Cinema Paradiso celebrates the 60th anniversary of A Hard Day's Night by exploring how Richard Lester made a 'day in the life' film that shifted how the world perceived The Beatles.

Sixty years ago, a film opened that helped change Britain. Beatlemania had already done much to lower the class barrier. But A Hard Day's Night (1964) showed how four lads from Liverpool handled the pressure of unprecedented celebrity by being themselves. Whether frequenting higher echelons or fleeing from screaming fans on the streets, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr were living proof that anyone could do anything if they set their mind to it.

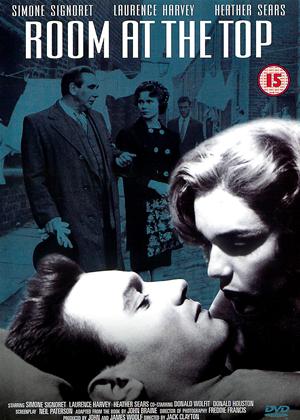

In a way, they were following in the footsteps of the 'angry young men' who had populated such social realist dramas as Jack Clayton's Room At the Top (1958), Tony Richardson's Look Back in Anger (1959), and Karel Reisz's Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960). But they had more in common with the irreverence of Tom Courtenay's character in John Schlesinger's Billy Liar (1963), which had been adapted from a 1959 novel by Keith Waterhouse. Consequently, The Beatles wanted nothing to do with the kind of film musical that Cinema Paradiso users will know from Elvis Presley on Screen and The Golden Age of British Pop Musicals. They wanted to do it their way and, in the process, they made themselves even famous and transformed the relationship between rock music and film.

They're Gonna Put Us in the Movies

The Beatles weren't the first Merseybeat band to make a movie. In late 1963, The Searchers guested in Robert Hartford-Davis's Saturday Night Out, which reached UK cinemas in April 1964, as The Fab Four were finishing their final scenes. Offers for John, Paul, George, and Ringo to appear on the big screen had started to come in as early as February 1963, before they had released their first LP or topped the singles charts. In April, Giorgio Gomelsky spoke to manager Brian Epstein about his charges gracing an experimental short by Ronan O'Rahilly, the Irishman whose exploits with the pirate station, Radio Caroline, were fictionalised by Richard Curtis in The Boat That Rocked (2009).

This project never got beyond a vague outline, but Epstein refused to consider the enquiries made by Michael Winner, in spite of the fact he had just directed another Scouse musical star, Billy Fury, in Play It Cool (1963). Epstein was more cautiously receptive to Hartford-Davis's request for The Beatles to perform a couple of numbers in his teenage morality saga, The Yellow Teddy Bears (1963), which was alternatively known as Gutter Girls and The Thrill Seekers. As the director insisted on the Mop Tops playing songs he had written, Lennon and McCartney nixed the idea and the gig went to The Embers, a band hastily recruited by guitarist Malcolm Mitchell.

By this time, The Fabs had reached cinemas via a Pathé News piece entitled, 'The Beatles Come to Town', which showed an audience at the ABC Cinema in Manchester going potty to 'She Loves You' and 'Twist and Shout'. The crowd at the Coliseum in Washington, D.C. proved just as noisy on 11 February 1964, when a 12-song set was recorded for cinematic consumption after the success of the quartet's first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. Cinema Paradiso users can relive this particular slice of history in The Beatles: The Four Historic Ed Sullivan Shows (2003). But the full impact of this first landing by the 'British Invasion' can be seen in Robert Beyer's The Beatles: Meet The Beatles (1964) and Ron Howard's The Beatles: Eight Days a Week: The Touring Years (2016). The latter makes use of the cinéma vérité footage taken by David and Albert Maysles for the Granada news report, 'Yeah! Yeah! Yeah! New York Meets The Beatles', which they incorporated into What's Happening: The Beatles in the U.S.A. (1964), which was re-edited for the 1990 reissue, The Beatles: The First U.S. Visit.

Witnessing the impact of Beatlemania on Britain in August 1963, Noel Rogers, the head of UA Music (the music publishing arm of the United Artists company that had been set up by Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, and D.W. Griffith in 1919) noticed that there was a loophole in the contracts that Epstein had signed with the Parlophone and Capitol record labels. These arrangements didn't cover film soundtracks and Rogers realised that a tidy profit could be made. The idea appealed to George 'Bud' Ornstein, UA's European production chief, who had already tasted success in the UK with Terence Young's Dr No (1962) and Tony Richardson's Tom Jones (1963), which would go on to win the Academy Award for Best Picture. As UA distributed rather than produced films, Ornstein needed a partner and reached out to Walter Shenson, an American in London, who had scored hits with Jack Arnold's The Mouse That Roared (1959) and its sequel, The Mouse on the Moon (1963).

