With May December coming to high-quality DVD and Blu-ray, Cinema Paradiso adds Todd Haynes to its popular Instant Expert series about the finest film-makers in screen history.

Although he may not be particularly prolific, Todd Haynes has consistently demonstrated cinema's potential to reinvent itself. His approach may be less confrontational than it once was, but it remains experimental, as he seeks new ways to subvert generic and stylistic convention. Favouring formalism over realism, he often exploits the artifice of cinema to expose flaws in society and its conformist codes of morality.

Film is not just a creative process for Haynes, however. He also sees it as a means of social and personal expression that enables him to explore themes of identity and sexuality, with an emphasis on outsiders who have to challenge prevailing attitudes and power structures in order to live and love on their own terms. This explains why a number of Haynes's films have focussed on artists (primarily musicians), as they frequently have to position themselves as outliers in order to secure the freedom they need to innovate, incite, and inspire.

Supercalifragilisticexpialitoddcious

Todd Haynes was born in Los Angeles on 2 January 1961. Parents Allen and Sherry had met as summer camp counsellors and married at 19. Allen was in the military when his son was born, but he eventually became a rep for a cosmetics company. Before becoming a homemaker, Sherry had studied acting with Salome Jens at the Stella Adler Studio. Her Jewish father, Arnold Semler, had risen through the ranks at Warner Bros from messenger boy to head of set construction. As a union organiser, he had known many of those blacklisted during the postwar Communist witch-hunt conducted by the House UnAmerican Activities Committee and left Hollywood to set up his own radio communications business.

Raised in Encino in the San Fernando Valley, Todd was encouraged from an early age to express himself artistically and always had a sketch pad with him. At the age of three, he saw Robert Stevenson's Disney classic, Mary Poppins (1964), which he later claimed had sent him into 'a total imaginative rapture', as he underwent 'a fanatical, creative, obsessional response where I had to replicate the experience'. Alongside Julie Andrews in his pantheon of adored influences were Lucille Ball and Elizabeth Montgomery, who played witch Samantha Stephens in Bewitched (1964-72). However, while she was prepared to dress up as Mary Poppins while pregnant with his sister, Sherry was concerned by the fact that he only drew women.

Wendy became Todd's playmate until brother Shawn came along in 1971, when the children moved into a new house that their parents had built themselves. As Todd later recalled, he and Wendy 'would do little shows for each other under her bedroom table with a blanket on top and a desk lamp for the light source. Mine always would be really sad stories about girls and their horses and the horse would die and come back to life and she'd cry.'

Bompi and Monna (as Haynes called grandparents Arnold and Blessing) encouraged such creativity. A painter who had studied the harp and piano, Blessing was among the first to seek what her grandson called the 'Californian quest for spiritual meaning and psychic growth'. Monna and Bompi also treated him to films, plays, concerts, and exhibitions in Los Angeles. When he was nine, they took him to New York City and Washington, D.C. before accompanying him on a trip to the Far East when he was 14.

Upset by his parents arguing, Haynes sought sanctuary in creativity. When he appeared on The Art Linklater Show in 1968, he responded to a question about what he wanted to be when he grew up by proclaiming, 'An actor and an artist.' He took his first steps later that year, when he was so bowled over by Franco Zeffirelli's Romeo and Juliet that he made his own 15-minute version on a Super-8 camera. 'I made the tunics out of towels,' he recalled, 'tied a rope around the middle, got tights. My dad would run the camera, and hold the sword offscreen when I was playing Mercutio. And then we'd do the other side and I'd dress in Tybalt's outfit.' By now a veteran of numerous 'after dinner' presentations, six year-old Wendy played the Nurse and she thinks back on the project with affection. 'Who was this creature?' she had wondered about her brother. 'What's going on in there? It wasn't stopping. It was a train. It left the station when he was born. It's a beautiful thing to see someone who knows his destiny.'

Such was his determination to make the most of his talents that Haynes spent a decade's worth of weekends at Virginia Rothman's Art School in Studio City. Here, he drew a picture of singer Diana Ross with six arms, which he managed to deliver in person at the Universal Amphitheatre. He similarly showed up at Joni Mitchell's house with some illustrations of her lyrics. As school friend and future actress, Elizabeth McGovern, revealed, he was very put out that she never wrote to thank him.

Oakwood School in North Hollywood was renowned for being progressive and Haynes cut a distinctive figure with his long blonde hair. Inseparable from McGovern, they acted in school plays together and spent hours rehearsing scenes or improvising scenarios. 'He was a work machine,' McGovern reflected. 'You'd never see Todd just hanging out. If he was sitting down, he was drawing or writing. Seven days a week. Every waking hour he was making something.'

A ninth-grade writing assignment on heroes led to Haynes making a 22-minute Super-8 short entitled, The Suicide (1978). 'I always felt identification with the outcast, fragile, vulnerable people in the classroom,' he said years later. 'I had an empathy for kids who had a harder time fitting in.' In the film, Lenny (David Blaikie) is bullied at junior high and becomes so scared of leaving for high school that he attacks himself with scissors in a pristine white bathroom. While Haynes was happy with the sophisticated montage structure, he was less pleased with the sound and was able to wangle a session on a soundstage at the Samuel Goldwyn Studio, where Martin Scorsese had been mixing his documentary on The Band, The Last Waltz.

