It's going to be a busy summer of football. Scotland and Wales's men have crucial World Cup qualifiers, while England and Northern Ireland's women will be competing in the Euros. To get you in the mood, Cinema Paradiso lines up a showdown between two of the finest footballing films ever made.

When it comes to films about women's football, it has to be said, it's a pretty limited field. It doesn't help that a number of American movies haven't been released on disc in this country. Nor has Julien Hallard's Let the Girls Play (2019), which chronicles the founding of the Reims Women's team. But Cinema Paradiso users can still catch Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen in David Steinberg's Switching Goals (1999) and Amanda Bynes in Andy Fickman's She's the Man (2006), as well as the Iranian girls trying to defy the law by sneaking into a World Cup qualifier in Jafar Panahi's Offside (2006).

Given the paucity of titles about women's football, it's even more remarkable that it has been the subject of two bona fide classics. Bill Forsyth's Gregory's Girl (1980) raised the profile of what was still a minority sport, while also creating the template for the kind of British independent film-making that was exemplified by Stephen Frears's My Beautiful Laundrette (1985), Danny Boyle's Trainspotting (1996) and Gurinder Chadha's Bend It Like Beckham (2002).

The latter was not only a landmark in British Asian cinema, but it also inspired a generation of girls to play football. Twenty years after it's release, the FA Women's Super League is thriving, as is the Scottish Women's Premier League. But, when it comes to the cinematic title, will it be Dorothy or Jess and Jules who get your vote?

GREGORY'S GIRL

When Bill Forsyth directed That Sinking Feeling (1979), there was no such thing as a Scottish film industry. Occasional tele-dramas drew enthusiastic reviews, such as John Mackenzie's Just Another Saturday (1975), a story set against an Orange Order march in Glasgow that features a young Billy Connolly and can be rented from Cinema Paradiso on Play For Today, Volume 3. The majestic scenery had attracted occasional projects like Michael Powell's The Edge of the World (1937) and The Spy in Black (1939), while the Scottish character lent itself well to quirky comedies like Alexander Mackendrick's Whisky Galore! (1949) and The Maggie (1954), Frank Launder's Geordie (1955), and Charles Crichton's The Battle of the Sexes (1960).

But not even hits like Ronald Neame's adaptation of Muriel Spark's The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1969) or Robin Hardy's horror hit, The Wicker Man (1973), could kickstart cinema north of the border. After spending several years making industrial shorts, Forsyth was on the verge of giving up the ghost. 'I'd done it for six or seven years, and there wasn't even a living in it,' he told one interviewer.

'It seemed to me that if I wanted to make any features at all, I should try to get some experience working with actors. I thought that working with kids would be an easy way into that.' He admitted it was 'an act of desperation', but spending three years getting to know the hopefuls at the Glasgow Youth Theatre could just throw up an idea. The result was Gregory's Girl.

Match Report

Much to the dismay of 16 year-old striker Gregory Underwood (Gordon John Sinclair), the football team at his Cumbernauld school has just gone down to its eighth consecutive trouncing. In desperation, coach Phil Menzies (Jake D'Arcy) holds an open trial on the blaes pitch and by far the best player to emerge is Dorothy (Dee Hepburn). He has misgivings about picking a girl to play against boys, but Dorothy knows her rights and Phil has no option but to play her up front.

Initially disgruntled at having to replace Andy (Robert Buchanan) in goal, Gregory quickly overcomes his qualms about having Dorothy as a teammate when he gets a crush on her. Indeed, he is so smitten that he objects to opposition players kissing her after she scores a goal ('That's the sort of thing that gives football a bad name!')

Gregory wants to ask Dorothy on a date, but he's too bashful. Andy and his silent sidekick Charlie (Graham Thompson) are equally clueless when it comes to talking to girls. So, Gregory seeks advice from his pal, Steve (William Greenlees), who is such a wizard in the kitchen that he takes cake orders from the other pupils and even the headmaster (Chic Murray). But he's not much of a ladies' man, either and it's Gregory's 10 year-old sister, Madeline (Allison Forster), who advises him to pluck up the courage and just ask.

