One hundred years ago, audiences were stunned by a silent German feature that was unlike anything they had ever seen before. With its psychological complexity, painted sets and stylised acting, it was too unique to be emulated. Yet it heralded an era of Expressionist cinema whose influence can still be felt today. Indeed, few films have impacted as dramatically on the Seventh Art as Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920) and Cinema Paradiso celebrates its centenary by venturing into the long shadow cast by its legacy.

In 1920s Germany, Expressionism was in vogue across painting, literature, theatre and cinema, as it reflected the national mood following the slaughter of the Great War and the perceived humiliation of the peace terms imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. But academics can't resist a good feud and critical opinion has long been divided as to what actually constitutes a German Expressionist film.

At the heart of the debate are two books by exiled German theorists, Siegfried Kracauer's FromCaligarito Hitler (1947) and Lotte Eisner's The Haunted Screen (1952). Together, they posited a core Expressionist canon by respectively approaching cinema in the Weimar Republic from psychological and stylistic perspectives. However, the tomes also sparked controversy, with Kracauer asserting that certain films had predisposed the German population towards National Socialism and authoritarian dictatorship. The consequences are made manifest in Rüdiger Suchsland's compelling documentary, Hitler's Hollywood (2017). But our focus is on the aesthetic effect that Expressionism has had on global cinema over the last century.

Lurking in the Shadows

It's often wrongly presumed that Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr Caligari was the first Expressionist feature. In fact, shadows and angular or jagged scenery had been used to convey a sense of dislocation since Stellan Rye had filmed The Student of Prague at the Babelsberg Studios in Berlin in 1913. Making pioneering use of Guido Seeber's trick photography, this loose amalgamation of the myth of Johann Georg Faust, Edgar Allan Poe's story, 'William Wilson', and Alfred de Musser's poem, 'The December Night', had starred Paul Wegener, who would join forces with Austrian Henrik Galeen to make another proto-Expressionist landmark, The Golem (1915) which the pair would remake in 1920. Galeen would also revisit The Student of Prague in 1926, by which time German Expressionism was renowned throughout the world.

The popularity of Juan Carlos Medina's The Limehouse Golem (2016) demonstrates the continuing debt that film-makers owe to pictures produced a century ago. Yet, even before Wiene started shooting at the bijou Lixie-Atelier studio in December 1919, chiaroscuro lighting and ominous settings had become a familiar feature of the 'sensation films' produced in Denmark and Sweden by such titans of the silent era as Carl Theodor Dreyer, Mauritz Stiller and Victor Sjöström, who had a profound influence on film-makers as different as chameleonic actor Lon Chaney and Ingmar Bergman, who cast a lowering pall over such early monochrome melodramas.

Another who dabbled in dark (ish) themes when Expressionism's influence was still largely confined to literature and art was Ernst Lubitsch, whose fabled comic touch could also reveal a graver side when directing vamp star Pola Negri in the likes of The Wildcat (1919) and Sumurun (1920), which co-starred Paul Wegener and is available from Cinema Paradiso on Eureka's magnificent Lubitsch in Berlin collection. There were also flashes of sin in the so-called 'enlightenment films' that were produced to educate the masses about the less salubrious aspects of life. Following Cecil B. DeMille's patented formula of showing plenty of wickedness in lurid close-up before administering some punishment, these 'Aufklärungsfilme' aped the authenticity of the 'Strassenfilme' or 'street films', against whose gritty realism Expressionism sought to rebel.

TheCaligariEffect

Hans Janowitz and Carl Mayer were an unlikely screenwriting team. Both men were pacifists. But, while Meyer had feigned madness in order to avoid the trenches, Janowitz had served as an officer and been so appalled by what he had witnessed that he developed a lifelong mistrust of authority. Having been introduced to Mayer in Berlin, Janowitz suggested a writing partnership and, in devising The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, they had drawn on their own experiences, as well as the films of Paul Wegener, in seeking to highlight the dangers inherent in the abuse of power.

