With Jennifer Kent's The Babadook celebrating its 10th anniversary, Cinema Paradiso marks the occasion with a special Halloween What to Watch Next.

Jennifer Kent is a firm believer in the visceral power of horror. Yet, she also insists that the genre affords film-makers greater freedom to discuss taboo topics with an intellectual and emotional rigour and frankness that would not be possible with a conventional drama.

Thus, while she wanted The Babadook (2014) to examine the impact of unresolved grief and suppressed depression, Kent also wanted to confront viewers with physicalised fear so that they could experience the sensation of feeling so enmeshed in the depths of a dark shadow that the only way out was to address their outer and inner terrors.

As she told one interviewer, 'I wanted it to feel like a pair of hands gently placed on the audience's neck, growing tighter and tighter and tighter until they felt they couldn't breathe.' Not only did she succeed in her aim, but Kent also created the most disturbing picture in the first hundred years of Australian horror.

Things That Go Bump Down Under

For decades, horror wasn't in the Australian screen lexicon. The silent era had yielded the odd creepy thriller, such as Frank Barrett's The Strangler's Grip (1912) and Charles Villiers's The Face At the Window (1919), while a hint of the supernatural had informed John Cosgrove's The Guyra Ghost Mystery (1921) and Raymond Longford's Fisher's Ghost (1924). But the censor took such a dim view of the genre that virtually no horror movies were shown until the late 1960s.

Moreover, as there was no sustained tradition of horror writing, Australia failed to produce its own Edgar Allan Poe or Bram Stoker. All that changed in 1961, however, when novelist Kenneth Cook deposited a timid Sydney schoolteacher in a sinister outback town. It took 10 years before Canadian Ted Kotcheff brought Wake in Fright (1971) to the screen, but it set a benchmark and inspired Terry Bourke to become the country's first horror specialist with Night of Fear (1973), Inn of the Damned (1975), and Lady, Stay Dead (1981).

None of these early outings is available on disc, while Ralph Lawrence Marsden's The Sabbat of the Black Cat (1973) has slipped into undeserved obscurity. Peter Weir fared better when he built supernatural elements into Picnic At Hanging Rock (1975), The Last Wave (1977), and The Plumber (1979). But the genre finally took off thanks to the Cormanesque efforts of producer Antony I. Ginnane, whose Ozploitation exploits are commemorated in Mark Hartley's excellent documentary, Not Quite Hollywood (2008).

Cinema Paradiso users can sample some of the shivers generated by Richard Franklin's psychokinesis thriller, Patrick (1978); Rod Hardy's vampire chiller, Thirst (1979); David Hemmings's supernatural saga, The Survivor (1981); and Brian Trenchard-Smith's dystopic slaughter fest, Turkey Shoot, 1982). A number of features dwelt on the mysteries of the outback, the best of which was Colin Eggleston's Long Weekend (1978), which was scripted by Everett De Roche, who was also responsible for Richard Franklin's Roadgames (1981), which starred Stacey Keach and Jamie Lee Curtis, and Russell Mulcahy's Razorback (1984), which introduced the 'creature feature' into Aussie cinema.

Philippe Mora's Howling III: The Marsupials (1987) soon followed, while the slasher arrived in the form of John D. Lamond's Nightmares (1980). Jim Sharman, the director of The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), teamed with Nobel Prize-winning author, Patrick White, for a little suburban unease in The Night, the Prowler (1978), while Tony Williams dabbled in haunted house tropes in Next of Kin (1982). The ever-innovative Brian Trenchard-Smith combined sci-fi, chills, and satire in Dead End Drive-In (1986) before Colin Eggleston ushered in some Outback Vampires ahead of the legion of dead soldiers in Carmelo Musca and Barrie Pattison's Zombie Brigade (both 1987), which screened at the Cannes Film Festival.