Much to Gregory's surprise, Dorothy agrees to go out with him. But she's much too busy practicing trapping the ball and turning to give up an evening. Moreover, she knows that girls help each other out. Consequently, on the big night, she sends Carol (Caroline Guthrie) and Margo (Carol Macartney) to keep Gregory occupied until Susan (Clare Grogan), who secretly fancies him, is ready to take over. They walk to the park, where they lie on the grass and dance with their arms in the air until dusk so that gravity can help them cling to the Earth's surface.

He Shoots, He Scores

Although Grange Hill (1978-2008) had started to attract a devoted teatime following on the BBC, school life as most British kids would have recognised it rarely appeared on television, let alone on the cinema screen. But, having forged a working relationship with Gordon John Sinclair (he would later shuffle the order of his first names to avoid clashing with another actor), Robert Buchanan, Billy Greenlees and Allan Love on That Sinking Feeling (which cost the princely sum of £8000), 34 year-old Bill Forsyth was keen to capture the sights and sounds at a typical Scottish comprehensive.

Sinclair had enjoyed his time at the Glasgow Youth Theatre, which had curated a 1979 episode of Something Else, a trendy magazine show produced by the BBC's Community Programme Unit. But he wasn't sure he was cut out for acting and had started work as an apprentice electrician when Forsyth turned up on his doorstep to offer him the part of Gregory. Sinclair took some persuading, but quickly got into the swing of things. Ironically, he was a bit in awe of Dee Hepburn, who was considered a cut above by her castmates because she had played Maggie in ITV's reworking of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1978). Forsyth, however, had noticed her dancing in a commercial for a local department store.

By contrast, Clare Grogan was discovered at a Glasgow eaterie, although she and Forsyth have different memories of the initial encounter. She recalls waitressing at the Spaghetti Factory and dismissing his offer of a part in a film because her mother had taught her not to give her phone number to strange men. However, Forsyth insists he was in the restaurant with fellow director Michael Radford (of White Mischief, 1985 and Il Postino, 1994 fame) and it was he who had approached Grogan on Forsyth's behalf. 'I was just sitting there dumb and nodding my head,' he told BBC Scotland.

Unbeknown to Forsyth, the 17 year-old Grogan had a dual life, as she was also the singer of the new wave band, Altered Images, who would be signed by Epic Records during the shoot. As she didn't think her music and acting overlapped, Grogan kept them in separate compartments. However, while at a gig at the Glasgow College of Technology, she was hit in the face by a flying glass during a stramash that left her with a three-inch scar on her left cheek. As shooting was due to commence in three months and Grogan refused to have plastic surgery, Forsyth was under pressure to recast the role of Susan. But he remained loyal and reworked shots to favour Grogan's right side. When the combination of angles, budget and a Louise Brooks bob confounded him, he resorted to Derma Wax make-up.

Speaking of finance, Forsyth had approached producer David Puttnam with the screenplay. Fortunately, Davina Belling and Clive Parsons proved more perceptive, as they had enjoyed success with such youth-oriented films as Harley Cokeliss's That Summer!, Alan Clarke's Scum (both 1979) and Brian Gibson's Breaking Glass (1980). Moreover, they were canny enough to know that Scottish Television (STV) was facing franchise renewal negotiations and could be persuaded that stumping up half the £200,000 budget would underline its commitment to the community.

Meanwhile, across the city, Hepburn was on a six-week footballing crash course at Partick Thistle. As she had never played before, she was coached by both Donnie McKinnon (whose twin, Ronnie, had played for Rangers and Scotland), and goalkeeper Alan Rough. Somewhat ignominiously, he had been part of Ally MacLeod's Scotland squad that had been knocked out of the World Cup in Argentina in 1978 after drawing with Iran and losing to Peru. However, Rough and McKinnon worked such wonders with Hepburn that she was able to do keepie-uppies for 40 minutes and was frustrated that the film didn't fully showcase her skills.

