Billy Wilder, Film Director

Six decades ago, Billy Wilder made screen history when he became the first person to win Oscars for producing, writing and directing a single film. Starring Jack Lemmon and Shirley MacLaine, The Apartment (1960) remains as relevant as ever for its insights into the misuse of power in the workplace. But, for a film-maker who is best remembered for his acerbic comedies, Wilder had a habit of exposing the seedier side of American society.

Despite being a key link between silent cinema and the blockbuster era, Billy Wilder outlived his time. For 21 years, until he was well into his 90s, he went to his office to work on projects that never came to fruition because Hollywood executives were too wrapped up in the profit culture that continues to dominate the American movie business. Just think of the possible gems we might now be able to enjoy from Cinema Paradiso had someone in a suit shown a little faith in a man who had converted three of his 12 Oscar nominations for Best Screenplay and two of his eight citations for Best Director. Fourteen performers owed their Academy Award nominations to Wilder, yet the modest box-office showing of Buddy Buddy (1981) consigned him to the margins of an industry he had helped to shape, as a writer for hire, a contract director and an independent hyphenate.

The Cake Shop At Sucha Beskidzka

On 22 June 1906, Max Wilder was visiting the cake shop he managed on the station platform at Sucha Beskidzka in Galicia when his wife, Eugenia, went into labour. As his brother had been named Wilhelm after his paternal grandfather, the newborn was called Samuel in honor of his mother's father. But he was always known as 'Billie' because Genia had become besotted with Buffalo Bill Cody during her short stay in New York.

As Jewish citizens of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Wilders decided towards the end of the Great War to leave the café they had opened in the Polish city of Kraków and relocate to Vienna. The capital was a hotbed of discontent following the removal of the Hapsburg dynasty, but the Wilders found a niche in republican Austria and Billie was destined to go to law school when, in 1925, he rebelled and joined Die Stunde as a tabloid reporter.

In later years, Wilder would concoct stories of interviewing Sigmund Freud, Richard Strauss, Arthur Schnitzler and Alfred Adler in a single day. But he was just a jobbing journalist, who made use of his fixation with American culture to snag an assignment to interview bandleader Paul Whiteman when he came to Vienna in 1926. Impressing the visitor with his knowledge and enthusiasm, Wilder agreed to act as an interpreter during the orchestra's forthcoming engagement in Berlin.

Having decided to stay in Weimar Germany, however, Wilder found gainful employment hard to come by and the 20 year-old was forced to supplement his income as a crime reporter on the Berliner Nachtausgabe by working as a taxi dancer at the Hotel Eden. This was a regular haunt of the novelist Erich Maria Remarque and Wilder used to tell the story that he had tried to talk him out of writing the classic novel about life in the trenches, which won the Academy Award for Best Picture when filmed by Lewis Milestone as All Quiet on the Western Front (1930). But he was found out when he told his mother that he had changed his name to Thornton Wilder and sent her rave reviews of his new book, The Bridge of San Luis Rey, which has been filmed three times (1929, 1944 and 2004), although no version is currently available to rent.

Wilder Days in Weimar

Never one to waste good material, Wilder published a series of stories about his Eden exploits and these led to offers from a range of newspapers and magazines. Moreover, he also started ghostwriting silent film scenarios after being bowled over by Sergei Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin (1925), which showed him a very different side of cinema after having been a boyhood fan of such cowboy stars as Bronco Billy Anderson and William S. Hart, as well as slapstick clowns like Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, Wilder was also was fortunate in making the acquaintance of Carl Meyer, who had scripted such major works of German Expressionism as Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920) and FW Murnau's The Last Laugh (1924).

For the most part, Wilder churned out uncredited scenes for the prolific screenwriter Franz Schultz, who had helped boost the popularity of British actress Lilian Harvey with Wilhelm Thiele's The Three From the Filling Station (1930), which had reinforced Germany's reputation in the early talkie era for musicals. This would be further enhanced during the Third Reich, as Rüdiger Suchsland reveals in the excellent documentary, Hitler's Hollywood (2017). But both Wilder and Schultz had long fled by this time, along with the likes of Joe May (who had directed the landmark realist drama, Asphalt, 1929) and Joe Pasternak, the producer who would help save Universal Studios during the Great Depression in conjunction with singing child star Deanna Durbin, whose wonderful 'Little Miss Fix-It' comedies (such as Henry Koster's One Hundred Men and a Girl, 1937) are available to rent from Cinema Paradiso.