'We brought our little Super-8 projector,' Haynes recalled, 'and synched up to a mixing board, with all our tracks of 35-mm sound, the music, the effects, the dialogue. We did it in a real way. It was crazy.' He even booked a cinema in Westwood for the premiere. One parent ordered a limo for the occasion, but Haynes didn't enjoy the ersatz Hollywood glitz. 'I kind of turned against that in my head,' he mused. 'I said, "I don't want to replicate that system. I want to make experimental films, and I want to do them alone."'

In an interview after he had become an established director, Haynes reconsidered his teenage self. 'I know that I enjoyed being seen,' he said, 'performing and putting on shows for the family, impressing people with my drawings and paintings. But there may have been something beyond that, where what I was really interested in was replaying my own pleasure in seeing: returning to that moment of seeing Mary Poppins on film, seeing Romeo and Juliet. The rapture was in the process of re-creating it, over and over. I remember feeling stimulated through my entire body. I would walk around looking at the world literally through frames.'

Among the other films to shape this sensibility were Arthur Penn's The Miracle Worker (1962), Mike Nichols's The Graduate (1967), and Charles Jarrott's Anne of the Thousand Days (1969). But Haynes also took heed of the advice given to him by his 11th grade film teacher, Chris Adam, who opined that 'films were not about reality'. While an image might look authentic, it had been consciously composed rather than left to chance. Inspired by this revelation, Haynes began to question cinema's preoccupation with capturing reality. 'It started to make me think,' he recalled, 'about stylistic and formal changes and deviations.' The signs were all there.

Three Short Steps

Before heading to university, Haynes decided to take a gap year. He spent several months backpacking in Europe before joining the uncles opening a restaurant on the Hawaiian island of Kauai. Living alone in a shack, he painted and tackled some of the books on his college reading list. Having revelled in this 'little moment of really rich self-education, of creative and intellectual immersion', Haynes set off to Brown University to study art, literature, and semiotics. His course 'combined Freud, Marx, and feminism' and left him with 'a strong interest in popular form, combined with a strong desire to invert it'.

After taking a year's break because he felt he was settling into a routine that was dulling his appreciation of the course, Haynes returned to complete his degree. His graduation project was Assassins: A Film Concerning Rimbaud (1985), an amalgam of episodes from the lives of French poets Arthur Rimbaud and Paul Verlaine and self-reflexive scenes from the making of the film that was set to a soundtrack that included Throbbing Gristle and Iggy Pop. Dubbed by one critic, 'a rambunctious mashup of artifice and anachronism', the 43-minute film ended with Haynes himself reading the anti-bourgeois last line of Rimbaud's 'Morning of Drunkenness', which he later joked gave notice that he 'was never going to crawl into the Hollywood world of feature filmmaking'.

Haynes also came out at college and was surprised by the fact that his father took the news better than his mother. She eventually came round, but Haynes became closer to his father during his twenties, after he spent a month sleeping on the floor of his hospital room after Allen had suffered a near-fatal aortic rupture.

While at Brown, Haynes met Christine Vachon, who would go on to produce all of his features in becoming one of the most significant figures in New Queer Cinema. He followed her to New York, where she was working for a cable film network. During his stint as a gallery preparator in SoHo, Haynes became involved in ACT UP, the AIDS awareness movement whose work is recalled in David France's documentary, How to Survive a Plague (2012). As part of the Gran Fury art collective, Haynes contributed to a New Museum exhibition and he would return to the crisis in his first two features.

Keen to make films on his own terms, Haynes joined forces with Vachon and their Brown friend Barry Ellsworth to form Apparatus Productions, which elicited grants from the National Endowment For the Arts and the New York State Council For the Arts in order to make 'experimental narrative' films. The first was produced over 10 days while Haynes was taking a Master of Fine Arts course at Baird College.

Infamously making use of Barbie dolls, Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story (1987) revisited the life of the singer who had died at the age of 32 of heart failure brought on by anorexia. Vachon later recalled the premiere screening. 'When it began,' she wrote, 'there were gasps and laughter from the audience, because it was so funny and perfect to have Karen Carpenter played by a Barbie doll. But at the end, when the doll turned around and half her face was gone, carved away by weight loss, it wasn't so funny anymore, and some people burst into tears.'

Shockingly skeletonising the doll with a blade, the film aimed criticisms at Karen's parents, as well as Richard, her brother and partner in The Carpenters. He sued for copyright infringement because Haynes and co-writer/producer Cynthia Schneider had failed to licence the songs used on the soundtrack. In 1990, the verdict resulted in the 43-minute film being removed from public distribution, although pirated copies soon went into circulation and the still-outlawed film can readily be found online.

Getting Haynes known at the 1988 Toronto International Film Festival, Superstar brought an offer to direct the music video for Sonic Youth's 'Disappearer'. This can be rented from Cinema Paradiso on Corporate Ghost (2004), while more can be learned about Kim Gordon, Thurston Moore, and Lee Ranaldo in David Markey's 1991: The Year Punk Broke (1992). By this time, Haynes had already made his feature bow. But he return to the shorter form one more time.