As cash was tight, the production office became a burger bar to feed the cast and crew, while the principals were often required to wear their own clothes. Grogan's date outfit reflected her passion for silent movie stars, while Hepburn borrowed her white shorts from one of her four sisters. Forsyth recruited extras from Abronhill High School to reduce the number of uniforms he had to supply. But the school also proved a wonderful location: the expansive playground that Gregory zig-zags after arriving late; the bathrooms where Steve and Eric (Allan Love) do a brisk trade in cakes and photos of Dorothy; the classroom where Gregory adds 'ti lo diró' to 'bella bella' in his lexicon of Italian phrases; the corridors wandered by the lost child (Christopher Higson) in the penguin suit; and the music room with the upright piano that allows the headmaster insouciantly to tinkle the ivories while growling, 'Off you go, you small boys!'

Despite Forsyth shooting during the school holidays, things often conspired against him. As 1980 was the wettest summer for 73 years, the shale football pitch kept changing colour. Furthermore, numerous takes were ruined by the chimes of ice-cream vans roving the nearby estate. Perhaps that's why Forsyth chose the infamous Glasgow Ice Cream Wars as the subject for his 1984 outing, Comfort and Joy?

Nevertheless, he made splendid use of the Westfield housing estate and landmarks like the St Enoch Clock in New Town Plaza and the Abronhill chip shop for Gregory's tag-along date. This culminates at Cumbernauld House Park, where Gregory and Susan discuss why boys like numbers and how girls help each other out. As Sinclair later recalled, 'I especially remember the scene after the date in the park, where there's a shot of us walking off into the sunset. Clare Grogan and I were both in tears. It was the last day of filming. It was all over. This magical bubble we'd been in was about to burst.'

However, there was one last serendipitous moment to celebrate. As Andy and Charlie can't get anywhere with Scottish girls, they decide to hitch to the Venezuelan capital, Caracas, as they have heard that women there outnumber men by eight to one. While they were filming on a busy road, Forsyth noticed that production designer Adrienne Atkinson had mistakenly put 'Caracus' on the boys' cardboard sign. Rather than correct the spelling, however, he reworked the scene so that the previously silent Charlie could reassure his friend that things will work out.

Post-Match Analysis

Scotland was at a low ebb in 1980. The Winter of Discontent had been followed by a fractious referendum campaign on devolution. Consequently, the country was in need of cheering up and Gregory's Girl became not only a means of escape, but also a source of national pride, particularly after Forsyth beat Colin Welland to the BAFTA for Best Original Screenplay and Hepburn was named the Variety Club's actress of the year.

The film would eventually form part of a double bill with Hugh Hudson's Oscar-winning Chariots of Fire (1981), while in the process of claiming Sassanach hearts. Indeed, it played in one London cinema for 75 consecutive weeks. While visiting the capital, Hollywood producer Samuel Goldwyn, Jr. was encouraged to see the picture by a hotel receptionist and he was so smitten that he sought US distribution rights. However, having taken a box-office hit when nobody Stateside could understand the Yorkshire accents in Ken Loach's Kes (1969), Goldwyn insisted hiring voice actor Robert Rietti to supervise the redubbing of the dialogue so it sounded less Glaswegian.

The cast might have been dismayed by this development, but it helped charm the American media and boost the global take to £20.8 million. Variety compared Forsyth to the great French director, René Clair, whose credits include A Nous la liberté (1931), The Ghost Goes West (1935) and It Happened Tomorrow (1944). Influential critic Roger Ebert enthused that Forsyth had included 'so much wisdom about being alive and teenage and vulnerable' that Gregory's Girl' is one of the rare movies that has the courage to admit that some teenagers can be immature and insecure. It remembers adolescence, it observes it lovingly with sympathy and good humour and, with what teenage boys probably need most, compassion.'