While still in Berlin, Wilder found himself in the good books of Universal chief Carl Laemmle when he wrote The Daredevil Reporter (1929) for his director nephew, Ernst Laemmle, and the fading cowboy star, Eddie Polo. But Wilder would quickly distance himself from his sole solo script and took much greater pride in his contribution to People on Sunday (1929), a mini-city symphony that was co-directed by Robert Siodmak and Edgar G. Ulmer from a story by Curt Siodmak and was lit and photographed by Fred Zinnemann and Eugen Schüfftan.

Around this time, Wilder also befriended aspiring actress Marlene Dietrich, after he wrote a set report for a glossy magazine about Maurice Tourneur's The Ship of Lost Souls (1929). Such contacts led to Wilder being hired by UFA for such pictures as Siodmak's The Man in Search of His Murderer (1931). The same year also saw Wilder team with Emeric Pressburger on Gerhard Lamprecht's adaptation of Erich Kästner's bestselling children's adventure, Emil and the Detectives, which starred Rolf Wenkhaus as Emil Tischbein, the young boy who is drugged on a train by a stranger who steals the money intended for his grandmother in Berlin.

Over the next two years, Wilder would contribute to screenplays for some of Weimar's biggest female stars: Käthe von Nagy (Her Grace Commands, 1931); Mártha Eggerth (Once There Was a Waltz & The Blue of Heaven, both 1932) and Lilian Harvey (Happy Ever After, 1932). By the time Hans Steinhoff's Madame Wants No Children (1933) was released, however, Adolf Hitler had become Chancellor and Wilder joined the exodus of those fearing for their safety under the Nazis.

He fled to Paris, where he shared lodgings with Hungarian actor Peter Lorre and composers Franz Waxmann and Friedrich Hollander, who had famously written the score for Josef von Sternberg's The Blue Angel (1930). Although he spoke passable French, Wilder wasn't able to find screenwriting work and reluctantly made his directorial debut with Bad Seed (1934), a racy comedy about bored rich boy Pierre Mingland and his involvement with Danielle Darrieux and her gang of car thieves. But Wilder was convinced that his future lay in writing rather than directing and he hoped to fulfil his ambitions by relocating to Hollywood.

Billy With a Y

Having changed the spelling of his childhood nickname, Billy Wilder began making plans for the future. Using his UFA contacts, he started sending story ideas to the bigger Hollywood studios and was delighted when Joe May persuaded Columbia to buy the outline to something called Pam Pam. Sailing on the RMS Aquitania in order to learn English on the voyage, Wilder made it clear that he was more interesting in writing than directing. He moved into digs with Peter Lorre and found himself reunited with Franz Schultz on One Exciting Adventure (1934) and Lottery Lover (1935) at the Fox Film Corporation after receiving his first American credit for fellow exile William Dieterle's Adorable (1933).

As he was still mastering the language, Wilder often found himself writing in pairs or teams and came to prefer having a collaborator to bounce ideas off. Perhaps the most significant of his early assignments was Joe May's take on Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein's musical, Music in the Air (1934), which introduced him to Gloria Swanson, who would come out of retirement in 1950 to headline Wilder's scathing critique of the studio system. However, Wilder's tenure in the United States was anything but secure and, when his six-month visa ran out, he had to cross into Mexico in order to get new papers. He later mined his experience for Mitchell Leisen's Hold Back the Dawn (1941), in which Charles Boyer plays a Romanian gigolo who marries American teacher Olivia De Havilland in order to get his Green Card.

In 1937, Paramount bought Wilder's story for Champagne Waltz and director-cum-production chief Ernst Lubitsch was so taken by the Austrian émigré that he offered him a contract. Moreover, he teamed him with Charles Brackett, a Harvard Law graduate and member of the Algonquin Round Table, to script Bluebeard's Eighth Wife (1938), a sparkling screwball comedy set on the French Riviera that sees impoverished aristocrat's daughter Claudette Colbert teach millionaire Gary Cooper a lesson when she discovers that he has been married seven times before. Stippled with examples of the famed 'Lubitsch Touch', the picture proved such a hit that Wilder and Brackett were entrusted with Colbert's next assignment, Mitchell Leisen's Midnight (1939), in which she plays an American showgirl in Paris, who poses as a Hungarian countess in the hope of landing a rich husband only to promptly fall for penniless cabby, Don Ameche.