Allen Haynes had always joked that his son's artistic precociousness had made him something of a 'child of God' and Haynes revisited this aspect of his childhood in Dottie Gets Spanked (1993), which was made for the PBS TV series, Families.

Living with his parents in 1960s suburbia, six year-old Steven Gale (J. Evan Bonifant) spends his time drawing in front of the television while watching favourite programmes like The Dottie Show. A neighbour comments on his infatuation with Dottie Frank (Julie Halston) and its significance dawns on the boy's father when he sees a lovingly coloured drawing of Dottie being spanked.

Running 30 minutes, the story was inspired by Haynes's boyhood obsession with the sitcoms, I Love Lucy (1951-57), The Lucy Show (1962-68), and Here's Lucy (1968-74), which reached new heights after Bompi used his contacts to get his seven year-old grandson into the Paramount Television studio to watch idol Lucille Ball rehearse. As Haynes told the New Yorker, 'I could feel my parents behind me, worrying about what this might mean, or worrying whether they should be worried, and I always felt defiant of their concerns.' But this is an affectionate paean of gratitude to film and television for the way in which they guide young minds through the emotional and sexual minefields that are experienced at an age when kids don't feel they can ask a grown-up for answers. Perhaps that's why Steven wears red shoes like those worn by Dorothy Gale (Judy Garland) in another treatise on becoming one's true self, Victor Fleming's The Wizard of Oz (1939).

Getting Allegorical

Three novels by Jean Genet inspired Haynes's debut feature, Poison (1991). The writer had himself directed a gay cinematic landmark with Un chant d'amour (1950), while Joseph Strick's The Balcony (1963), Tony Richardson's Mademoiselle (1966), Christopher Miles's The Maids (1974), and Rainer Werner Fassbinder's Querelle (1982) were all based on Genet texts and can be rented on disc from Cinema Paradiso.

Haynes intercut the storylines of Our Lady of the Flowers (1943), Miracle of the Rose (1946), and Thief's Journal (1949) to create three vignettes that he filmed in a different style. Showing how an abused seven year-old shoots his father, 'Hero' borrowed the tropes of a TV news magazine show, while 'Horror' paid homage to trippy 60s B movies to record the effects on a scientist of the elixir of human sexuality. Finally, 'Homo' mixed romantic fantasy and prison movie grit, as two borstal friends meet up again in jail.

Having taken the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance, Poison won the Teddy Award at the Berlin Film Festival. Yet, despite some enthusiastic reviews, it only received a limited release in the United States, where the Reverend Donald Wildmon, of the American Family Association, denounced the National Endowment For the Arts for investing $25,000 in a picture containing scenes of graphic gay sex. If he had bothered to watch the film, of course, Wildmon would have known that actors Scott Renderer and James Lyons (who was Haynes's partner and co-editor) indulged in no such activity.

By contrast, cult director John Waters said of Haynes, 'He has restored my faith in youth,' while The Washington Times declared him, 'the Fellini of fellatio'. Moreover, critic B. Ruby Rich listed Poison among the defining films of 'New Queer Cinema', alongside Jennie Livingston's Paris Is Burning (1990), Isaac Julien's Young Soul Rebels, Christopher Munch's The Hours and Times (both 1991), Tom Kalin's Swoon, and Gregg Araki's The Living End (both 1992). As Haynes later reflected: 'The thing I dug about New Queer Cinema was being associated with films that were challenging narrative form and style as much as content. It wasn't enough to replace the boy-meets-girl-loses-girl-then-gets-girl with a boy-meets-boy version. The target was the affirmative form itself, which rewards an audience's expectations by telling us things work out in the end. Queerness was, by definition, a critique of mainstream culture. It wasn't just a plea for a place at the table. It called into question the table itself.'

What pleased Haynes most, however, was that his success enabled him to sign a cheque for $184,000 to pay back the money that Bompi had loaned him. Yet, despite suddenly having a national platform, which he used to raise AIDS awareness, Haynes struggled to raise funding for a follow-up feature. Four years passed before he secured the $1 million he needed to make Safe (1995), which marked the beginning of his ongoing partnership with Julianne Moore. In her first feature lead, she excels as Carole White, a San Fernando Valley housewife whose life with husband Greg (Xavier Berkeley) seems idyllic until she starts feeling unwell. With the doctors unable to find any reason for her sudden adverse reaction to her surroundings, Carol checks into Wrenwood, a New Mexican facility run by New Age guru, Peter Dunning (Peter Friedman), for those suffering from environmental ailments.

Based on extensive research to ensure the allegorical references to AIDS were rooted in sound science and socio-psychological theory, the action subverted the conventions of those 'Disease of the Week' teleplays that were so prominent at the time. However, Haynes avoided any explanations or resolutions. 'I was coy, I was tricky,' he divulged. 'I wanted to touch that little bit in everyone where you just aren't convinced that who you think you are is really who you are - that moment when you feel like a forgery.'