Forsyth himself felt the film was accepted 'because it didn't patronise anyone; there was a level of honesty that you don't normally get in teen films'. The absence of mean-spirited characters and swaggering studs certainly distanced the picture from bawdier counterparts like Boaz Davidson's Lemon Popsicle (1978) and Bob Clark's Porky's (1981). However, the opening scene, in which Gregory and his pals spy on a nurse undressing in her room, has not worn well. Nor have the smirking staffroom allusions to the emotional vulnerability of hormonal, poetry-writing redheads or the smutty on-the-job anecdotes of old boy Billy (Douglas Sannachan), which reinforced the stereotypes in contained Val Guest's Confessions of a Window Cleaner (1974).

While Chadha sought to bend the rules, Forsyth was content to impart a little spin. As Grogan told an interviewer, 'I love all the role reversal...And it's the girls who manipulate all the events in the film.'

Dorothy doesn't just play football. She and Susan are shown doing chemistry experiments, while Gregory and Steve are in home economics. The female classmates are more grown-up in every regard, as is Madeline, who understands much more about love than her naive older brother. Amusingly, this gag about maturity extends to the staff, as Alec (Alex Norton) and Alistair (John Bett) tease Phil about his moustache. It's just a shame that Miss Welch (Muriel Romanes) has to flirt with Billy in such a seductive spinsterly manner after Miss Ford (Maeve Watt) had handled Gregory's inquiry about Italian lessons with such disarming tact.

Despite its minor indiscretions, Gregory's Girl continues to retain the nation's affection. It's a nostalgic snapshot of a time before mobile phones, crass celebrity, social media cynicism and online pornography. Such is its elegy for youthful innocence and hope that it drew a sigh of fond recognition when Frank Cottrell Boyce and Danny Boyle included a clip in the 'Isles of Wonder' segment of the opening ceremony of the 2012 Olympics (which can be rented from Cinema Paradiso as part of London 2012 Olympic Games).

Perhaps that's why the 1999 sequel, Gregory's Two Girls, failed to strike a chord. Nobody wanted to see that things hadn't gone according to plan for the now 35 year-old Mr Underwood (still Sinclair), who is teaching at his old school and is caught up in unprofessional liaisons with a student, Frances (Carly McKinnon), and a colleague, Bel (Maria Kennedy Doyle). Erring more on the side of Sam Mendes's American Beauty than Alexander Payne's Election (both 1999), the film left critics and audiences feeling let down and Forsyth hasn't made another feature since.

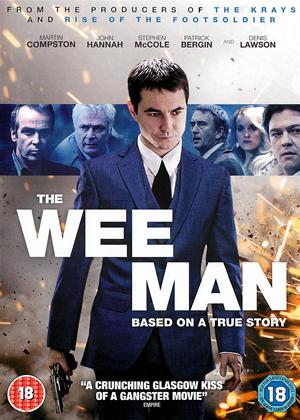

Hepburn and Grogan opted not to return. The former had retired from acting after being inundated with offers to strip off on camera. However, she did put in a three year mid-80s stint in as motel receptionist Anne-Marie Wade in the daytime soap, Crossroads (1966-88). Away from her pop career (which she guyed in Father Ted, 1996), Grogan also enjoyed brief small-screen success in Red Dwarf (1988-2020) and Skins (2007-13). She also took roles in films like Philip John's Wedding Belles (2007), Ray Burdis's The Wee Man (2013) and Chris Cook's The Penalty King (2006), which took her back into the world of football.

As the 50-year FA ban on organised women's football had only been lifted in 1971, Gregory's Girl perhaps came too soon to have a seismic impact on the game across the UK. The story of women's football in this period, and the exploits of the famous Dick Kerr Ladies team, is told in Kelly Close's documentary, When Football Banned Women (2017), which really should be available on disc. But Dorothy and her sky blue shirt remained in the female sporting and cinematic consciousness and, after what seemed an inordinately lengthy period of extra time, she was eventually followed by another member of the footballing sisterhood, whom critic Philip French dubbed, 'Arundhati Roy of the Rovers'.

