As Picnic At Hanging Rock celebrates its 50th anniversary by returning to UK cinemas in a 4K restoration, Cinema Paradiso goes behind the scenes of a mystery without a solution that has lost none of its power to beguile, intrigue, and unsettle.

Australia was a cinematic backwater in the early 1970s. As Mark Hartley reveals in Not Quite Hollywood (2008), a handful of 'ocker' comedies like The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (1972) had scored with domestic audiences, but they had done little business abroad. Everything changed with Peter Weir's Picnic At Hanging Rock (1975), a period drama that took the bold step of presenting a mystery without a solution.

Hartley had covered the making of the film in the 2004 documentary, A Dream Within a Dream. But none of the talking heads speaks directly about the major themes of the film: the legacy of Empire, forced Indigenous dispossession, female sexuality, child abuse, and the tremor of violence that seethes below the surface of a costume drama set in the last year of Queen Victoria's reign. This was also the year before Australia became a confederated commonwealth, which makes this a coming of age picture on several levels.

A Labour of Lovell

Novelist Joan Lindsay always claimed that elements of her 1967 Gothic tome, Picnic At Hanging Rock were true. There was a recorded incident of some white girls going missing in the Bush, but this had occurred a century before the events depicted in the book. Lindsay had attended a school similar to Appleyard College, so perhaps, when she claimed veracity, she was referring to the overall atmosphere, the relationships between the students, or the strictness of the regime imposed by the headmistress?

Whatever the truths of the story, they fascinated television personality Pamela Lovell when she read the novel and became instantly convinced it would make a great film. Lovell presented the Today programme and a number of shows for younger viewers, but had no experience of film production. Indeed, she hadn't even secured the rights to the text when, in 1972, she showed it to Peter Weir, whose credits at the time were limited to the 'Michael' segment of the anthology, 3 to Go, and the bleak satire, Homesdale (both 1971).

Lowell approached Weir because she felt he would be able to capture the unsettling sense of mystery that she wanted to convey. While he was taken by the book, Weir was about to embark upon The Cars That Ate Paris (1974) and said he would be too busy. But the story kept haunting him and he contacted Lovell to say he would like to make the film after all. However, she was having trouble raising funding, as the nascent Australian cinema was very much a boys club. So, having been turned down by the Australian Film Development Corporation, Lovell worked for free on Bruce Beresford's TV documentary, Monster or Miracle: Sydney Opera House (1973), in order to get a credit that might improve her standing with potential backers.

On making a second application to the AFDC, Lovell was told that the project was too risky. However, she discovered that the commission had just agreed to bankroll a story that bore a suspicious similarity to Lindsay's novel and Lovell received funding of 1500 AUD after she threatened to inform Lindsay's publishers of the suspected plagiarism.

Realising that Lovell needed a little support, Weir introduced her to producer twins, Hal and Jim McElroy, with whom had made The Cars That Ate Paris. She was grateful for their nous, but was concerned that they wanted to take things down the Ozploitation route by emphasising the innocent sensuality of the schoolgirls and adding a lesbian love story. However, she stuck to her guns and refused to change the second draft of the screenplay that Cliff Green had produced after he had been recommended to Lovell by her first choice, playwright David Williamson.

Feeling that Lovell was the stumbling block to securing a budget, the McElroys tried to talk her into stepping down. However, Lindsay (who had already turned down several approaches to adapt her book) insisted on working with Lovell and Weir after they had visited her home. Lovell had optioned the rights with100 AUD from her savings and would go on to rack up 11,000 AUD of debt to ensure the film was made on her own terms. She finally persuaded the AFDC to bankroll her vision of the story. But, in order to coax the McElroys back on board after they had resigned, she had to settle for the credit, 'Produced in association with'.

What's It All About?

A caption reads: 'On Saturday 14th February 1900 a party of schoolgirls from Appleyard College picnicked at Hanging Rock near Mt Macedon in the state of Victoria. During the afternoon several members of the party disappeared without a trace...'