Such was the success of their sole collaboration that both Mayer and Janowitz would subsequently embellish their role in its creation. Indeed, not only did they insist that their narrative had hidden psycho-political depths, but they also swore that they had conceived the distorted visuals that would make the tale of DrCaligariso memorable. Much blame has been passed over the years about the closing coda, which the scenarists detested for corrupting their original intentions. That most unreliable of witnesses, Fritz Lang (who may have been in line to direct before he went off to make The Spiders, 1919-20) claimed to have been involved in shaping the twist (which we won't reveal here) that prompted Kracauer to accuse director Robert Wiene of having dangled the prospect of dictatorship before a populace in need of a potent leader after the disintegration of the Hohenzollern empire.

Wherever the truth lies, the scenario revolves around an extended flashback that takes place in the Gothic village of Holstenwall and centres on the impact that sideshow barker DrCaligari (Werner Krauss) and his somnambulist assistant, Cesare (Conrad Veidt) have on the lives of Francis (Friedrich Fehér) and his best friend, Alan (Hans Heinz von Twardowski), who are friendly rivals for the affections of Jane (Lil Dagover), whose father, Dr Olsen (Rudolf Lettinger), persuades the police to investigate the nocturnal prowlings of both Cesare and a knife-wielding thief (Rudolf Klein-Rogge).

Erich Pommer, the production chief at Decla-Bioscop, was persuaded to buy the screenplay and apportioned a modest budget, as German films were still being denied export licences a result of the war. Fortunately, with shortages of set-building materials and regular power cuts further hindering pre-production, producer Rudolf Meinert showed the script to production designer Hermann Warm, who began roughing out some sketches with painters Walter Reimann and Walter Röhrig, who were familiar with the Expressionist designs that director Karlheinz Martin had employed in staging the plays of Ernst Toller at Die Tribüne in Berlin. These had revolutionised Weimar theatre and Warm, Reimann and Röhrig did much the same for cinema with the canted angles, oblique lines and streaks of light and shade that they painted directly on to the backdrop in the limited shooting space that had been allocated to Wiene at Decla's studio on Franz Joseph Strasse in the north-eastern suburb of Weißensee.

The stylised acting reinforced the sense of alienation that viewers still experience on seeing this extraordinary picture for the first time. Willy Hameister's photography was relatively simple, but it captured the jagged edges of the distorted landscape and magnified the repressed desires and unconscious fears of both the characters and contemporary audience alike. No wonder leading French film-makers like Louis Delluc, Abel Gance and René Clair declared it an artistic leap forward. However. compatriots Jean Epstein and Jean Cocteau were less impressed, while Sergei Eisenstein dismissed it as 'a combination of silent hysteria, partially coloured canvases, daubed flats, painted faces, and the unnatural broken gestures'.

Despite times being hard (as Rainer Werner Fassbinder later revealed in Berlin Alexanderplatz, 1980) and the content being flagged up as highbrow, Germans flocked to seeCaligariwhen it opened in February 1920. Such was its impact in France that the term 'caligarism' was coined to denote features whose psychological complexity matched the stylised mise-en-scène, while Hollywood quickly assimilated its themes and techniques after the picture crossed the Atlantic in March 1921. But, while Wiene went on to make such interesting features as Genuine (1920) and The Hands of Orlac (1924), he struggled to repeat his success. Indeed, only Karlheinz Martin's From Morn to Midnight (1920), with sets designed by Robert Neppach, built on Caligari 's radical approach to non-naturalism. Germany's other Expressionists took a very different tack.

Baring a Nation's Soul

Unsurprisingly, German producers sought to cash in on Caligari 's success by devising their own subjective studies of anti-heroes whose urban locales had an architectural eccentricity that reflected the dislocation and disillusion of the wretched souls dwelling in their margins and shadows. After Pommer became head of production in 1923, the centre of activity became the Neubabelsberg studios occupied by Universum-Film Aktiengesellschaft, which dominated the German film industry for the next two decades. On the UFA payroll were prolific screenwriters like Carl Mayer and Thea von Harbou, such innovative cinematographers as Karl Freund, Carl Hoffmann and Fritz Arno Wagner, as well as special effects wizards like Eugen Schüfftan, who were able to realise the visuals conceived by production designers like Herlth, Warm and Röhrig.