Not everything Wilder produced in this period was of the same calibre as these comic gems, with the Jackie Cooper vehicle, What a Life (1939), and the Bing Crosby musical, Rhythm on the River (1940), being largely forgotten. In between them, however, came a reunion with Lubitsch on Ninotchka (1939), in which Greta Garbo famously laughed while playing Nina Ivanovna Yakushova, a dour Communist commissar who comes to Paris to discipline pleasure-seeking diplomats Iranoff (Sig Ruman), Buljanoff (Felix Bressart) and Kopalski (Alexander Granach), only to fall in love with the smooth-talking Count Léon d'Algout (Melvyn Douglas). Melchior Lengyel earned an Oscar nomination for his three-line Original Story, while Wilder and Brackett were also recognised for their witty dialogue.

This proved to be their last collaboration with the German director. But, for the rest of his life, Wilder kept a plaque in his office that read: 'How Would Lubitsch Do It?' It would be a question he would keep asking himself after growing increasingly frustrated with the way in which lesser talents handled his scripts. Having reunited with Leisen for the Spanish Civil War drama, Arise, My Love (1940), and been involved in devising the storylines for Julien Duvivier's Tales of Manhattan (1942), Wilder was inspired to turn director himself after watching Howard Hawks on the set of Ball of Fire (1941), another screwball masterclass that reworked the story told in Walt Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) to show how a nightclub singer named Sugarpuss O'Shea (Barbara Stanwyck) seeks sanctuary from the New York police with unworldly professor Bertram Potts (Gary Cooper), who is compiling an encyclopedia of human knowledge with six bachelor colleagues.

Eighteen years later, Wilder would return to the theme of laying low in one of his biggest hits. For now, however, the newly naturalised American contented himself with giving the concept a gently tweak in making his Hollywood directorial bow with The Major and the Minor (1942), which drew on Edward Childs Carpenter's 1923 play, Connie Goes Home, for the story of how scalp masseuse Susan Applegate (Ginger Rogers) disguises herself as a 12 year-old girl in order to avoid paying full fare on the train and stumbles into the compartment of Major Philip Kirby (Ray Milland), who is so touched by Su-Su's sob story that he takes her under his wing at the military academy where fiancée Pamela Hill (Rita Johnson) soon becomes suspicious.

Despite the positive notices, Wilder was determined not to be pigeonholed and opted to base his follow-up on Hotel Imperial (1927), Swede Mauritz Stiller's adaptation of a 1917 Lajos Biró's play that had focused on life in the Hapsburg Empire during the Great War. Again co-scripted by Charles Brackett, Five Graves to Cairo (1943) centres with a mix of wit and suspense on the efforts of British tank trooper John J. Bramble (Franchot Tone) to discern the battle plans of German Afrika Korps commander Irwin Rommel (Erich von Stroheim) while hiding out in the remote Western Desert inn run by Farid (Akim Tamiroff) and his French maid, Mouche (Anne Baxter).

Of Paramount Importance

During the Golden Age of Hollywood, each studio had its own personality. As home to numerous European exiles, Paramount had developed a reputation for continental elegance. But Wilder was a keen student of his adopted country and, during a seven-year streak of exceptional pictures, he cast a keen outsider's eye over the darker recesses of American society. In the process, he helped change the tone of US cinema.

First published as a serial in Liberty magazine in 1936, James M. Cain's novella, Double Indemnity, was supposed to be unfilmable, as the Production Code Authority objected to just about every aspect of its seething study of lust, greed and murder. However, Wilder convinced the Paramount front office to hire hard-boiled novelist Raymond Chandler to help him concoct a screenplay. The pair didn't get on, but they found a way to convey the sheer immorality of the steamy relationship between insurance salesman Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray) and unhappily married client, Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck). Couched as a flashback, as the dying Neff dictates a confession for colleague Barton Keyes (Edward G. Robinson), the feature built on the look and feel of John Huston's prototype film noir, The Maltese Falcon (1941), which had been adapted from a bestseller by another pulp master, Dashiell Hammett.

