A year has passed since Bong Joon-ho's Parasite made history by becoming the first foreign-language film to win the Academy Award for Best Picture. Indeed, it also took the Oscars for Best Director, Original Screenplay and International Film, on top of having become the first South Korean feature to be awarded the Palme d'or at Cannes. Bong might have grabbed the headlines, but he belongs to a golden generation of Koren film-makers and it's high time that Cinema Paradiso took a look behind the ballyhoo surrounding the hallyu wave.

New waves never happen in isolation. They come about because various factors align and this is definitely the case with South Korean cinema around the turn of the millennium. In order to understand the contributing social, political and cultural forces, it's necessary to go back over a century to see how events on the Korean peninsula shaped a filmic consciousness that rarely indulges in populist escapism. Instead, there's an emphasis on the darker side of the human experience that couples with a subversive sense of innovation to give everything from romances and comedies to chillers and thrillers an edge that is both aesthetically distinctive and deeply rooted in the country's history and psyche.

The 'hallyu' (which means 'flowing from Korea') new wave was the result of a conscious decision enshrined within the 1999 Framework Act on the Promotion of Cultural Industries to stamp everything from fashion and cuisine to pop and cinema with a K brand. This wasn't just a kitschy marketing ploy, however, as foundations were laid to ensure that Korean cultural life boosted the nation's self-esteem and its image overseas. Such groundwork gave film-makers from the 386 Generation born in the 1960s the creative freedom to explore contentious topics and challenge audiences in a way that Hollywood blockbusters rarely did. Hence, the focus on revenge, the seedy side of society, the past's impact on the present, unlikely liaisons and humanity's potential for both decency and depravity. The formula was sufficiently flexible to be applied to mainstream and arthouse pictures alike and, as a result, South Korean cinema was transformed from a backwater to a powerhouse in just two decades.

Han Solo - A Korean Crash Course

South Korea is one of the world's most dynamic, prosperous and forward-thinking nations. Yet, underlying this positivity is the concept of 'han', a resilience born of suffering that derives from a traumatic century of invasion, division and repression. This notion of han courses through South Korean culture and the hallyu new wave can only be fully appreciated in its historical context, as it was only in the late 1990s that cinema was granted freedom of expression after decades of being a state-controlled ideological tool that was used to indoctrinate and control the public.

Between 1910-45, the Korean peninsula was under Japanese occupation, with strict censorship hampering the development of an indigenous film culture. In fact, local production had started late with Kim Do-san's Righteous Revenge (1919) and many of the features produced during the silent and early sound eras contained allegorical allusions to the country's plight. Restrictions were reinforced following the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937 and, five years later, Korean cinema was outlawed altogether.

Few of the films from the colonial period survive. But independence brought its own problems, especially when left-leaning artists sided with Kim Il-sung during the Korean War and only 14 features were produced in Seoul between 1950-53. Technically, North and South Korea remain in a state of ceasefire and the tense relationship across the 38th Parallel became a recurring theme during the brief golden age that saw Yu Hyun-mok's Obaltan borrow from neo-realism and Kang Dae-jin's The Coachman (both 1961) became the first South Korean film to win an award at an international film festival. The most important picture, however, was Kim Ki-young's The Housemaid (1960), a seething upstairs downstairs study that was to prove a significant influence on Bong Joon-ho's Oscar-winning Parasite (2019), which is available to rent from Cinema Paradiso on DVD, Blu-ray and 4K for the best possible viewing experience.

This renaissance didn't last long, however, as new leader General Park Chung-hee imposed the 1962 Motion Picture Law that so restricted autonomy that Lee Man-hee was arrested for making the North Korean characters too sympathetic in Seven Female POWs (1965). Only 'ideologically sound' pictures were permitted, although Lee Jang-ho and Im Kwon-taek tried to prevent cinema from becoming an irrelevance as South Koreans stayed home to watch television.

Amazingly, the government sanctioned saucy 'hostess films' like Kim Ho-sun's Yeong-ja's Heydays (1975) and Winter Woman (1977), which were the Korean equivalent to Japanese 'pinku-eiga' films became huge box-office hits. But the regime cared much less for cinema than Kim Jong-il, whose audacious 1976 bid to abduct director Shin Sang-ok and actress Choi Eun-hee is retold in Ross Abbott and Robert Cannan's The Lovers and the Despot (2016).