UFA was also home to such stars as Werner Krauss, Emil Jannings, Lya de Putti, Conrad Veidt and Lil Dagover. But, most importantly, the company offered directors of the calibre of Fritz Lang and FW Murnau the creative freedom to let their imaginations run riot in tapping into the audience's troubled psyche. In many ways, the film-makers were fortunate that sound has yet to be introduced, as it forced them into thinking visually and creating a screen language that proved to be so accessible that it remains potent a century later.

As an avid theatregoer, Lang transposed the staging ideas of Karlheinz Martin and Max Reinhardt to the studio set in order to tell tales from an audaciously varied range of times and places. While still at Decla with Pommer, Lang had Death (Bernhard Goetzke) lead a grieving widow (Lil Dagover) to an Arabian Nights citadel, 15th-century Venice and Ancient China in the hope of reuniting with her beloved (Walter Janssen) in Destiny (1921). On arriving at UFA, he invented a mind-controlling master of disguise who was prepared to resort to any malevolent means to retain his supremacy over the Berlin Underworld. Rudolf Klein-Rogge took the title role in Dr Mabuse, the Gambler (1922) and reprised it in Lang's last film before fleeing to Hollywood, The Testament of Dr Mabuse (1933).

Peter Van Eyck assumed the mantle when Lang wound down his directorial career with The Thousand Eyes of Dr Mabuse (1960) which affirms the influence that Expressionism had over the nouvelle vague. None of the Cahiers du Cinéma cabal ever attempted anything as bold as Lang's Norse duology, Die Nibelungen: Siegfried and Kriemhild's Revenge (1924), or his futuristic parable, Metropolis (1927), which all revealed his Expressionist tendencies. As did Spies (1929) and his first talkie, M (1931), which featured a career-making performance by Peter Lorre as a child killer being hunted down by Berlin's criminal fraternity.

This enduringly unsettling drama was scripted by Lang's wife, Thea von Harbou. But she chose to remain in the Third Reich after her husband decamped to Hollywood, where he cast Teutonic shadows over the action in such studies of Depression American as Fury (1936), the wartime thrillers, Man Hunt (1941) and Ministry of Fear (1944), and such nascent noirs as Scarlet Street (1945) and The Secret Beyond the Door (1947). Indeed, Lang continued to seek Expressionist inspiration throughout his American sojourn, with latter outings like The Big Heat (1953) and While the City Sleeps (1956) all plumbing the dark depths of the urban soul.

Sadly, a car crash curtailed the career of Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, whom Lotte Eisner dubbed 'the greatest film director the Germans have ever known'. Having been discovered by Max Reinhardt in a student production at the University of Heidelberg (when his surname was still Plumpe), Murnau joined forces with Conrad Veidt to open his own studio after the war. Several early offerings have been lost forever, but the influence of Expressionism was evident in Schloß Vogelöd (1921), a haunted castle chiller that also contains echoes of Louis Feuillade's fabled serials, Fantômas (1913) and Les Vampires (1915).

The stately spookiness would recur in The Finances of the Grand Duke (1924). But, like Phantom (1922), this droll adventure felt like a retrogressive step after Murnau has elevated Expressionist cinema to new heights in Nosferatu (1922). Taking its inspiration from Bram Stoker's Dracula, this unofficial adaptation bankrupted the short-lived Prana Film company when the Irish novelist's family sued for plagiarism. But Murnau took Fritz Arno Wagner's camera out of the studio confines to locate terror in everyday locations (a gambit that would not be lost on aspiring film-maker Alfred Hitchcock). Consequently, this harrowing tale of the undead proved as influential as The Cabinet of Dr Caligari and even had its genesis recreated by E. Elias Merhige in Shadow of the Vampire (2000), which boasts canny performances by John Malkovich as Murnau and Willem Dafoe as his disquieting leading man, Max Schreck.

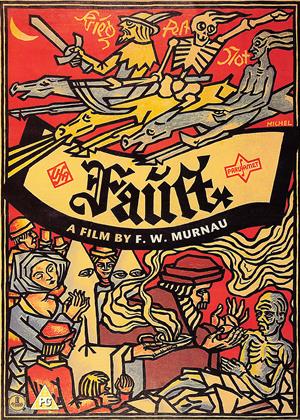

Murnau would return to the less reputable side of human nature in such literary adaptation as Tartuffe (1925) and Faust (1926). But, having become a pioneer of the Kammerspielfilm with The Last Laugh (1924), he focused on this more naturalistic 'chamber drama' style after leaving for Hollywood to make Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927). Resisting calls to graduate to talkies, Murnau reworked the town-and-country theme in City Girl (1930) before collaborating (somewhat fractiously) with pioneering documentarist Robert Flaherty on the 1931 docufiction, Tabu: A Story of the South Seas, which earned Floyd Crosby the Academy Award for Best Cinematography. However, the 42 year-old Murnau was killed two weeks before the premier and cinema lost not only a silent standout but also one of its most inspired image-makers.