Haynes sought inspiration from Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Chantal Akerman's Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), and Randal Kleiser's The Boy in the Plastic Bubble (1976), while the visual style took its cues from Michelangelo Antonioni's Red Desert (1964). There are also echoes of Bryan Forbes's adaptation of Ira Levin's The Stepford Wives (1975) in the way in which Haynes slips horror into the rubric of 'the woman's picture'. He and Moore were nominated at the Independent Spirit Awards, while Safe was voted the Best Film of the Decade by critics at The Village Voice.

A Touch of the Musicals

Music plays a key role in Haynes's work, with the soundtrack to his youth having a particularly special place. Having sparked controversy in retelling the story of The Carpenters, he decided to play slightly safer in recalling the era of Glam Rock in Velvet Goldmine (1998), which was co-produced by Christine Vachon and REM frontman, Michael Stipe.

Although it took its title from a David Bowie track, he refused permission to use his songs and Haynes had to use cuts by Brian Eno, Marc Bolan, and Steve Harley to complement the various cover versions and originals played by two ad hoc bands, The Venus in Furs - who included Radiohead's Thom Yorke and Jonny Greenwood, Suede's Bernard Butler, and Roxy Music's Andy Mackay - and Wylde Ratttz, whose line-up included Thurston Moore and Ron Asheton from The Stooges.

Adopting the flashback structure used by Orson Welles in Citizen Kane (1941), Haynes followed British journalist Arthur Stuart (Christian Bale) in his bid to track down Brian Slade (Jonathan Rhys-Meyers), the androgynous Glam icon who had vanished after abandoning his Maxwell Demon persona. Among those he interviews are Slade's wife, Mandy (Toni Collette), and his manager, Jerry Devine (Eddie Izzard), as well as rock provocateur, Curt Wild (Ewan McGregor).

While Wild contained elements of Lou Reed and Iggy Pop, Slade was an amalgam of Bowie, Bolan, Bryan Ferry, and Jobriath, who had been one of first famous musicians to die of AIDS. The virus once again plays a significant role in the action, which also riffs on motifs from the work of Oscar Wilde, Jean Genet, and George Orwell in exploring notions of identity, sexuality, self-expression, excess, and the pressure fans place upon their idols.

In addition to winning a prize for Best Artistic Contribution from the Special Jury at Cannes, the picture also went on to earn Sandy Powell an Oscar nomination for Best Costume, as she had the rare distinction of beating herself to the award for her work on John Madden's Shakespeare in Love (1998). The reviews were mixed, however, and, even though it amassed a respectable $4,313,644 worldwide, Velvet Goldmine felt much more conventional than Superstar, despite the inclusion of a love scene in which Slade and Wild are played by dolls.

Co-scripted by Oren Moverman, Haynes's next musical excursion was markedly bolder, as six different performers took the lead in I'm Not There (2007), which was 'inspired by the music and the many lives of Bob Dylan'. In fact, Dylan isn't mentioned at all during the film and it's apt that the title came from a track from the famous Basement Tapes bootleg that received its first official release on the soundtrack album.

Each manifestation represents a part of Dylan's shape-shifting past. His poetic nature is embodied by Arthur Rimbaud (Ben Whishaw), while his troubadour side is embodied by Woody Guthrie (Marcus Carl Franklin). Capturing the essence of the folkie who is born again requires Christian Bale to essay both Jack Rollins in the early 1960s and Pastor John in the mid-1970s, while there also a degree of duality as Heath Ledger essays Robbie Clark, an actor who becomes famous for depicting Rollins in the biopic, Grain of Sand. Echoes of D.A. Pennebaker's Don't Look Back (1967) reverberate around the next section, as acoustic singer Jude Quinn (Cate Blanchett) is accused of selling out by going electric, while Richard Gere steps into the shoes of outlaw Billy McCarty in a Wild West segment that limns Sam Peckinpah's Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973).

A Charlie Chaplin storyline was cut during pre-production, but there is plenty here to keep Dylan fans guessing and engrossed, as Haynes flits between biography and fantasy, within a framework of historical fact and enduring enigma. The reviews were more admiring than awed, which rather summed up Dylan's response in Rolling Stone: 'Yeah, I thought it was all right. Do you think that the director was worried that people would understand it or not? I don't think he cared one bit. I just think he wanted to make a good movie. I thought it looked good, and those actors were incredible.'

Haynes won the Grand Jury Prize at the Venice Film Festival, where Blanchett received the Volpi Cup to go with her Oscar and BAFTA nominations for Best Supporting Actress and her triumph in the same category at the Golden Globes. Some years later, Haynes contributed a section on the Follies song, 'I'm Still Here', to the HBO documentary, Six By Sondheim (2013), while he ventured into actuality for the first time with The Velvet Underground (2021), which recalled how Lou Reed, Sterling Morrison, John Cale, Doug Yule, and Maureen Tucker formed an avant-garde band under the management of artist Andy Warhol, who persuaded them to collaborate with Nico, the German model/actress/singer, who had appeared in The Chelsea Girls (1966).