Glimmers of hope came with the foundation of the Korean Motion Picture Promotion Corporation in 1973 and the 1984 Motion Picture Law that permitted independent production for the first time in 30 years. Two years later, the boycott on foreign films was relaxed, although Park Woo-sang was already clearly au fait with Hong Kong action fare, as Duel of Ultimate Weapons (1983) ticks all the Martial Arts boxes. But it wasn't until 1987 that popular protests prompted the drafting of a new democratic constitution and the emergence of films like Park Kwang-su's Chilsu and Mansu and Jang Sun-woo's The Age of Success (both 1988) that the focus could finally turn to the socio-political themes that would give South Korean cinema a new intellectual integrity, as well as the commercial appeal to rival the Hollywood movies that dominated the domestic box office.

The First Inklings

A century after the first moving images had been projected on to a screen, South Korean cinema finally came of age. After decades of strict quotas, audiences had devoured the films imported from around the world and had so relished arthouse cinema that the Busan International Film Festival was launched in 1996 and quickly became a key event on the Asian calendar. Freed from stricture, directors like Kim Ui-seok (Marriage Story, 1992), Park Kwang-su (To the Starry Island) and the prolific Im Kwon-taek (Sopyonje, both 1993) attracted global attention. But it was Kang Je-kyu who took things in a new direction with The Gingko Bed (1996), in which artist Han Suk-yu buys a bed made from a cursed tree and pays for his recurring dreams of princess Kim Sun-kyung when murderous general Jin Hee-kying comes searching for him. Strewn with references to Korea's troubled past, the atmosphere of supernatural surrealism allowed audiences to reinterpret national history and reclaim it with a spirit of optimism.

Released in the same year as Lee Hyun-se's Hanime cartoon Armageddon (1996), Kim Ki-duk's debut feature, Crocodile, tapped into the same mood, as a feral man (Cho Jae-hyun) who lives under a bridge and preys upon suicide victims is forced to rethink when he rescues waif Woo Yoon-kyeong from the Han River. Lee Chang-dong's Green Fish also explored the violence in Korean society, as Han Suk-yu returns to his much-changed home town after military service to be lured into a deadly triangle involving crime boss Mun Seong-kun and his mistress, Shim Hye-jin. Han Suk-yu also impressed in Song Neung-han's jopok crime parody, No. 3 (both 1997), as a low-ranking henchman in the Do Ka Gang whose bid to take control is hampered by moll Lee Mi-yeon, rival kkangpae mobster Park Sang-myeon and prosecutor Choi Min-sik.

These ripples proved a false dawn, however, as the 1997 crash stalled Asia's Tiger economies and the film industry based on Seoul was forced to take stock. Yet, rather than fold, South Korean cinema bounced back with renewed vigour and a greater sense that a new generation of film-makers had emerged with a shared vision of how to channel the past in order to comment on the present. Kim Jee-woon literally showed where the bodies were buried in The Quiet Family (1998). a pitch black comedy in which a family's bid to start again by opening a mountain lodge is blighted by the high death rate among the guests. Inconvenient corpses also keep cropping up in Park Ki-hyeog's Whispering Corridors (1998), as old girl Li Mi-yeon returns to her school as a teacher amidst rumours that there's a ghost on the loose.

This creepy twist on Dario Argento's Suspiria (1977) spawned four sequels and Kim Tae-yong's Memento Mori (1999), Yun Jae-yeon's Wishing Stairs (2003), Equan Choi's Voice (2005) and Lee Jong-yong's A Blood Pledge (2009) are all available from Cinema Paradiso if you fancy having a haunted binge. The much-missed Tartan Video label had an excellent eye for Asian releases, but groundbreaking titles lke E J-yong's An Affair, Hur Jin-ho's Christmas in August (both 1998), Jung Ji-woo's Happy End, Jang Sung-woo's Lies and Kin Sang-jin's brilliant Attack the Gas Station! (all 1999) slipped through the net. Nevertheless, Cinema Paradiso can offer Kim Dong-bin's spin on the Suzuki Koki bestseller, The Ring Virus, K.C. Park's religious cult chiller, The Soul Guardians, and Chang Youn-hyun's Tell Me Something (all 1999), which features rising star Han Suk-yu as a cop on the track of a devious serial killer.

Moreover, among the tens of thousands of films on its books, Cinema Paradiso can also recommend three more 1999 pictures that set the Korean new wave into overdrive. Novelist-turned-director Lee Chang-Dong's Peppermint Candy is a treatise on Korean masculinity that trawls back over three decades to see why Sol Kyung-gu is standing on a railway line awaiting an oncoming train. Lee Myung-se's storytelling is equally meticulous in Nowhere to Hide, as Inchon detective Park Joong-Hoon hopes to use the devoted Choi Ji-Woo to lure master of disguise Ahn Sung-Ki out of the shadows in the midst of a murderous drug war.