Shenson set up Proscenium Films to co-ordinate the production and cut deals with Epstein's NEMS company and the band's music publishers, Northern Songs. However, he had still to meet his stars and did so on a chaotic black cab ride to Abbey Road Studios, where The Beatles were due to watch producer George Martin record a track with their stablemates, Gerry and The Pacemakers. On 16 October 1963, John, George, Paul, and Ringo broke off rehearsals for a BBC radio show to meet the director of The Mouse on the Moon, Richard Lester, who was already well known to them from his other credentials (as we shall see below).

As a graduate of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, Epstein was so excited by the prospect of The Beatles being signed by a Hollywood studio that he agreed to a three picture deal with UA on 29 October. In his eagerness, however, he only asked for a £20,000 advance and 7.5% of the profits, with the remainder to be split between Shenson and UA. They determined a £180,000 budget for a black-and-white feature that would showcase six new Lennon-McCartney songs. The shoot would last for six weeks in the spring of 1964 and Lester would receive £6000 and a 1% share for his efforts. He was so keen to work with The Fab Four that he signed up immediately and went in search of an idea.

Goon With the Wind

Richard Lester was born in Philadelphia in January 1932. He was still a teenager when he started directing for television and was only 23 when he fetched up in London. Among the shows he worked on was The Vise (aka Saber of London; 1955-57), episodes of which can be seen on The Best of Classic British TV Crime Series (2009). But it was the calamitous first and only night of The Dick Lester Show (1955) that prompted a phone call from Peter Sellers.

Along with Spike Milligan and Harry Secombe, Sellers had found fame on BBC radio in The Goon Show (1951-60). Indeed, they had just recorded a parody of 'Unchained Melody' at EMI's Abbey Road Studios with a certain George Martin. As the trio was about to move into television, they recruited Lester to work on The Idiot Weekly, Price 2d, A Show Called Fred, and Son of Fred (all 1956). Various Goon members had ventured into films via Anthony Young's Penny Points to Paradise (1951), Maclean Rogers's Down Among the Z Men (1952), and Joseph Sterling's The Case of the Mukkinese Battle-Horn (1956), which Cinema Paradso users can find on The Renown Comedy Collection: Vol.2 (2017). But the pick of their excursions was Lester's 'The Running Jumping & Standing Still Film' (1959), a madcap Sellers/Milligan vehicle that was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Live-Action Short.

Available from Cinema Paradiso on The Lacey Rituals (2012), this cockeyed romp filmed on consecutive Sundays on a 16mm Bolex became a firm favourite of Lennon, McCartney, and Harrison when they caught it at the Tatler News Theatre on Church Street between sessions at The Cavern Club in nearby Mathew Street. They might even have seen Lester's 1959 short, Have Jazz Will Travel (aka The Sound of Jazz), as well as his feature bow, It's Trad, Dad! (aka Ring-a-Ding Rhythm, 1962), although they would have been more interested in Gene Vincent, Del Shannon, Helen Shapiro, Chubby Checker, and Gary U.S. Bonds than jazzmen like Acker Bilk, Chris Barber, and Kenny Ball. But, as with George Martin, it was Lester's Goon connection that won The Beatles over, as they sought to break the mould of the pop musical.

A Hard Day's Write

Walter Shenson agreed with The Fab Four that they should avoid playing fictional characters like Elvis and Cliff and stick to variations of themselves. Consequently, it was agreed that the yet untitled film would be a 'fictionalised documentary'. Dick Lester was keen to hire Johnny Speight to produce the screenplay on the strength of his work on The Arthur Haynes Show (1956-66). He would go on to script the controversial sitcom, Till Death Us Do Part (1965-75), which starred Warren Mitchell as the bigoted Alf Garnett. But Speight was otherwise occupied and so were Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, who had enough on their plates with Steptoe and Son (1962-74), a sitcom about father-son rag-and-bone men (Wilfrid Brambell and Harry H. Corbett) that they had devised after parting ways with Tony Hancock after almost a decade of radio and television success.

Even though John Lennon joked that he was a 'professional Liverpudlian', the group preferred Welsh-born writer, Alun Owen, who had proved his Scouse credentials with the 1959 Armchair Theatre episode, 'No Trams to Lime Street'. Owen has also scripted Joseph Losey's The Criminal (1960), for which Lester had composed a score that was rejected in favour of one by Johnny Dankworth. Moreover, Owen had acted in four of Lester's TV shows, but he only became free after delays prevented the West End opening of Lionel Bart's Liverpudlian musical, Maggie May.