Perhaps the most gripping film of this period was Phillip Noyce's ocean-set, Dead Calm (1989), which saw Billy Zane menace Sam Neill and Nicole Kidman aboard their yacht. But gore was to the fore in Philip Brophy's splatter prototype, Body Melt (1993), which inspired several copycat mediocrities. More amusing was Kimble Rendall's Cut (2000), which paired Kylie Minogue and Molly Ringwald in a Scream wannabe that really should be available on disc, if only for the kitsch factor. There was nothing coy about Greg McLean's Wolf Creek (2005), however, in which ocker Mick Taylor (John Jarratt) abducts and torments a trio of backpackers in the wilds of Western Australia.

Breaking box-office records for a horror, this knowing homage to the Hollywood slasher sparked a mini-boom that included the respective zombie and vampire romps, Undead (2003) and Daybreakers (2009), which were written and directed by Peter and Michael Spierig, who subsequently made the US co-productions, Predestination (2014) and Winchester (2018), which were respectively headlined by Ethan Hawke and Helen Mirren. But the most successful Australian horror was made in America, as Leigh Whannell and James Wan couldn't find backing at home for Saw (2004), which spawned nine sequels (all of which are available from Cinema Paradiso), with a tenth being in the pipeline. This lack of support within the Australian film industry would have been eminently familiar to Jennifer Kent in 2014, as the fortysomething sought financing for her debut feature.

A Nine-Year Itch

'I came into the world knowing exactly what I wanted to do,' Jennifer Kent once proclaimed. Perhaps that was because she was related to pioneering siblings Edward John and Daniel Joseph Carroll, who had promoted the first Australian feature, Charles Tait's The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906), and distributed Raymond Longford's The Sentimental Bloke (1919), which was the first Australian picture to be a success in New Zealand and Britain.

'By the age of about six,' Kent recalled, 'I was writing plays and directing and acting, which was just a natural, joyful thing for me, and I really loved doing it. I kept doing it all the way through my childhood.' As she didn't know that 'girls could make films', Kent enrolled at the National Institute of Dramatic Art in Sidney, whose alumni included Mel Gibson, Judy Davis, and Geoffrey Rush. Having spent several years on stage and televsion, while also making occasional features like George Miller's Babe: Pig in the City (1998), Kent realised that she was on the wrong side of the camera.

Determined to learn as quickly as possible, Kent wrote to Danish director Lars von Trier and got to serve as an assistant on Dogville (2003). Fresh from her 'film school', she put her experience to the test in making Monster (2005), a short in which a single mother (Susan Prior) being driven crazy by her energetic young son (Luke Ikimis-Healey) finds herself dealing with a sinister interloper in a cupboard.

Well received at festivals, this 10-minute chiller was inspired by the experience of a friend who had calmed her child's fears of a boogeyman in their house by talking to it whenever it 'appeared'. Monster came to be known as 'baby Babadook', as Kent decided, after completing the 'Love Crimes' episode of the TV series, Two Twisted (2006), to expand it to feature length. In fact, she had written six or seven other storylines, but received little encouragement in developing them. Rather than succumbing to disillusion, however, Kent thought, 'Stuff this! I haven't given up. Go outside of Australia and try and develop something in another country!'

Securing a place on the writing programme at Binger Filmlab in Amsterdam, Kent spent six months working with mentors and exchanging feedback with other screenwriters, as she rethought Monster through three drafts of a feature script. 'With The Babadook,' she explained, 'I was always quite fascinated by people who could suppress really dark, deep, painful experiences and I wanted to explore the idea that perhaps pushing down on those terrible experiences is harder than facing them.'

Having just lost her father, Kent was inspired by her own struggle to come to terms with the pain. 'I was in this very real and personal space,' she revealed, 'and I tend to write from a personal space...So the treatment spoke to this idea of a person who could not feel the necessary pain or grief because it was so frightening to her, and the way that she lost her husband was so frightening that she pushed down on it. I was fascinated with this idea of someone pushing down so much and the pain having such energy that it had to go somewhere. So it splits off and becomes a separate thing that says, "Look at me. Remember me?" That's where the terror is.'