Haynes also inherited Fever, a biopic of singer Peggy Lee that had been scripted by Nora Ephron before her death in 2012. Reese Witherspoon had been slated to star, but she opted for a producing berth, as Michelle Williams took on the lead. But, while the project was shelved during the pandemic, it's remains in the pipeline, with Billie Eilish being linked to an executive producing role. As Haynes explained at the 2023 New York Film Festival, 'the interest in the subject hasn't gone away. The amazement with the subject and her art hasn't gone away. And the desire to work with Michelle again hasn't gone away.' So, who knows when the fates and the schedules will next be in alignment...

Haynespiration

As he consistently reveals in interviews, Haynes is a keen student of cinema and his work is studded with references to his favourite films. Cinema Paradiso members have more access to these pictures than customers of online streaming platforms, who can't hope to compete with the 100,000 titles available to order from our website with just a single click.

Harking back to the Golden Age of Hollywood, Haynes has name-checked Frank Capra's Meet John Doe (1941), a socio-political underdog drama that brought Gary Cooper together with Barbara Stanwyck (after Ann Sheridan and Olivia De Havilland had turned down the role), and Irving Rapper's Now, Voyager (1942), which became famous for the scene in which Paul Henreid simultaneously lights cigarettes for himself and Bette Davis. After a detour to Britain for housewife Celia Johnson to have qualms about an affair with doctor Trevor Howard in David Lean's Brief Encounter (1945), Haynes takes us back to the studio heyday, where Bette Davis and Gloria Swanson respectively excel as divas Margot Channing and Norma Desmond in Joseph L. Mankiewicz's All About Eve and Billy Wilder's Sunset Boulevard (both 1950), which racked up 22 Oscar nominations between them.

Staying in 1950, Haynes has expressed his admiration for Nicholas Ray's brooding noir, In a Lonely Place, in which Gloria Grahame can't bring herself to believe that troubled screenwriter Humphrey Bogart is a murderer. Socialite Elizabeth Taylor similarly has implicit faith in Montgomery Clift, in spite of the death of factory girl Shelley Winters in A Place in the Sun (1951), George Stevens's adaptation of Theodore Dreiser's acclaimed novel, An American Tragedy.

Following the death of mother Shelley Winters (she did have it tough in the movies), siblings Billy Chapin and Sally Jane Bruce find themselves imperilled by bogus preacher, Robert Mitchum, in Charles Laughton's The Night of the Hunter (1955). This was the actor's sole outing behind the camera, but German émigré Douglas Sirk made a number of deceptively glossy melodramas around the same time that had a considerable impact on film-makers like Haynes, who (as we shall see) referenced the likes of All That Heaven Allows (1955) and Written on the Wind (1956) in the two dramas he set in the 1950s.

Another exile (this time from HUAC), Joseph Losey also captured Haynes's imagination, notably with two studies of class division, as the downstairs duo of Dirk Bogarde and Sarah Miles make life difficult for James Fox and Wendy Craig in The Servant (1963) and unsuspecting 12 year-old Dominic Guard passes messages between his friend's older sister (Julie Christie) and a tenant farmer (Alan Bates) during a summer stay in Norfolk in the Palme d'or-winning adaptation of H.E. Bates's The Go-Between (1971).

Three pictures by Ingmar Bergman have recurred in Haynes's discussions of his own career. Cinema Paradiso can offer the monochrome duo of Winter Light (1963) and Persona (1966), but Face to Face (1976) is currently unavailable. We can also bring you Jean-Luc Godard's seventh feature, Masculin Féminin (1966), a snapshot of mid-60s French society that uses its 15 vignettes to contextualise the hesitant romance between demobbed soldier Jean-Paul Léaud and aspiring pop singer, Chantel Goya.

Another amour fou dominates Mike Nichols's The Graduate (1967), as twentysomething Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman) realises he's falling for Elaine (Katharine Ross), the daughter of Mrs Robinson (Anne Bancroft), the family friend with whom his having an illicit affair. A very different image of post-Camelot America dominates Russ Meyer's Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970), a parody of Mark Robson's adaptation of Jacqueline Susann's Valley of the Dolls (1967) that was co-scripted by maverick director Meyer and revered film critic, Roger Ebert.

The flipside of fame also comes under scrutiny in Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg's Performance (1970), as London gangster, Chas (James Fox), comes to regret seeking sanctuary in the home of decadent rock star, Turner (Mick Jagger). Haynes also admired Roeg's Bad Timing (1980), which sees Inspector Netusil (Harvey Keitel) investigating the relationship between American suicide, Milena Flaherty (Theresa Russell), and Vienna-based psychoanalyst, Alex Linden (Art Garfunkel).

These films are replete with the images and ideas that have abounded in Haynes's own films and the same is true of John Schlesinger's Sunday Bloody Sunday (1971), in which divorced consultant Glenda Jackson and gay Jewish doctor Peter Finch compete for the attention of bisexual artist, Murray Head. This pioneering study of sexual preference caused ripples on its release. But no director of this period addressed LGBTQIA+ issues with such raw courage and ferocity than Rainer Werner Fassbinder, whose Fear Eats the Soul (1974), The Marriage of Maria Braun (1978), Lola (1981), and Veronika Voss (1982) have all impacted upon Haynes's work.