Rejecting a speculative proposal that The Fabs should travel around in a van filled with 007-style gizmos, Lester took his cue for the scenario from Lennon's description a recent tour to Sweden: 'It was a room and a car and a room and a concert and we had cheese sandwiches sent up to the hotel room.'

Consequently, Owen was sent to Dublin to watch The Beatles give two shows at the Adelphi Theatre in Dublin in November 1963. As Owen reflected in the 50th anniversary documentary, 'You Can't Do That' (2014), which is among the extras on the DVD and Blu-ray available from Cinema Paradiso: 'At no time were they allowed to enjoy what was supposed to be success...the only freedom they ever actually get, is when they start to play the music and then their faces light up and they're happy.'

Although Lester thought Owen's first script was along the right lines, he felt it was wordy and awkward in its song transitions. While Owen returned to the drawing board, Lester went to see The Beatles Christmas Show at the Astoria Theatre in Finsbury Park to gauge how they coped with the sketches that helped pad out the musical programme. He also suggested that he, Owen, and Shenson should accompany the boys to Paris in January 1964, so they could sample for themselves the claustrophobic chaos of life on tour.

After being in close proximity for a few days, Lester decided that the Mop Tops shared so many character traits that it was difficult to distinguish them. So, he told Owen to make John subversive and sarcastic, Paul sweet and focussed, and George sullen and detached, while Ringo would be depicted as the outsider, even though he had now been a Beatle for 18 months.

Lester also insisted that the foursome showed no deference to the toffs who viewed them as inferior curios or the media and business bods who sought to box and exploit them for their own ends. United against the world, The Beatles were to embody the notion that anyone could do anything, regardless of breeding, wealth, or education. Lester believed they were socio-cultural revolutionaries and he wanted everyone else to know. Hence, there was no room for internecine conflict or love interests.

Owen was distinctly unchuffed that only the opening train sequence remained from his first draft. But, at Lester's behest, he quickened the pace, sharpened the storyline, and introduced more visual humour. Events across the Atlantic shifted the dial, however, as a nation still mourning President John F. Kennedy saw hope for a brighter tomorrow while watching four youngsters from Liverpool on The Ed Sullivan Show in February 1964. Overnight, The Beatles became the most famous people in the Western world and UA was so afraid of losing them to a rival studio that it upped their salary to £25,000 and their profit cut to 20%. Now all they had to do was act naturally.

All Together Now

Knowing he would be shooting in an unconventional manner to a tight schedule, Lester reunited with cinematographer Gilbert Taylor from It's Trad, Dad!, who was placed in charge of a team of six operators, who used handheld Arriflex cameras to provide plentiful coverage of each scene and remove the onus on The Beatles of having to hit their marks, while giving them the freedom to play takes in different ways. Aware that he would also need to edit during the shoot to make deadlines, Lester also recruited veteran editor John Jympson, who had just finished working on Cy Endfield's Zulu. Taylor had just completed Stanley Kubrick's Dr Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (both 1964), so a small monochrome musical was going to seem like a busman's holiday.

Exhausted after supervising Jack Cardiff's The Long Ships (1964) in Yugoslavia, Denis O'Dell turned down the chance to become associate producer. But his teenage children bullied him into taking up the role and, having saved the production a fortune with his wheeler-dealing, he became a key member of the Beatle entourage. Indeed, he would merit a mention in 'You Know My Name (Look Up the Number) ', while Wilfrid Brambell would take time off from Steptoe and Son to record 'Time Marches On' in 1971 to mark the break-up of the Fab Four, with whom he had co-starred as Paul's grandfather, John McCartney, after Lester had campaigned for Dermot Kelly, the Irish actor familiar from The Arthur Haynes Show. Fellow Scouser Norman Rossington was cast as Norm, the band's manager (who owed more to road manager Neil Aspinall than Brian Epstein), while writer John Junkin was a late choice for Shake, the assistant who was vaguely modelled on trusted roadie, Mal Evans.

Welshman Victor Spinetti was chosen to play the TV director, who Lester and Owen had based on erstwhile colleague Philip Saville, who would go on to win a BAFTA for another Scouse classic, Boys From the Black Stuff (1982). Spinetti would become a Beatle regular, with the admiration being mutual, as he wrote in his autobiography: 'between takes, The Beatles didn't go to their dressing room like film stars. They sat behind the set, chatting away. I've made lots of films but I've only worked with two other people like that, Richard Burton and Orson Welles. Richard recited poetry while Orson told stories.'