Back in Sydney, Screen Australia offered to provide development money and Kent was able to cast NIDA classmate Essie Davis as the mother after she had been attached to one of her earlier unrealised projects. 'It's surprising that Jen didn't have an incredible career as an actress,' Davis confided, 'because she was phenomenal. But I'm glad that she became a writer and director, because now she's giving me the opportunity to work with her and play the parts that she has created.'

Kent started writing in 2009 and needed five drafts to perfect the storyline and its characters. 'What was really important to me was to explore the necessity of facing the dark side,' Kent divulged in an interview. 'We cannot keep the skeletons in the closet. By suppressing that darkness, we not only hurt ourselves, but all those around us. The mother-son relationship was a by-product of that core investigation. It's also a fascinating area to cover because it's such a taboo. So many women feel it, like, "Oh, my god! I want to strangle my kid! He's driving me mad!" No mother can ever say that though! Mothers are just meant to love their children, but it's not always the case. It's hard for women to be a mother.'

'I'm not saying we all want to go and kill our kids,' Kent clarified, 'but a lot of women struggle. And it is a very taboo subject, to say that motherhood is anything but a perfect experience for women.' She continued: 'I'm not a parent, but I'm surrounded by friends and family who are, and I see it from the outside…how parenting seems hard and never-ending. I thought the film was going to get a lot of flak for Amelia's obvious shortcomings as a mother, but oddly, I think it's given a lot of women a sense of reassurance to see a real human being up there. We don't get to see characters like her that often.'

A Bad Book

Single mother Amelia Vanek (Essie Davis) is struggling to cope with Samuel (Noah Wiseman), the boisterous six year-old who was born on the same day that his father, Oskar (Ben Winspear), was killed in a crash while driving Amelia to the hospital. She now works at a care home in Adelaide and is often exhausted when Sam starts performing magic tricks and wielding weapons to protect her from an imaginary monster. Her problems are exacerbated, however, when Sam comes to believe that the sinister top-hatted figure in a bedtime storybook entitled, Mister Babadook, is real.

Amelia has no idea where the pop-up volume has come from and refuses to read it after Sam becomes convinced that the Babadook exists. She is unnerved herself when she hears strange sounds and doors keep opening. When she ventures into the basement, she even sees Mister Babadook's outline in a coat hanging on a peg. Sam blames the interloper after Amelia finds shards of glass in her soup. But the boy also starts getting into trouble at school and being cheeky to elderly neighbour, Gracie (Barbara West).

Amelia tries to confide in her sister, Claire (Hayley McElhinney), but she has run out of patience with the still-grieving Amelia and Sam's increasingly erratic behaviour around his cousin, Ruby (Chloe Hurn), even though she teases him about not having a father and being scared of the Babadook. Following an incident involving Sam's homemade weapons, his mother is called into school and she accuses the principal of not caring about her son. However, Claire has suggested that Amelia doesn't love him, either, and she feels at the end of her tether when Sam has a seizure after breaking Ruby's nose by pushing her out of a treehouse at her birthday party.

A doctor prescribes tranquilisers to calm Sam down, only he claims that his mother has been doping him when social workers pay a visit. Even though Amelia has ripped up the book and thrown it in the bin, strange things keep happening around the house. She even finds the restored book on the doorstep and is horrified to find that new images have been added, including ones in which she kills Sam and his pet dog, Bugsy, before slitting her own throat.

Shortly after she burns the book, Amelia receives a phone call in which the Babadook mocks her. She tries to report the incident to the police, but has no evidence. That night, the Babadook comes into her bedroom and leers at her from the ceiling. Grabbing Sam, Amelia sits up all night watching television, but still hallucinates that she has pulled a knife on Sam, only to discover that she has been subconsciously listening to a news report about a mother stabbing her son on his birthday.

Feeling guilty for shouting at Sam when he asks for something to eat, Amelia takes him out for a treat. But a knocking on the car roof causes her to plough into another car and she leaves the scene of the accident. Back home, she sees a vision of Oskar promising to return to her if she gives him the boy. Realising that this is the work of the Babadook, she tries to resist. But it possesses her and she breaks Bugsy's neck before banging on Sam's bedroom door demanding to be let inside.