As she wakes, Miranda St Clare (Anne Lambert) can be heard paraphrasing Edgar Allan Poe, as she gazes from her window at Appleyard College:'What we see and what we seem are but a dream - a dream within a dream.' She greets her roommate, Sara Waybourne (Margaret Nelson), who has a crush on her, and tries to cheer her up because she's been excluded from the day's excursion by inviting her to stay with her family on their sheep station. However, Miranda also warns her, 'You must learn to love someone apart from me, Sara. I won't be here for very much longer.'

Elsewhere, the heavy-set Edith Horton (Christine Schuler) counts her Valentine cards (which she has probably sent to herself), as the rest of the girls don their white dresses and black stockings in a state of high excitement, as they are going for a picnic with two of their teachers, Miss Greta McCraw (Vivean Gray) and Mademoiselle de Poitiers (Helen Morse). Gathering on the drive in front of the main steps, the girls are reminded by headmistress Mrs Appleyard (Rachel Roberts) that they are representing the school in the community. However, as it's a warm day, she does give them permission to remove their gloves once their carriage has passed through the nearby town.

En route, driver Ben Hussey (Martin Vaughan) tries to tell the girls about Hanging Rock and is corrected by Miss McGraw, who points out that the formation is a million years old. Lost in wonderment, Irma Leopold (Karen Robson) notes that the rocks have waited all that time just for them. Trundling through the woods, the carriage passes Michael Fitzhubert (Dominic Guard), a young Englishman who is staying with his aunt (Olga Dickie) and uncle (Peter Collingwood). He is glad to have a distraction from a dull picnic lunch and confides his frustration to Albert Crundall (John Jarratt), his uncle's groom, who offers him a consoling swig of beer.

Having cut into a heart-shaped Valentine cake, the girls lounge around in the sun. Miranda studies a flower with a magnifying glass, but she feels restless and asks Mademoiselle if she can go to the foot of Hanging Rock with Irma and Marion Quade (Jane Vallis). Aware he has promised Mrs Appleyard to have the party home in good time, Hussey is concerned by the fact that his watch had stopped at noon. Miss McGraw notices the same thing and puts it down to magnetic forces. She agrees to let the girls go for a short wander and Edith insists on tagging along. As they leave, Mademoiselle looks up from the art book she is reading and declares Miranda to be a Botticelli angel.

Michael is instantly smitten when he sees Miranda picking her way across some stepping stones over a stream. Albert is amused when Michael says he's going to stretch his legs and heads off in the direction of the girls. With Miranda leading, the quartet reaches the foot of Hanging Rock and Edith is dismayed when the others agree to go further because she's already tired. She also can't understand why her companions have removed their shoes and stockings, as they settle for a nap in the sun. When they wake, Miranda leads Irma and Marion into a crevice and Edith gets so scared that she lets out a piercing scream before running back to the group and telling Mademoiselle what has happened.

Miss McCraw goes off in search of the missing girls, as the scene cuts back to the college, where Mrs Appleyard is becoming anxious. She has spent the day browbeating Sara over her failure to learn a poem and warns her that she will be sent back to the orphanage if her sponsor misses another fee payment. Up in her room, Minnie the housemaid (Jacki Weaver) confides to her beau, Tom (Tony Llewellyn-Jones), that Mrs Appleyard is cruel to the girls and that they need a bit of loving rather than discipline.

Darkness has already fallen by the time the carriage returns. But Miranda, Irma, Marion, and Miss McCraw remain unaccounted for and Sergeant Bumpher (Wyn Roberts) is summoned to question the grown-ups, while Doctor McKenzie (John Fegan) reassures Mrs Appleyard that Edith is virgo intacta. But Sara is mortified by the news that her beloved is missing and she confides her misery to Minnie.

Volunteers join Bumpher in scouring the Rock, but there is no sign of the girls or their teacher. Tormented by nightmares and desperately hoping to find Miranda, Michael persuades Albert to ride to Hanging Rock to conduct their own search. He insists on staying overnight and, despite suffering from heat exhaustion, he finds Irma in a nook and Albert races back to town for help. She is placed in an ambulance and, as Michael is about to ride away with her, he hands Albert a small sullied square of white dress material.