Yet, having drawn on German Expressionist techniques to enable John Seitz's inky monochrome photography to turn the sun-kissed Los Angeles into a shadowy netherworld, Wilder changed tack in adopting an uncompromising realist approach in adapting Charles R. Jackson's novel, The Lost Weekend (1945). Shooting clandestinely on the streets of New York, Wilder and Seitz pitched alcoholic writer Don Birnam (Ray Milland) into the real world and, thus, made his plight all the more affecting, as he resorts to trying to pawn his typewriter in order to get money for booze.

The downbeat drama also had a profound effect on Wilder's private life, as he met Audrey Young during the shoot and they married in June 1949, three years after he had divorced first wife, Judith Coppicus, who was the mother of his daughter, Victoria. While Double Indemnity had failed to convert any of its seven nominations, this pioneering 'problem picture' allowed Wilder and Brackett to double up victoriously as writer-director and writer-producer, while Ray Milland took the prize for Best Actor. Seitz and editor Doane Harrison were unlucky to miss out, although composer Miklós Rósza had the unusual compensation of beating himself with his score for Alfred Hitchcock's Spellbound (1945).

Curiously, Hitch and Wilder would find themselves connected in a common enterprise towards the end of the Second World War. As Andre Singer reveals in the 2014 documentary, Night Will Fall, Hitchcock had agreed to help producer Sidney Bernstein edit the footage taken of the liberation of the Nazi death camps to alert the world to the hideous reality of the Holocaust. However, delays resulted in the project being shelved and Wilder was given access to the newsreel material to produce Death Mills (1945) for the US War Department. He also supervised the editing of Hanuš Burger's German-language version, Die Todesmühlen, which was also screened in Wilder's Austrian homeland. Much of the imagery he used can be seen in German Concentration Camps Factual Survey (2014).

What made this assignment all the more excruciating for Wilder was the fact that his mother, stepfather Bernard Siedlisker and grandmother Balbina Baldinger had all perished during the Shoah. He died thinking they had been murdered at Auschwitz, but they actually lost their lives respectively in Plaszow, the Nowy Targ ghetto and Belzec. As a colonel in the Psychological Warfare Division of the Occupational Government, Wilder was asked to prepare a report on the DeNazification of the German film industry and how it could be reformed to produce wholesome entertainments that promoted democratic values.

Once again, Wilder was able to take painful personal incidents and turn them into potent cinema, as A Foreign Affair (1948) teamed Jean Arthur and Marlene Dietrich, as a naive congresswoman investigating profiteering in postwar Berlin and a a torch singer who is anything but proud of her past. At one point, Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart's 'Isn't It Romantic?' plays on the soundtrack over shots of bombsites across the ravaged city, as Wilder seeks to show complacent Americans the real cost of their victory.

He came closer to home in Sunset Boulevard (1950), which had the audacity to be narrated by a corpse in a Tinseltown swimming pool. Collaborating for the last time, Wilder and Brackett were joined in the writers' room by DM Marshman, Jr. and the trio collected an Academy Award for their story about Joe Gillis (William Holden), an ambitious screenwriter who hopes to get his big break by exploiting faded star Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) when she hires him to polish the script for her comeback picture about Salome. With Erich von Stroheim playing Norma's butler and ex-husband, Max von Mayerling, Wilder was able to use footage from Von Stroheim's 1928 teaming with Swanson on Queen Kelly. But the nostalgia left a sour taste, as Wilder exposed the cruelty, cynicism and hypocrisy of the movie colony by casting such fallen idols as Buster Keaton, Anna Q. Nilsson and HB Warner as themselves in the poignant bridge party scene.

Wilder had upset many by reportedly dismissing the Hollywood Ten who had been blacklisted during HUACs Communist witch-hunt by declaring, 'Of the Ten, two had talent, and the rest were just unfriendly.' But even those who supported the purge turned on him over his hostile depiction of their lifestyle, with MGM chief Louis B. Mayer speaking for many when he seethed, 'This Wilder should be horsewhipped!' Nevertheless, Sunset Boulevard received 11 Oscar nominations, with production designer Hans Dreier and composer Franz Waxman winning their categories.