The pick of the 1999 bunch, however, is Kang Je-kyu's Shiri, a landmark hallyu blockbuster that bears the hallmark of both the Hollywood action movie and the 'heroic bloodshed' outings of such Hong Kong maestros as John Woo, Ringo Lam and Tsui Hark. Focusing on North-South relations, this high-stakes thriller stars Han Suk-yu as a secret agent teamed with Song Kang-ho, who has no idea that fiancée Kim Yun-jin is an assassin controlled by Communist commander Choi Min-sik.

A Fallen Idol

As far as British audiences were concerned, the leading light of the Korean Wave was Kim Ki-duk. Born into a middle-class family in 1960, Kim dropped out of school and joined the Marines. However, he failed to settle into military life and developed an interest in painting while doing his volunteer service in a Baptist church. He spent the next two years in Europe, acquiring a reputation as a pavement artist before deciding that his future lay in critiquing his homeland through cinema.

In his fourth feature, The Isle, Kim appalled and impressed with equal measure, as he used cruelty to animals to examine the battle between the sexes that is epitomised by the exploitative relationship that evolves after fugitive Kim Yi-seok seeks sanctuary in one of the floating cottages at the fishing resort where mute Suh Jung provides a range of services to her customers. By contrast, artist Ju Jin-mo snaps and leaves seclusion to go in search of everyone who has ever wronged him in Real Fiction (both 2000). What he doesn't know, however, is that someone is documenting his crimes with a camcorder.

South Korea's relationship with the United States comes under scrutiny in Address Unknown, as those living near a military base build complicated relationships with those seeking to protect them. The film's title comes from the letters a woman keeps sending Stateside in the hope of finding her son's soldier father. But the obsession is markedly more sinister in Bad Boy (both 2001), a provocative study of crime, prostitution and male-female power games that sees college student Seo Won regret the rash act that left her dependent upon besotted gangster Cho Jae-hyun. Machismo also has calamitous consequences in The Coast Guard (2003), which chronicles the meltdown of Jang Dong-gun, a private whose eagerness to catch a North Korean spy in the Demilitarised Zone results in the death of a civilian and the nervous breakdown of girlfriend Park Ji-a.

Having been dismissed by some critics as a provocateur along the lines of Japan's Takaski Miike, Kim surprised everyone with Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter…and Spring (2003), a compelling contemplative drama that charts over 20 years the relationship between a Buddhist monk (Oh Yeong-su) and the young novice (Seo Jae-kyeong and Kim Yeong-min) whose life of peace and prayer in a pagoda on Jusan Pond is disrupted by the young woman (Ha Yeo-jin) who has awoken his baser desires. Stunningly photographed by Baek Dong-hyun, this proved to be the high point of Kim's career, although he respectively won the Silver Bear at Berlin and the Silver Lion at Venice for Samaritan Girl and 3-Iron (both 2004). The former tracks cop Lee Eol after he discovers that daughter Kwak Ji-min is sleeping with clients in remorse for the death of her prostitute partner, while the latter follows the fortunes of home-invading drifter Jae Hee and Lee Seung-yeon, the former model he rescues from her abusive husband.

Three also proves a crowd in The Bow (2005), as 16 year-old Han Yeo-reum is all set to marry Jeon Seong-hwang, the 60 year-old who has been devoted to her in the decade since he kidnapped her, when she falls for Seo Ji-seok, the student whose father has hired the fishing boat on which they live. The change of heart is triggered by jealousy in Time (2006), as Sung Hyun-oh becomes so fearful that boyfriend Ha Jung-woo will leave her that she dumps him and attempts to seduce him all over again after having had radical plastic surgery. A hint of the dark humour that marbles this chamber drama can also be detected in Breath (2007), another tale of envy and vengeance that sees housewife Park Ji-a discovers her husband's infidelity and embarks upon a relationship with Death Row prisoner Chang Chen.

During the making of Dream (2008), actress Lee Na-young almost died during a hanging scene and Kim retreated into writing and producing his next two features before returning front and centre in the offbeat documentary, Arirang, in which he explored from his exile in a remote cabin the psychological impact of Lee Na-young's brush with death and his own way forward as both a man and as an artist. Many wrote Kim off as a result of this exercise in self-laceration and the cool reception accorded Amen (both 2011). But he bounced back when he became the first Korean to take top prize at one of Europe's Big Three festivals when he won the Golden Lion at Venice for Pieta (2012), which sees brutal debt collector Lee Jung-jin get knocked for a loop when the woman who claims to have given him up at birth, disappears shortly after making contact.