Georg Wilhelm Pabst is usually grouped with Lang and Murnau in overviews of German silent cinema. But, while the influence of Expressionism can be detected in his two collaboration with American actress Louise Brooks, Pandora's Box and Diary of a Lost Girl (both 1929), Pabst favoured the realist approach associated with the Neue Sachlichkeit or 'New Objectivity' that was coursing through the German art scene. Joe May's Asphalt (1929) followed suit, although he would inflect Hollywood assignments like The House of the Seven Gables and The Invisible Man Returns (both 1940) with the same Germanic foreboding that had characterised such Danish pictures as Benjamin Christensen's Hàxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages (1922) and Carl Theodor Dreyer's Vampyr (1932), which drew on J. Sheridan Le Fanu's 1872 short story collection, In a Glass Darkly.

Among the other key works of the period was Paul Leni's Waxworks (1922), which really should be available on disc. James Whale's The Old Dark House (1932) added a dash of ironic wit, while Ewald André Dupont - who had made his name with such silent gems as Variety (1925) and Piccadilly (1929) - switched the scene of unease to a lighthouse in Cape Forlorn (1931) and, thus, provided inspiration for, among others, Michael Powell's ThePhantomLight (1935) and Robert Eggers's The Lighthouse (2019).

Hollywood Gothic

Despite the global acclaim for its films, UFA found itself in a financial bind, as inflation hit an economy buckling under the weight of postwar reparations. Therefore, in 1925, it concluded the Parufamet Agreement with Paramount and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, which saw the Hollywood studios lend UFA $4 million in return for a 75% share of screen space in its theatre chain. This meant that American pictures could flood the German market while restricting the number of imports. The deal also prompted a talent drain, as Lubitsch, Leni, Dupont, Murnau, Lothar Mendes and Hungarian Michael Curtiz seized the opportunity to work in the world film capital.

Among the performers to quit Berlin was Greta Garbo, who became one of the biggest stars in the world and caused a sensation when she made her speaking debut in Clarence Brown's adaptation of Eugene O'Neill's Anna Christie (1930). Emil Jannings won the first-ever Academy Award for Best Actor for his work in Victor Fleming's The Way of All Flesh (1927) and The Last Command (1928), which was directed by Josef von Sternberg, who would team Jannings and Marlene Dietrich in one of Germany's first talkies, The Blue Angel (1930). Von Sternberg repurposed Expressionist lighting techniques to enhance Dietrich's sense of mystery and glamour, most notably in The Scarlet Empress (1934), which boasted magnificent sets by Hans Dreier, the production designer who helped Paramount earn its reputation for continental chic.

As the political situation in Germany became increasingly unpredictable around the turn of the decade, a number of ambitious film-makers ventured out to Hollywood, including Robert Siodmak, Edgar G. Ulmer, Billy Wilder, Fred Zinnemann and William Wyler. Simply type their names into the Search line to see the contribution they made to American cinema over the next five decades. Ironically, despite the benefits that Parufamet brought MGM and Paramount, the studio to gain most from the Germanic influx was Universal, which was run by another émigré, Carl Laemmle, who had started out running a Chicago movie theatre in 1906.

Founded from the amalgamation of several small companies in Fort Lee, New Jersey in 1912, Universal joined the exodus to California three years later. However, it only struck paydirt with such Lon Chaney vehicles as Wallace Worsley's The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and Rupert Julian's ThePhantomof the Opera (1925). However, when 'the Man of a Thousand Faces' opted against making Paul Leni's interpretation of Victor Hugo's The Man Who Laughs (1928), Caligari star Conrad Veidt was offered the lead and, as a consequence, Universal became the Hollywood home of Gothic horror.

