemble led by Linda Darnell was frozen out of the acting categories, as were James Cagney for Raoul Walsh's White Heat, Robert Ryan for Robert Wise's The Set-Up, John Dahl and Peggy Cummins for Joseph H. Lewis's Gun Crazy and John Wayne for John Ford's She Wore a Yellow Ribbon. But the Academy recognised the error of its ways in only nominating Cesare Zavattini's screenplay for Vittorio De Sica's seminal neo-realist saga, Bicycle Thieves, by creating the Best Foreign Film category to recognise the growing number of subtitled (or dubbed) pictures securing a Stateside release.

As the annual Oscar jamboree became essential viewing on the new television sets changing the face of American entertainment, Hollywood responded by producing pictures in widescreen, colour and stereophonic sound to lure patrons out of their living-rooms and back into movie theatres. The emphasis was still on monochrome intimacy at the start of the 1950s, however, as Joseph L. Mankiewicz's All About Eve set a new record with its 14 nominations. Yet, astonishingly, Compton Bennett's bang average adaptation of H. Rider Haggard's King Solomon's Mines (1950) kept Carol Reed's The Third Man (1949) out of the Best Picture running, while Graham Greene's screenplay and Anton Karas's zither score were similarly discarded. In another nose-thumbing to the Brits, Alec Guinness's exceptional display as the eight members of the D'Ascoyne family in Robert Hamer's Ealing gem, Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949), was deemed inferior to Louis Calhern's turn as Oliver Wendell Holmes in John Sturges's biopic, The Magnificent Yankee (1950).

When Humphrey Bogart finally won his Oscar for John Huston's The African Queen, many felt that Marlon Brando had been robbed for his Method performance in Elia Kazan's take on Tennessee Williams's play, A Streetcar Named Desire. But losing on the night isn't the same as being snubbed altogether, as Kirk Douglas and Alastair Sim found out after respectively excelling in Billy Wilder's Ace in the Hole and Brian Desmond Hurst's Scrooge (all 1951). The latter continued the tendency to overlook fantasy features and Robert Wise's The Day the Earth Stood Still and Christian Nyby and Howard Hawks's The Thing lost out because of a similar prejudice against science-fiction. Indeed, genre cinema has always done poorly at the Oscars and has long led to accusations of the AMPAS voters being overly elitist and/or middlebrow and out of touch with popular tastes.

They clearly took exception to having a mirror held up to themselves in Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen's Singin' in the Rain and Vincente Minnelli's The Bad and the Beautiful, as neither of these movie-making insights received a nomination for Best Picture. Indeed, the latter became the most decorated film not to be cited for the top prize after it took five awards. Given that Cecil B. DeMille's The Greatest Show on Earth is widely considered to be one of the least worthy Best Picture winners, their omission is all the more egregious. Marlene Dietrich was overlooked again, this time for Fritz Lang's Rancho Notorious and being out West similarly scuppered the prospects of Grace Kelly in Fred Zinnemann's High Noon (1952), Jean Arthur and Alan Ladd in George Stevens's Shane, Doris Day in David Butler's Calamity Jane and James Stewart in Anthony Mann's The Naked Spur. But the urban jungle did few favours for Lang's The Big Heat (all 1953), which failed to land a single nomination.

As Elia Kazan's enduringly divisive On the Waterfront took Best Picture at the 27th Academy Awards, questions were asked why Jean Negulesco's Three Coins in the Fountain, Edward Dmytryk's The Caine Mutiny and George Seaton's The Country Girl had been selected as its competition alongside Stanley Donen's Seven Brides For Seven Brothers when Alfred Hitchcock's Rear Window, George Cukor's A Star Is Born and Douglas Sirk's Magnificent Obsession had not. Sirk's All That Heaven Allows found itself in equally good company on the unwanted shelf the following year, alongside Charles Laughton's The Night of the Hunter, Robert Aldrich's Kiss Me Deadly and Walt Disney's Lady and the Tramp (all 1955). But the decade's biggest travesty saw both Akira Kurosawa's Seven Samurai (1954) and John Ford's The Searchers (1956) left out of the Best Picture stakes which was won by Michael Anderson's all-star adaptation of Jules Verne's Around the World in 80 Days.