Kim returned to the same festival the following year with Moebius (2013), a bleakly comic tale of domestic dysfunction that involves castration, incest and rape. The Korean authorities initially banned the film, but the largely supportive reviews were soon forgotten when the actress who had been replaced in a dual role by Lee Eun-woo anonymously accused the director of sexual impropriety and physical violence. Despite fighting to clear his name in court, Kim's reputation was irreparably tarnished when further allegations were levelled against him. Yet he managed to complete One on One (2014), Stop (2015), The Net (2016), Human, Space, Time and Human (2018) and Dissolve (2019) before he succumbed to coronavirus while seeking residency in Latvia in December 2020.

The Big Bong Theory

No sooner had Shiri broken box-office records by addressing the North-South divide without resorting to propagandist cliché, Park Chan-wook achieved similar success with Joint Security Area (2000). Park had worked as a critic after failing to follow-up his 1992 debut,The Moon Is...the Sun's Dream. But, echoing Akira Kurosawa's masterpiece, Rashomon (1950), JSA caught the public mood and became the most-seen film in Korean history because of the suspense Park generated as Swiss army major Lee Young-ae investigates the conflicting account given by North Korean survivor Song Kang-ho of the shooting of two comrades in the DMZ by South Korean border guard, Lee Byung-hun.

Buoyed by his success and the increased creative freedom it brought, Park released Sympathy For Mr Vengeance (2002), which set the new wave tone for the unflinching depiction of violence in chronicling the consequences of deaf-mute factory worker Shin Ha-hyun allying with anarchist girlfriend Bae Doo-na to kidnap the daughter of the man who had fired him (Song Kang-ho) in order to pay for his sister's kidney transplant. However, Park upped the ante in Oldboy (2003), the second part of his 'Vengence trilogy' that draws on a Japanese manga in showing how Choi Min-sik emerges from 15 years of captivity to join forces with sushi chef Kang Hye-jung in order to punish Yoo Ji-tae, the wealthy stranger who had not only incarcerated Choi, but also murdered his wife.

Having co-scripted Lee Moo-young's A Bizarre Love Triangle (2002) and contributed the 'Cut' episode to Three...Extremes (2004) - which also contains shorts by Fruit Chan and Takashi Miike - Park completed the triptych with Lady Vengeance (2005), which follows Lee Young-ae as she is released from prison after serving 13 years for the child murder she didn't commit. Her plan to settle old scores with her abusive former teacher (Choi Min-sik) is thrown off, however, when she is reunited with the daughter (Kwon Yae-young) she had given up for adoption. Intriguingly, Park also released a second version of the film, in which the colour gradually fades from the image, which makes for a fascinating comparison with Bong Joon-ho's decision to issue an entirely monochrome version of Parasite.

Changing direction, Park charted the relationship between Im Soo-jung and Jung Ji-hoon (aka Rain) when they meet in a mental institution in I'm a Cyborg (2006). However, he returned to gore with Thirst (2009), a reworking of Émile Zola's Thérèse Raquin that centres on Song Kang-ho, a priest who was turned into a vampire during a failed medical experiment and who finds himself becoming fixated on childhood friend Shin Ha-kyun's young wife, Kim Ok-bin. Having won the Jury Prize at Cannes, Park went to Hollywood to make his English-language bow with Stoker (2013), which pits teenager Mia Wasikowska against Matthew Goode, the uncle she never knew existed, who moves into the family home to console her newly widowed mother, Nicole Kidman.

Park would return to English with a six-part BBC adaptation of John Le Carré's The Little Drummer Girl (2018), in which aspiring actress Florence Pugh's Greek holiday encounter with handsome stranger Alexander Skarsgård delivers her into the clutches of shadowy spymaster Michael Shannon. In between times, Park would rework the 2002 Sarah Waters bestseller, Fingersmith, that Aisling Walsh had already adapted for the BBC, with Elaine Cassidy and Sally Hawkins. In The Handmaiden (2016), the action is transposed from Victorian London to colonial Korea to show how con man Ha Jung-woo installs pickpocket Kim Tae-ri as the maid of Japanese heiress Kim Min-hee as part of his plan to trick her into matrimony.