Irma is taken to the Fitzherbert mansion to recover, where the maid is puzzled by the fact that the girl's corset is missing. She also claims that Irma had confided that she had seen Miss McCraw running up the Rock in only her bloomers. Puzzled by Edith's report of a red cloud forming over the Rock, Bumpher comes under pressure to find a solution, as the townsfolk are feeling edgy. But he has no tangible evidence and further searches yield no fresh clues. Michael, meanwhile, continues to be troubled by dreams in which Miranda appears as a swan.

As news spreads about the episode, parents decide to withdraw their daughters and Mrs Appleyard is faced with ruin. She allows Irma to say her goodbyes before she sails for Europe, but she is given a tough time by the girls having a dance lesson with Miss Lumley (Kirsty Child) in the gymnasium, where Mademoiselle is horrified to discover that Sara has been lashed to the wall to restrain her on the pretext of improving her posture.

When Mademoiselle asks Mrs Appleyard about Sara over supper, she proves tipsily evasive. But she weeps in her office after telling the girl that she will be sent back to the orphanage when the college breaks for Easter. At the manor, Albert tells Michael that he has been troubled by a dream about his sister (who turns out to be Sara) coming to say goodbye and he mentions her favourite flower just as the school gardener finds her body in the greenhouse after she had jumped from a window and crashed through the roof.

The next morning, Mrs Appleyard lies to Mademoiselle about Sara having departed with her sponsor. When the gardener bursts in to inform her of Sara's suicide, he finds Mrs Appleyard sitting at her desk in mourning dress. The narrator reveals that she was found dead at Hanging Rock shortly afterwards, having seemingly fallen while trying to climb it. Over a hazy flashback to the day of the picnic, the voice divulges that the missing trio were never found and that the mystery long continued to haunt the local community.

Behind the Scenes

Mount Macedon is an extinct volcano of spiritual significance to the Dja Dja Warrung, Taunguring, and the Wurundjeri Woi Warrung peoples. Hanging Rock is considered a dividing point for the tribes and is held in such sacred regard that no one had climbed it for 26,000 years. So, when Irma claims that it had waited a million years just for them, she is summing up the white colonial arrogance that suffuses Peter Weir's film and which is reinforced by its complete and quite conscious lack of an Aboriginal presence.

When Weir and cinematographer Russell Boyd visited the location, they were both struck by its aura. But Boyd (who has only met the director a couple of days earlier) noticed that the light in the picnic spot was only suitable for a couple of hours a day and that the entire location schedule was going to have to be based around noonday excursions to the Rock. 'When we chose the location,' Boyd later remembered, 'I said, "I think we can only shoot for an hour a day here, when the light's just perfect." You see, in the morning, the area was too shadowy from the trees. By late morning, it was perfect, with lots of overhead light. After an hour, it was completely in shadow again because the sun had moved further around. I asked if there was any chance that we could come back every day and continue, one shot at time or two shots at a time? I'm sure they thought I was mad. Actually, I was terrified...I was terrified I was going to get fired off of the movie then and there!'

As Boyd explained in A Dream Within a Dream,'Light played such an incredibly important part in that film. I felt I couldn't manufacture it. I couldn't even try and recreate that beautiful light.' When he came to shooting, Boyd wasn't helped by the fact that one of the two portable generators dropped at the spot by helicopter was damaged and he had to find ways of bouncing sunlight to control the effect.

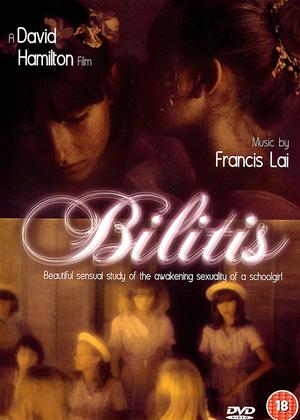

In addition to using reflectors and even parachute silk, Boyd also purchased a length of wedding veil from a Sydney department store and dyed it yellow to intensify the golden nature of the light at the picnic spot. Despite having only previously photographed two films - William Thornhill's Between Wars (1974) and Brian Trenchard-Smith's The Man From Hong Kong (1975) - Boyd had worked on numerous TV documentaries and commercials. He was also an admirer of the way that photographer David Hamilton shaped light in his pictures of young women. Several critics have lamented this influence, as they consider Hamilton's work to be softcore exploitation. But Cinema Paradiso users can judge for themselves through the films that Hamilon later directed: Bilitis (1977), Laura (1979), Tender Cousins (1980), Premiers Desirs, and A Summer in St Tropez (both 1983).