The decision to make a series of classic horror movies was made by studio boss Carl Laemmle, Jr. However, he wasn't convinced that Hungarian Bela Lugosi was the right man for the lead in Tod Browning's Dracula (1931), even though he had played Bram Stoker's vampire on Broadway in 1927. Yet, despite giving a definitive reading of the role, Lugosi never played it again, even though Universal returned to matters Transylvanian in Lambert Hillyer's Dracula's Daughter (1936), Robert Siodmak's Son ofDracula (1943) and Erle C. Kenton's House ofDracula (1945).

By contrast, cricket-loving Englishman Boris Karloff was transformed by Jack B. Pierce's iconic make-up to play the Monster in James Whale's Frankenstein (1931) and Bride ofFrankenstein (1935), as well as Rowland V. Lee's Son ofFrankenstein (1939). However, Lon Chaney, Jr. took the role in Kenton's The Ghost ofFrankenstein (1942) before passing it on to Glenn Strange for Kenton's The House ofFrankenstein (1944), in which Karloff played the Creature's demented creator, Dr Gustav Niemann.

Karloff also took the title role in Karl Freund's The Mummy (1932). However, he resisted entreaties to be swathed again and Imhotep's successor, Karis, was played by Tom Tyler in Christy Cabanne's The Mummy's Hand (1940) and by Lon Chaney, Jr. in Harold Young's The Mummy's Tomb (1942), Reginald Le Borg's The Mummy's Ghost (1942) and Leslie Goodwins's The Mummy's Curse (1944). Bandages also proved crucial to Claude Rains achieving an on-screen presence as Dr Jack Griffin in James Whale's The Invisible Man (1933). But Rains was conspicuous by his absence from Joe May's aforementioned The Invisible Man Returns, A. Edward Sutherland's The Invisible Woman (1940), Edward L. Marin's Invisible Agent (1942) and Ford Beebe's The Invisible Man's Revenge (1944).

Back in the mid-1940s, the fact that the studio had entrusted its Monsters to journeymen from the B-Hive shows that wartime audiences were more afraid of real-life menaces than spooky castles and leering ghouls.

Russian-born producer Val Lewton had a keener insight into the national mood, however, and the nine horrors he oversaw at RKO Pictures during the 1940s remain classics of their kind. Seven of these insinuating chillers are available from Cinema Paradiso. In making his RKO bow, Lewton was fortunate in being able to rely on a such skilled director as Jacques Tourneur, who made the scares in Cat People (1942) as stealthy as Simone Simon's cursed fashionista. Tourneur would also handle The Leopard Man (1943), while editor-turned-director Robert Wise made a solid impression with The Curse of theCat People (1944), which he co-directed with Austrian exile Gunther von Frisch, and The Body Snatcher (1945). The remaining titles in the Lewton canon were made by Mark Robson and his sure sense of timing, added to the typically evocative RKO settings, made The Seventh Victim (1943), Isle of the Dead (1945) and Bedlam (1946) so deeply unsettling.

Meanwhile, Universal was still peddling variations on the Expressionist theme by following Stuart Walker's Werewolf of London (1935) with George Waggner's The Wolf Man (1941) and Jean Yarbrough's She-Wolf of London (1946). When these failed to spark the public imagination, the studio tried a different tack by teaming two old favourites in Roy William Neill's FrankensteinMeets the Wolf Man (1943), which cast Lugosi opposite Chaney in the title roles.

Undaunted by the modest box office, the Universal front office pitted its popular comedy duo, Bud Abbott and Lou Costello, against their creaking creatures in a string of amusing, if only fitfully eerie romps that, among others, included Charles Barton's Abbott and Costello MeetFrankenstein (1948) and Charles Lamont's Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man (1951), and Abbott and Costello Meet the Mummy (1955).

By the time the latter titles hit cinemas, the studio had started to use horror to examine the Cold War themes that preyed on the fears of younger audiences. But Jack Arnold's Creature From the Black Lagoon (1954) and Revenge of the Creature (1955) and John Sherwood's The Creature Walks Among Us (1956) soon had competition from exploitation maverick Roger Corman at American International Pictures. Moreover, Hammer was about to revolutionise the horror genre by adding lurid colour to the mix and the Universal franchise started to seem almost quaint by comparison.