It's the timing of the editing to complement the dialogue and the performances that most impressed Haynes about Woody Allen's Manhattan (1979), while the discretion of the direction was singled out among the reasons for his admiration for two coming out sagas, Gus Van Sant's My Own Private Idaho (1991) and Terence Davies's The Long Day Closes (1992), and for Claire Denis's Beau Travail (1999), a reworking of Herman Melville's novella, Billy Budd, that is set on a French Foreign Legion base in Djibouti and follows the irrational efforts of Adjudant-Chef Galoup (Denis Lavant) to destroy rookie legionnaire, Gilles Sentain (Grégoire Colin).

Sirk du Soleil

We have already mentioned the influence that Douglas Sirk exerted on Todd Haynes's oeuvre. But it's particularly strong in a pair of drama set in the 1950s, with All That Heaven Allows, Written on the Wind, and Imitation of Life (1959) underpinning the discussion of class, sexuality, gender status, and race in Far From Heaven (2002).

Julianne Moore was always going to play Cathy Whittaker, the housewife from Hartford, Connecticut who divorces after discovering that her husband is gay. Haynes wanted to cast James Gandolfini as Frank, but he was busy with The Sopranos (1999-2007) and Dennis Quaid was hired after Jeff Bridges demanded too much money and Russell Crowe complained that the role was too small. Dennis Haysbert was cast as Raymond Deagan, the son of Carol's recently deceased Black gardener, while Viola Davis took on the role of Sybil, the housekeeper who is not afraid to speak her mind to her supposed betters.

The Production Code had prevented Sirk from exploring topics like homosexuality and the anti-miscegenation laws that would remain in force in the United States until 1967. But, while Haynes had no such restrictions, he approached Frank's secret and Carol's growing attraction to Raymond with 1957-like discretion. While the dialogue was circumspect, however, Haynes had production designer Mark Friedberg and costumier Sandy Powell use colours to code the characters according to their race and class. Cinematographer Edward Lachman used light, angles, and camera movements to reinforce these strata, while the emotional tone of the drama was counterpointed by an Elmer Bernstein score that owed much to the melodies and arrangements of the Eisenhower era.

There was no postmodernist irony in Haynes's recreation of the Sirkian mise-en-scene, although there are nods towards Fassbinder's Fear Eats the Soul in the way Carol and Raymond are treated when their romance becomes public. Hence the absence of a happy ending that had been de rigueur with so-called 'weepies' in postwar Hollywood. As Haynes explained in an interview: 'From the outset, I think it was about embracing this beautiful, almost naïve language of words, gestures, movements, and interactions that were totally prescribed and extremely limited - not condescending to it, but allowing its simplicity to touch other feelings that you can't be over-explicating.'

Premiering at Venice, Far From Heaven was beaten to the Golden Lion by Peter Mullan's The Magdalene Sisters. But Moore won the Volpi Cup for Best Actress, while Lachman's photography earned him a prize for Outstanding Individual Contribution. Moore was nominated at the Golden Globes, BAFTAs, and Oscars, only to lose at the latter ceremony to Nicole Kidman for Stephen Daldry's The Hours. Haynes missed out on Best Original Screenplay to Pedro Almodóvar for Talk to Her, while Bernstein and Lachman were pipped by Elliot Goldenthal for Julie Taymor's Frida and the late Conrad Hall for Sam Mendes's Road to Perdition (all 2002). Nevertheless, Haynes's best work to date drew positive reviews and made $29 million on its $13.5 million budget.

Around this time, Haynes left New York to set up home in Portland, Oregon. Sister Wendy - who was now the lead singer of the glam rock band, Sophe Lux & the Mystic - had already settled here, as had Haynes's director friend, Kelly Reichardt. Wendy had reassured him that this was a city in which 'everybody gets to let their freak fly' and the re-energised Haynes wrote Far From Heaven and started work on I'm Not There in a burst of creativity. Moreover, he met aspiring writer Bryan O'Keefe at an Oscar party and they moved into an Arts and Crafts cottage in 2005, with furniture salvaged from the set of Far From Heaven.

Perhaps the period vibe shaped Haynes's thinking, as he returned to the 1950s while preparing the Image Book for his next picture, Carol (2015). Filled with sketches, shot lists, and editing notes that are vital to what Haynes calls his 'psychic process', these mini-magazines are distributed to the production department heads on each film to ensure that everyone film is on the same stylistic and emotional page.

Set New York, this drama had been adapted from The Price of Salt, the semi-autobiographical novel that thriller writer Patricia Highsmith had published under the name 'Claire Morgan' in 1952. Haynes used a screenplay by Highsmith's playwright friend, Phyllis Nagy, which had previously been considered by Kenneth Branagh, Kimberly Peirce, Hettie MacDonald, John Maybury, Stephen Frears, and John Crowley. Cate Blanchett and Mia Wasikowska were linked with the project before Haynes came aboard at Christine Vachon's suggestion. But a scheduling conflict led to Rooney Mara taking over the part of Therese Belivet, an assistant at the Frankenberg's department store who helps divorcing photographer Carol Aird find a doll for her daughter in December 1952.