Weir and Boyd had also been influenced by the paintings of Tom Roberts, Charles Condor, Frederick McCubbin, and Arthur Streeton, the Australian Impressionists of the Heidelberg School. It's also tempting to think that some of the blocking of the picnic scene was inspired by William Ford's 1875 canvas, 'At the Hanging Rock', while some have detected the influence of such Pre-Raphaelites as Gabriel Dante Rossetti, Edward Burne-Jones, and John Everett Millais in the framing of the schoolgirls and the way the light catches their hair. Even Bo Widerberg's Elvira Madigan (1967) has been claimed as a forerunner of the soft-lighting effect that Boyd achieved for the picnic scene and which would be endlessly emulated in advertisements, such as the ones for Cadbury's Flake.

An equally important location was Martindale Hall, a Georgian manor near Mintaro, South Australia that had its own unhappy backstory. It had been commissioned by Edward Bowman in an effort to persuade Fanny Hasell to marry him, as she had said that she would only live in a replica of her childhood home. Sadly, she still declined his proposal and Bowman was forced to relinquish the estate (which had its own racecourse, polo ground, and cricket pitch) to pay off his gambling debts. As Martin Sharp, who acted as historical advisor on the film opined, 'You can feel the anguish in the place.'

An expert on the period and Lindsay's novel, Sharp added props to enhance the authenticity of Appleyard College. As Anne Lambert recalled: 'Peter once said Miranda was more of a quality than a character. But the production designer, Martin Sharp, who knew Joan Lindsay and the book well, helped me find her. In my room, for example, if I opened a drawer, it was full of things he'd put there that were meaningful for Miranda: Valentine's cards, handkerchiefs, pressed flowers, photographs in lockets.'

Sharp also collaborated with 25 year-old costume designer, Judith Dorsman, and her assistant Mandy Smith, who had just five weeks to design and sew the entire wardrobe for the staff, students, and locals. He also suggested that Weir alluded to the Indigenous mysticism surrounding Hanging Rock without drawing overt attention to it. But one of his suggestions hit the cutting-room floor, when Weir decided to remove the sequence in which Michael daydreams about a naked Miranda replicating the pose in Botticelli's 'The Birth of Venus'.

Although Weir had initially cast Anne Lambert as Miranda, he had replaced her with Ingrid Mason because he felt she was too knowing to convey the adolescent's innocence. She was certainly more experienced than some of the local Adelaide girls in the cast, after having achieved a degree of fame as Fancy Nancy in a Fanta commercial (which had been shot by Russell Boyd) and because of her roles in the soap, Class of '74, and Peter Benardos's saucy comedy, Number 96 (1974). But she found the recasting hard to take, as she later remembered: 'They offered me the part, but reconsidered and gave it to another actor with very little explanation. I was incredibly disappointed. Then, out of the blue, they changed their minds because they thought the other girl was too big - a sign of the times.'

Mason agreed to stay on in the supporting role of Rosamund, but Lambert found it hard to reconcile the fact that everyone felt she was the embodiment of Miranda when she was so introverted off screen. As a result, she often felt like an outsider. 'All the schoolgirls were lodged together,' she recalled, 'separately from the rest of the cast at a Christian women's guesthouse. It was like stepping back in time, with these sweet little rooms with lots of antimacassars. It was designed to help us bond, but it didn'#t happen for me - I was missing my family. With these cliques of young women, there were lots of feelings. Some of them decided that Jane Vallis, who played Marion, another of the disappeared characters, would pair up with Dominic Guard, who played the young Englishman who follows them. Any time I was with him, suddenly there would be this wall of girls in front of me; this instant kind of intervention.'