Continental Drift

While Expressionism had a profound effect on avant-garde film-making in Europe and the United States, its impact on mainstream cinema was equally evident. Having spent time at UFA in the mid-1920s, Alfred Hitchcock returned to the lessons he had learned from watching Murnau in action in order to add 'stimmung' or 'atmosphere' to pictures as varied as The Lodger (1927), Spellbound (1945), I Confess (1953) and Vertigo (1958).

The interaction between continental production companies also helped disseminate stylistic ideas. Not only did the cast feature German stars Brigitte Helm and Alfred Abel, but Marcel L'Herbier's L'Argent (1929) also combined Art Deco with the cinematic equivalents of both Impressionism and Expressionism. The latter blend also inflected Jean Vigo's L'Atalante (1934), which used visual flourishes to get inside the mind and heart of a young bride (Dita Parlo) coming to terms with life aboard a barge on the River Seine. This was one of the first features to be lauded for its 'poetic realism' and this blend of Murnau and Pabst's silent styles came to define French cinema in the decade before the Second World War.

As Bertrand Tavernier notes in A Journey Through French Cinema (2016), the mood of optimism following the election of the Popular Front government was evident in such dramas as Jean Renoir's Le Crime de Monsieur Lange (1935). But the growing bellicosity of Adolf Hitler saw the air of despondency pervading Jacques Feyder's Le Grand Jeu (1934) become more apparent in such studies of doomed anti-heroes as Julien Duvivier's Pépé le Moko (1937), Renoir's La Bête humaine (1938), and Marcel Carné’s Le Quai des brumes (1938) and Le Jour se lève (1939). Having been suppressed by the Nazis, the latter was remade in Hollywood by Anatole Litvak as The Long Night (1947) and Carné's proto-noir masterpiece destroyed luckily survived an attempt by RKO to safeguard its film by having all existing prints destroyed.

Draped in the looming shadows bequeathed by German cinematographers Curt Courant and Eugen Schüfftan during their Gallic sojourns and staged against the imposing studio realist sets designed by Lazare Meerson and Alexandre Trauner with a nod to the Kammerspielfilm and Strassenfilm, these harbingers of the Occupation of June 1940 anticipated the style that became known as film noir. However, noir also retained its validity in postwar France, in such lowering studies of a scarred country as Henri-Georges Clouzot's Le Corbeau (1943) and Les Diaboliques (1955), Jules Dassin's Rififi (1955) and Jean-Pierre Melville's Le Doulos (1962).

Blending Expressionism with a humanism that was rare in much horror in the early days of exploitation, Georges Franju's Eyes Without a Face (1960) revived the 1920s themes of madness, alienation, sexuality and paranoia that fed into both the gialli produced by such Italian auteurs as Mario Bava, Lucio Fulci and Dario Argento and the surrealist eroticism that was the speciality of Frenchman Jean Rollin and Spaniard Jesus Franco. Once again, a little judicious searching of the Cinema Paradiso site should take you into the disconcertingly dislocated realm of Euro Horror.

As mentioned earlier, the iconoclastic film-makers of the nouvelle vague latched on to Expressionism in challenging the form of polished studio cinema that they had dismissed in Cahiers as the Tradition of Quality. Among the films to evoke the descendants of DrCaligariwere Louis Malle's Lift to the Scaffold (1958), Jean-Luc Godard's Alphaville (1965) and François Truffaut's The Bride Wore Black (1968).

Tantamount to Expressionism lite, noir was seized upon by Hollywood film-makers seeking to reflect America's shifting mindset as a victory against the Fascist Axis was followed by the tense nuclear standoff against the Soviet Union during the Cold War. So many noirs were produced between John Huston's The Maltese Falcon (1941) and Robert Wise's Odds Against Tomorrow (1959) that this will have to be a topic for another day. And the same goes for neo-noir and British noir. However, no exploration of the influence of Expressionism would be complete without a mention of Carol Reed's shadow-strewn Odd Man Out (1948) and The Third Man (1949). The latter starred Orson Welles, who had revealed his own debt to silent German cinema with the distorted perspectives he concocted with cinematographer Gregg Toland and production designer Van Nest Polglase on Citizen Kane.