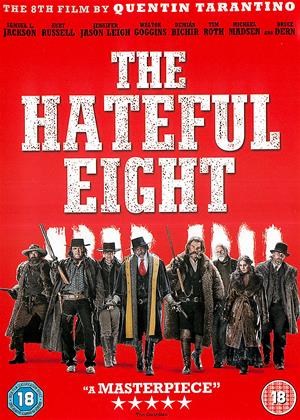

Following a 10-minute ovation after it premiered at Cannes, the film took the Queer Palm, while Mara shared Best Actress with Emmanuelle Bercot for Maïwenn's Mon Roi (2015). Mara and Blanchett competed for the acting honours at the Golden Globes, BAFTAs, and Oscars, only for Brie Larson to prevail in the Best Actress stakes in Lenny Abrahamson's Room, while Alicia Vikander took the Supporting statuette for Tom Hooper's The Danish Girl. Success also eluded Nagy, Powell, Lachman, and composer Carter Burwell, who was bested by Ennio Morricone for Quentin Tarantino's The Hateful Eight.

Haynes was overlooked for Best Director, while there was no room for Carol among the Best Picture contenders. But Haynes was content with his achievement. 'To me,' he said, 'the most amazing melodramas are the ones where, when a person makes a tiny step toward fulfilling a desire that their social role is built to discourage, they end up hurting everybody else. It's like a chess game of pain, a ricochet effect where everybody gets hurt but there's nobody to blame.' The Independent's Geoffrey McNab, concurred in recognising that, 'In sly and subversive fashion, Haynes is laying bare the tensions in a society that refuses to acknowledge "difference" of any sort.' He might not have been winning awards, but Haynes was certainly changing hearts and minds.

America's Conscience

While establishing himself as a director, Haynes produced a handful of innovative shorts, Susan Delson's Cause and Effect (1988), Mary Hestand's He Was Once (1989), and Suzan-Lori Parks's (1990). Having also worked on Brooke Dammkoehler's La Divina (1989), a New Queer classic that charts the rise of a silent icon similar to Greta Garbo, he also cropped up in front of the camera a couple of times. As well as cameoing as the phrenology head in Tom Kalin's Swoon, he also guested as himself in Michael Almereyda and Amy Hobby's At Sundance (1995), a group portrait of indie film-makers at the famous film festival that also features Robert Redford, Richard Linklater, Ethan Hawke, Gregg Araki, Abel Ferrara, Atom Egoyan, James Gray, and Haskell Wexler.

This is available from Cinema Paradiso on Almereyda's Another Girl Another Planet (1992). But we can't currently bring you Cindy Sherman's Office Killer (1997), to which Haynes contributed some uncredited dialogue or Kelly Reichardt's Ode (1999), for which he did the poster art. The latter is a close friend and Haynes has executive produced five of her features, Old Joy (2006), Wendy and Lucy (2008), Meek's Cutoff (2010), Night Moves (2013), and Certain Women (2016), as well as Richard Glatzer's Quinceañera (aka Echo Park LA, 2006) and Steven Doughton's Buoy (2012),

In 2020, Haynes returned to television for his first stab at multi-episodic drama. Joan Crawford had won the Academy Award for Best Actress for her performance in Michael Curtiz's Mildred Pierce (1945), but Kate Winslet revealed more layers of the eaterie owner who risks all to prevent her daughter, Veda, from dating ne'er-do-well, Monty Beragon. Haynes and fellow Portlander, Jon Raymond, made a fine job of teasing out James M. Cain's novel across five tension-filled parts, as Winslet battled against the wilful Evan Rachel Wood and the hissable Guy Pearce.

Winslet won a Primetime Emmy for her efforts, as Mildred Pierce (2010) converted five of its 21 nominations, with the casting, art direction, and score triumphs being topped by the win for Best Miniseries or Motion Picture Made for Television. Yet, it proved more of a critical than a viewer favourite. Touching upon many of Haynes's familiar themes, some have claimed this to be his most dramatically sustained work, which is all the more remarkable as he contracted salmonella during the shoot. As Winslet (who also won a Golden Globe) recalled, 'he just carried on working. We would do a take and he'd throw up. We would do another take, and he'd throw up again. He would sit in his chair, sweat for a bit, stand up, throw up again, and do another take. This lasted for four or five days. He was very, very unwell.'

Laura Dern also won a Golden Globe for her portrayal of self-imploding business executive Amy Jellicoe in Enlightened (2011-13), with Haynes directing her in the Season Two episode, 'All I Ever Wanted', which is available to rent from Cinema Paradiso. Two years later, Haynes was reported to be developing a series from Jodi Wille and Maria Demopoulos's HBO documentary, The Source Family (2012). But nothing about health food pioneer Jim Baker and his double life as cult leader, Father Yod, has thus far made it to the small screen. The same goes for a proposed 12-part series on Sigmund Freud.

Instead, Haynes has continued with his feature career. In 2017, he released Wonderstruck, an adaptation of a Brian Selznick novel about two deaf children seeking parents half a century apart. In the 1920s segment, Rose Mayhew (Millicent Simmonds) runs away from the New Jersey home she shares with her father in order to find her mother, the actress Lillian Mayhew (Julianne Moore). The 1970s section centres on Ben (Oakes Fegley), a Minnesota boy who sets out to find his father after he loses his mother and his hearing in a freak accident.