When she screams that she wishes he had died instead of his father, Sam challenges Amelia with his weapons and lures her to the basement, which he has booby-trapped. Although he has tied her down, she still manages to grab him by the throat. However, Amelia summons her inner strength to resist the Babadook and frees herself by vomiting black bile. Reminded that she can't get rid of the Babadook, Amelia follows when Sam is suddenly whisked upstairs. She bellows at the creature to leave her son alone and a dazzling light fills the room before the Babadook emits a dreadful scream and flees into the basement, bolting the door behind it.

On Sam's birthday, the social workers commend Amelia for getting things back to normal. When they leave, she and Sam dig up worms in the garden and Amelia leaves them in a dish outside the basement door for the now impotent Babadook to drag inside with a rumbling grumble. Out in the sunshine, mother and son embrace lovingly.

Making Monsters

Just as the pop-up book drives the narrative, it also proved key to the film's look and feel. Kent knew that she had to find the right name for the character who slinks off the page to terrorise Amelia and Sam. 'I wanted it to be like something a child could make up, like "Jabberwocky" or some other nonsensical name,' the director revealed. 'I wanted to create a new myth that was just solely of this film and didn't exist anywhere else.'

Sounding both whimsical and menacing, the name 'Babadook' derives from 'babaroga', which is the Serbian term for 'boogeyman'. However, it has also been noted that 'ba-badook' in Hebrew translates as 'He is coming for sure', while the word is also an anagram for 'a bad book'. It was also handy for rhymes like, 'If it's in a word, or it's in a look, you can't get rid of the Babadook.'

Before she started work on the visual side of the film, Kent commissioned illustrator Alex Juhasz to create, Mister Babadook, as she envisaged that the design of the film would take its cues from the pop-up book. 'The book felt handmade and raw,' Kent said in an interview. 'and that's how I wanted the energy of the film to feel. We created that world as much as possible first, and the production design then had to mirror that.'

Following the template established in Monster, Mister Babadook wore a black cloak and top hat and had long clawed fingers. Kent showed Juhasz the cut-out figures that Lotte Reiniger had animated for The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926), although she also had in mind The Man in the Beaver Hat, who had been played in Tod Browning's lost silent, London After Midnight (1927), by Lon Chaney, who was known as 'The Man of a Thousand Faces'.

Another master from an earlier phase of the silent era also had a role to play, as not only did Kent borrow from the look of Georges Méliès's pioneering shorts, but she included clips from The Four Troublesome Heads (1898), Le Livre magique (1900), Dislocation mystérieuse (1901), The Infernal Cakewalk, The Damnation of Faust (both 1903), The Haunted House (1906), and L'Éclipse du soleil en pleine lune (1907). These form part of Amelia's television viewing during her long, dark night on the sofa, which also included Rupert Julian's The Phantom of the Opera (1925), Lewis Milestone's The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946), and Mario Bava's Black Sunday (1960). Also popping up is an episode of Skippy the Bush Kangaroo (1968-70), the popular children's TV programme that spawned the feature, Skippy and the Intruders (1969).

Also significiantly influential were F.W. Murnau's Nosferatu, Benjamin Christensen's Häxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages (both 1922), Jean Epstein's The Fall of the House of Usher (1928), and Carl Theodor Dreyer's Vampyr (1932). Indeed, Kent initially hoped to shoot in black and white to underline the Expressionist mood. Production designer Alex Holmes was also made aware of Georges Franju's Eyes Without a Face (1960) and Herk Harvey's Carnival of Souls (1962), while Kent sought inspiration for the dislocated atmosphere from the Roman Polanski trio of Repulsion (1965), Rosemary's Baby (1968), and The Tenant (1976), while also taking notes from Nicolas Roeg's Don't Look Now (1973), Tobe Hooper's The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), John Carpenter's Halloween (1978) and The Thing (1982), Stanley Kurick's The Shining (1980), David Lynch's Mulholland Drive (2001), and Tomas Alfredson's Let the Right One In (2008). All bar one of these titles are available with a single click from Cinema Paradiso.