As the Korean Wave started to capture imaginations beyond the peninsula, critics began employing the term 'well made' to convey the thematic complexity and visual slickness that was shared by features made on markedly different resources. Among the most popular pictures was Kwak Jae-yong's My Sassy Girl (2001), which was remade under the same title in 2008 by Yann Samuell, with Elisha Cuthbert and Jesse Bradford. Equally admired was Kwak Kyung-taek's Friend (2001), which bore the influence of Hong Kong bullet operas, Japanese yakuza movies and Martin Scorsese's made-man sagas to show how childhood pals Yu Oh-seong and Jang Dong-gun become mortal enemies over the course of three decades. Kwak would follow this semi-autobiographical thriller with the boxing biopic, Champion (2002); the mega-budgeted North-South pirate-cum-terrorist actioner, Typhoon (2006); and the epic fact-based Korean War drama, The Battle of Jangsari (2019), which stars Megan Fox as an American photojournalist and which will soon be available to rent from Cinema Paradiso.

Starring Song Kang-ho as a wrestling journeyman who becomes a cult hero, Kim Jee-woon's The Foul King (2000) was more of a domestic than an overseas success. But, having contributed 'Memories' to Three...Extremes 2 (2002), Kim created his masterpiece with A Tale of Two Sisters (2003), a deeply unsettling psychological thriller reworked from an old folktale that has stepmother Yum Jung-ah hearing bumps in the night after meeting new husband Kim Kap-soo's young daughters, Im Soo-jung and Moon Geun-young, who have just emerged from a nursing home after struggling to accept the loss of their mother. Brothers Charles and Thomas Guard cast Elizabeth Banks and David Strathairn in the adult roles opposite Anelle Kebbel and Emily Browning in their 2009 remake, The Uninvited.

Straying from the supernatural, Kim descended into the underworld in A Bittersweet Life (2003), in which hotel manager Lee Byang-hun leads a double life as an enforcer for mobster, Kim Yeong-cheol. However, he has to have his wits about him after he spares the life of Kim's unfaithful mistress, Shin Min-h. Hopping genres again, Kim harked back to the 1930s for The Good, the Bad, the Weird (2008), a kimchi Western that confines train robber Song Kang-ho, bandit Lee Byung-hun and bounty hunter Jung Woo-sung on an express crossing occupied Manchuria, with some Japanese soldiers pursuing both the unholy trio and a valuable map.

Kim Jee-woon changed tack again with I Saw the Devil (2010), a police procedural that sees National Intelligence agent Lee Byung-hun turn his focus on school bus driver Choi Min-sik in his increasingly obsessional quest to unmask the serial killer who had butchered his fiancée. Another lawman discovers the odds stacked against him in Kim's Hollywood debut, The Last Stand (2013), which marked Arnold Schwarzenegger's return to the screen after his decade in gubernatorial politics to play a small-town Arizona sheriff who is gearing up for a showdown with escaped drug baron, Eduardo Noriega. Subsequently, Kim returned to Korea for The Age of Shadows (2015), a gripping colonial thriller that shuttles between Seoul and Shanghai to explore how Korean resistance leader Lee Byong-hun seeks to use antique dealer Gong Yoo to entice police captain Song Kang-ho into betraying his Japanese masters.

For all Park's brutal brilliance and Kim's diversity and dynamism, however, the director Western critics and audiences have taken to their heart is Bong Joon-ho. Why would that be? Perhaps, because having grown up covertly watching Hollywood movies on the American Forces Korea Network, Bong has a surer grasp of what viewers outside Korea want and expect from their big-screen entertainment. But he has also maintained the most consistently high standards since debuting with Barking Dogs Never Bite (2000), an indie variation on the Marie Louise de la Ramée novel that was filmed by James B. Clark as The Dog of Flanders in 1959. In Bong's updating, struggling academic Lee Sung-jae finds himself being suspected by neighbour Bae Doo-na, who is hoping to become famous for investigating the mysterious disappearance from her tenement block of several pets.

Another director who refuses to be confined by genre or auteurial expectation, Bong next turned to Kim Kwang-rim's 1996 fact-based stage play, Come to See Me, for Memories of Murder (2002), a twisting police procedural set in 1986 that follows Seoul cop Kim Sang-kyung to Gyeonggi Province so he can help local officers Song Kang-ho and Kim Roi-ha get to the bottom of a serial killing case that is becoming more impenetrable with each new corpse. Atmospherically photographed by Kim Hyung-koo, this topped the Korean box-office charts until it was surpassed by Kang Woo-suk's Silmido (2003), a tense recreation of the 1968 army bid to assassinate Kim Il-sung that really should be available on disc in this country.