Shooting started on 2 March 1964 with the dining car scene on a special train running between London Paddington and Minehead, which was hired for £600 a day. Thanks to Smith's crisps, George got to meet future wife Pattie Boyd, who had been cast as one of the schoolgirls after Lester had directed her in a commercial. Next up, character stalwart Richard Vernon played the stuffy commuter whose older generation disdain at the quartet's presence in his compartment is debunked with irreverent glee and a touch of surrealism, as The Fabs are seen running alongside the train to ask for their ball back.

Lester exploited the cramped conditions to reinforce the sense of a shut-in existence. But the need to keep the cameras close meant that their motors could be picked up by the microphone and the dialogue had to be dubbed. The luggage van sequence was done at Twickenham Studios to make it easier to get close-ups of the boys playing cards and singing 'I Should Have Known Bettter' inside a cage that confirmed their captivity. The hotel room scenes were also filmed here, as were the canteen and dressing-room sequences. Fab fans will recognise the man whose tape measure gets snipped by John as Dougie Millings, the tailor who had created the famous collarless suits that had helped transform the band's image from leather-clad rockers.

Twickenham corridors provided the settings for Brambell's brush with Derek Nimmo's dove magician and Lennon's mistaken identity exchange with Anna Quayle. The police station in which Ringo and Brambell are detained was mocked up at the studio late in the shoot, as was the office of the trend-setting producer (Kenneth Haigh) who is offended by George mocking some 'grotty' shirts and the 'posh bird' who presents his weekly show. Also filmed late in the day was the washroom scene, in which George shaves a foam beard sprayed on the mirror and John plays with some boats in a bubble bath.

As Lester had to work around location availability and the busy Beatle schedule, the next scenes to be shot made use of a helicopter at Gatwick Airport. A run-down camera battery taking aerial shots of The Beatles larking around on the tarmac left Lester with some speeded-up footage. But this proved to be a happy accident, as he undercranked the great escape shenigans while shooting at Thornbury Playing Fields in Isleworth, in order to give the imagery a madcap energy.

Several other flubs made the final cut, including George and Ringo tripping over during the opening flight from the pursuing fans and George knocking over his amplifier during 'If I Fell', as Lester felt they enhanced the sense of docu-authenticity. To this end, he also shot directly into a spotlight while seated on a swing to achieve a circular track around Paul singing 'And I Love Her'. This was one of many stylistic choices that owed much to the French New Wave, although the suits at UA thought such flaring was highly unprofessional.

These numbers formed part of the rehearsal sequence, which was filmed at the Scala Theatre, which had been made over to resemble a television studio. When the police forbade the picture to shoot on the streets outside, Lester used the dress circle lounge to improvise the press conference that sees The Beatles answering banal questions with their trademark Scouse insouciance. Although they had four days off for Easter, they had to juggle sessions for the soundtrack album with picking up their Variety Club Awards from Prime Minister Harold Wilson and recording slots for Top of the Pops and Ready, Steady, Go!, as well as the ITV special, Around The Beatles. John also had to leave Isleworth early on 23 April to attend a Foyle's literary luncheon after publishing In His Own Write, which Spinetti adapted for the National Theatre as Scene Three Act One. Whatever happened to the music composed for the show by Lennon and George Martin?

With life imitating art, The Beatles felt at home on the set. As they were accustomed to lip-synching for the telly, the musical scenes were a doddle. But Lester went to town in capturing 'Tell Me Why', 'And I Love Her', 'I Should Have Known Better', 'If I Fell', and 'She Loves You' for the 17-minute concert sequence, as his seven cameras exposed 27,000ft of film. Three cameras focussed on the screaming fans, who included a 13 year-old Phil Collins, who would go on to find fame as the drummer of Genesis.

Although this provided the grand finale, there was still much to shoot. Two Sundays were spent filming the opening scene at Marylebone Station, which was the only London terminus to have a day of rest. This was accompanied by 'A Hard Day's Night', which Lennon and McCartney had composed overnight on 15 April after Shenson had badgered them about the film's title after no one had really liked Moving On, Let's Go, Travelling On, and (John's suggestion) Oh! What a Lovely Wart. Lennon claimed that 'a hard day's night' was a classic Ringoism, although it had already featured in the 'Sad Michael' story in his book.