As ever paying attention to the visual style of the storytelling, Haynes studied the silent films of King Vidor and F.W. Murnau in order to perfect his 35mm monochrome compositions and camera movements. By contrast, he turned to grittier titles like John Schlesinger's Midnight Cowboy (1969) and William Friedkin's The French Connection (1971) to capture the cinematic and social ambience of the time. Despite taking such pains over achieving an authentic look and working through a sign language interpreter to coach the debuting Simmonds (who is deaf), Haynes was rewarded with mixed reviews and a shut-out during awards season. He remained pleased with the project, however. 'I felt like it spoke to something indomitable about the nature of kids,' he told one interviewer, 'and the ability for kids to be confronted with challenges and the unknown and to keep muscling through those challenges.'

Fortunately, the reception for Dark Waters (2019) was more enthusiastic, as Haynes took the unusual step of adapting Nathaniel Rich's New York Times Magazine article, 'The Lawyer Who Became DuPont's Worst Nightmare'. However, there was a certain Capracorniness about the 18-year fight against the odds undertaken by corporate defence attorney Robert Bilott (Mark Ruffalo), who sought to demonstrate on behalf of 70,000 residents of West Virginia and Ohio that the Parkersburg chemical plant had contaminated the water supply, spoliated farm land, harmed thousands of animals, and risked the health of the human population by knowingly dumping more than 7000 tonnes of a toxic, nonbiodegradable chemical.

Once again, Haynes did his homework and revealed that he had viewed films as different as Don Siegel's Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), Alan J. Pakula's The Parallax View (1974) and All the President's Men (1976), Mike Nichols's Silkwood (1983), and Michael Mann's The Insider (1999). Yet, despite solid reviews and a decent box-office return (as audiences do enjoy seeing behemoths being humbled), the film was again overlooked when it came to the major awards. Undeterred, Haynes accepted Best Foreign Film recognition at the Césars - where he lost out to Thomas Vinterberg's Another Round - and moved on to his first documentary feature.

Four years passed before he returned to fiction, although May December (2023) is based on the life of Mary Kay Letourneau, the 34 year-old married Seattle high school teacher who made headlines in 1996 when she had a child with 13 year-old Samoan American student, Vili Fualaau. Shortly after being released from a short prison sentence, Letourneau became pregnant again and was jailed for seven and a half years. On being freed, she fought to overturn a restraining order so that she could marry Fualaau in 2005.

Rather than simply revisit the action teleplay-style, Haynes and screenwriter Samy Burch confronted Gracie Atherton-Yoo (Julianne Moore) with actress Elizabeth Berry (Nathalie Portman), who has been cast to play her in a TV-movie about her relationship with Korean American spouse, Joe Yoo (Charles Melton). With only 23 days to shoot in Savannah, Georgia in December 2022, the production not only tested the mettle of the excellent cast, but also Haynes's ability to adapt his meticulous approach to a tight schedule. Using Ingmar Bergman's Persona and Jean-Luc Godard's Two or Three Things I Know About Her (1967) as his touchstones, Haynes also made affecting use of the score that Michel Legrand had composed for Joseph Losey's The Go-Between.

Once again, Haynes set himself the task of unsettling the complacent and forcing them to see issues from a fresh perspective. As he said in an interview, 'There's an excitement to wanting to destabilise audiences; their presumptions of what is good and evil, right and wrong. I find that to be deliciously antithetical to today's climate of how many people want representation to answer their already locked-in, hard-wired views of things.' Variety neatly summed up his achievement by opining, 'Todd Haynes unpacks America's obsession with scandal and the impossibility of ever truly knowing what motivates others in this layered look at the actor's process.'

As if to confirm that Haynes was back in the US film fraternity's good books, the film received four Golden Globe nominations, with the three acting nods being joined by a somewhat curious citation for Best Motion Picture - Musical or Comedy. At the Oscars, Burch and Alex Mechanik were nominated for Best Original Screenplay.

Never one to sit on his laurels, Haynes is currently prepping a reunion with Kate Winslet on Trust, an HBO series based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Hernan Diaz. The pitch reads: 'In a story told from multiple, competing perspectives, a 1920s Wall Street tycoon amasses a sudden fortune but loses a beloved wife. Decades later, his attempts to control the narrative of his life are undone by a biographer who uncovers the ultimate secrets of the legendary marriage.'

He is also developing a gay romantic drama that is set to star Joaquin Phoenix. As Haynes told Variety: 'It's a love story between two men set in the 30s that has explicit sexual content that or at least it challenges you with the sexual relationship between these two men. One is a Native American character and one is a corrupt cop in L.A. It's set in the 30s. They have to flee L.A. ultimately and go to Mexico. But it's a love story and with a strong sexual component. And what was so remarkable is that it all started with Joaquin having some ideas and some thoughts and just questions and images. And he came to me and said, "Does this connect to you at all?" And I was like, "Yeah, this is really interesting."

Interesting, indeed. Why not work your way through Todd Haynes's filmography, while you wait? It's what Cinema Paradiso's there for, after all. And maybe you could also try some of the pictures that have influenced him along the way!