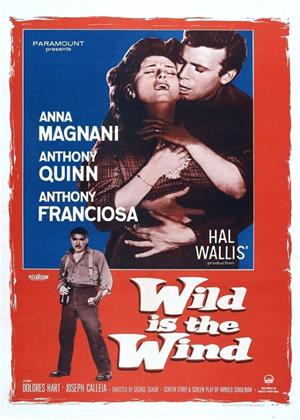

Among the numerous oddities to arise at the 30th Academy Awards, Stanley Kubrick's Paths of Glory and Alexander Mackendrick's Sweet Smell of Success were denied any nominations, while the Ingmar Bergman duo of The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries failed to feature in the Best Foreign Film category. Henry Fonda and Lee J. Cobb also deserved better after their towering performances in Sidney Lumet's 12 Angry Men, while few will ever understand why Anna Magnani was nominated for Best Actress for George Cukor's melodramatic Western, Wild Is the Wind, when compatriot Giulietta Masina was overlooked for her indelible display in husband Federico Fellini's Nights of Cabiria (all 1957). Similarly, the decision to snub Alfred Hitchcock, James Stewart and Kim Novak for Vertigo (1958) is equally perplexing, as is the exclusion of both Lee Remick and Marilyn Monroe from the Best Actress category for their contrasting contributions to Otto Preminger's Anatomy of a Murder and Billy Wilder's Some Like It Hot (both 1959), with the latter's failure to make the Best Picture cut also looking increasingly foolish with each passing year.

Oscar in a Time of Change

As the studios began to lose their grip on Hollywood and the restrictive Production Code was replaced by a ratings system that gave film-makers greater freedom of expression, the Oscars became temporarily trapped in a time warp, as the stars of yesteryear kept voting for the kind of films they had made over ones that reflected a changing world. Consequently, John Wayne's The Alamo landed a Best Picture nod in 1960 when Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho didn't. Unthinkably, Bernard Herrmann's shrieking strings also missed out on a Best Score nomination, while Anthony Perkins was snubbed for his chilling performance as Norman Bates. Fred MacMurray was also unlucky not to be recognised for his seedy turn as Shirley MacLaine's exploitative boss in Billy Wilder's The Apartment (all 1960).

Another acerbic Wilder comedy provided James Cagney with a scorching supporting role on One, Two, Three. But he was overlooked at the 34th Academy Awards, along with Albert Finney for Karel Reisz's Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, Marcello Mastroianni for Federico Fellini's La Dolce Vita, Sidney Poitier for Daniel Petrie's A Raisin in the Sun, and Clark Gable and Marilyn Monroe for John Huston's The Misfits (all 1961), which turned out to be the pair's final picture. There were also acting omissions aplenty the following year, with Frank Sinatra's work in John Frankenheimer's The Manchurian Candidate and Joan Crawford's marvellous display in Robert Aldrich's What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? being the most glaring. However, the major objections came in the Best Picture category, as The Longest Day, Mutiny on the Bounty and The Music Man were preferred to the aforementioned titles, as well as François Truffaut's Jules et Jim, John Ford's The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and Arthur Penn's The Miracle Worker (all 1962), which brought Oscars for both Anne Bancroft and Patty Duke as Annie Sullivan and Helen Keller.

The sheer scale of Joseph L. Mankiewicz's Cleopatra and the multi-directed How the West Was Won browbeat the electors into handing out Best Picture nominations for 1963, but the only obvious replacement was Federico Fellini's masterly 8½ (1963), which should again have earned a Best Actor nod for Marcello Mastroianni. Even though her singing was dubbed by Marni Nixon, Audrey Hepburn should most certainly have been nominated for her performance as Eliza Doolittle in George Cukor's My Fair Lady, while it's difficult to fathom why the Best Song category didn't contain a Beatle track from Richard Lester's A Hard Day's Night (both 1964) - or from Help! the following year. Cases could also have been made for Dirk Bogarde for Best Actor in Joseph Losey's The Servant (1963) and for David Tomlinson for his supporting turn as Mr Banks in Robert Stevenson's Mary Poppins (1964).

While Oscar continued to discount the James Bond franchise, it also steered clear of contentious titles like Roman Polanski's Repulsion, which should certainly have earned Catherine Deneuve a Best Actress nod. Christopher Plummer and Omar Sharif can also feel aggrieved at having been passed over for Robert Wise's The Sound of Music and David Lean's Doctor Zhivago (all 1965). Liv Ullmann would have shared their sentiments after missing out for her outstanding performance in Ingmar Bergman's Persona (1966), although Orson Welles would have expected to be snubbed for his work as both actor and director on the Shakespearean epic, Chimes At Midnight (1965).

Sidney Poitier was the big loser at the 40th Academy Awards, as he didn't snare a single nomination for his performances in James Clavell's To Sir, With Love, Norman Jewison's In the Heat of the Night and Stanley Kramer's Guess Who's Coming to Dinner. However, Paul Simon was probably miffed at 'Mrs Robinson' from Mike Nichols's The Graduate failing to make the Best Song shortlist, while Luis Buñuel and Catherine Deneuve's exclusions for Belle de Jour (all 1967) suggested that the sixties hadn't really started to swing in Hollywood, in spite of the Summer of Love. This contention was confirmed by the spurning of Stanley Donen's Two For the Road and John Boorman's Point Blank (both 1967) and Richard Lester's Petulia and Noel Black's Pretty Poison (both 1968). Indeed, while the rest of the world was seeking deeper meanings in Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, the Academy decided to omit it from the Best Picture nominations, along with cult favourites like Roman Polanski's Rosemary's Baby, John Cassavetes's Faces and Peter Bogdanovich's Targets (all 1968).