Two scenes were shot at Les Ambassadeurs, an exclusive club near Hyde Park that had also featured in Dr No. In addition to standing if for Le Circle Club, the venue also hosted the nightclub scene, which featured an uncredited Charlotte Rampling among those dancing to 'I Wanna Be Your Man' and 'Don't Bother Me', tracks from the With The Beatles album that meant Ringo and George got to make vocal contributions to the soundtrack.

Having shot the fire escape scramble at the Odeon Cinema in Hammersmith, Lester devoted the last few days to Ringo's riverside perambulations. He had already filmed at the Turk's Head pub in Twickenham, but relocated to Kew for the encounter between Ringo (who was suffering from a hangover) and truanting schoolboy, David Jaxon. On the last day of shooting, Lester went to Ealing for Ringo's Walter Raleigh act, which culminates in a sight gag that was born of the director's love of the slapstick classics of Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Laurel and Hardy.

A wrap party followed, but the band was still on call. On 29 April, they went to view their waxworks at Madame Tussaud's for a BBC documentary, Follow The Beatles, which also covered the making of the film through interviews with the cast and crew. All agreed that it had been an enjoyable experience, although Lennon would later grumble that A Hard Day's Night was 'a comic-strip version of what was actually going on. The pressure was far heavier than that.'

You Can't Do That

Lester had gone out of his way to make the shoot as stress-free as possible by encouraging The Beatles to make suggestions on set and even filming rehearsals in case somebody came up with an unscripted gem. He also kept them away from the daily rushes to prevent the inexperienced actors from getting self-conscious about their performances. After a couple of weeks, however, the Liverpudlians began wondering why the director kept disappearing for a couple of hours each day and they followed him to the screening room. Asking if they could come along, they soon found seeing the previous day's scenes to be really useful, especially when it came to supporting each other through rough patches.

Lennon later revealed, 'The best bits are when you don't have to speak and you just run about. All of us like the bit in the field where we jump about like lunatics because that's pure film, as the director tells us; we could have been anybody.' While Ringo took most of the plaudits, Lester believed that Harrison was the most natural on camera. 'The most accomplished actor is George.' he said. 'He never attempted too much or too little. He was always right in the centre. He got out of the scene everything there was to get out of it. There wasn't a lot for him to do, but what there was he had to do, he did well.'

As he was dating actress Jane Asher, Paul was particularly eager to impress. However, Lester believed he kept trying too hard and delayed shooting his solo set-piece in the hope that he would become more relaxed when delivering his lines. Despite several rewrites and retakes, however, the scene between McCartney and Isla Blair, as an actress in Restoration costume, simply refused to come together. As a result, it was dropped and, because UA insisted on destroying off-cuts at the end of the project, it was lost forever.

Lester also cut some of Brambell's scenes, as he felt he was trying to steal focus. His flirtation with a wealthy widow on the train was cut to a punchline, while his contretemps with a juggler on the variety show was dropped. The gag with him popping up through a trap door in the middle of an operatic aria was retained, however, as was a running joke about him being quite clean in comparison to Old Man Steptoe. A traffic jam sequence was also lost to posterity, along with a fight over Ringo's drums before 'If I Fell'. As the concert sequence was already pretty lengthy, 'You Can't Do That' was snipped, although the footage survived and featured in the 2014 documentary of the same name, hosted by Phil Collins.

According to some eyewitnesses, Lester also shot a scene in Liverpool, in which George drives Paul and John round to Ringo's home in Admiral Grove to collect him. No mention is made of the excursion in the schedule, however, although a similar scene would surface in George Dunning's Yellow Submarine (1968), although Lester abandoned his own attempt at an animated sequence involving the band and Lionel Blair's dance troupe, as it proved too time-consuming to film. Rapid editing achieved a stop-motion effect during the innovative closing credits, however, as Jympson made snappy use of the portraits that Lennon's Emperor's Gate neighbour, Robert Freeman, had taken for the Parlophone album cover.

Recognising that they were working to a strict deadline, Lester and Jympson edited during the shoot. They cut the songs to the rhythm of the music, but discarded the rulebook for the remainder of the action, with matchlines being ignored and jump cuts being inserted to match the rascally zest of The Fabs. It was all very nouvelle vague and Shenson was concerned that fans wouldn't understand the modish style. Indeed, he feared he had an 87-minute flop on his hands and was immensely relieved when UA executives declared it a triumph. Someone did suggest dubbing the Scouse accents for the US version, but McCartney testily pointed out: 'Look, if we can understand a f***in' cowboy talking Texan, they can understand us talking Liverpool.'

And in the end...