BEND IT LIKE BECKHAM

Fast forward 22 years. In all that time, only one British film of note has depicted girls interested in football. Scripted by sports journalist Julie Welch, Philip Saville's Those Glory Glory Days (1983) was sponsored by Film Four and followed four teenagers desperately trying to raise the money to see Tottenham Hotspur take a tilt at the League and Cup double at Wembley in 1961.

But that was it. The film addressed the issues of conservative parents disapproving of their daughter's passion for the beautiful game and how teachers tried to demonstrate how Greek dancing was a healthier pursuit than daydreaming about the Spurs captain, Danny Blanchflower. But critics complained that the moping mothers and strict schoolteachers were caricatures that no longer existed in a Britain under its first female prime minister.

Margaret Thatcher didn't like football and made no attempt to hide her disdain for the hooliganism that had become known as 'the English disease'. No one, therefore, was going to make a film about girls playing football, when the sport was niche at best and social realist film-makers had weightier issues to tackle as Thatcherism sought to change the essential nature of British society.

Perish the thought that anyone in this period would have considered making a film reflecting the real and lived experiences of British Asian girls. Such was the blinkered vision of the British film industry of the time that pictures like Horace Ové's Playing Away (1987) - in which an Afro-Caribbean cricket team from Brixton is invited to play a charity match in an insular country village - were a rarity, while the representation of the Black and South Asian communities on television barely rose above the patronisingly stereotypical.

All of which makes Gurinder Chadha's Bend It Like Beckham so remarkable. No film before or since has explored how British Asians deal with the legacy of bigotry that their parents experienced on first coming to the UK. Yet, while wanting to repay these sacrifices and respect subcontinental culture and traditions, British Asian children also wanted to make their own decisions and benefit from the freedoms that their classmates and neighbours took so much for granted. Hence the popularity of Damian O'Donnell's East Is East (1999) for the way it challenged accepted notions of immigration, integration and intolerance.

Chadha took up the baton, but narrowed the focus to British Asian girls in order to show there was more to life than getting good grades, learning to cook and securing a suitable husband. Community remained important, but forging an identity both within and without it was the right of every girl and boy, regardless of what their elders may think. No wonder young Asian audiences rejoiced in 2002, because someone had made a movie that understood them and their situation.

Match Report

In her bedroom in Hounslow, Jesminder Bhamra (Parminder Nagra) dreams of John Motson commentating on her scoring a goal from a cross by David Beckham. Jess is listening to Gary Lineker discussing her England prospects with pundits Alan Hansen and John Barnes when she is brought back to reality with a bump. Her older sister, Pinky (Archie Panjabi), is about to get married and Sikh parents Mohaan (Anupam Kher) and Sukhi (Shaheen Khan) expect her to play her part in the big day.

However, Jess is further distracted when she is spotted having a kick about in the park with Tony (Ameet Chana) and his mates by Juliette Paxton (Keira Knightley), who invites her for a trial with her women's football team, Hounslow Harriers. Irish coach Joe (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) is keen to sign Jess up. But he is uneasy about the fact she is going behind her family's back to play and comes to the house to appeal to her father. Mohaan is disappointed with Jess and reveals that he is simply trying to shield her from the kind of pernicious racism he had experienced after arriving from East Africa in the 1970s and being discriminated against when he tried to join the local cricket team.

Having been driven by his own father and then disowned after suffering a career-ending injury, Joe doesn't want to come between Jess and Mohaan. But Pinky realises how much football means to her sister and covers for her when the Harriers travel to Hamburg. Unfortunately, Jess misses a penalty and upsets Jules at a nightclub when she catches her in an intimate embrace with Joe.

Back in Hounslow, Jules's mother, Paula (Juliet Stevenson), overhears Jules and Jess arguing and leaps to the conclusion they are having a lover's tiff. She has always tried to convince Jules that football isn't ladylike ('There's a reason why Sporty Spice is the only one without a fella!') and wishes she would quit the team. But Mohaan decides to see for himself why Jess is so committed. He's enjoying her performance until she is sent off for responding to a racist insult and he is appalled when he catches Joe consoling his daughter behind the changing room.