Rather than meekly tug a forelock, however, Wilder turned his gimlet gaze on the Fourth Estate that had backed him throughout this unflinchingly provocative phase of his career. Producing himself for the first time, Wilder joined forces with jobbing writers Lesser Samuels and Walter Newman on Ace in the Hole (1951), which follows the efforts of journalist Chuck Tatum (Kirk Douglas) to make his name on the Albuquerque Sun-Bulletin by cutting a deal with Sheriff Kretzer (Ray Teal) to prolong the rescue of a local man who has been trapped in a collapsed cave so that they can make the national news and put New Mexico on the map.

The pitiless way in which Tatum manipulates both the situation and worried wife Lorraine Minosa (Jan Sterling) over six excruciating days may seem par for the course in our tabloid times. But the American press corps and the public were shocked by the bleakness of Wilder's worldview and, for the first time in his directorial career, he had to endure a box-office setback, even though the film has since been hailed as a classic that was way ahead of its time.

A Diamond in the Rough

Following his exertions in West Germany in the immediate aftermath of the war, Wilder had felt the need to salvage some of his homeland's pride and had returned to Hollywood to make The Emperor Waltz (1948). Based on a true story, the action follows salesman Virgil Smith (Bing Crosby), as he tries to persuade the ageing Franz Josef (Richard Haydn) to buy a gramophone so that his subjects would follow suit. As a boy, Wilder had accompanied his father to the 86 year-old emperor's funeral in 1916 and he had been struck by the dignity of the young Crown Prince Otto walking behind the coffin. Around the time he made this film, Wilder was asked to give a distinguished visitor a guided tour of the Paramount lot and he turned out to be the prematurely aged Otto von Hapsburg, who was ekeing a living as a college lecturer on international relations.

This underrated picture, which co-stars Joan Fontaine as Countess Johanna Augusta Franziska is available from Cinema Paradiso as part of a Bing Crosby double bill. Wilder never reverted to such whimsy again, although he returned to Austria for Stalag 17 (1953), which drew on the Broadway play that Donald Bevan and Edmund Trzcinski had based upon their exploits in Stalag 17B during the war. Scripting with Edwin Blum, Wilder set the teasing action in a camp on the River Danube, where the cynical JJ Sefton (William Holden) is suspected of being in cahoots with the guards after the discovery of a secret tunnel. Cannily, the Oscar-nominated Wilder cast compatriot and fellow director Otto Preminger as commandant Colonel von Scherbach, but Holden stole the show and was rewarded with the Academy Award for Best Actor.

He got to show his gratitude to Wilder alongside Humphrey Bogart and Audrey Hepburn in Sabrina (1954), which saw the director-producer hook up with Ernest Lehmann to adapt Samuel A. Taylor's play, Sabrina Fair. In fact, three-times married playboy David Larrabee (Holden) is something of a heel and he only realises that chauffeur's daughter Sabrina Fairchild (Hepburn) is in love with him when he discovers that she is idolised by his serious older brother, Linus (Bogart). When Sydney Pollock remade Sabrina in 1995, he dusted down the original scenario before casting Harrison Ford and Greg Kinnear as the siblings competing for the affections of Julia Ormond.

This grown-up fairytale would prove to be Wilder's Paramount swan song and he would studio hop for much of the next quarter century. He would reunite with Hepburn for Love in the Afternoon (1957), another age-gap romance that teamed her with Gary Cooper for an adaptation of the Claude Anet novel, Ariane, Young Russian Girl. Sadly, this Parisian charmer co-scripted by IAL Diamond isn't currently available to rent, which is a shame as this Romanian-born writer would become Wilder's partner on 11 more screenplays (only two fewer than his tally with Brackett). Neither is The Spirit of St Louis (1957), a reconstruction starring James Stewart of Charles Lindbergh's epic 1927 flight across the Atlantic that Wilder had adapted with Charles Lederer and Wendell Mayes from the flier's Pulitzer Prize-winning memoir.