On Monday 6 July 1964, Shaftesbury Avenue in London's West End came to a standstill. The day before, Tony Richardson's Oscar-winning Tom Jones had played to its last house at The London Pavilion without undue fuss. But 12,000 teenage fans shrieked at the sight of the car bringing The Beatles to the charity world premiere of A Hard Day's Night. Sporting matching tuxedos with velvet collars, they got out to see a neon billboard proclaiming: 'The Beatles in Their First Full-Length, Hilarious, Action-Packed Film and 12 Smash Song Hits.'

The Fab Four had seen the finished film a couple of days earlier. Lester had ducked the preview and Shenson was unnerved by the silence as the lights went up. Eventually, George said, 'Well I liked it. I think it's very good,' and the other three concurred. Now, they were going to see it again, along with a short travelogue about New Zealand, in the presence of Princess Margaret, Lord Snowden, and an audience who had paid £16 a ticket for the privilege. Fortunately, the reception was tumultuous and the relieved quartet left an after-party at the Dorchester Hotel in Park Lane for The Ad-Club to join Rolling Stones Keith Richards, Brian Jones, and Bill Wyman in a hard night's drinking.

Four days later, a plane touched down at Speke Airport (which has since been named after John Lennon), where a crowd of between 1500 and 3000 screaming fans reassured the Mop Tops that Liverpool had not turned its back on them for relocating to That London. They had come home for the Northern Premiere and were met by a press pack similar to the one in the film. When John was asked what he thought of their debut, he joked 'Not as good as James Bond though, is it?' When quizzed about future projects, he replied, 'Don't know. I'd like to make more films, I think. We'd all like to do that, 'cos it's good fun, you know. It's hard work, but you can have a good laugh in films.' One reporter tackled George with the question, 'You fancy yourselves as actors then, do you?' He responded: 'No, definitely not. We enjoyed making the film, and especially the director was great, you see, and it made it much easier for us. None of us rate ourselves as actors, but, as you know, it's a good laugh and we enjoy doing it. So we'd like to make a couple more.'

Eight police outriders escorted the convoy of cars over the 10-mile route to the city centre, which was reportedly lined by around 200,000 people. A crowd of 20,000 squeezed into the square in front of Liverpool Town Hall and they were rewarded with a glimpse of the local boys made good when they arrived around 7pm. After a break for dinner, during which the group received a request for signed photographs from Queen Elizabeth II, The Beatles went out on to the balcony to greet the adoring throng, as the police brass band played 'Can't Buy Me Love'. Back inside, a select band of 700 dignitaries and family members watched Mayor Louis Caplan give The Beatles the keys to their city.

Having donated a celebration cake to the Alder Hey Children's Hospital, the foursome made the short trip from Castle Street to The Odeon on London Road. Another press conference preceded the premiere before The Fabs were whisked away, albeit not to a midnight matinee in Wolverhampton. They wouldn't return to Merseyside until November and played only one more concert on their old stomping ground, in December 1965, by which time they had reunited with Lester to make Help! (1965). Fun though it was (and in colour, too), this globe-trotting escapade was much less feted than its predecessor, which had been released on 1500 prints worldwide. It grossed $22 million (£14 million), with only Guy Hamilton's Goldfinger and Zulu beating it in the end-of-year box-office charts. Moreover, it drew positive reviews from old guard critics who had admitted to disliking pop music. Doyenne Dilys Powell dubbed the stars 'the Sacred Four', while The Hollywood Reporter congratulated 'the Liverpool string quartet'. But Arthur Knight was more enthusiastic when comparing their comic rapport with the four Marx Brothers and The Three Stooges in The Saturday Review.

The latter notice would have thrilled Lester, who was also gratified by reviewers who had spotted his homages to Jean-Luc Godard's À bout de souffle (1960) and François Truffaut's Jules et Jim (1962). But nothing topped Andrew Sarris's contention in The Village Voice that A Hard Day's Night was 'the Citizen Kane of jukebox musicals'. In addition to inventing the use of needle drops on film soundtracks, Lester also revolutionised the way in which pop music was filmed and he has widely been acknowledged as the godfather of the music video - although the best promos for Beatle hits were directed by Joseph McGrath and Michael Lindsay-Hogg, as can be seen on The Beatles: No.1 (2015).

The film's reputation was further boosted when Alun Owen and George Martin respectively received Oscar nominations for Best Original Screenplay and Best Scoring of Music. The Beatles landed BAFTA nods in the Best Newcomer category, while they won Grammys for Best New Artist and Best Group Vocal Performance for the title track.