All the Hallyu Wave needed was a monster movie and Bong duly obliged with The Host (2006), which took Korean cinema into CGI territory, thanks to the VFX team behind Frank Miller's Sin City, Mike Newell's Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (both 2005) and Bryan Singer's Superman Returns (2006). At the heart of the bloody mayhem is snack bar owner Song Kang-ho, who joins forces with archery champion sister Bae Doo-na, activist brother Park Hae-il and ageing father Byun Hee-bong to wreak revenge on the monstrous creature that had emerged from the Han River and attempted to snatch Song's daughter, Go Ah-sung.

Pausing to join Leos Carax and Michel Gondry in contributing the 'Shaking Tokyo' vignette to the portmanteau picture, Tokyo! (2008), Bong returned to features with Mother (2009), in which Kim Hye-ja excels as the impoverished acupuncturist who relies on the help of local thug Jin Goo to help her prove that intellectually disabled son Won Bin has been coerced into confessing to the murder of a schoolgirl. Blending suspense, social comment and dark humour, this masterly thriller was followed by another change of tack, as Bong entered the English-language fray with Snowpiercer (2013), an adaptation of a graphic novel by Jacques Lob, Benjamin Legrand and Jean-Marc Rochette that reunited Song Kang-ho and Go Ah-sung as father and daughter aboard a train carrying the last survivors of a calamitous attempt to reverse climate change. Among the other passengers about to be caught up in the class war erupting in the strictly divided compartments are Chris Evans, Tilda Swinton. Ed Harris, John Hurt and Jamie Bell.

Swinton would revel in her villainous role in Okja (2017), in which young Ah Seo-hyun vows to recover the pet super-pig that had been stolen by a sinister corporation. But this Netflix offering was overshadowed by Parasite, which is available from Cinema Paradiso on high quality DVD, Blu-ray and 4K to ensure you see it in all its visual splendour. Once again pairing Bong and Song Kang-ho, the four-time Oscar winner dissects Korean society with a universal insight into human nature, as Song, wife Jang Hye-jin and children Choi Woo-suk and Park So-dam pose as servants to wangle their way into the luxurious household of businessman Lee Sun-kyun and his wife, Cho Yeo-jeong, which has been run like clockwork for years by housekeeper Lee Jung-eun, who has a closely guarded secret lurking in a hidden basement.

Konnoisseur and Kult Korner

While some big name wavers went on to global success, many more had to settle for domestic accolades and the odd bit of cult acclaim. As the veteran Im Kwon-taek was being feted for his 95th feature, Chihwaseon (aka Drunk on Women and Poetry), Lee Chang-dong was winning the Silver Lion at Venice for Oasis (both 2002), a study of how society deals with disability that centres on the relationship between a man with learning difficulties (Sol Kyung-gu) and a woman with cerebral palsy (Moon So-ri). Sadly, Secret Sunshine (2007) isn't available on disc in the UK, but Poetry (2010) should be on any Korean 'must see' list, as renowned actress Yun Yung-hee excels in her first film since 1994 as a sixtysomething with Alzheimer's disease trying to raise her difficult 16 year-old grandson (Lee David).

Adapted from a short story by Haruki Murakami, Burning (2018) would make an offbeat double bill with Jeong Jae-eun's Take Care of My Cat (2001). The first Korean feature to make the shortlist for the Best Foreign Film category at the Academy Award, Lee's most recent outing sees aspiring novelist Yoo Ah-in come to regret agreeing to feed school friend Jun Jong-seo's cat while she's on a trip to Kenya after she introduces him to Steven Yeun, who has a dark secret that could put Jun in danger. Feline fans might also want to check out Byeon Seung-wook's The Cat (2011), a discomfiting chiller in which pet shop groomer Park Min-young is haunted by visions of a murderous cat-eyed girl after inheriting a white Persian named Silky.

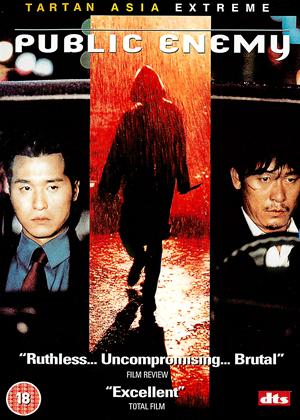

An eerie encounter also lingers in the mind of maverick cop Sol Kyung-gu in Kang Woo-suk's Public Enemy (2002), as he becomes increasingly convinced that the stranger who slashed his face in a dark alley is responsible for a vicious killing spree. Such was the success of the picture that Kang directed a sequel, Another Public Enemy (2005), which sees Sol return as an attorney in the Seoul prosecutor's office who has to resort to unconventional methods when no one believes that much-respected school friend Jung Joon-ho is guilty of embezzlement, bribery and murder.