In keeping with the sense of heightened realism drawn from these classic pictures, Kent decided to eschew computer-generated imagery. 'There can be something really visceral about things created in-camera,' she averred. 'You get the feeling there was something there.' By a happy accident, Kent realised how effective art department member Tim Purcell was when he played the Babadook during camera tests. But she also entrusted the creation of a mock-up monster to the Australian company, Anifex, with puppetry and stop-motion animation being used to ensure his movements appeared more eerily authentic. A little computerised smoothing was done in post-production, but Kent stuck to her guns that 'the brain responds differently when you're seeing something play out in camera'. As she told Empire magazine, 'There's been some criticism of the lo-fi approach of the effects, and that makes me laugh because it was always intentional. I wanted the film to be all in camera.'

The physical presence of the foe also made it easier for the actors to react than it would have done had they been in front of a green screen. Moreover, by casting shadows over the sets, Kent and Polish cinematographer Radek Ladczuk were able to fill the CinemaScope frame with such dread that the threat of seeing the Babadook actually became more daunting than coming face to face with it. But the ominous atmosphere posed problems of its own when it came to filming Sam's scenes.

Casting director Nikki Barrett viewed around 500 audition tapes before selecting a number of boys to work in group and solo improvisations. Although Kent had imagined Sam to be eight or nine, she was so impressed by six year-old Noah Wiseman that she rethought the character. The son of a child psychologist, he had an innocence that set him apart and Kent spent a lot of time forging a bond between Davis and Wiseman through playing games before they started a limited rehearsal period, as Kent didn't want to overwhelm the boy with too much line-learning.

Wiseman's mother was always on the set so he felt safe and Kent came up with a kiddie version of the plot so that he knew he was playing a hero protecting his mother without having to hear about the scarier aspects. Kent took him to Adelaide zoo to tell Wiseman how crucial he was to the success of the film, while emphasising that he was under no pressure once the camera started rolling.

When the action became unsuitable for young ears, Wiseman was spirited away and Davis delivered her lines to a crouching stand-in. By contrast, Davis perched herself on the camera trolley during Wiseman's close-ups so that he could deliver his lines to her. The odd bit of subterfuge was used to provoke necessary reactions. 'He really loved his Lego,' Kent remembered, 'so Essie was saying things like "I'm gonna take all your Lego and I'm gonna shove it in a bag and pour cement in it and throw it into the river", and he was furious about that.' This way of working was time-consuming. But Kent was adamant, 'I didn't want to destroy a childhood to make this film - that wouldn't be fair.'

While a Victorian terraced house was found in North Adelaide for the exteriors, Kent was keen to avoid the film feeling too Australiany. Consequently, she shot primarily on studio soundstages that were predominantly painted black and white with splashes of blue and burgundy. The walls of the sets were moveable so that the rooms could appear larger or smaller, as Amelia's perspective was altered by the Babadook's burgeoning presence. Kent would also push Davis towards the edge of the frame to tease the audience about the intruder's whereabouts.

In order to enhance his scare quotient, Kent's sound team borrowed a dragon's roar from the video game Warcraft II: Beyond the Dark Portal, while audio effects were also sampled from UFO: Enemy Unknown, Mortal Kombat 3, and Resident Evil. But the basement in which the finale was filmed provided its own unique ambience. 'The house was a set,' Kent divulged, 'but the basement was real, and it's haunted. I've got photos of ghosts in there. I was demonstrating that backward thing that [Essie] does, and she was holding the camera. We felt this bit of light go by, and we both said, "Whoa," at the same time. Then we looked at the photo, and there was a photo of me bending backward with this big wave of light flying past.'