As Cinema Paradiso members might recall, we looked at John, George, Ringo, and Paul's later screen excursions in The Beatles in Film, the sixth of the now 325+ articles in the Collections series. After Help!, they made The Magical Mystery Tour (1967) in the aftermath of the accidental drug death of Brian Epstein. Shenson tried to tempt the group with The Three Musketeers and Richard Condon's A Talent For Loving, while playwright Joe Orton submitted Up Against It, as Stephen Frears revealed in Prick Up Your Ears (1987). O'Dell even suggested The Lord of the Rings with Stanley Kubrick directing Paul as Frodo, Ringo as Sam, George as Gandalf, and John as Gollum. However, J.R.R. Tolkien, who detested pop music, refused to contemplate the idea. Ironically, Peter Jackson, who successfully brought 'The Lord of the Rings' (2001, 2002 and 2003) and 'The Hobbit' (2012, 2013 and 2014) to cinema screens, supervised the restoration of Michael Lindsay-Hogg's Let It Be (1970) footage to create the masterly documentary, The Beatles: Get Back (2021).

Having regained control of the rights to A Hard Day's Night, Shenson decided to remix the soundtrack in Dolby and append a photomontage prologue cut to 'I'll Cry Instead'. He delayed the release of his new version until 1982 in order to avoid accusations of cashing in on John Lennon's murder in December 1980. But Lester was dismayed by the change and celebrated its removal when Shenson sponsored a restoration in 1999. Lester appeared in the 2002 'making of' short, Things They Said Today, which isn't currently available on a UK disc. But it will be clear to anyone renting A Hard Day's Night from Cinema Paradiso, as it turns 60, that it has lost none of its freshness, wit, zing, and style over the intervening years on which it has exerted an incalculable influence. The music isn't bad, either, right down to the George Martin-scored instrumentals played by Vic Flick, the guitarist who also twanged the theme to TV's Juke Box Jury and John Barry's arrangement of 'The James Bond Theme' that was still in use on Cary Joji Fukunaga's No Time to Die (2021) and will be again when EON finally decides who will become 007 after Daniel Craig, who started acting at the Everyman Theatre in Liverpool, where, 50 years ago, Willy Russell premiered the wonderful and unfairly forgotten John, Paul, George, Ringo...and Bert (1974). Surely, it's time for someone to commit this landmark musical to disc?

-

Anatomy of a Murder (1959)

Play trailer2h 34minPlay trailer2h 34min

Play trailer2h 34minPlay trailer2h 34minPaul McCartney's grandfather (Wilfrid Brambell) tells Ringo Starr that he should be out 'parading' instead of sitting in a canteen with his hooter in a book. The tome in question is a thriller written by John D. Voelker under the name Robert Traver, which was adapted by Otto Preminger into this tense and daringly graphic courtroom drama starring James Stewart and Lee Remick, which did much to dent the Production Code.

- Director:

- Otto Preminger

- Cast:

- James Stewart, Lee Remick, Ben Gazzara

- Genre:

- Thrillers, Drama, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

French Dressing (1964)

1h 23min1h 23minOliver Hardy wasn't the first to fall into a big hole filled with water in James W. Horne's Way Out West (1937) and he certainly wasn't the last. The gag was dusted down for Ringo in A Hard Day's Night. But Ken Russell also used it in 1964, as French film star Françoise Fayol (Marisa Mell) gets a soaking while visiting the seaside resort of Gormleigh.

- Director:

- Ken Russell

- Cast:

- James Booth, Roy Kinnear, Marisa Mell

- Genre:

- Comedy, Classics, Drama

- Formats:

-

-

Catch Us If You Can (1965) aka: Having a Wild Weekend

1h 27min1h 27min

1h 27min1h 27minOf British Invasion acts, only The Dave Clark Five made more appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show than The Beatles. They play stuntmen-cum-extras on the lam in John Boorman's freewheeling romp, which was released Stateside as Having a Wild Weekend. Marianne Faithfull turned down the Barbara Ferris role.

- Director:

- John Boorman

- Cast:

- Dave Clark, The Dave Clark Five, Barbara Ferris

- Genre:

- Comedy, Classics, Music & Musicals

- Formats:

-

-

The Knack and How to Get It (1965) aka: The Knack... and How to Get It

Play trailer1h 22minPlay trailer1h 22min

Play trailer1h 22minPlay trailer1h 22minRichard Lester continued to capture the Swinging Sixties vibe in this rite of sexual passage, which was adapted from an Ann Jellicoe play by Charles Wood. Charlotte Rampling and Jane Birkin have bit parts, as bashful schoolteacher Colin (Michael Crawford) asks womanising roommate Tolen (Ray Brooks) for tips on chatting up girls. Winner of the Palme d'or at Cannes, this emblematic comedy also earned Liverpudlian Rita Tushingham a Golden Globe nomination.