Kang has devoted much of his subsequent time to Cinema Service, which is one of South Korea's biggest production and distribution companies. But he's not alone in having drifted off the radar since his new wave heyday, as too little has been heard of Park Ki-hyeong since Shim Hye-jin adopted the orphan from hell in Acacia or from Jang Joon-hwan since Shin Ha-kyun became convinced that the boss who has just sacked him is an alien from the Andromeda Galaxy in Save the Green Planet! (both 2003).

Kang Je-kyu also slipped out of the spotlight after following Shiri with Brotherhood (2004), which follows the fortunes of siblings Jang Dong-gu and Won Bin after they are conscripted into the South Korean army in 1950 and dispatched to Inchon during the early days of the Korean War. Despite the film breaking box-office records in being seen by almost 12 million Koreans, Kang didn't direct again until My Way (2011), a Second World War epic that sees bitter enemies Kang Je-gyu and Joe Odagiri become blood brothers as the conflict sweeps them across China, the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe to the Normandy beaches on D-Day.

A Gallic air can also be detected in Untold Scandal (2003), which sees E J-yong (aka Lee Je-Yong) relocate Pierre Choderlos de Laclos's Dangerous Liaisons to 18th-century Korea so that aristocrat Lee Mi-soo can promise to give herself to cousin Bae Yong-jun if he can seduce the innocent Jeon Do-yeon before she becomes her husband's concubine. Sex remains high on the agenda in Dasepo Naughty Girls (2006), although the source of this risqué musical comedy is the webtoon, Multi-Cell Girl. A decade later, Lee anticipated the problems of working during lockdown when he made Behind the Camera (2013) entirely by remote Internet access.

Actress Yun Yeo-jeong was persuaded to participate in Lee's experiment while filming Im Sang-soo's erotic thriller The Taste of Money (2012), She also featured in two of Im's earlier outings, The President's Last Bang (2005), which recreates the events surrounding the 1979 assassination of President Park Chung-hee (Song Jae-ho) by secret service director Kim Jae-kyu (Baek Yoon-sik), and The Housemaid (2010), a remake of Kim K-young's 1960 classic that pairs Yun and Jeon Do-yeon as the servants in the household of the wealthy Lee Jung-jae and his wife, Seo Woo.

Im would also join the likes of Paolo Sorrentino and Nadine Labaki in contributing to the anthology film, Rio, I Love You (2014). But he's another director that UK distributors have rather neglected, as is Hong Sang-soo, a master of offbeat observational comedy who is represented on the Cinema Paradiso slate by the irresistible trio of Woman Is the Future of Man (2004), Tale of Cinema (2005) and Nobody's Daughter Haewon (2013), which all reflect on the transience of romance, the link between life and art and the way people behave under the influence of alcohol.

Scratching the Eight-Year Itch

Although the Korean Wave only officially lasted for eight years between 1997 and 2005, the impact of even overlooked films like Lee Young-jae's The Harmonium in My Memory (2000), Kim Sung-su's Musa: The Warrior, Cho Jin-Gyu's My Wife Is a Gangster (both 2001), Lee Myung-se's Duelist and Park Kwang-hyul's Welcome to Dongmakgol (both 2005) continues to be felt across the board. At the risk of getting a bit listy, you can see what we mean by checking out Korean-American Kim So-yong's Treeless Mountain (2008), Jang Cheol-soo's Bedevilled (2010), documentarist Yi Seung-jun's Planet of Snail (2011), Kim Seong-hoon's A Hard Day, July Jung's A Girl At My Door, Shim Sung-bo's Bong Joon-ho-produced Sea Fog (all 2014), Oh Seung-ook's The Shameless (2015), Jung Byung-gil's The Villainess, Byun Sung-hyun's The Merciless, and Hug Jung's The Mimic (all 2017).