Elevating Horror

Jennifer Kent has an abiding memory of The Babadook's premiere at the Sundance Film Festival. 'When the film ended,' she recalled, 'the woman in front of me said, "Well, that was crap."' The picture had cost A$2.5 million, with the last A$30,071 having been provided by 259 crowdfunders responding to a Kickstarter appeal in June 2012 to supplement the grants from Screen Australia and the South Australian Film Corporation. Yet it took only A$258,000 after being released into just 13 cinemas in its homeland.

Speaking to The Cut, Kent claimed that Australians 'have this inbuilt aversion to seeing films [from Australia]. They hardly ever get excited about their own stuff. We only tend to love things once everyone else confirms they're good...We don't think a lot of our own output. Creatives [from Australia] have always had to go overseas to get recognition. I hope one day we can make a film or work of art and [people from Australia] can think it's good regardless of what the rest of the world thinks.'

Critics overseas were more positive, however, with American Glenn Kenny declaring The Babadook to be 'the finest and most genuinely provocative horror movie to emerge in this still very-new century'. Variety's Scott Foundas noted that the film 'manages to deliver real, seat-grabbing jolts while also touching on more serious themes of loss, grief and other demons that can not be so easily vanquished'. But the most notable response came from William Friedkin, the director of The Exorcist (1973), who tweeted, Psycho, Alien, Diabolique, and now THE BABADOOK.' He later added, 'I've never seen a more terrifying film. It will scare the hell out of you as it did me.'

Off the back of such notices, The Babadook went on to gross $10.3 million at the global box office. It was also popular on disc, but it received a new lease of life after it was accidentally categorised as a LGBTQIA+ title on Netflix. The notion caught fire online, where it was suggested that Mister Babadook's partner was Pennywise the clown from It (2017) and It: Chapter Two (2019). People turned up to pride parades in Babadook costumes, as did a contestant on RuPaul's Drag Race.

Despite being delighted to have created a gay icon, Kent has resisted all talk of a sequel. 'I will never allow any sequel to be made, because it's not that kind of film,' she stated. 'I don't care how much I'm offered, it's just not going to happen.' She also dislikes the label 'elevated horror' that has been used by many to distinguish a film 'with stuff on its mind' from torture porn titles like Eli Roth's Hostel (2005) and such found footage offerings as Oren Pell's Paranormal Activity (2007). Yet the term has a certain validity, as Kent's feature has 'personal demon' things in common with items like Julia Ducournau's Raw (2016), Ari Aster's Hereditary (2018) and Midsommar (2019), Rose Glass's Saint Maud (2019), and Natalie Erika James's Relic (2020).

Indeed, Jordan Peele, the director of the Oscar-nominated Get Out (2017) told Lupita Nyong'o to watch The Babadook while preparing to play a woman who is menaced by her doppelgänger in Us (2019). Fellow Aussie James Wan also paid homage to Kent as the producer of Gerard Johnstone's M3gan (2022) by opening the picture with a car crash and having the young girl at its heart become unnerved by a novelty plaything.

As for Kent, Hollywood came calling in the form of Warner Bros, who considered her for Wonder Woman (2017) before settling on Patty Jenkins. She was also in the discussion at Marvel Studios for Captain Marvel (2019), but the gig went to Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck. Not being particularly enamoured of Tinseltown, Kent returned home to direct The Nightingale (2019), a tale of revenge set in 19th-century Tasmania that also examines attempts to wipe out the local population. 'It was a really crazy time for women,' Kent told The Guardian. 'We only hear the sanitised version and I wanted to explore it for real. I couldn't go down to Tasmania - which was the worst place, the worst attempted annihilation of a culture - and not do this the right way. I feel that we're grown up enough now to look at it and accept it as part of our history.'

While developing other feature ideas, Kent reunited with Essie Davis in 2022 to contribute 'The Murmuring' to Guillermo Del Toro's anthology series, Cabinet of Curiosities. However, she would prefer to do things off her own bat at her own pace. 'I'm still not really majorly impressed by Hollywood and the system here,' she confided in one journalist, 'but it's an adventure...I don't take it too seriously though. I just continue with my own work, and that's what I feel very strongly about. There have been wonderful opportunities, but I really just want to tell my own stories.'