- Director:

- Richard Lester

- Cast:

- Rita Tushingham, Ray Brooks, Michael Crawford

- Genre:

- Classics, Comedy, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

The Beatles: Help! (1965)

Play trailer1h 36minPlay trailer1h 36min

Play trailer1h 36minPlay trailer1h 36minThe Fabs pop up in the Alps and the Bahamas, as a cult tries to recover a sacrificial ring that has found its way on to Ringo's finger. John Lennon complained that the group were extras in their own film, which has dated somewhat, thanks to Leo McKern playing an Indian in brownface. But the songs are superb and George Harrison has a cracking gag in the end credits.

- Director:

- Richard Lester

- Cast:

- John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison

- Genre:

- Comedy, Music & Musicals, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

How I Won the War (1967)

1h 46min1h 46min

1h 46min1h 46minLennon joined Lester in Almeria for this adaptation of a Patrick Ryan novel about a Second World War mission to defy the enemy and lay a cricket pitch. Michael Crawford stars as the hapless Lieutenant Earnest Goodbody, with Lennon (in his only non-musical role) as the quick-witted Private Gripweed. David Trueba's Goya-winning Living Is Easy With Eyes Closed (2013) is set against the film's Spanish shoot and really should be on disc in the UK.

- Director:

- Richard Lester

- Cast:

- Michael Crawford, John Lennon, Roy Kinnear

- Genre:

- Classics, Comedy, Action & Adventure

- Formats:

-

-

Petulia (1968)

Play trailer1h 41minPlay trailer1h 41min

Play trailer1h 41minPlay trailer1h 41minJohn Haase's Me and the Arch Kook Petulia provided the inspiration for Lester's first feature on home soil, which was co-produced by Denis O'Dell. Julie Christie takes the lead as an unhappy San Franciscan wife who cheats on abusive husband Richard Chamberlain with older doctor, George C. Scott. It's a zeitgeisty piece, with a John Barry score and songs by The Grateful Dead and Big Brother and the Holding Company. The penguins at the aquarium, by the way, are called George and Ringo.

- Director:

- Richard Lester

- Cast:

- Julie Christie, George C. Scott, Richard Chamberlain

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

Steptoe and Son / Steptoe and Son Ride Again (1973)

3h 8min3h 8min

3h 8min3h 8minAfter a decade on the Beeb, Albert (Wilfrid Brambell) and Harold Steptoe (Harry H. Corbett) made it on to the big screen in Cliff Owen's spin-off feature. The plot revolves around Albert's resentment at Harold marrying Zita (Carolyn Seymour), a stripper he had met at a stag do. The pathos outweighs the humour in a touching saga that would be followed by Peter Sykes's Steptoe and Son Ride Again (1974), in which the duo acquire a greyhound.

- Director:

- Cliff Owen

- Cast:

- Mike Reid, Yootha Joyce, Wilfrid Brambell

- Genre:

- Comedy, Classics, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

The Rutles: All You Need Is Cash (1978)

1h 13min1h 13min

1h 13min1h 13minOh, the genius of Eric Idle's Beatle parody, as The Rutles feature in the movies A Hard Day's Rut, Ouch!, Yellow Submarine Sandwich, and Let It Rot. Neil Innes's pastiche tunes are impeccable, as is his performance as Ron Nasty, alongside Idle's Dirk McQuigley, Ricky Fataar's Stig O'Hara, and John Halsey as Barry Wom. George Harrison cameos as a news reporter.

- Director:

- Eric Idle

- Cast:

- John Halsey, Ricky Fataar, Neil Innes

- Genre:

- Comedy, Music & Musicals, Documentary, Special Interest

- Formats:

-

-

The Beatles: Get Back (2021)

7h 48min7h 48min

7h 48min7h 48minA small corner of Twickenham Studios is seen in all its gloomy glory in Peter Jackson's epic revisitation of the Let It Be sessions from January 1969. Ringo was about to co-star on the lot with Peter Sellers in Joseph McGrath's The Magic Christian, so tempers and deadlines were strained after George quit the band, leaving Paul and John to have a heart-to-heart over a canteen vase that just happened to contain a microphone. A masterclass in film restoration, this is a must-see for all Fabs fans.

- Director:

- Peter Jackson

- Cast:

- The Beatles, John Lennon, Paul McCartney

- Genre:

- Documentary, Music & Musicals, Children & Family, Performing Arts, Special Interest

- Formats:

-