The Shadow Continues to Creep

New waves and aesthetic trends have come and gone, but Expressionism (or Neo-Expressionism, as some insist on calling it) retains its cinematic significance. These days, the films that exploit its oblique angles and ominous umbrae tend to stand alone. But the Teutonic influence can still be felt in the visual stylisation that modern blockbusters have imported from comic-books, manga and graphic novels. Check out the scenery behind any Marvel or DC superhero and you're likely to be confronted with an Expressionist cityscape.

Curiously, the modern event movie also owes something to the animated features from a less likely source. Walt Disney was very much aware of the power of Expressionist imagery, with sinister shadows, twisted tree branches and canted architectural features cropping up in several Silly Symphonies, as well as such features as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) and Fantasia (1940). Over at Warners, the Looney Tune and Merrie Melodie strands often made use of Expressionist tropes, as did the Tom and Jerry romps produced at MGM by Fred Quimby. Samples of all are available to rent from Cinema Paradiso.

These cartoons clearly impacted upon Tim Burton, who has regularly sought inspiration from 1920s German cinema in everything from Frankenweenie (2012) to his collaborations with Henry Selick on The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993) and Mike Johnson on The Corpse Bride (2005). The debt is equally evident in such Johnny Depp outings as Edward Scissorhands (1990) and Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (2007), while it's not hard to discern the origin of the Gotham City in Batman (1989) and BatmanReturns (1992). Indeed, Christopher Walken's character in the latter was called Max Shreck, who clearly has ties to the creepy star of Murnau's Nosferatu.

But Expressionism's tendrils have wrapped themselves around features as diverse as Charles Laughton's The Night of the Hunter (1955), Jan Nemec's Diamonds of the Night (1964), William Friedkin's The Exorcist (1973), István Szabó's Mephisto (1981), Alan Parker's The Wall (1982), Lars von Trier's The Element of Crime (1984), Darren Aronofsky's Pi (1998), Takashi Shimizu's The Grudge (2004), Frank Miller's Sin City (2005), Martin Scorsese's Shutter Island (2010) and Miguel Gomes's Tabu (2012).

Straying into arthouse territory, a number of key creators have dabbled in the dark arts. David Lynch has frequently quoted Expressionism in the likes of Eraserhead (1977) and Mulholland Drive (2001). Moreover, the small town that hosted Twin Peaks (1990-91) was every bit as weird a place as Caligari's Holstenwall. A distinctive form of Expressionist deadpan also characterises the Baltic noir offerings of Finn Aki Kaurismàki, particularly in the proletariat trilogy of Shadows in Paradise (1986), Ariel (1988) and The Match Factory Girl (1990). However, the velvety shadows are at their most bewitching in Juha (1999), a reworking of Juhani Aho's noted novel that tips the wink to Murnau's Sunrise in shifting the story of a farmworker losing his wife to a city slicker from the 18th-century to the 1970s.

Hungarian Béla Tarr also favoured high-contrast monochrome images and the Expressionist legacy is plain to see in such complex, but compelling works as Damnation (1987), Werckmeister Harmonies (2000) and The Turin Horse (2011). Canadian Guy Maddin is more accessible and it's a great shame that his knowing harkenings to the Germanic past are not currently available on disc. But Cinema Paradiso users can relish the treats in store in Dracula: Pages From a Virgin's Diary (2002) and Keyhole (2011).

Even Maddin's cod-autobiographical documentary, My Winnipeg, slyly references the Expressionist style. But the most assured recent homage to the heyday of Wiene, Lang and Murnau is Argentinean Esteban Sapir's La Antena (both 2007), which takes place in an Orwellian future in which voiceless humans are completely under the control of Mabuse-like media baron named Mr TV (Alejandro Urdapilleta). He is determined to use a femme fatalistic singer named La Voz (Florencia Raggi) to reinforce his grip on civilisation. But he hasn't banked on young Ana (Sol Moreno) and her resourceful nurse mother (Julieta Cardinali) and inventor father (Rafael Ferro) thwarting his schemes. Reportedly only costing $1 million, this innovative throwback to the silent era is bullishly played. But its real glory lies in Daniel Gimelberg's production design and Cristian Cottet's photography, which affirm the enduring influence of The Cabinet of Dr Caligari and its nightmare-inducing acolytes.