Indeed, it took an incident at the Rock to make Lambert feel comfortable in the role. 'I was the only character lucky enough not to have to wear a corset,' she explained, 'but clambering about on the rock in those little Victorian boots was brutal. I was still feeling insecure, because there had been something not very wholehearted about my casting. One lunchtime, after a horrible morning filming where I'd had to re-do a scene a number of times, I came down the Rock to see a little old woman staggering over some rough ground. I realised it was Joan Lindsay; she came up and threw her arms around me. Right in my ear, very emotionally, she said: "Oh, Miranda, it's been so long!" That was incredibly validating.'

The other principal role that had to be recast was Mrs Appleyard. Weir had originally chosen Vivien Marchant, but she fell ill just a fortnight before filming began and he was relieved that Rachel Roberts had been able to stand in at such short notice. 'The wig we'd made for Vivien also fitted her,' Weir recalled, 'but she said: "I simply can't wear it." It was bad luck in the English theatre to wear other actors' wigs. Luckily, she had one of her own that she was able to use. She was a consummate performer.'

Roberts came with her own baggage, however. In order to create a sense of distance from the younger cast members, she remained aloof from them for the entire shoot. But she also had a drinking problem and got so inebriated one night in Adelaide that she was found prancing naked around the hotel courtyard demanding to know if there was a man brave enough to spend the night with her. Her scenes were restricted to Martindale Hall, although Weir did take Roberts to the Rock to film her searching for the girls. There was also a shot of her body being carried away on a stretcher. But Weir had been so moved by the image of Mrs Appleyard staring into space at her desk that he dispensed with the alternative ending.

In order to give Boyd his midday windows at the Rock, assistant director Mark Egerton divided scenes into A, B, and C categories of importance and allocated shooting time accordingly. As they only had six weeks from 3 February 1975 to work in, his planning enabled things to run smoothly and even allowed Weir and Boyd to experiment with different camera speeds when filming the girls at the Rock in order to make their movements feel more ethereal. In post-production, Weir also added the rumble of an earthquake to the sound mix to increase the ominousness of the action. However, those working on the Rock always felt acutely aware of its power, as watches of the cast and crew kept stopping and John Jarratt remembers being caught in a heavy storm that had circled Hanging Rock without raining directly on it.

Weir asked composer Bruce Smeaton to incorporate a sense of antiquity and paganism into his score so that it could contrast with the colonial tweeness of the college. However, Weir also needed the music to distract viewers from trying to fathom what was happening on the screen, as he wanted them to remain baffled and unsettled by the terrifying ambiguity of the denouement. As a consequence, the director rejected Smeaton's original submission and he and the producers bombarded him with albums to inspire him to re-score the picnic scene. 'The whole way through,' he told critic Ivan Hutchinson at the time, 'both Peter and the McElroy brothers have been feeding me LP tracks. I think we got up to 17. But now, having started with Palestrina, Chopin, Mozart, Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel, Stravinsky, Pink Floyd, Hawkwind... they've ended up with Romanian panpipes. I find that there's nothing in common with those things.'

But, with a little help from some synthesizers and a Mellotron. Smeaton was able to capture the atmosphere of Hanging Rock, while Gheorghe Zamfir's pan flute caught the innocence of the students. Jim McElroy has claimed that he had remembered hearing Zamfir's pipes on a documentary and had pushed for their inclusion. But Smeaton insists that he had summoned up the pan flute from a Nana Mouskouri TV show and had suggested them to Weir after drawing a blank with some Ravel and Debussy.

Subsequent overuse have made the pipes sound a little corny half a century on. But they were highly innovative at the time. In siding with his twin, Hal McElroy has opined, 'As we know with everything, memories are faulty. Particularly with a hit. You'll find that everybody wants to rush and grab the credit.' Wherever the truth lies, the score is just one of the facets that make Picnic At Hanging Rock so distinctive and so indelible.

Half a Century of Speculation

After a clock had stopped in the cinema at 12 o'clock on the night of the premiere, Picnic At Hanging Rock opened at the Hindley Cinema Complex in Adelaide on 8 August 1975. When the girls who had played the students saw it, they were dismayed to discover that their voices had been dubbed by older professional actresses. Some of the reviews were similarly disquieted. One read; ' That's Weir, as in weird.'