Consequently, even though an American scout is coming to the championship decider, Jess is forbidden to play, as the game coincides with Pinky's wedding. Her chance of fulfilling her dream seems to be over. But, as we all know, football's a funny old game...

She Shoots, She Scores

Born in the Kenyan capital, Nairobi, in 1960, Gurinder Chadha was two years old when she moved to Southall in London. Her Sikh father opened a shop, as he was unable to continue his previous career in banking. Refusing to wear Indian clothes or accept traditions about women doing the cooking and eating apart from their menfolk, Chadha initially went into radio after studying at the University of East Anglia. Following a stint as a TV news reporter, she started making short films, with I'm British but... (1989) revealing how British Asians had gained a degree of cultural autonomy and social self-confidence through Bhangra music.

Exploring generational and cultural tensions within the British Asian community, as well as themes like inter-racial romance and domestic abuse, Bhaji on the Beach (1993) became the first feature to be directed by a British Asian woman. It was nominated for Best British Film at the BAFTAs and established Chadha as an important voice in a film industry that was still dominated by white males. Yet, despite the film making a solid profit on its modest outlay, Chadha didn't make another film until What's Cooking? (2000), a Hollywood bow that focussed on how Vietnamese, Latino, Jewish and African American families celebrate Thanksgiving.

Chadha co-wrote the picture with American husband, Paul Mayeda Berges. But she was keen to make a feature that reflected the experiences of so many young women in the UK diaspora and the pair teamed with Guljit Bindra to set a girl power comedy in the satellite town of Hounslow, which had frequently cropped up in sketches on Goodness Gracious Me (1998-2000), a BBC comedy show about the British Asian experience that was written and performed by Sanjeev Bhaskar, Meera Syal, Nina Wadia and Kulvinder Ghir.

While she wanted to examine topics like assimilation and prejudice, Chadha was also keen for Bend It Like Beckham to show how much Jess and Jules had in common. Modelling Jess's parents on her own, she completed the first draft of the screenplay in a fortnight and started adding comic subplots and the complexities caused by the girls falling for the man who coached their football team. She also accommodated the scarring on Parminder Nagra's leg by including the story of how she had burnt herself while trying to cook baked beans as a child. Nevertheless, Nagra took some persuading that the story would attract an audience ('why would anybody want to watch that?'), while Jonathan Rhys Meyers had to be talked into the project by his brother because he thought it sounded 'terrible'.

Initially, Guljit had insisted that the famous footballer should be David Beckham's Manchester United teammate, Ryan Giggs. However, Beckham's relationship with Spice Girl Victoria Adams chimed in with Chadha's eagerness to celebrate girl power. Moreover, the connection with Posh and Beck gave the film the kind of tabloid cachet that was impossible to buy.

In order to get Nagra and Keira Knightley into shape, Chadha hired coach Simon Clifford to put them through three months of rigorous training. Changing in the local pub, the pair perfected their skills on Clapham Common for up to eight hours a day. Knightley got the odd concussion from heading the ball, while Nagra lived in fear of breaking a toe. But Clifford was particularly impressed by Knightley and claimed, 'If I'd trained her from the age of 10 or 11, without a shadow of a doubt Keira could have been a pro.' However, she was more sceptical in a magazine profile, in which she revealed, 'I was captain of the girls' team in primary school, but we never actually scored a goal. We only kicked people.'

Monitoring their progress, Chadha told the actresses that she could always use doubles if necessary. But they were determined to do the football scenes themselves, with Nagra only needing one take to bend the ball around the clothes on the washing line in the Bhamra's back garden. However, Chadha did surround the duo and their All Saints co-star, Shaznay Lewis, with players from local teams in order to ensure the sporting sequences looked authentic. Further to this end, the action was filmed at the ground of Yeading FC in West London. It didn't prove a lucky omen, however, as the club folded in 2007 before merging with another from the Conference South to form Hayes and Yeading United.