One of them concerns her comatose father's last days and would centre on various characters in three different worlds. Kent also has an announcement pending about adapting a book by a well-known horror writer. In the meantime, she will continue working on a project set in Ireland in the 1700s. 'It deals with Irish folklore,' she disclosed. 'I'm working with a fellow writer on that. It's a six-part one-off series. Irish myth and folklore. You think it's these dancing leprechauns, but in actuality, a lot of the mythology is very frightening.' Sounds good to us!

-

The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946) aka: Love Lies Bleeding / Meaningful Glances / Strange Love

1h 56min1h 56min

1h 56min1h 56minAmong the films Amelia watches during a long night dreading Mister Babadook, Lewis Milestone's noir follows prodigal son Sam Masterson (Van Heflin), when he returns to Iverstown and falls for fellow hotel guest, Toni Marachek (Lisabeth Scott). However, old friend Walter O'Neil (a debuting Kirk Douglas) thinks he's back to blackmail his rich wife, Martha Ivers (Barbara Stanwyck), over the death of her aunt years before.

- Director:

- Lewis Milestone

- Cast:

- Barbara Stanwyck, Van Heflin, Lizabeth Scott

- Genre:

- Drama, Thrillers, Classics, Romance

- Formats:

-

-

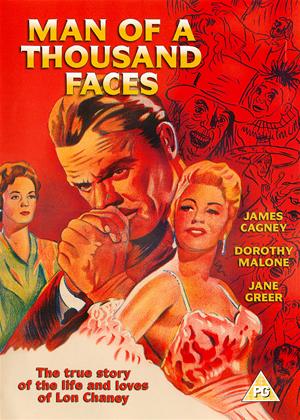

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Play trailer2h 1minPlay trailer2h 1min

Play trailer2h 1minPlay trailer2h 1minJennifer Kent drew inspiration from Tod Browning's London After Midnight (1927), which starred Lon Chaney. He's the subject of this Joseph Peveney biopic, which stars James Cagney as the son of deaf parents who finds fame in vaudeville before a scandal involving his singer wife, Cleva (Dorothy Malone), drives him to Hollywood, where he discovers a genius for creating macabre characters.

- Director:

- Joseph Pevney

- Cast:

- James Cagney, Dorothy Malone, Jane Greer

- Genre:

- Drama, Classics

- Formats:

-

-

Black Sunday (1960) aka: The Mask of Satan / La maschera del demonio

Play trailer1h 27minPlay trailer1h 27min

Play trailer1h 27minPlay trailer1h 27minAnother of the late-night movies that Amelia watches on the sofa, Mario Bava's directorial debut draws upon Universal and Hammer horror tropes in reworking Nikolai Gogol's short story, 'Viy', as an account of what transpires two hundred years after mid-17th-century Moldavian princess, Asa Vajda (Barbara Steele), curses her brother and vows vengeance on his descendants while being executed for witchcraft and vampirism.

- Director:

- Mario Bava

- Cast:

- Barbara Steele, John Richardson, Andrea Checchi

- Genre:

- Classics, Horror

- Formats:

-

-

Carnival of Souls (1962)

Play trailer1h 18minPlay trailer1h 18min

Play trailer1h 18minPlay trailer1h 18minDesigned to evoke the look of Ingmar Bergman and the feel of Jean Cocteau, Herk Harvey's sole directorial outing was also on Amelia's viewing list. In it, another car crash survivor, Mary Henry (Candace Hilligoss), takes up the post as a church organist in Utah. However, she is drawn to an abandoned fairground, where she is stalked by a mysterious stranger (Harvey).

