- General info

- Available formats

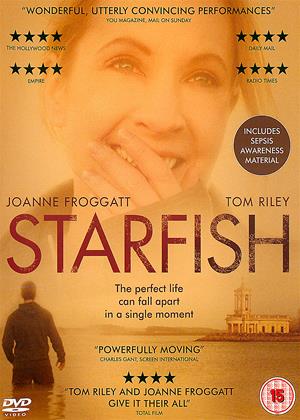

- Synopsis:

- "Starfish" is a remarkable story of survival, based on the true-life story of Tom and Nicola Ray's (Tom Riley and Joanne Froggatt) love, and the survival of that love against all odds. When Tom puts his small daughter to bed one chilly December evening, he has everything a man could want - a beautiful wife and a second baby on the way to complete their perfect family. By the next morning, all is in jeopardy as Tom succumbs to a devastating illness. 'Starfish' is a powerfully honest portrayal of the emotional depths that a family can reach when confronted with the unimaginable.

- Actors:

- Joanne Froggatt, Tom Riley, Phoebe Nicholls, Michele Dotrice, Simon Bamford, Daisy Moore, David Carr, Katie Pattinson, Greg Haiste, Max Krupski, Oliver Cunliffe, Natalie India Balmain, Joey Malone, Isla Crowther, Christopher Howitt, Sophie Bephage, Ellie Copping, Greta West, Elsie Adams, Jonathan Penton

- Directors:

- Bill Clark

- Producers:

- Pippa Cross, Joanne Froggatt, Ros Hubbard, Mel Paton

- Writers:

- Bill Clark

- Studio:

- Spirit Entertainment

- Genres:

- Drama

More like Starfish

Found in these customers lists

Reviews of Starfish

Critic review

Starfish review by Adrijan Arsovski - Cinema Paradiso

Not gonna lie here: Starfish is a film dealing with one of the heaviest subjects ever put to screen (an excruciating illness) which makes this film a tad bit too much to deal with at times (and not for the faint of heart and/or nerves). Are you ready? Here it goes:

Starfish follows double amputee Tom Ray (played by Tom Riley), whose frustrations after his condition are projected on his wife Nicola Ray (Joanne Froggatt) and their relationship is put to the ultimate test. On top of that, Tom is denied any insurance, and so they start to have financial difficulties as well. It seems as if things are desperate for the both of them – given the couple has two small children to care after.

In particular, Tom and Nicola Ray struggle to deal with the excruciating effects of septicaemia. Meanwhile, Tom is a children’s author and so he tells a story about a starfish re-growing its rays to his daughter Grace (Ellie Copping). So, when Tom loses his limbs and a significant part of his lower face during his struggle with sepsis, his daughter pours salt into a water reservoir in hope that her father will be able to regrow his body parts – following the theme of the story. This dramatic scene is both hard to watch and it also reveals the innocence within children with which they try to navigate the world.

Then, the audience witnesses a seemingly idyllic setting, perfectly captured by Clive Norman's camera work, as Tom and Grace bond over flying a kite near Rutland Water. Tom is also plagued by the doctors’ request for Nicola’s consent for his surgery. However, Clark withholds some key information about Tom’s recovery period, which later sends Tom into a downward spiral of resentment and hate. This is Starfish’s melodrama at its finest.

There are few instances in the film where a speech or an idea sits awkwardly and detracts the viewers from delving into the experience fully. I’m mostly referring to the moment when Froggatt delivers a speech about those individuals incapacitated in non-combat activities or other scenarios related to illness or accidents as well. However, the point remains that director Bill Clark manages to drive home the most glaring details in full force, as the real Ray serves as the body double to actor Riley. It’s an extraordinary example of art imitating life imitating art, and Clark’s delivery is all the better for it.

All things considered, Starfish will drain you emotionally and will probably leave an emotional scar you’d have to deal sometimes in the future with. That sole fact gives this film a true gravitas and pathos – something that will make you all but indifferent to it.