Others kvetched about the lack of a resolution. But Weir insisted, 'I do love to walk away from a movie that keeps making itself in your mind.' He told Sight & Sound in 1976: 'My only worry was whether an audience would accept such an outrageous idea. Personally, I always found it the most satisfying and fascinating aspect of the film. I usually find endings disappointing: they're totally unnatural. You are creating life on the screen, and life doesn't have endings. It's always moving on to something else and there are always unexplained elements. What I attempted, somewhere towards the middle of the film, was gently to shift emphasis off the mystery element which had been building in the first half and to develop the oppressive atmosphere of something which has no solution: to bring out a tension and claustrophobia in the locations and the relationships. We worked very hard at creating an hallucinatory mesmeric rhythm, so that you lost awareness of facts, you stopped adding things up, and got into this enclosed atmosphere. I did everything in my power to hypnotise the audience away from the possibility of solutions...There are, after all, things within our own minds about which we know far less than about disappearances at Hanging Rock. And it's within a lot of those silences that I tell my side of the story.'

Numerous critics highlighted the references to sexuality during the outing, with Mrs Appleyard associating the Rock with 'venomous snakes' and even Miss McCraw pointing out that the it is 'quite young, geologically speaking', while noting its potential to gush forth lava from its depths. Other scholars have claimed the site as a symbol of 'colonised Otherness', in relation to the violence inflicted upon the Indigenous peoples to eradicate them from the land on which they had dwelt for centuries before the first Europeans had landed in 1788.

At one point, Weir superimposes a shot of the Rock over a close-up of Miranda's face and commentators have suggested that this is because each is the object of fantasies that have been projected upon them, in Miranda's case by Sara, Michael, and Mademoiselle de Poitiers. As Megan Abbott notes in her Criterion essay on the film: 'In this way, Picnic is a movie about the projection of desires...at the same time that it encourages our projections - the film itself becomes our Miranda. Just as she abandons everyone, withholding answers, Picnic similarly resists a solution. Because it refuses to settle on a truth, an answer, a resolution, we, like its characters, are left trapped in our own fantasies, ones that we would perhaps rather not acknowledge.'

Our guard should have been up from the opening caption, as 14 February 1900 fell on a Wednesday and not a Saturday. This is the first of many deceptions designed to keep the audience off the scent. Even the dating of Easter at the end is wrong, as it fell on 15 April and not 29 March 1900. But Weir has kept his secret, even though not all of his collaborators agreed with his decision to remove around seven minutes of footage to create the director's cut that is now on UK screens and is available to rent from Cinema Paradiso on high-quality DVD, Blu-ray, and 4K.

One of Joan Lindsay's biographers unearthed a first draft chapter that was omitted from the published text and which surfaced in 1987 as 'The Secret of Hanging Rock'. In this coda, as Edith runs back to the picnic party, she passes a woman in her underwear, who shouts 'Through!' to the other girls. When one of her classmates loosens Edith's corset to help her breathe, the others remove their own and throw them off the Rock, only for them to become suspended in mid-air while casting no shadow. Meanwhile, Miranda, Marion, and Miss McCraw follow a lizard into a crevice, only for the Rock to refuse to allow Irma to enter this 'hole in space' and, thus, she is prevented from entering the timewarp, that takes the missing girls into another dimension.

Colin Caldwell, a close friend of Lindsay who had visited Hanging Rock with her, believed that she could read the land like an ndigenous Australian. 'She was very much a mystic,' he told one interviewer. 'She could sense things in the landscape that others couldn't.' Some of the book was clearly inspired by Lindsay's time at the Clyde Girls' Grammar School in Melbourne, where she possibly heard the story of two girls who had apparently gone missing in the early 1800s. Yet Lindsay always contended that the text had come to her in a series of vivid dreams and the truth shall never now be known. But such unknowns merely add to the allure of both the book and the film and explain the number of fansites and forums related to them.