However, Wilder's third feature of a productive 1957 can be rented from Cinema Paradiso. He was particularly proud of the fact that Agatha Christie considered his version of Witness For the Prosecution to be among the best screen adaptations of her work. Co-writers Larry Marcus and Harry Kurnitz must take some of the credit, especially as the latter amusingly claimed that there were two Billy Wilders: 'Mr Hyde and Mr Hyde'. But Wilder alllowed a stellar cast to play to the hilt, as cantankerous lawyer Sir Wilfrid Robarts (Charles Laughton) ignores the warnings of his nurse, Miss Plimsoll (Elsa Lanchester), to conduct the Old Bailey defence of Leonard Vole (Tyrone Power), whose German wife, Christine (Marlene Dietrich), swears he is innocent of the murder of a rich widow who had made him the chief beneficiary of her will. Ralph Richardson (1982) and Toby Jones (2016) would subsequently relish the Robarts role in small-screen remakes.

Yet, while such traditional entertainments could still draw audiences at a time when increasingly large numbers preferred to stay home and watch television rather than go to the pictures, popular culture was undergoing a sea change and Wilder was alert enough to move with the times. In the year that rock'n'roll reared its head, he enlisted George Axelrod to help adapt his Broadway hit, The Seven Year Itch (1955), and rattled the censors' cage by having Marilyn Monroe's white dress billow up as a train passed under a ventilation grate.

Marilyn was playing the nameless girl who moves into the New York building where Richard Sherman (Tom Ewell) is enduring the long, hot summer while his wife and son are holidaying in Maine. Ewell would find himself playing a similar foil to Jayne Mansfield in Frank Tashlin's The Girl Can't Help It (1956). Likewise filmed in DeLuxe colour and CinemaScope, this similarly leering chauvinist comedy boasted music by Little Richard, Fats Domino and Gene Vincent. But it was syncopated jazz rather than rhythm and blues that gave Wilder the chance to cock another snook at the Hays Office.

A Twist of Lemmon

When United Artists presented Some Like It Hot (1959) to the Production Code guardians, they must have known it didn't stand a chance of receiving the certificate of approval necessary to secure a universal release. However, Wilder and Diamond's mischievously frank discussion of a range of sex-related issues proved part of the picture's appeal, as jazz musicians Joe (Tony Curtis) and Jerry (Jack Lemmon) are forced to pose as Josephine and Daphne in order to lie low with an all-female band after witnessing the St Valentine's Day Massacre. There was nothing new in a male movie character donning women's clothing, but Wilder toyed with notions of identity and desire through the relationships that the fugitives forge with singer Sugar Kane (Marilyn Monroe) and eccentric millionaire Osgood Fielding III (Joe E. Brown).

Wilder missed out on the Oscar for Best Director, while Jack Lemmon was overlooked for Best Actor, as William Wyler's Ben-Hur went on the rampage at the 32nd Academy Awards. Intriguingly, Michael Gordon's chaste romcom, Pillow Talk (both 1959) took the screenplay prize. But Wilder and Diamond refused to tone down their approach and their stubbornness paid off when The Apartment (1960) converted half of its 10 nominations in bringing Wilder the triple crown of Best Picture, Director and Original Screenplay. Once again, Lemmon was pipped on the night, as were co-stars Shirley MacLaine and Jack Kruschen, although the latter was fortunate to have been nominated in preference to Fred MacMurray, who excels as entitled insurance boss Jeff D. Sheldrake, who uses the apartment belonging to office underling CC Baxter to pursue his extramarital affair with elevator operator, Fran Kubelik.

The sight of Lemmon straining spaghetti through a tennis racket helped fix the film in the popular imagination. But there was a sour sadness about the story, which was reinforced by the dehumanising office interiors created by the Oscar-winning French production designer, Alexandre Trauner. Indeed, its themes have acquired a new relevance in the age of #MeToo and Time's Up and it's fascinating to view The Apartment alongside such recent exposés of workplace harassment as Jay Roach's Bombshell and Kitty Green's The Assistant (both 2019).