But the Hounslow Harriers formed a bond and pleaded with Chadha to let them play against the German team she had found for the Hamburg visit. 'They more than held their own in a match that was extremely intense.' Chadha later recalled. 'The girls refused to lose, they had completely forgotten the script and they begged me to let them keep playing until they could give the German side a good stuffing. The most bizarre thing was how the crew went berserk supporting our girls against the German girls!'

Clifford also advised on the football choreography, as he had on John Hay's There's Only One Jimmy Grimble (2000), which followed the fortunes of a young lad who dreams of turning out for Manchester City. The same year had also seen the release of Mark Herman's Purely Belter, in which a couple of pals try to raise the money for season tickets at Newcastle United. Both films are available from Cinema Paradiso, as is David Bracknell's Cup Fever (1965), which can be found on the BFI's Children's Film Foundation Bumper Box. As Man Utd manager Matt Busby takes a cameo, this would make for a fine double bill with David Scheinmann's Believe (2013), in which Brian Cox plays Sir Matt coaching a team of backstreet scamps.

Despite Clifford's expertise, football is notoriously difficult to stage on screen with any degree of matchday realism. As in Gregory's Girl, therefore, the play is very much of a grassroots level, with Chadha keeping Jong Lin's handheld camera on the move so that she could not only convey the kineticism of the action, but also help editor Justin Krish disguise the fact that the kick, rush and dribble nature of play would hardly have enticed a top American scout with a fistful of contracts and scholarships.

While we're on the football side of things, it's worth noting that a film about bending the rules does just that in ensuring that Jess doesn't miss the big match. As she has been sent off for lashing out at a racial slur, she would surely have been suspended for the next game - making her ineligible for the title decider. The league is clearly sufficiently sophisticated for this protocol to be in place. Similarly, coaches would have to submit a starting XI and the list of substitutes before kick-off. As Jess had told Joe that she can't go against her family, he would not have put her on the bench on the off-chance she would show up for such an important game. Therefore, when she racks up at the ground after having changed from a sari into her kit in the back of Tony's car, she would not have been able to go straight on to the pitch with half an hour to go. Jess the Super Sub makes for a better ending, however, so Chadha (who admits to having known little about football when she wrote the script) was never going to let the rules stand in the way of a good story. And that's most certainly what this is!

Post-Match Analysis

Despite its title, Bend It Like Beckham was actually inspired by Ian Wright, after Chadha became aware of the integrational potential of football after seeing the Black Arsenal striker wrapped in the Union Jack while watching a World Cup qualifier in a Camden pub. She was glad she stuck with Becks, however, as, with the 2002 World Cup looming, the entire country was obsessed with the state of his metatarsal in the week of the film's release.

You couldn't buy such publicity, although there was talk of changing the title for US audiences unfamiliar with Golden Balls to Move It Like Mia, after Mia Hamm, the women's international who is Jules's role model in the movie. But the marketing strategies were very different either side of the Atlantic, as what was seen as primarily a feel-good chick flick Stateside was viewed as a state of the nation report from a uniquely female and second generational immigrant perspective.

There simply hadn't been a film like this before, as British Asian girls got to see their lives on screen for the first time. No wonder the picture topped the box-office charts for 13 weeks and grossed almost £60m on a £3.5m budget. But its reach extended much further, notably into North Korea, where film buff Kim Jong-il included it in the 2004 Pyongyang Film Festival, where it was seen by 12,000 people. Six years later, Bend It Like Beckham became the first Western film to be shown on North Korean television, albeit in a much-truncated version. Of course, the countries already had a footballing link, as North Korea had reached the quarter finals of the 1966 World Cup, as Daniel Gordon reveals in The Game of Their Lives (2002), a documentary that really should be available on disc.

Fortunately, Cinema Paradiso users can enjoy a number of other films about sport that have encouraged women and girls to get involved. Among them are Penny Marshall's A League of Their Own (1992), Gina Prince-Blytewood's Love & Basketball (2000) and Jessica Bendinger's Stick It (2008), while the way in which Jules is supported by her father, Alan (Frank Harper) recalls the way in which dad John Cena tries to get his biracial daughter to like sports in Kay Cannon's Blockers (2018).