Made for just 443,000 AUD, the picture took five million AUD at the box office, with only Steven Spielberg's Jaws (1975) and John Guillermin's The Towering Inferno (1974) surpassing it. Picnic received seven nominations from the Australian Film Institute, but won none. Russell Boyd did earn a BAFTA for his cinematography - not that this impressed anyone in Hollywood. Weir tells the story of a potential distributor who had thrown his coffee cup at the screen after claiming to have wasted two hours on a dumb movie without an ending.

Indeed, Picnic At Hanging Rock wouldn't receive a US release until 1979, after the presence of Richard Chamberlain had made Weir's The Last Wave (1977) more palatable. Five decades later, the film that helped launch the Australian New Wave has inspired dozens of imitations. As Lena Dunham claimed, 'Every fashion film and NYU undergraduate thesis takes its cues from this lyrical masterpiece. In college I tried to make a satirical remake entitled Lunchtime At Dangling Boulder, but all my actors slept too late.' In 2018, Larysa Kondracki, Michael Rymer, and Amanda Brotchie succeeded in sharing the directing duties on a six-part TV remake of Picnic At Hanging Rock, with Natalie Dormer as Mrs Appleyard. This is also available on DVD from Cinema Paradiso.

None of the original cast was involved. Margaret Nelson, who had played Sara, never acted again and has refused all requests to discuss her part. Sadly, Jane Vallis, who pressed flowers as a hobby like Marion, died of cancer at the age of just 36 in 1993. In A Dream Within a Dream, Christine Schuler reveals that her husband had fallen for her while watching her play Edith. But, while she has remained in Australia, Karen Robson followed Irma in travelling abroad, as she became a high-powered Hollywood lawyer and married Iranian-born director Ramin Niami.

We'll leave the final word to Anne Louise Lambert, whose performance as Miranda has inspired thousands of hypotheses: 'There have been times in my life when I thought the film was a load of fluff, like a shampoo commercial. About 10 years ago, Indigenous groups started objecting to it - which I understand, when the history of the Rock is so much greater - and I decided not to talk about the film. But I recognise it's got this extraordinary life force that keeps it going. I'm a psychotherapist now, and it has this Jungian aspect in the unsolved mystery: the exploration of society's shadow side, all the murky stuff that is brought up when the girls disappear.'

-

L'Avventura (1960) aka: The Adventure

Play trailer2h 23minPlay trailer2h 23min

Play trailer2h 23minPlay trailer2h 23minDespite having realised that her relationship with boyfriend Sandro (Gabriele Ferzetti) is in trouble, Anna (Lea Massari) joins him and some friends on a yachting trip in the Mediterranean. When they stop in the Aeolian Islands, Anna goes missing and Claudia (Monica Vitti) helps Sandro search for her best friend.

- Director:

- Michelangelo Antonioni

- Cast:

- Gabriele Ferzetti, Monica Vitti, Lea Massari

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

The Virgin Spring (1960) aka: Jungfrukällan

1h 26min1h 26min

1h 26min1h 26minIn medieval Sweden, Per Töre (Max von Sydow) sends his young daughter, Karin (Birgitta Pettersson), on an errand to make an offering to the church that lies on the other side of the forest. She is accompanied by Ingeri (Gunnel Lindblom), a pregnant servant, who secretly believes in the pagan Norse god, Odin.

- Director:

- Ingmar Bergman

- Cast:

- Max von Sydow, Birgitta Valberg, Gunnel Lindblom

- Genre:

- Drama, Thrillers, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

The Beguiled (1971)

1h 40min1h 40min

1h 40min1h 40minWhen 12 year-old Amy (Pamela Ferdin) brings wounded Union soldier John McBurney (Clint Eastwood) to the Miss Martha Farnsworth Seminary for Young Ladies in rural Mississippi, he has a disquieting effect upon the principal, inexperienced teacher Edwina (Elizabeth Hartman), and precocious 17 year-old student, Carol (Jo Ann Harris).

- Director:

- Don Siegel

- Cast:

- Clint Eastwood, Geraldine Page, Elizabeth Hartman

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

The Shout (1978)

Play trailer1h 23minPlay trailer1h 23minComposer Anthony Fielding (John Hurt) and his wife, Rachel (Susannah York). come to regret extending their hospitality to a mysterious drifter, Crossley (Alan Bates), when he tells them of his encounter with an Aboriginal shaman who could emit a 'terror shout' that was capable of killing anyone who heard it.