- Director:

- Herk Harvey

- Cast:

- Candace Hilligoss, Frances Feist, Sidney Berger

- Genre:

- Thrillers, Classics, Horror

- Formats:

-

-

Paperhouse (1988)

Play trailer1h 29minPlay trailer1h 29min

Play trailer1h 29minPlay trailer1h 29minHaving previously been turned into the six-part ITV series, Escape into Night (1972), Catherine Storr's 1958 novel, Marianne Dreams, was brought to the big screen by Bernard Rose, who would go on to make Candyman (1992). The tale turns on a young girl named Anna (Charlotte Burke), who discovers that each time she adds details to a drawing she has made of a house, they crop up in her dreams - just like images that keep appearing in the blank pages of the pop-up book in The Babadook.

- Director:

- Bernard Rose

- Cast:

- Charlotte Burke, Jane Bertish, Samantha Cahill

- Genre:

- Sci-Fi & Fantasy, Horror

- Formats:

-

-

Melies the Magician (1997)

2h 10min2h 10min

2h 10min2h 10minTwo of the films that Amelia sees while seeking sofa sanctuary from the boogeyman in her bedroom, The Four Troublesome Heads (1898) and The Infernal Cakewalk (1903), appear in this collection of 15 restored shorts. Also included is Jacques Mény's documentary, The Magic of Méliès, which celebrates the cinematic wizardry of the stage magician who devised all manner of trick shots and special effects to delight audiences around the turn of the 20th century and inspire subsequent generations of film-makers.

- Director:

- Jacques Meny

- Cast:

- Georges Méliès

- Genre:

- Sci-Fi & Fantasy, Classics, TV Documentaries

- Formats:

-

-

Haunting Hour: Don't Think About It (2007) aka: R.L. Stine's the Haunting Hour: Don't Think About It

Play trailer1h 23minPlay trailer1h 23min

Play trailer1h 23minPlay trailer1h 23minA goosebump-giving R.L. Stine opus informs this Alex Zamm chiller, which sees teen goth Cassie (Emily Osment) come to regret purchasing a book entitled The Evil Thing from a Halloween store in her new hometown, as she ignores warnings not to read it aloud and has to rescue her brother from the monster she has summoned.

- Director:

- Alex Zamm

- Cast:

- Emily Osment, Brittany Curran, Cody Linley

- Genre:

- Children & Family

- Formats:

-

-

Prevenge (2016)

Play trailer1h 27minPlay trailer1h 27min

Play trailer1h 27minPlay trailer1h 27minThe death of a partner has a key role to play in Alice Lowe's directorial debut. Having lost her husband in a climbing accident, the heavily pregnant Ruth (Lowe) starts hearing her unborn daughter instructing her to go on a bloody killing spree. One might even call the ghoulish foetus a 'babydook'.

- Director:

- Alice Lowe

- Cast:

- Jo Hartley, Kate Dickie, Gemma Whelan

- Genre:

- Comedy, Drama

- Formats:

-

-

Hereditary (2018)

Play trailer2h 2minPlay trailer2h 2min

Play trailer2h 2minPlay trailer2h 2minIn Ari Aster's first feature, a tragic car accident turns mother Annie Graham (Toni Collette) against Peter (Alex Wolff), the son she holds responsible for her daughter's death. However, she realises that Peter is in danger from his sister's restless spirit when graphic drawings start appearing in the sketch pad she left behind.

- Director:

- Ari Aster

- Cast:

- Gabriel Byrne, Alex Wolff, Toni Collette

- Genre:

- Thrillers, Horror

- Formats:

-

-

Relic (2020)

Play trailer1h 29minPlay trailer1h 29min

Play trailer1h 29minPlay trailer1h 29minTorn pages from a photo album and something sinister lurking under a bed bind Aussie debutant Natalie Erika James's psychological thriller to The Babadook. There's also the creepy house that mother Kay (Emily Mortimer) and daughter Sam (Bella Heathcote) find empty because dementia-afflicted grandma Edna (Robyn Nevin) has gone missing. Or has she?

- Director:

- Natalie Erika James

- Cast:

- Robyn Nevin, Emily Mortimer, Bella Heathcote

- Genre:

- Thrillers, Drama, Horror

- Formats:

-