'I think people underestimated the power of girls wanting to see films where they were empowered,' Chadha explained. On the footballing front, the story had a truly motivational effect, as thousands started to play the game and/or support their nearest team. Such was the groundswell that the professional Women's Super League was founded in 2011 and FA figures for 2020 reveal that 3.4 million girls and women now play football in the UK, making it easily the most popular sport.

For British Asian audiences, however, the sport was less significant than the social satire. There may be a touch of caricature about both Mrs Bhamra and Mrs Paxton, but they shared an idealised image of what a daughter should be and this alllowed Chadha to explore the kind of generational and culture clashes that she had experienced growing up and had never seen reflected in films and television programmes.

The genius of Jess is that she constructs her own hybrid personality by blending aspects of her life inside and outside the family circle. Thus, while she can learn to cook and wear a pink sari to her sister's wedding, she can also express herself on the pitch and bond with people from her neighbourood rather than just her tightly knit community. As Chadha divulged, being a British Asian girl was about playing the game, but by her own rules.

Hence the significance of the eponymous reference to David Beckham's trademark free kicks. The bending ball, Chadha noted, was 'a great metaphor for a lot of us, especially girls. We can see our goal but instead of going straight there, we too have to twist and bend the rules sometimes to get what we want - no matter where "we" reside, no matter what group "we" claim or do not embrace as part of "our" ethnic lineage.' Consequently, when Jess lines up the last-minute shot, she imagines the defensive wall being made up of her female relatives, as she has to swerve around them in order to fulfil her goal.

Ironically, this progressive statement about young women seizing their own destiny runs the risk of falling foul of the Bechdel test that assesses the extent to which female film characters are shaped by their (romantic) relationship to men. By having both Jess and Jules fancy Joe, Chadha and her co-writers place undue emphasis on a player-coach situation that would now be frowned upon. They also rather misjudge Joe's empathetic utterance after Jess is racially abused ('Jess, I'm Irish. Of course I understand what that feels like.'), while the bid to make him seem vulnerable by giving him a wrecked career and a hectoring father also feels somewhat strained.

Such unconvincing moments are rare, however, although it was a smart move to end on an upbeat note after the original scenario had Jess returning to Hounslow to help her mother after her father had died (as Chadha's had during filming). Moreover, by having Mohaan survive and approve of his daughter's choices, the director was able to subvert the Bollywood tendency to uphold patriarchal control and the class and caste systems. Indeed, by having Jess and Jules thumb their noses at such conventions, the film has become a firm LGBTQ+ favourite - and not just because Tony 'really' likes Beckham.

This combination of specificity and diversity helps explain Bend It Like Beckham's enduring appeal. Times have changed and gender norms are more openly critiqued than they were two decades ago (which makes the film even more boldly innovative). Yet, disappointingly few film-makers have built on its success by tackling topics that Desi girls can relate to in a post-9/11 world in which third- and fourth-generational ties with the subcontinent have become weakened.

Chadha herself returned to the theme in Bride and Prejudice (2004) and the musical version of Bend It Like Beckham (2015), which was scored by Howard Goodall and Charles Hart. But, even though the feature has become part of the curriculum for GCSE and A Level Film Studies, Britain has yet to unearth its own Mindy Kaling to front shows like The Mindy Project (2012-17). Then again, since Nagra became the first woman to win the FIFA Presidential Award in 2002, British Asian footballers like Aman Dosanj, Simran Jhamat, Rosie Kmita, Kira Rai and Millie Chandarana have been few and far between. We live in hope, however.

Up For the Cup

So, you have heard the case for each film. Now, it's up to you to decide who wins the Cinema Paradiso Cup.

All you have to do is cast your vote here for

Perhaps you might like to share the thinking behind your decision on Facebook or Instagram?

Keep an eye on our social media pages for the big result. We'll let you know on the day England kick-off the Euros against Austria on 6 July.

That gives you plenty of time to rent the films from Cinema Paradiso and make up your mind which is the best British film about women's football.