- Director:

- Jerzy Skolimowski

- Cast:

- Alan Bates, Susannah York, John Hurt

- Genre:

- Drama, Horror

- Formats:

-

-

The Virgin Suicides (1999) aka: Sofia Coppola's the Virgin Suicides / The Lisbon Sisters

Play trailer1h 33minPlay trailer1h 33min

Play trailer1h 33minPlay trailer1h 33minLooking back to 1975, a group of young men try to discern the reasons why Therese (Leslie Hayman), Mary (A.J. Cook), Bonnie (Chelse Swan), Lux (Kirsten Dunst), and Cecilia (Hanna R. Hall) - the five daughters of strict Christian parents (James Woods and Kathleen Turner) - would have wanted to end their own lives.

- Director:

- Sofia Coppola

- Cast:

- Giovanni Ribisi, Kirsten Dunst, Josh Hartnett

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

Innocence (2004)

1h 52min1h 52min

1h 52min1h 52minEmerging from a coffin at an exclusive educational establishment at which Mademoiselles Edith (Hélène de Fougerolles) and Eva (Marion Cotillard) teach ballet and biology, five year-old Iris (Zoé Auclair) clings to senior girl, Bianca (Bérangère Haubruge), even though she disappears each night without explanation.

- Director:

- Lucile Hadzihalilovic

- Cast:

- Zoé Auclair, Lea Bridarolli, Bérangère Haubruge

- Genre:

- Drama

- Formats:

-

-

Not Quite Hollywood (2008)

Play trailer1h 39minPlay trailer1h 39min

Play trailer1h 39minPlay trailer1h 39minWant to know how Picnic At Hanging Rock fits into the wider history of Australian cinema in the 1970s and 80s? Then, there's no better source of information and viewing suggestions than Mark Hartley's lively account of a new wave golden age.

- Director:

- Mark Hartley

- Cast:

- Phillip Adams, Glory Annen, Christine Amor

- Genre:

- Documentary

- Formats:

-

-

Cracks (2009)

Play trailer1h 40minPlay trailer1h 40min

Play trailer1h 40minPlay trailer1h 40minIn 1930s England, Di Radfield (Juno Temple) worships Miss G (Eva Green), the diving teacher who is an old girl of the elite boarding school, St Mathilda's. However, her nose is put out of joint when Miss G's attention shifts to new Spanish student, Fiamma Coronna (Maria Valverde).

- Director:

- Jordan Scott

- Cast:

- Eva Green, Juno Temple, María Valverde

- Genre:

- Drama, Lesbian & Gay

- Formats:

-

-

The Falling (2014)

Play trailer1h 38minPlay trailer1h 38min

Play trailer1h 38minPlay trailer1h 38minForever being picked on by Miss Mantel (Greta Scacchi) in an exclusive school in late-1960s England, 16 year-old Abigail (Florence Pugh) becomes pregnant after sleeping with the brother of her best friend, Lydia (Maisie Williams). When Abigail dies tragically, Lydia and other girls start to experience fainting fits that send the whole school into turmoil.

- Director:

- Carol Morley

- Cast:

- Maxine Peake, Maisie Williams, Florence Pugh

- Genre:

- Drama, Sci-Fi & Fantasy

- Formats:

-

-

Picnic at Hanging Rock (2018)

5h 7min5h 7min

5h 7min5h 7minHeadmistress Hester Appleyard (Natalie Dormer) faces a crisis when teacher Greta McCraw (Anna McGahan) and three teenage students, Miranda Reid (Lily Sullivan), Irma Leopold (Samara Weaving), and Marion Quade (Madeleine Madden), go missing during a picnic on St Valentine's Day in 1900.

- Director:

- Larysa Kondracki

- Cast:

- Natalie Dormer, Lily Sullivan, Lola Bessis

- Genre:

- TV Dramas, TV Mysteries

- Formats:

-