The talk was of a New Hollywood at the end of the 1960s, but trailblazers like Dennis Hopper's Easy Rider and Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch (both 1969) had to make do with nominations in the minor categories. Signs that the Western was also heading towards the cinematic sunset were also evident, as Sergio Leone's Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) was snubbed entirely and neither Paul Newman nor Robert Redford was nominated for their stellar displays in George Roy Hill's Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). The trend continued as Dustin Hoffman's remarkable performance in Arthur Penn's Little Big Man (1970) was overlooked, as was Warren Beatty in Robert Altman's McCabe and Mrs Miller. They were not alone in missing out in 1972, however, as Malcolm McDowall in Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange, Cybill Shepherd in Peter Bogdanovich's The Last Picture Show, Ruth Gordon in Hal Ashby's Harold and Maude, Clint Eastwood in Don Siegel's Dirty Harry, Jenny Agutter in Nicolas Roeg's Walkabout, and Elaine May in the self-directed A New Leaf (all 1971) failed to find enough enthusiastic supporters.

The following spring saw several more fine actors slip between the cracks, including John Cazale in Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather, Barbra Streisand in Peter Bogdanovich's What's Up, Doc?, Stacy Keach in John Huston's Fat City, Jon Voight and Ned Beatty in John Boorman's Deliverance, and Michael York in Bob Fosse's Cabaret (all 1972). But the focus fell in 1974 on the failure of Terrence Malick's Badlands, Martin Scorsese's Mean Streets, Nicolas Roeg's Don't Look Now, Robert Altman's The Long Goodbye and Woody Allen's Sleeper (all 1973) to conjure a single nomination between them. Gene Hackman was also somehow overlooked for his gripping depiction of paranoia in Coppola's The Conversation, as was Warren Beatty for his work in another Watergate-era conspiracy thriller, Alan J. Pakula's The Parallax View (both 1974).

Beatty missed out again for Hal Ashby's Shampoo, in a year that also saw snubs for Robert Mitchum in Dick Richards's Farewell, My Lovely, Tim Curry in Jim Sharman's The Rocky Horror Picture Show, and Sean Connery and Michael Caine in John Huston's The Man Who Would Be King. The latter pair rather cancelled each other out, as was probably the case with Richard Dreyfus, Robert Shaw and Roy Scheider in Jaws (all 1975). But, while Steven Spielberg was entitled to feel slighted at missing out on a Best Director nomination, it's hard to fault a line-up that included Robert Altman (Nashville), Federico Fellini (Amarcord), Stanley Kubrick (Barry Lyndon) and Sidney Lumet (Dog Day Afternoon), as well as winner Miloš Forman for One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest.

Martin Scorsese was also cold-shouldered the following year for Taxi Driver, as Lina Wertmüller became the first woman to be nominated for Best Director for Seven Beauties. Harvey Keitel was also denied a Best Supporting nod, as was Zero Mostel for Martin Ritt's fascinating HUAC saga, The Front. But it was Spielberg with cause for complaint at the 50th Academy Awards when Close Encounters of the Third Kind proved surplus to requirements for Best Picture. The most flagrant snubs that year, however, came in the Best Song category, as nothing from the soundtrack to John Badham's Saturday Night Fever was judged up to standard and neither was John Kander and Fred Ebb's karaoke favourite from Scorsese's New York, New York (all 1977).

The treatment of another John Travolta musical caused eyebrows to raise the following year when none of the much-loved cast of Randal Kleiser's Grease received a nomination. Brad Davis in Alan Parker's Midnight Express, John Belushi in John Landis's Animal House and Richard Pryor in Paul Schrader's Blue Collar (all 1978) also failed to find favour, But the decade ended with the curious exclusion of Woody Allen's Manhattan from the Best Picture and Director categories and the unforgivable omission of Gordon Willis from Best Cinematography. Elsewhere, blockbusters as different as Ridley Scott's Alien and Blake Edwards's 10 suffered the curse of the popular picture, while Marlon Brando was seemingly punished for his antics on Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now (all 1979) when co-star Robert Duvall pipped him to a spot on the Best Supporting Actor roster.

Win 6 months of free subscription by guessing Oscar winners! To take part in this competition, all you have to do is vote on each category. Whoever predicts the highest number of winners will get 6 months of free rentals with CinemaParadiso.co.uk. The competition will close at 12:00 on Sunday 24 February 2019 so hurry up and cast your vote!