While working on the film, Wilder found himself staying near the United Nations headquarters in New York and hatched the idea of setting a Marx Brothers comedy in the building. Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy had baulked at Wilder's proposal for a biopic in the early 1950s. But Groucho was all in favour and Wilder and Diamond produced a 40-page treatment that saw the zany trio steal attaché cases of diamonds from Tiffany's only to be mistaken for the Latvian delegation to the UN while trying to make their getaway. One can only muse on the madcap antics that might have followed. But A Day At the United Nations was shelved after Harpo suffered a heart attack while rehearsing for a TV special and it was abandoned altogether after Chico died in October 1961.

Never one to let the grass grow, Wilder teamed up with another 1930s veteran to make One, Two, Three (1961), whose rat-a-tat dialogue was perfectly suited to James Cagney's motormouth delivery style. Created by merging a Ferenc Molnár play with the core concept of Ninotchka, this pugnacious satire was set in West Berlin and focused on the efforts of Coca-Cola executive CR MacNamara to recover his teenage daughter, Scarlett (Pamela Tiffin), after she elopes with left-leaning agitator Otto Piffl (Horst Buchholz). However, the film seemed less amusing to Cold War audience once the Berlin Wall was erected and it's only in the post-Soviet era that Wider and Diamond's gags about Iron Curtain paranoia and Coca-Cola colonialism have been fully appreciated.

Deciding to let Realpolitik take a backseat, Wilder optioned Marguerite Monnot and Alexandre Breffort's hit stage musical, Irma la Douce (1963), in order to reunite Jack Lemmon and Shirley MacLaine in a moral comedy of errors that delights in pushing the envelope. Having been fired from the Parisian police force for raiding a bordello under the protection of his boss, Nestor Patou begins pimping for prostitute, Irma la Douce. He becomes so besotted with her, however, that he poses as Lord X in order to become her sole client.

MacLaine was nominated for her work, while Andre Previn won the Oscar for Best Score. But the media response was muted and Wilder suffered another setback when Kiss Me, Stupid (1964) was released to mixed reviews after a complex gestation. Reworking The Dazzling Hour, the Anna Bonacci play, the project had been planned as a vehicle for Jack Lemmon and Marilyn Monroe. Following the latter's death in August 1962, however, the picture had to be recast.

Pregnancy caused Jayne Mansfield to drop out and Kim Novak emerged from a two-year absence to co-star with Peter Sellers. However, he was forced to withdraw after suffering 13 heart attacks and Dean Martin took over the role of Dino, the hard-drinking singer whose car breaks down in Climax, Nevada, where his reputation as a ladies' man prompts amateur songwriter Orville J. Spooner (Ray Walston) to hire waitress Polly the Pistol (Novak) to pose as his wife in the hope she can seduce Dino into buying some of Spooner's tunes.

While the script's winking bawdiness was frowned upon in some quarters, the Catholic Legion of Decency was so appalled by the attitude to adultery that it condemned the picture and ordered the faithful not to see it. This was the first film to receive this sanction since Elia Kazan's Baby Doll (1956), but Wilder wore it like a badge of honour, as he proceeded to present an even more jaundiced view of American life in The Fortune Cookie (1966), which earned Walter Matthau the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor in the first of his 10 collaborations with Jack Lemmon.

Returning to the theme of insurance that had informed Double Indemnity and The Apartment, the story centres on a scheme by shyster lawyer William H. Gingrich (Matthau) to wring a bumper payment out of the Cleveland Browns American Football team after his sports cameraman brother-in-law Harry Hinkle (Lemmon) is involved in a minor collision with star player, Luther 'Boom Boom' Jackson (Ron Rich). In fact, Wilder had considered Frank Sinatra and Jackie Gleason for the role of 'Whiplash Willie', but Lemmon had insisted on Matthau and persuaded Wilder to shut down production to give him time to recover from a heart attack.

By the time they rejoined Wilder for The Front Page (1974) and Buddy Buddy (1981), Lemmon and Matthau had worked together on Gene Saks's The Odd Couple (1968) and Lemmon's directorial bow, Kotch (1971). However, neither of the later Wilder teamngs is currently available on disc. But it is possible to enjoy Lemmon on Golden Globe-winning form opposite Juliet Mills in Avanti! (1972), an adaptation of a Samuel Taylor play that sees Baltimore businessman Wendell Armbruster, Jr. arrive on the Italian island of Ischia to discover that his revered father had been conducting a decade-long clandestine affair with the mother of London shopgirl, Pamela Piggott.