The influence is also evident in genre cinema. There are dozens of South Korean movies on offer at Cinema Paradiso, as you will see if you follow the link in the World Cinema section. Sadly, there isn't room to cover them all, but you know you are in safe hands if you choose from among the titles bearing the following labels: Tartan Asia Extreme: Lim Chang-jae's Unborn But Forgotten, Ahn Byeong-ki's Phone, Jeon Yun-su's Yesterday, Lee Jong-hyuk's H (all 2002), Kim Sung-ho's Into the Mirror, Yun Jae-yeon's Wishing Stairs, Kim Ui-suk's Sword in the Moon (all 2003), Kim Moon-saeng's Sky Blue, Song Il-gon's Spider Forest, Kong Su-chang's R-Point (all 2004), Kim Dae-seung's Blood Rain, Kim Yong-gyun's The Red Shoes, Won Shin-yeon's The Wig, Pang Eun-jin's Princess Aurora, and Lee Woo-cheol's Cello (all 2005); and Terracotta/Third Window: Kim Sang-jin's Kick the Moon, Jin Jang's Guns and Talks, Kim Sung-hong's Say Yes (all 2001), Kim Yoo-jin's Wild Card (2003), Lee Hyong-gon's The Fox Family (2006), Yim Pil-song's Hansel and Gretel (2007), Chang's Death Bell (2008), Yang Ik-joon's Breathless (2009), Owen Cho's Desire to Kill, Yoon Sung-hyun's Bleak Night (both 2010), Shin Su-won's Pluto (2012), Lee Won-suk's How to Use Guys With Secret Tips, Lee Su-jin's Han Gong-Ju, and Song Hae-sung's Boomerang Family (all 2013).

Despite the success that Korean cinema has had worldwide, only its marquee directors have commanded magazine and newspaper articles in Britain. The rest have to make do with fansite profiles. So, Cinema Paradiso would like to point you in the direction of Won Shin-yeom (Bloody Aria, 2006 & The Suspect, 2013), Kim Han-min (War of the Arrows, 2011 & Roaring Currents, 2014) and Park Hoon-jung (New World, 2013 & The Tiger, 2015). And, while you're here, why not discover the work of actor-turned-director Ryoo Seung-wan, who is regarded by some as the Korean Tarantino for the way in which he has rebooted the action genre since debuting with Die Bad (2000) by adding dashes of Jackie Chan and John Woo to neo-noir's like No Blood No Tears (2002), in which aspiring singer Jeon Do-yeon and female gangster Lee Hye-young join forces to steal a duffel bag full of readies.

Ryoo recruited brother Ryoo Seung-bum to headline Arahan (2004), a wuxia comedy that pits a hapless cop and martial arts expert Yoon So-yi against her evil former master (Jung Doo-hong). Ryoo Seung-bum also puts his head in where it hurts in Crying Fist (2005), a true-life Rocky story about how two boxers (the other being played by Choi Min-suk) conquer their demons to succeed in the ring. The mood darkens in The City of Violence (2006), as four childhood friends reunite for the first time in two decades at the funeral of a classmate whose fatal stabbing strikes Seoul cop Jung Doo-hong as decidedly sinister. Since taking an acting role in this gritty drama, Ryoo has focused solely on directing. Three of his most recent four films are not available to rent, but Cinema Paradiso can offer the gripping The Battleship Island (2017), which harks back to 1945 to show how jazz musician Hwang Jung-min and partisan agent Song Joong-ki team to liberate the conscripted labourers in an undersea coal mine.

By contrast, Na Hong-jin has only made three features, but each one has been notable. In The Chaser (2008), disgraced cop Kim Yoon-seok works as a pimp until he's forced to brush up his detecting skills after a number of prostitutes go missing. A vanished wife and some mounting debts prompt gambling cabby Ha Jung-woo to leave his home on border with the North and undertake a contract killing in Seoul in The Yellow Sea (2010), while it's the killing spree that follows the appearance of Japanese stranger Jun Kunimura in a remote southern village that perplexes cop Kwak Do-wan in the unnerving ghost story, The Wailing (2016).

Horror has also become Won Shin-yeom's stock-in-trade, although he made his first impression with The King of Pigs (2011), a caustic animated satire that brings together a wannabe writer and a wife killer to reminisce about their troubled time at a class-conscious school. Won would return to the graphic form for Seoul Station, which formed a prequel to his mega hit, Train to Busan (both 2016), which follows the efforts of workaholic divorcé Gong Yoo to ensure that a zombie apocalypse won't prevent daughter Kim Su-an from celebrating her birthday with her mother. Hilarious and terrifying in equal measure, this wild ride was followed by Peninsula (2020), which takes up the story four years later and accompanies ex-Marine Gang Dong-won returns to Korea to retrieve a lorryload of cash for a Chinese crimelord, only to have his conscience pricked when he encounters a rogue army unit and the woman (Lee Jung-hyun) he had failed to help at the height of the zombageddon.