In 1968, the Production Code that Wilder had long sought to circumvent was replaced by a new ratings system. But, with the studio system in disarray, Wilder was preoccupied with his most expensive project (at $10 million), The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970). Originally intended to be a musical with songs by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe, the 165-minute extravaganza was to have starred Peter O'Toole and Peter Sellers as Holmes and Dr Watson. But the former priced himself out of the role, while the latter walked away after Wilder dubbed him an 'unprofessional rat fink' around the time he had contributed a few uncredited scenes to the 1967 James Bond parody, Casino Royale.

Wilder replaced them with Robert Stephens and Colin Blakely and ditched the song score. But misfortune blighted a Scottish shoot that culminated in the mechanical monster created by Wally Veevers sinking to the bottom of Loch Ness. Slow progress on the edit meant that Wilder had to leave to make Avanti! and he returned to discover that United Artists had taken the decision to remove flashbacks set in London and Oxford, as well as two subplots involving 'Naked Honeymooners' and an 'Upside Down Room'.

As a director who had always plumped for a functional visual style to allow the audience to focus on the characters and the dialogue, Wilder felt betrayed that the heart had been ripped out of his film. He was later dismayed to discover that the excised scenes had been destroyed and that he couldn't fashion a 'director's cut'. Ranked by some as one of the finest Hollywood films of the 1970s, this revisionist take on 221B Baker Street has since been cited as an influence by Mark Gatiss and Stephen Moffat on their award-winning BBC series, Sherlock (2010-17).

By the end of the decade, Wilder's brand of cinema had begun to seem old-fashioned. In adapting Tom Tryon's novella, Fedora (1978), he invoked the spirit of Joe Gillis in casting William Holden as Barry 'Dutch' Detweiler, whose hopes of coaxing the reclusive Fedora (Marthe Keller) out of retirement to star in a new version of Anna Karenina are thwarted by a mystery involving Fedora's daughter and Countess Sobryanski (Hildegard Knef), a Polish migrant with an age-defying secret to protect. Wilder had been keen to team Marlene Dietrich and Faye Dunaway, but the former loathed Tryon's story and Wilder struggled to find an audience for the film after Allied Artists withdrew from a distribution deal following some disappointing test screenings.

Three years later, Wilder found himself in reluctant retirement, as Hollywood turned its back on him. He was feted with such baubles as the American Film Institute Life Achievement Award and the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award, while admiring articles were written about his collection of modern art. But he would have sold any number of masterpieces in order to make one more movie.

His hopes of filming Schindler's List were dashed by Spielberg in 1993 and Wilder remained a frustrated figure in his luxurious apartment on Wilshire Boulevard until he succumbed to pneumonia at the age of 95 on 27 March 2002. Quoting the last line of Some Like It Hot, Le Monde headlined its front-page obituary, 'Billy Wilder dies. Nobody's perfect.' One tribute claimed he was 'smart, funny, wicked, dirty, urbane, naughty'. But, more importantly, Wilder was unique.

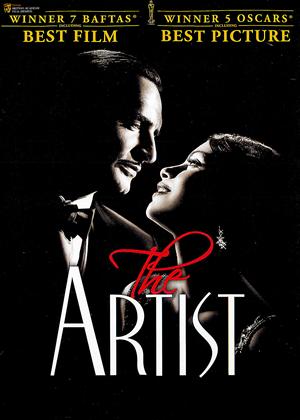

When Michel Hazanavicius won the Oscar for Best Director for The Artist (2011), his acceptance speech contained the memorable line, 'I would like to thank the following three people, I would like to thank Billy Wilder, I would like to thank Billy Wilder, and I would like to thank Billy Wilder.' However, Fernando Trueba had beaten him to the gag. On accepting the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film for Belle Époque (1992), the Spaniard has stated, 'I would like to believe in God in order to thank him. But I just believe in Billy Wilder. So, thank you, Mr Wilder.' The following day, Trueba received a phone call that began with the Austrian-accented greeting, 'Fernando, it's God.'

We hope you enjoyed our overview of the one and only Billy Wilder. Who would you like to meet next in our 'Instant Expert's Guide' series? Tell us on any of our social media channels!